По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

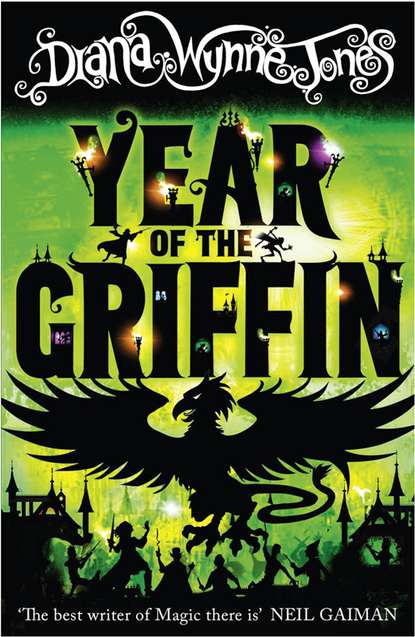

Year of the Griffin

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

They tried not to exchange uneasy looks. Eyes front, Claudia asked, “Why is that?”

“Because it’s not normal,” said the librarian.

“Oh no, of course it isn’t,” Olga said resourcefully. “Corkoran wondered if you’d worry, but he wants us to get into the habit of consulting more than just one book at a time.”

She did not need to nudge Elda for Elda to chime in with “He’s such a lovely tutor. Even his ideas are interesting.”

Elda was so obviously sincere that the librarian shrugged, grumbled, “Oh very well,” and stamped all fifty-four books, with some sighing but no more threats.

They hurried with their volumes to Elda’s concert hall, Ruskin almost invisible under his. Once there, they spread the books out on the floor and got to work examining them for usefulness. Lukin was particularly good at this. He could pick up a book, flip through it and know at once what was in it. Felim did nothing much but sit quivering in a ring of books, as if the books themselves gave him protection. Ruskin was even less useful. He settled himself cross-legged on Elda’s bed with The Red Book of Costamaret open across his knees and turned its pages greedily. He would keep interrupting everyone by reading out things like “To become a wizard, it is needful to think deeper than other men on all things, possible and impossible.”

“Very true. Now shut up,” said Olga. “This one looks very helpful. It’s got lots of diagrams.”

“Put it on this pile then,” said Lukin.

Eventually they had three piles of books. One, a small pile of three, turned out to be almost entirely about raising demons, which they all agreed was not helpful. “My dad raised one once when he was a student,” Elda told them, “and he couldn’t get it to leave. It could be a worse menace than an assassin.”

The other two piles were what Lukin called the offensive and the defensive parts of the campaign, six books on spells of personal protection and thirty-six on magical alarms, traps, deadfalls and trip spells. Claudia knelt between the two piles with her wet-looking curls disordered and her face smudged with dust. “We’ve got roughly three hours until supper,” she said. “I reckon we should get all the protections round him first and then do as many traps as we’ve got time for. How do we start, Lukin?”

“Behold,” boomed Ruskin as Lukin took up the top book from the middle pile, “Behold the paths to the realms beyond. They are all around you and myriad.”

By this time everyone was ignoring Ruskin. “Nearly all of them start with the subject inside a pentagram,” Lukin said, doing his rapid page-flipping. “Some of them have pentagrams chalked on the subject’s forehead, feet and hands too.”

“We’ll do them all,” said Claudia. “Take your shoes off, Felim.”

“What colour pentagrams?” Elda asked, swooping on Felim with a box of chalks.

Lukin turned pages furiously, with Olga leaning over his shoulder. “It varies,” Lukin said. “Green, blue, black, red. Here’s one that says purple.”

“Do one of each colour, Elda,” Claudia instructed.

“Candles,” said Lukin. “That’s constant too. Maximum of twelve candles.” While Olga got up and raced off to the nearest lab for a supply of candles and Elda busily chalked a purple five-sided star on Felim’s forehead, Lukin leafed through all six books again and added, “None of them say what colour the pentagram round the subject should be – just that it must be drawn on the floor.”

“The floor’s all covered with carpet,” Elda objected, drawing a green star on the sole of Felim’s right foot. “Keep still, Felim.”

“You’re tickling!” Felim said.

“Use the top of his foot instead,” Claudia suggested. “Can’t one draw on a carpet with chalk?”

“Yes, but I like my carpet,” said Elda.

“The method of a spell,” Ruskin intoned from the platform, “is not fixed as a law is of nature, but varies as a spirit varies. Consider and think, o mage, and do not do a thing only for the reason it was always done before.”

“Some useful advice for a change,” Elda remarked. She finished drawing on Felim, put the chalks away and arranged the thirty-six books from Lukin’s “offensive” pile into a pentagram around Felim, working with such strong concentration that her narrow golden tongue stuck out from the end of her beak. “There. That saves my nice carpet.”

“The matter of nature,” Ruskin proclaimed, “treated with respect, responds most readily to spells of the body.”

“Oh gods! Is he still at it?” Olga said, returning with a sack of candles from Wermacht’s store cupboard. “Do shut up, Ruskin.”

“Yes, come on down here, Ruskin,” Lukin said, climbing to his feet. “Time to get to work. There are five points to this pattern and five of us apart from Felim, so it stands to reason we’re going to need you.”

Ruskin sighed and pushed The Red Book of Costamaret carefully off his knees. “It’s blissful,” he said. “It’s what I always imagined a book of magic was – until I came here and found Wermacht, I mean. What do we do?”

“Everything out of these six books, I think,” Lukin said. “It ought to be pretty well unbreakable if we do it all, eh, Felim?”

“One would hope,” Felim agreed wanly.

They started with a ring of ninety-nine candles around the pentagram of books, this being all the candles in the sack. Because no one knew how to conjure fire to light them yet, Ruskin lit them all with his flint lighter. Then they stood, one at each point of the pentagram, passing books from hand to hand to talon, reciting rhymes, shouting words of power and attempting to make the gestures in the illustrations. One spell required Elda to hunt out her hand mirror and pass that around too, carefully facing the glass outwards to reflect enemy attacks away from Felim. In between spellings, they all looked anxiously at Felim, but he sat there stoically upright and did not seem to be coming to any harm.

“You will yell if it hurts or anything, won’t you?” each of them said more than once.

“It does not – although I feel rather warm at times,” Felim replied.

So they went doggedly on through all six books. It took slightly less than an hour, because a number of the spells were in more than one book and some, like the mirror spell, were in all six. Nevertheless, by the end they all suddenly found they were exhausted. Elda said the last incantation and sank down on her haunches. The rest simply folded where they stood and sat panting on the carpet.

Here a truly odd thing occurred. All ninety-nine candles burned down at once, sank into puddles of wax on the carpet and flickered out. While Elda was looking sadly at the mess, she saw, out of the end of her left eye, that Felim seemed to be shining. When she whipped her head round to look at him properly, Felim looked quite normal, but when she turned the corner of her other eye towards him, he was shining again, like a young man-shaped lantern, glowing from within. His red sash looked particularly remarkable, and so did his eyes.

Around the pentagram, the others were discovering the same thing. Everyone thought they might be imagining it and no one liked to mention it, until Olga said cautiously, “Does anyone see what I see?”

“Yes,” said Claudia. “My guess is that we’ve discovered witch-sight. Felim, can you see yourself glowing?”

“I have always had witch-sight,” Felim said, “but I hope this effect does not last. I feel like a beacon. May I wash the chalk off now?” But the coloured pentagrams had gone. Felim held out both hands to show everyone.

“It’s worked!” Lukin slapped his own leg in delight. “We did it. We make a good team.”

They were so pleased that much of their tiredness left them. Felim climbed rather stiffly from among the books and they celebrated by eating oranges and the last of the food in the other hamper. Then, still munching, they took up books from the pentagram to find out ways to trap the assassins before they got near Felim.

“My brother Kit would call this overkill,” Elda remarked.

“Overkill is what we’re going for,” said Lukin as he rapidly opened a whole row of books. “Doubled and redoubled safety. Oh-oh. Difficulty. About half these need to be set to particular times. We have to time them for when the assassins actually get here,”

“That’s all right,” Claudia said, peeling her sixth orange. “Oh, Elda, I do love oranges. Even Titus never has this many. We can work out when they’ll get here. Felim, how long did you take on the way?”

Felim smiled. The glow was fading from him, but his confidence seemed to grow as it faded. “Nearly three weeks. But I took a poor horse and devious ways to escape detection. The assassins will travel fast by main roads. Say a week?”

“A week from whenever the letter from the University arrived,” said Claudia. “Elda, when did your father get his?”

“He didn’t say. But,” said Elda, “if it went by one of his clever pigeons, it would take a day to Derkholm and three days to the Emirates.”

“Say the letter was sent the first day of term,” Olga calculated. “Ten days then, three for the pigeon and seven for the assassins. The day after tomorrow is the most likely. But we’ve enough spells here to set them for several nights, starting tomorrow and going on for the next three nights. Agreed?”

“Most for the day after tomorrow, I think,” said Claudia. “Yes.”

Ruskin sprang up. “Let’s get to work then.”

This was something Felim could do too. They took six books apiece and worked through them, each in his or her own way. Felim worked slowly, pausing to give a wide and possibly murderous grin from time to time, and the spells he set up made a lot of use of the knife and fork from Elda’s food hamper. Ruskin went methodically, with strips of orange peel and a good deal of muttering. Once or twice, he dragged The Red Book of Costamaret over and appeared to make use of something it said. Elda and Olga both spent time before they started, choosing the right spells, murmuring things like, “No, I hate slime!” and “Now, that’s clever!” and worked very quickly once they had decided what to do – very different things, to judge from Olga’s heaps of crumbled yellow chalk and Elda’s brisk patterns of orange peel. Lukin worked quickest of all, flipping through book after book, building patterns of crumbs or orange pips, or knotting frayed cloth from Elda’s curtains, or simply whispering words. Claudia was slowest. She seemed to choose what to do by shutting her eyes and then opening a book, after which she would think long and fiercely over the pages, and it would be many minutes before she slowly plucked out one of her own hairs or carefully scraped fluff off the carpet. Once she went outside for a blade of grass, which she burnt with Ruskin’s lighter, before going to the door again and blowing the ash away.

All of them met spells that they could tell were not working. There would be a sort of dragging heaviness, as if the whole universe were resisting what they were trying to do. Nobody let that bother them. If they did enough spells, they were sure some would work. They just went on to a new one. Between them, they set up at least sixty spells. When the refectory bell rang for supper, Elda’s concert hall was littered with peculiar patterns, mingled with books, and all six of them were exhausted.