По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

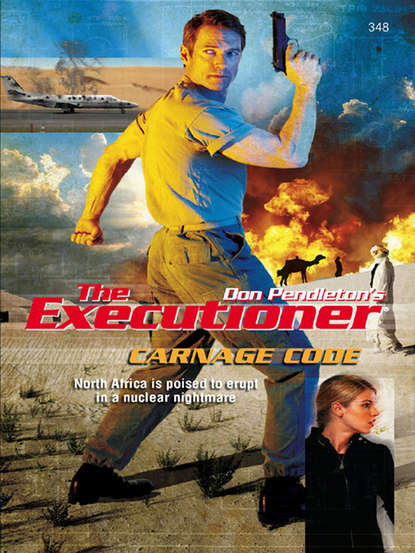

Carnage Code

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Instead, he’d been told that there was a “plainclothes Marine” who might be willing to talk to him.

That was when he’d met that son of a bitch Bill Sims.

Sims, he had quickly surmised after being led into one of the rear offices, was actually CIA. At least his stiff-necked attitude reminded Cassetti of all the spook supervisors he’d seen in a million movies. Maybe that was the way CIA operatives really acted. Or maybe Sims had just seen the same movies and believed that was how he was supposed to act.

Life was either imitating art or art was imitating life. Cassetti didn’t know which, and didn’t really care. He just wanted to be out of this cage and as far away from Sudan as possible.

Cassetti remembered that he had sat across the desk while Sims looked at the sheet of paper inside the envelope. And while the agent had done his best to keep his face deadpan, it was obvious that the limerick was having some kind of effect on him. But it was also evident that Sims didn’t fully understand what the words meant any more than Cassetti did.

The young journalist shifted uncomfortably on the steel ledge. The first thing Sims had done was looked at his passport, then gotten his home address and Social Security number from him. Then he’d made a call to Langley, where a background check on Cassetti would be conducted.

“Simply routine,” Sims had said. “You can understand. We have to weed out the nuts somehow. Not that I think you’re crazy—but it’s procedure.”

At this point, Cassetti had still been nodding and cooperating.

But before he and Sims had a chance to speak about the limerick, the CIA man’s phone had rung. He’d picked it up, listened for a moment, then said, “They have them in custody now?”

Then he’d hung up, looked at Cassetti and said, “You’re a good and patriotic American, son. Now, suppose we take a little ride together. The Sudanese cops have just picked up the two men who killed the old man and they need you to identify them.”

Cassetti’s mistake had been trusting Sims. On the ride to the SNP’s central station, the CIA man’s cell phone had rung and he’d done more listening than talking. The next thing the young American knew, he was at the headquarters of the Sudan National Police and in this jail cell sitting on the steel sleeping platform. And he still didn’t know what the hell was going on.

He had evidently stumbled onto something big, and for all he knew, the next trip he took might be out into the desert where Sims, or some Sudanese cop, would put a bullet in the back of his head.

Cassetti’s thoughts returned to the present as he heard two sets of footsteps coming down the run outside his cell.

“As I said, we booked him in as a material witness,” a heavily accented Sudanese voice said in English, “because we had no assurance he would not flee the country. Not to mention the fact that the men who killed the old man would probably find him and kill him, too. “

An American voice answered, but Cassetti could not make out the words.

“That, too,” the Sudanese said. “I find it funny that he is right down the hall from the two murderers, and they do not even know it.”

“I find it even funnier that they’re employees of your government and claim they were just following orders,” the American answered, still out of sight.

“Yes,” the Sudanese said. “I will check into that. But I will have to be very discreet.”

Now the two men came into view, stopping in front of Cassetti’s cell. It was easy to tell which was which. The uniformed man with the nearly bald head was built like a brick wall. But the American, taller and even broader in the shoulders, looked to be even more powerful.

Ronnie Cassetti wasn’t too sure his martial-arts expertise was going to work on either one of them.

The Sudanese man produced a huge key ring from somewhere behind his back and jammed one of the keys into the door. “Come on,” he said to Cassetti. “You’re being sprung, as you Americans say.”

“For what?” Cassetti answered, not moving. “So this big son of a bitch can kill me? He CIA, too?”

It looked as if the big American was trying not to laugh. The he said, “No, son, it’s because I need your help.”

“I’ve already given you all the help I can give anybody,” Cassetti said, not moving from the sleeping ledge. “I gave Sims the limerick.”

“Yes, but Sims is off the case now and I’m on it. And as I understand it, you’ve studied English literature.”

“How did you know that?” Cassetti asked.

“We may be a rather backward country with limited resources—” the Sudanese cop laughed “—but we have a rather good relationship with the local CIA. Mr. Sims checked into your background and shared that information with us. Your full name is Ronald Delbert Cassetti. You were born in Enid, Oklahoma. Until a few short weeks ago you were a college student at Georgetown. Then, through a friend, you lucked into a job with the Washington Post. ”

“You’ll have to excuse me,” Cassetti said with as much sarcasm as he could put into his tone of voice. “if I don’t exactly consider the Post job as a stroke of luck at the moment.” He pulled his feet up under him and sat cross-legged on the steel bench.

“The most interesting thing the CIA learned,” the big American added, “is that you’re quite a ladies’ man. But right now you’ve found your butt caught in a crack. You’ve fallen in love with a woman while your steady girlfriend is out of town and you’re trying to decide what to do when she gets back.” He paused, looked at his watch and Cassetti figured he must be checking the date, then finished with, “And you don’t have much time left to make that decision.”

“Dammit!” Cassetti yelled, uncrossing his legs and jumping to his feet. “That’s none of your damn business. You spook bastards ever heard of the right of privacy?”

Now the big man did laugh. “First off,” he said, “if by spook you mean CIA, I’ve already told you I’m not a spook. Second, whether or not I’m a bastard depends on which side of right and wrong you stand. But third, yes, the CIA does know about the right to privacy. They just don’t always pay a lot of attention to it when the safety of America, and sometimes the world, is at stake.”

Cassetti walked forward, ready to punch the big man out even if he got his own ass kicked in the process. “You are too with the CIA, you liar,” he said, clenching his fists.

“No, I told you I’m not, and I meant it. Just that they did run an investigation on you, which included your private life, and part of what they learned was about your problem with women.”

He had barely gotten the words out of his mouth when Cassetti lunged forward and snapped a fist at his face. A second later, the young man found that his arm had been blocked, caught, twisted behind his back, and that the big man had reached up with his other hand and grasped him by the hair.

“That’s not something you really want to try again, is it?” the big American asked.

Cassetti felt as if his shoulder was about to come out of the socket as his arm was pushed up and his head pulled down. He knew this technique. In fact, he taught it. But he had never seen it performed with the speed or fluidity this big American had just demonstrated.

“I guess not,” Ronnie Cassetti grunted.

The big man dropped his arm and hair and stepped back. “Then let’s go, kid,” he said. “We’ve got work to do.”

Cassetti turned to face the man. “What do I call you?”

“Brandon or Stone will do.”

“All right, then,” Cassetti said. “Brandon or Stone. I’ll come with you and I’ll help you. But I’ve got one demand.”

“You are not in any position to make demands,” the Sudanese police officer warned.

“Go ahead,” Bolan said. “Let’s hear it.’

“You call me Ron. My name’s not kid. ”

Bolan’s face was serious as he nodded. “All right, then, Ron,” he said. “Let’s go. Like I said, we’ve got work to do.”

B Y NOW , B OLAN KNEW the layout of the Sudan National Police headquarters building almost as well as Urgoma. So he led the way down the hall, with the colonel and Ron Cassetti close at his heels. He had already formed a quick impression of the young American journalist, and as was the case with most human beings, it contained both positive and negative aspects.

On the negative side, Cassetti was inexperienced, short-tempered and impatient. He was also royally pissed off that the CIA had pried into his private love life, and for that the Executioner wasn’t sure he could blame him.

Bolan continued to think about the young man as they neared the locked door where the two blood-soaked hit men still waited. Cassetti had some positive attributes, too. First, the same lack of age that made him somewhat immature gave him energy, and the Executioner knew a lot of energy was going to be expended before he got to the bottom of what was happening in Sudan. And Bolan sensed that even though he certainly had a tendency to lie to women—at his age, a young man often did more thinking with his hormones than brain cells—deep down, Ron Cassetti was an honest man.

Nor could the Executioner discount the kid’s education in writing and literature. To decipher the limerick, an in-depth understanding such as Cassetti’s might prove vital.

Bolan had intended to walk on past the door behind which the Sudanese Department of Defense men sat. He might find it useful to talk to them again later but for now he had learned all he could. Besides, they weren’t going anywhere.