По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

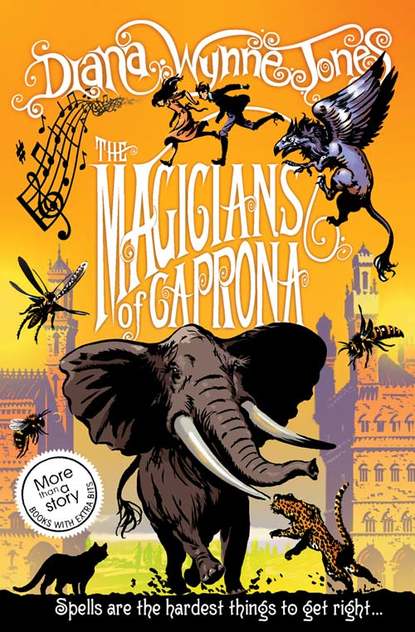

The Magicians of Caprona

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Tonino went to school on Monday, having considered Benvenuto’s advice. And, when the time came when they gave him a picture of a cat and said the shapes under it went: Ker-a-ter, Tonino gathered up his courage and whispered, “Yes. It’s a C and an A and a T. I know how to read.”

His teacher, who was new to Caprona, did not know what to make of him, and called the Headmistress. “Oh,” she was told. “It’s another Montana. I should have warned you. They all know how to read. Most of them know Latin too – they use it a lot in their spells – and some of them know English as well. You’ll find they’re about average with sums, though.”

So Tonino was given a proper book while the other children learnt their letters. It was too easy for him. He finished it in ten minutes and had to be given another. And that was how he discovered about books. To Tonino, reading a book soon became an enchantment above any spell. He could never get enough of it. He ransacked the Casa Montana and the Public Library, and he spent all his pocket money on books. It soon became well known that the best present you could give Tonino was a book – and the best book would be about the unimaginable situation where there were no spells. For Tonino preferred fantasy. In his favourite books, people had wild adventures with no magic to help or hinder them.

Benvenuto thoroughly approved. While Tonino read, he kept still, and a cat could be comfortable sitting on him. Paolo teased Tonino a little about being such a bookworm, but he did not really mind. He knew he could always persuade Tonino to leave his book if he really wanted him.

Antonio was worried. He worried about everything. He was afraid Tonino was not getting enough exercise. But everyone else in the Casa said this was nonsense. They were proud of Tonino. He was as studious as Corinna, they said, and, no doubt, both of them would end up at Caprona University, like Great-Uncle Umberto. The Montanas always had someone at the University. It meant they were not selfishly keeping the Theory of Magic to the family, and it was also very useful to have access to the spells in the University Library.

Despite these hopes for him, Tonino continued to be slow at learning spells and not particularly quick at school. Paolo was twice as quick at both. But as the years went by, both of them accepted it. It did not worry them. What worried them far more was their gradual discovery that things were not altogether well in the Casa Montana, nor in Caprona either.

CHAPTER THREE (#u8bb0f7ee-043a-575e-b2b1-f412da8ddde9)

It was Benvenuto who first worried Tonino. Despite all the care Tonino gave him, he became steadily thinner and more ragged again. Now Benvenuto was roughly the same age as Tonino. Tonino knew that was old for a cat, and at first he assumed that Benvenuto was just feeling his years. Then he noticed that Old Niccolo had taken to looking almost as worried as Antonio, and that Uncle Umberto called on him from the University almost every day. Each time he did, Old Niccolo or Aunt Francesca would ask for Benvenuto and Benvenuto would come back tired out. So he asked Benvenuto what was wrong.

Benvenuto’s reply was that they might let a cat have some peace, even if the Duke was a booby. And he was not going to be pestered by Tonino into the bargain.

Tonino consulted Paolo, and found Paolo worried too. Paolo had been noticing his mother. Her fair hair had lately become several shades paler with all the white in it, and she looked nervous all the time. When Paolo asked Elizabeth what was the matter, she said, “Oh nothing, Paolo – only all this makes it so difficult to find a husband for Rosa.”

Rosa was now eighteen. The entire Casa was busy discussing a husband for her, and there did, now Paolo noticed, seem much more fuss and anxiety about the matter than there had been over Cousin Claudia, three years before. Montanas had to be careful who they married. It stood to reason. They had to marry someone who had some talent at least for spells or music; and it had to be someone the rest of the family liked; and, above all, it had to be someone with no kind of connection with the Petrocchis. But Cousin Claudia had found and married Arturo without all the discussion and worry that was going on over Rosa. Paolo could only suppose the reason was “all this”, whatever Elizabeth had meant by that.

Whatever the reason, argument raged. Anxious Antonio talked of going to England and consulting someone called Chrestomanci about it. “We want a really strong spell-maker for her,” he said. To which Elizabeth replied that Rosa was Italian and should marry an Italian. The rest of the family agreed, except that they said the Italian must be from Caprona. So the question was who.

Paolo, Lucia and Tonino had no doubt. They wanted Rosa to marry their cousin Rinaldo. It seemed to them entirely fitting. Rosa was lovely, Rinaldo handsome, and none of the usual objections could possibly be made. There were two snags, however. The first was that Rinaldo showed no interest in Rosa. He was at present desperately in love with a real English girl – her name was Jane Smith, and Rinaldo had some difficulty pronouncing it – and she had come to copy some of the pictures in the Art Gallery down on the Corso. She was a romantic girl. To please her, Rinaldo had taken to wearing black, with a red scarf at his neck, like a bandit. He was said to be considering growing a bandit moustache too. All of which left him with no time for a cousin he had known all his life.

The other snag was Rosa herself. She had never cared for Rinaldo. And she seemed to be the only person in the Casa who was entirely unconcerned about who she would marry. When the argument raged loudest, she would shake the blonde hair on her shoulders and smile. “To listen to you all,” she said, “anyone would think I have no say in the matter at all. It’s really funny.”

All that autumn, the worry in the Casa Montana grew. Paolo and Tonino asked Aunt Maria what it was all about. Aunt Maria at first said that they were too young to understand. Then, since she had moments when she was as passionate as Aunt Gina or even Aunt Francesca, she told them suddenly and fervently that Caprona was going to the dogs.

“Everything’s going wrong for us,” she said. “Money’s short, tourists don’t come here, and we get weaker every year. Here are Florence, Pisa and Siena all gathering round like vultures, and each year one of them gets a few more square miles of Caprona. If this goes on we shan’t be a State any more. And on top of it all, the harvest failed this year. It’s all the fault of those degenerate Petrocchis, I tell you! Their spells don’t work any more. We Montanas can’t hold Caprona up on our own! And the Petrocchis don’t even try! They just keep turning things out in the same old way, and going from bad to worse. You can see they are, or that child wouldn’t have been able to turn her father green!”

This was disturbing enough. And it seemed to be plain fact. All the years Paolo and Tonino had been at school, they had grown used to hearing that there had been this concession to Florence; that Pisa had demanded that agreement over fishing rights; or that Siena had raised taxes on imports to Caprona. They had grown too used to it to notice. But now it all seemed ominous. And worse shortly followed. News came that the Old Bridge had been seriously cracked by the winter floods.

This news caused the Casa Montana real dismay. For that bridge should have held. If it gave, it meant that the Montana charms in the foundations had given too. Aunt Francesca ran shrieking into the yard. “Those degenerate Petrocchis! They can’t even sustain an old spell now! We’ve been betrayed!”

Though no one else put it quite that way, Aunt Francesca probably spoke for the whole family.

As if that was not enough, Rinaldo set off that evening to visit his English girl, and was led back to the Casa streaming with blood, supported by his cousins Carlo and Giovanni. Rinaldo, using curse words Paolo and Tonino had never heard before, was understood to say he had met some Petrocchis. He had called them degenerate. And it was Aunt Maria’s turn to rush shrieking through the yard, shouting dire things about the Petrocchis. Rinaldo was the apple of Aunt Maria’s eye.

Rinaldo had been bandaged and put to bed, when Antonio and Uncle Lorenzo came back from viewing the damage to the Old Bridge. Both looked very serious. Old Guido Petrocchi himself had been there, with the Duke’s contractor, Mr Andretti. Some very deep charms had given. It was going to take the whole of both families, working in shifts, at least three weeks to mend them.

“We could have used Rinaldo’s help,” Antonio said.

Rinaldo swore that he was well enough to get out of bed and help the next day, but Aunt Maria would not hear of it. Nor would the doctor. So the rest of the family was divided into shifts, and work went on day and night. Paolo, Lucia and Corinna went to the bridge straight from school every day. Tonino did not. He was still too slow to be much use. But from what Paolo told him, he did not think he was missing much. Paolo simply could not keep up with the furious pace of the spells. He was put to running errands, like poor Cousin Domenico. Tonino felt very sympathetic towards Domenico. He was the opposite of his dashing brother Rinaldo in every way, and he could not keep up with the pace of things either.

Work had been going on, often in pouring rain, for nearly a week, when the Duke of Caprona summoned Old Niccolo to speak to him.

Old Niccolo stood in the yard and tore what was left of his hair. Tonino laid down his book (it was called Machines of Death and quite fascinating) and went to see if he could help.

“Ah, Tonino,” said Old Niccolo, looking at him with the face of a grieving baby. “I have gigantic problems. Everyone is needed on the Old Bridge, and that ass Rinaldo is lying in bed, and I have to go before the Duke with some of my family. The Petrocchis have been summoned too. We cannot appear less than they are, after all. Oh why did Rinaldo choose such a time to shout stupid insults?”

Tonino had no idea what to say, so he said, “Shall I get Benvenuto?”

“No, no,” said Old Niccolo, more upset than ever. “The Duchess cannot abide cats. Benvenuto is no use here. I shall have to take those who are no use on the bridge. You shall go, Tonino, and Paolo and Domenico, and I shall take your uncle Umberto to look wise and weighty. Perhaps that way we shan’t look so very thin.”

This was perhaps not the most flattering of invitations, but Tonino and Paolo were delighted nevertheless. They were delighted even though it rained hard the next day, the drilling white rain of winter. The dawn shift came in from the Old Bridge under shiny umbrellas, damp and disgruntled. Instead of resting, they had to turn to and get the party ready for the Palace.

The Montana family coach was dragged from the coach-house to a spot under the gallery, where it was carefully dusted. It was a great black thing with glass windows and monster black wheels. The Montana winged horse was emblazoned in a green shield on its heavy doors. The rain continued to pour down. Paolo, who hated rain as much as the cats did, was glad the coach was real. The horses were not. They were four white cardboard cut-outs of horses, which were kept leaning against the wall of the coach-house. They were an economical idea of Old Niccolo’s father’s. As he said, real horses ate and needed exercise and took up space the family could live in. The coachman was another cardboard cut-out – for much the same reasons – but he was kept inside the coach.

The boys were longing to watch the cardboard figures being brought to life, but they were snatched indoors by their mother. Elizabeth’s hair was soaking from her shift on the bridge and she was yawning until her jaw creaked, but this did not prevent her doing a very thorough scrubbing, combing and dressing job on Paolo and Tonino. By the time they came down into the yard again, each with his hair scraped wet to his head and wearing uncomfortable broad white collars above their stiff Eton jackets, the spell was done. The spell-streamers had been carefully wound into the harness, and the coachman clothed in a paper coat covered with spells on the inside. Four glossy white horses were stamping as they were backed into their traces. The coachman was sitting on the box adjusting his leaf-green hat.

“Splendid!” said Old Niccolo, bustling out. He looked approvingly from the boys to the coach. “Get in, boys. Get in, Domenico. We have to pick up Umberto from the University.”

Tonino said goodbye to Benvenuto and climbed into the coach. It smelt of mould, in spite of the dusting. He was glad his grandfather was so cheerful. In fact everyone seemed to be. The family cheered as the coach rumbled to the gateway, and Old Niccolo smiled and waved back. Perhaps, Tonino thought, something good was going to come from this visit to the Duke, and no one would be so worried after this.

The journey in the coach was splendid. Tonino had never felt so grand before. The coach rumbled and swayed. The hooves of the horses clattered over the cobbles just as if they were real, and people hurried respectfully out of their way. The coachman was as good as spells could make him. Though puddles dimpled along every street, the coach was hardly splashed when they drew up at the University, with loud shouts of “Whoa there!”

Uncle Umberto climbed in, wearing his red and gold Master’s gown, as cheerful as Old Niccolo. “Morning, Tonino,” he said to Paolo. “How’s your cat? Morning,” he said to Domenico. “I hear the Petrocchis beat you up.” Domenico, who would have died sooner than insult even a Petrocchi, went redder than Uncle Umberto’s gown and swallowed noisily. But Uncle Umberto never could remember which younger Montana was which. He was too learned. He looked at Tonino as if he was wondering who he was, and turned to Old Niccolo.

“The Petrocchis are sure to help,” he said. “I had word from Chrestomanci.”

“So did I,” said Old Niccolo, but he sounded dubious.

The coach rumbled down the rainswept Corso and turned out across the New Bridge, where it rumbled even more loudly. Paolo and Tonino stared out of the rainy windows, too excited to speak. Beyond the swollen river, they clopped uphill, where cypresses bent and lashed in front of rich villas, and then among blurred old walls. Finally they rumbled under a great archway and made a crisp turn round the gigantic forecourt of the Palace.

In front of their own coach, another coach, looking like a toy under the huge marble front of the Palace, was just drawing up by the enormous marble porch. This carriage was black too, with crimson shields on its doors, in which ramped black leopards. They were too late to see the people getting out of it, but they gazed with irritated envy at the coach itself and the horses. The horses were black, beautiful slender creatures with arched necks.

“I think they’re real horses,” Paolo whispered to Tonino.

Tonino had no time to answer, because two footmen and a soldier sprang to open the carriage door and usher them down, and Paolo jumped down first. But after him, Old Niccolo and Uncle Umberto were rather slow getting down. Tonino had time to look out of the further window at the Petrocchi carriage moving away. As it turned, he distinctly saw the small crimson flutter of a spell-streamer under the harness of the nearest black horse.

So there! Tonino thought triumphantly. But he rather thought the Petrocchi coachman was real. He was a pale young man with reddish hair which did not match his cherry-coloured livery, and he had an intent, concentrating look as if it was not easy driving those unreal horses. That look was too human for a cardboard man.

When Tonino finally climbed down on Domenico’s nervous heels, he glanced up at their own coachman for comparison. He was efficient and jaunty. He touched a stiff hand to his green hat and stared straight ahead. No, the Petrocchi coachman was real all right, Tonino thought enviously.

Tonino forgot both coachmen as he and Paolo followed the others into the Palace. It was so grand, and so huge. They were taken through vast halls with shiny floors and gilded ceilings, which seemed to go on for miles. On either side of the long walls there were statues, or soldiers, or footmen, adding to the magnificence in rows. They felt so battered by all the grandeur that it was quite a relief when they were shown into a room only about the size of the Casa Montana yard. True, the floor was shiny and the ceiling painted to look like a sky full of wrestling angels, but the walls were hung with quite comfortable red cloth and there was a row of almost plain gilt chairs along each side.

Another party of people was shown into the room at the same time. Domenico took one look at them and turned his eyes instantly on the painted angels of the ceiling. Old Niccolo and Uncle Umberto behaved as if the people were not there at all. Paolo and Tonino tried to do the same, but they found it impossible.

So these were the Petrocchis, they thought, sneaking glances. There were only four of them, to their five. One up to the Montanas. And two of those were children. Clearly the Petrocchis had been as hard-pressed as the Montanas to come before the Duke with a decent party, and they had, in Paolo and Tonino’s opinion, made a bad mistake in leaving one of their family outside with the coach.

They were not impressive. Their University representative was a frail old man, far older than Uncle Umberto, who seemed almost lost in his red and gold gown. The most impressive one was the leader of the party, who must be Old Guido himself. But he was not particularly old, like Old Niccolo, and though he wore the same sort of black frock-coat as Old Niccolo and carried the same sort of shiny hat, it looked odd on Old Guido because he had a bright red beard. His hair was rather long, crinkly and black. And though he stared ahead in a bleak, important way, it was hard to forget that his daughter had once accidentally turned him green.

The two children were both girls. Both had reddish hair. Both had prim, pointed faces. Both wore bright white stockings and severe black dresses and were clearly odious. The main difference between them was that the younger – who seemed about Tonino’s age – had a large bulging forehead, which made her face even primmer than her sister’s. It was possible that one of them was the famous Angelica, who had turned Old Guido green.

The boys stared at them, trying to decide which it might be, until they encountered the prim, derisive stare of the elder girl. It was clear she thought they looked ridiculous. But Paolo and Tonino knew they still looked smart – they felt so uncomfortable – so they took no notice.

After they had waited a while, both parties began to talk quietly among themselves, as if the others were not there. Tonino murmured to Paolo, “Which one is Angelica?”