По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

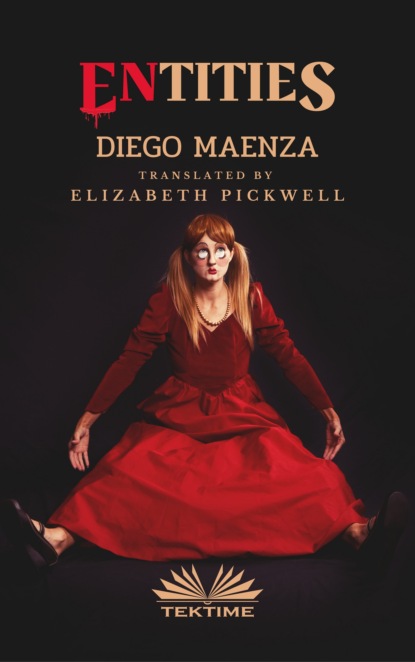

ENtities

Автор

Год написания книги

2021

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

ENtities

Diego Maenza

ENtities is a selection of the five best short stories from BegottEN and the five best stories from IdenTITIES. It includes the following: Family History, The Toad Who Was a Poet, The Cave, The Man in the Mirror, Dawn, The Dream, Inner Monsters (or Fable in One Act), The Night Walk, The Avaricious Man, Ants. “Diego Maenza writes with certainty. Beings and situations that refer us to monsters located in those twisted paths of imagination and reality. These stories are tremendously deep because of the philosophical touches, surprising because of the subject matter and unexpected because of the endings”. (Carlos Ramos, Mexican writer) “His stories convey metaphysical ideas, they play with time and space; they try to make the minimum transcendent, the same nothing. They relocate us, they put us in different territories, they offer us the glances of lonely beings or human beings who must face destinies, even if their missions are not heroic, but only brush against a darkness that can break any spirit ”. (Iván Rodrigo Mendizábal, Ecuadorian writer and critic)

ENtities

Diego Maenza

Translation by Elizabeth Pickwell

Original title in Spanish:

ENtidades

© Diego Maenza, 2021

© Translation by Elizabeth Pickwell

© Tektime, 2021

www.traduzionelibri.it

www.diegomaenza.com

CONTENTS

Family History (#uf7c00e27-3163-5e44-a24b-0860b65f323b)

The Toad Who Was a Poet (#u3618ab85-ccef-5925-89a1-1200f1ce096b)

The Cave (#ueeacf3a7-c316-5bee-b2c9-b6d2766f6420)

The Man in the Mirror (#ua1741764-71c4-57a8-a4ab-99807627a7bc)

Dawn (#u16f0b7c6-a2d8-5f41-8421-d1aec933a6f2)

The Dream (#uf2c7aa30-bb33-59c4-96c4-de92475bc192)

Inner Monsters (or Fable in One Act) (#u8dbb3836-fe22-583f-8864-78f6428c696b)

The Night Walk (#udc653c79-0f19-5a45-ab40-2065fdf37726)

The Avaricious Man (#uba4cfe3a-211c-5db6-9920-372fddc7e27f)

Ants (#u271aad39-5d24-5f61-8d4d-9f967ac78652)

Family History

All my life I have suffered because of my physical appearance. It has been a curse that I have endured since my childhood and so ashamed have I been that I have rarely left my home.

I am afraid that people will look at me. I dread it. It makes me tremble. Some kind doctor once diagnosed me with agoraphobia, but I knew that that mild struggle was a minor tickle compared to my actual condition. I can’t stand people looking at me. I feel stigmatized.

As a result of my deformities, I have become a dishonour to my family which has been the cause of my misfortune and deepest traumas. I must stress: I am the embarrassment of my family. I am the black sheep in my genealogical tree, not because of my actions, but because of the way I am.

To give you an idea, my arms are disproportionate to my body because they are not at the height that would be considered normal. My head is too big. Oh, but my father’s cranial cavity was perfect! It was the pride of his career after becoming a much-recognised public figure in almost the entire nation; women stared and marvelled at him. They went crazy at his presence; the effect he caused within them was almost devastating. I am not exaggerating when I say that upon catching a glimpse of my father as he walked by, they came out in goose bumps, but by hugging their husbands closer and sweet-talking to them, they hid the fact that deep down, they were moaning with pleasure.

I was born with very little hair. Still, my mother loved me. A mother will always love her children, no matter how deformed they are. It infuriates me that I have such a meagre head of hair. My mother’s hair, in contrast, was generous, dense like an untouched jungle, and she showed it off shamelessly every weekend, moving in time to the rhythmic sound of some cabaret music. She always won the sincere applause of the masculine half of the audience who were hypnotised by her sensual movements. The little hair I have, on the other hand, is dull. And it pains me not to have inherited my mother’s beautiful hair.

I never knew my grandmother, but my mother always told me that she had a special, loving, and hypnotic look. As if telling me some forbidden legend, she whispered secretly to me that there was no man who could resist her imposing gaze. About my grandfather, however, she would tell me fascinating stories out loud of the artisan wonders he made with his fantastical arms. He was a fully-fledged artist.

Sometimes I fell in love, several times with two girls at the same time, but my distorted attempts at showing it were never picked up, and so I concluded that those beautiful girls never noticed me because of my disfigurement. I have uncles and cousins who were born with their organs in the correct position. None of them with my shortcomings.

I look at the family album with nostalgia and pride. There was a photo of my father in the Birdmink circus, with a beautiful tiny head devoid of hair, except for a few fine golden strands adorning his microcephalus like a rising sun and with his albino, new-born eyelashes. A little less and he would have been born completely bald, handsome like no other. The photo of my mother showed her with skin covered in brown hair, her downy neck like a matriarchal lioness and her woolly arms like an Angora rabbit. The photographer captured her at her best, most radiant, when her body hair covered her entire anatomy, and nobody was allowed to overshadow her luminous show nights as a werewolf. I was captivated by the photo of my grandfather. If he were alive today, he would hug me with his six-inch upper limbs and his minuscule fingers which had transformed into crippled stumps. And I know that he would hug me, despite feeling embarrassed at the thought of my perfectly proportioned arms. My grandmother, with her one eye in the middle of her forehead, would have shed a stream of tears if she had met me at birth, when she noticed my two perfectly aligned hazel-coloured eyes. But my mother would have always loved me, despite me having this horrible smooth skin.

I was born like that, deformed, and they will never know the shame I feel. When my parents died and I was fifteen, the elephant man and the bearded woman exiled me from the circus, claiming that there was nothing special about me. They said that I did not possess any particular characteristic to justify my staying with them, because as I grew older, I looked more and more like a common spectator. When I was expelled from the big top, I resigned myself to the realisation that I would never conquer the double heart of the Siamese twins. That certainty is the most unpleasant part of my condition. Yes, I am a freak and it’s exhausting. It is a curse that I must bear until the last of my days.

The Toad Who Was a Poet

and yet I love you toad,

how that woman from Lesbos loved the early roses

but more and your smell is more beautiful because I can smell you

Juan Gelman, Lament for the toad by stanley hook

It was never a secret to anyone, that from a very young age, Toad loved to frequent the ponds. When he was just an infant, Toad discovered an indescribable pleasure in being splattered with mud. It was something that made him feel unique, special, different, empowered, especially considering that the mothers of the other boys did not allow their offspring to bathe in the filth of the swampy pools. So, when Toad returned home from the swamps, smeared with dried mud and the remains of water lilies on his only overalls, in the sight of his pubescent friends, he was like an anonymous hero returning from his fight against the incarnation of evil. The boys had a secret admiration for him. The same could not be said for their mothers, for whom Toad represented the personification of filth and neglect. They were disgusted and fearful, feelings disguised, of course, as a supposed look of pity.

In spite of everything, the boys were always attentive to him, and when they noticed that Toad was prowling around with the intention of joining in with their games, the boys, counting on his friendship, revelled in the commotion he brought to the group. This way, the next day they would have a very important topic of conversation at the school gates. They threw the ball at him, and as always, Toad stopped it with his robust vocal sac that forced him to emit a loud and healthy croak.

In ball games, Toad was always the goalkeeper, as his powerful legs allowed him to give the necessary momentum to guide his heavy body towards the ball and stop it with his webbed fingers. Toad would then adopt a smile of complacency and happiness and the boys would reward him with some slimy insects that they secretly collected for him with patience and love.

Oh, how beautiful life was! At least it was until the mothers of the neighbourhood poked their dishevelled heads out of the windows of each house. While some were washing the dishes, others were washing clothes, and they called the names of their children so that they would come home. And obviously, so that they distanced themselves from the dangerous presence of Toad who could spread, they claimed while scolding their children inside their homes, diseases such as red-leg syndrome, chytridiomycosis, neoplasms, papillomas or salmonellosis. So, Toad was left alone, and with a hop and a jump, he would go to the only refuge that allowed him to escape the tangible reality of life: the swamp.

In the midst of this loneliness, Toad roamed the vast swamps for weeks; on other occasions, he travelled to every corner of the mud flats and came out feeling much better. But what really opened his eyes was spending time at what he began to call the poetic quagmire. Here, several of his fellow toads gathered to sing together at night, sometimes in a choir and sometimes as a solo which was always such a mystical and solemn sight. Even though Toad learned with humility, he carried within himself a stubborn pride and self-belief that he was born with a virtue that no one, not even the most crystalline purity of some enchanted lagoon, could erase. He was convinced that he was the bearer of the gift of poetry, and that his inner knowledge transcended the increasingly insipid choir recitals sung by those common frogs.

If as a young boy Toad was a problem for the boys’ mothers, after puberty, the young and handsome Toad became a complication for the girls' mothers too. It's not that the mothers didn’t like him for who he was; on the contrary, his charm secretly attracted even the most prim and proper mothers who really should be the ones trying to demonstrate modesty and set a good example for their daughters. The real reason they despised Toad was because he was a poet. Because according to the upright ladies of the most honourable households, he was a good-for-nothing toad. “What will you live on, my daughter, if all he knows is how to hang out at the swamps?” they said.

But it is common knowledge that in the young girls’ eyes, their parents’ advice always seems so over the top, boring, old-fashioned, unnecessary and over-bearing. So much so that their advice ends up like water off a duck’s back. And all the while, the girls are attracted to that enigmatic spark of mystery that extraordinary beings, especially poet toads, usually emit. The girls began to go crazy, yearning for Toad to invite them just once on a date to the swamp, or invite them to join him as he leapt from water lily to water lily. There were frequent squabbles that often reached the extreme of scratches, hair pulling and, of course, broken noses.

Toad reacted indifferently to all these events, since his life was fully devoted to poetry. During this time, existential thoughts began to incubate within Toad. Sitting on a stone in the swamp, at a particularly warm time of year, anyone who would have looked up to the constellations in the east would have observed the unmistakeable sign of Toad reflected in the stars. But leaving aside the esoteric connotations that such a situation may carry, for our character in question, that elusive and vaguely recognisable figure in the sky had no other significance than the brevity of life itself. A star, Toad thought, is far superior than any living being who could look up at it, having formed at the beginning of the universe.

The most radical beings, who in matters of a practical nature, always stand out as the most sensible, will say that Toad is far too pessimistic. Nevertheless, there will be others who, leaving aside the customary trends of the times, will recognise the value of the depth and clarity in young Toad’s words. But let's get to the point: he never shared his thoughts with anyone, nor did he put them in writing. Incidentally, they aren’t really worth analysing from a philosophical point of view. We all know that philosophers are such tormented beings who are visited only by fatality and apathy and who have never been distracted by the succulent aroma of women. Such is the case with this pensive Toad who is habitually consumed by this bittersweet torment of poets.

It is true that he had never met a poet in person and he recognised it with pride, since he always strongly believed that bathing in the poets’ pools was a much more tormenting and profound process than the hypothetical, but not impossible opportunity to get to know their souls through reading their work instead. What our Toad did not realise is that both things could very well be the same.

We could say that the idea that Toad had in reference to poetry was beautiful but absurd. But actually, it wasn’t like that, since Toad, who at that moment was stretching his hindquarters, getting up from the stone that served as a lookout point at the tip of the headland, never wrote a poem down on paper.

You could say that he performed them. He kept them stored in his memory for the days he needed them most, as if to feed his life and dreams, injecting into his soul one more breath of hope, to keep holding on to the tightrope of his life. All this to then discard them like the many tissues used and thrown away amid a terrible cold.

Diego Maenza

ENtities is a selection of the five best short stories from BegottEN and the five best stories from IdenTITIES. It includes the following: Family History, The Toad Who Was a Poet, The Cave, The Man in the Mirror, Dawn, The Dream, Inner Monsters (or Fable in One Act), The Night Walk, The Avaricious Man, Ants. “Diego Maenza writes with certainty. Beings and situations that refer us to monsters located in those twisted paths of imagination and reality. These stories are tremendously deep because of the philosophical touches, surprising because of the subject matter and unexpected because of the endings”. (Carlos Ramos, Mexican writer) “His stories convey metaphysical ideas, they play with time and space; they try to make the minimum transcendent, the same nothing. They relocate us, they put us in different territories, they offer us the glances of lonely beings or human beings who must face destinies, even if their missions are not heroic, but only brush against a darkness that can break any spirit ”. (Iván Rodrigo Mendizábal, Ecuadorian writer and critic)

ENtities

Diego Maenza

Translation by Elizabeth Pickwell

Original title in Spanish:

ENtidades

© Diego Maenza, 2021

© Translation by Elizabeth Pickwell

© Tektime, 2021

www.traduzionelibri.it

www.diegomaenza.com

CONTENTS

Family History (#uf7c00e27-3163-5e44-a24b-0860b65f323b)

The Toad Who Was a Poet (#u3618ab85-ccef-5925-89a1-1200f1ce096b)

The Cave (#ueeacf3a7-c316-5bee-b2c9-b6d2766f6420)

The Man in the Mirror (#ua1741764-71c4-57a8-a4ab-99807627a7bc)

Dawn (#u16f0b7c6-a2d8-5f41-8421-d1aec933a6f2)

The Dream (#uf2c7aa30-bb33-59c4-96c4-de92475bc192)

Inner Monsters (or Fable in One Act) (#u8dbb3836-fe22-583f-8864-78f6428c696b)

The Night Walk (#udc653c79-0f19-5a45-ab40-2065fdf37726)

The Avaricious Man (#uba4cfe3a-211c-5db6-9920-372fddc7e27f)

Ants (#u271aad39-5d24-5f61-8d4d-9f967ac78652)

Family History

All my life I have suffered because of my physical appearance. It has been a curse that I have endured since my childhood and so ashamed have I been that I have rarely left my home.

I am afraid that people will look at me. I dread it. It makes me tremble. Some kind doctor once diagnosed me with agoraphobia, but I knew that that mild struggle was a minor tickle compared to my actual condition. I can’t stand people looking at me. I feel stigmatized.

As a result of my deformities, I have become a dishonour to my family which has been the cause of my misfortune and deepest traumas. I must stress: I am the embarrassment of my family. I am the black sheep in my genealogical tree, not because of my actions, but because of the way I am.

To give you an idea, my arms are disproportionate to my body because they are not at the height that would be considered normal. My head is too big. Oh, but my father’s cranial cavity was perfect! It was the pride of his career after becoming a much-recognised public figure in almost the entire nation; women stared and marvelled at him. They went crazy at his presence; the effect he caused within them was almost devastating. I am not exaggerating when I say that upon catching a glimpse of my father as he walked by, they came out in goose bumps, but by hugging their husbands closer and sweet-talking to them, they hid the fact that deep down, they were moaning with pleasure.

I was born with very little hair. Still, my mother loved me. A mother will always love her children, no matter how deformed they are. It infuriates me that I have such a meagre head of hair. My mother’s hair, in contrast, was generous, dense like an untouched jungle, and she showed it off shamelessly every weekend, moving in time to the rhythmic sound of some cabaret music. She always won the sincere applause of the masculine half of the audience who were hypnotised by her sensual movements. The little hair I have, on the other hand, is dull. And it pains me not to have inherited my mother’s beautiful hair.

I never knew my grandmother, but my mother always told me that she had a special, loving, and hypnotic look. As if telling me some forbidden legend, she whispered secretly to me that there was no man who could resist her imposing gaze. About my grandfather, however, she would tell me fascinating stories out loud of the artisan wonders he made with his fantastical arms. He was a fully-fledged artist.

Sometimes I fell in love, several times with two girls at the same time, but my distorted attempts at showing it were never picked up, and so I concluded that those beautiful girls never noticed me because of my disfigurement. I have uncles and cousins who were born with their organs in the correct position. None of them with my shortcomings.

I look at the family album with nostalgia and pride. There was a photo of my father in the Birdmink circus, with a beautiful tiny head devoid of hair, except for a few fine golden strands adorning his microcephalus like a rising sun and with his albino, new-born eyelashes. A little less and he would have been born completely bald, handsome like no other. The photo of my mother showed her with skin covered in brown hair, her downy neck like a matriarchal lioness and her woolly arms like an Angora rabbit. The photographer captured her at her best, most radiant, when her body hair covered her entire anatomy, and nobody was allowed to overshadow her luminous show nights as a werewolf. I was captivated by the photo of my grandfather. If he were alive today, he would hug me with his six-inch upper limbs and his minuscule fingers which had transformed into crippled stumps. And I know that he would hug me, despite feeling embarrassed at the thought of my perfectly proportioned arms. My grandmother, with her one eye in the middle of her forehead, would have shed a stream of tears if she had met me at birth, when she noticed my two perfectly aligned hazel-coloured eyes. But my mother would have always loved me, despite me having this horrible smooth skin.

I was born like that, deformed, and they will never know the shame I feel. When my parents died and I was fifteen, the elephant man and the bearded woman exiled me from the circus, claiming that there was nothing special about me. They said that I did not possess any particular characteristic to justify my staying with them, because as I grew older, I looked more and more like a common spectator. When I was expelled from the big top, I resigned myself to the realisation that I would never conquer the double heart of the Siamese twins. That certainty is the most unpleasant part of my condition. Yes, I am a freak and it’s exhausting. It is a curse that I must bear until the last of my days.

The Toad Who Was a Poet

and yet I love you toad,

how that woman from Lesbos loved the early roses

but more and your smell is more beautiful because I can smell you

Juan Gelman, Lament for the toad by stanley hook

It was never a secret to anyone, that from a very young age, Toad loved to frequent the ponds. When he was just an infant, Toad discovered an indescribable pleasure in being splattered with mud. It was something that made him feel unique, special, different, empowered, especially considering that the mothers of the other boys did not allow their offspring to bathe in the filth of the swampy pools. So, when Toad returned home from the swamps, smeared with dried mud and the remains of water lilies on his only overalls, in the sight of his pubescent friends, he was like an anonymous hero returning from his fight against the incarnation of evil. The boys had a secret admiration for him. The same could not be said for their mothers, for whom Toad represented the personification of filth and neglect. They were disgusted and fearful, feelings disguised, of course, as a supposed look of pity.

In spite of everything, the boys were always attentive to him, and when they noticed that Toad was prowling around with the intention of joining in with their games, the boys, counting on his friendship, revelled in the commotion he brought to the group. This way, the next day they would have a very important topic of conversation at the school gates. They threw the ball at him, and as always, Toad stopped it with his robust vocal sac that forced him to emit a loud and healthy croak.

In ball games, Toad was always the goalkeeper, as his powerful legs allowed him to give the necessary momentum to guide his heavy body towards the ball and stop it with his webbed fingers. Toad would then adopt a smile of complacency and happiness and the boys would reward him with some slimy insects that they secretly collected for him with patience and love.

Oh, how beautiful life was! At least it was until the mothers of the neighbourhood poked their dishevelled heads out of the windows of each house. While some were washing the dishes, others were washing clothes, and they called the names of their children so that they would come home. And obviously, so that they distanced themselves from the dangerous presence of Toad who could spread, they claimed while scolding their children inside their homes, diseases such as red-leg syndrome, chytridiomycosis, neoplasms, papillomas or salmonellosis. So, Toad was left alone, and with a hop and a jump, he would go to the only refuge that allowed him to escape the tangible reality of life: the swamp.

In the midst of this loneliness, Toad roamed the vast swamps for weeks; on other occasions, he travelled to every corner of the mud flats and came out feeling much better. But what really opened his eyes was spending time at what he began to call the poetic quagmire. Here, several of his fellow toads gathered to sing together at night, sometimes in a choir and sometimes as a solo which was always such a mystical and solemn sight. Even though Toad learned with humility, he carried within himself a stubborn pride and self-belief that he was born with a virtue that no one, not even the most crystalline purity of some enchanted lagoon, could erase. He was convinced that he was the bearer of the gift of poetry, and that his inner knowledge transcended the increasingly insipid choir recitals sung by those common frogs.

If as a young boy Toad was a problem for the boys’ mothers, after puberty, the young and handsome Toad became a complication for the girls' mothers too. It's not that the mothers didn’t like him for who he was; on the contrary, his charm secretly attracted even the most prim and proper mothers who really should be the ones trying to demonstrate modesty and set a good example for their daughters. The real reason they despised Toad was because he was a poet. Because according to the upright ladies of the most honourable households, he was a good-for-nothing toad. “What will you live on, my daughter, if all he knows is how to hang out at the swamps?” they said.

But it is common knowledge that in the young girls’ eyes, their parents’ advice always seems so over the top, boring, old-fashioned, unnecessary and over-bearing. So much so that their advice ends up like water off a duck’s back. And all the while, the girls are attracted to that enigmatic spark of mystery that extraordinary beings, especially poet toads, usually emit. The girls began to go crazy, yearning for Toad to invite them just once on a date to the swamp, or invite them to join him as he leapt from water lily to water lily. There were frequent squabbles that often reached the extreme of scratches, hair pulling and, of course, broken noses.

Toad reacted indifferently to all these events, since his life was fully devoted to poetry. During this time, existential thoughts began to incubate within Toad. Sitting on a stone in the swamp, at a particularly warm time of year, anyone who would have looked up to the constellations in the east would have observed the unmistakeable sign of Toad reflected in the stars. But leaving aside the esoteric connotations that such a situation may carry, for our character in question, that elusive and vaguely recognisable figure in the sky had no other significance than the brevity of life itself. A star, Toad thought, is far superior than any living being who could look up at it, having formed at the beginning of the universe.

The most radical beings, who in matters of a practical nature, always stand out as the most sensible, will say that Toad is far too pessimistic. Nevertheless, there will be others who, leaving aside the customary trends of the times, will recognise the value of the depth and clarity in young Toad’s words. But let's get to the point: he never shared his thoughts with anyone, nor did he put them in writing. Incidentally, they aren’t really worth analysing from a philosophical point of view. We all know that philosophers are such tormented beings who are visited only by fatality and apathy and who have never been distracted by the succulent aroma of women. Such is the case with this pensive Toad who is habitually consumed by this bittersweet torment of poets.

It is true that he had never met a poet in person and he recognised it with pride, since he always strongly believed that bathing in the poets’ pools was a much more tormenting and profound process than the hypothetical, but not impossible opportunity to get to know their souls through reading their work instead. What our Toad did not realise is that both things could very well be the same.

We could say that the idea that Toad had in reference to poetry was beautiful but absurd. But actually, it wasn’t like that, since Toad, who at that moment was stretching his hindquarters, getting up from the stone that served as a lookout point at the tip of the headland, never wrote a poem down on paper.

You could say that he performed them. He kept them stored in his memory for the days he needed them most, as if to feed his life and dreams, injecting into his soul one more breath of hope, to keep holding on to the tightrope of his life. All this to then discard them like the many tissues used and thrown away amid a terrible cold.