По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

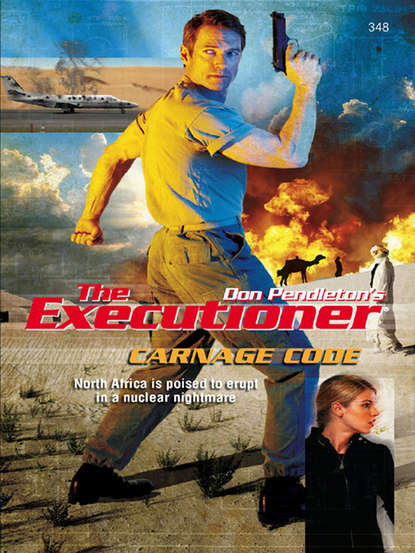

Carnage Code

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“We made quite a stir out at the airport when I arrived,” the Executioner said. “My pilot and I got attacked by a bunch of those guys they’re calling greenies.”

“Yeah,” Cassetti said, “I heard about it. Lots of guns, bullets and dead green bodies. And I don’t mean dead little green spacemen.”

Bolan ignored the comment as irrelevant. Much of what Cassetti said, he had learned during the short few hours he’d known the young man, fell into that category. “In any case, I was seen. And there’s a good chance some of the bad guys in this mess have seen you around town during the last few days, too. We need to change our appearances.”

“Okay,” Cassetti said. “That’s one thing. You said a ‘couple’, which means two. What’s the other thing?”

“We need different wheels,” Bolan said as he started down the street. “Wheels whose licence plate doesn’t check back to the Sudan National Police.”

“I remember you telling Urgoma you’d take care of that yourself,” Cassetti said. “You don’t trust him?”

The Executioner shrugged. “I trust him as much as anybody I’ve met so far in Sudan. But it’s still early in the game. At this point, I can’t afford to trust anybody. ”

Out of the corner of his eye, Bolan saw Cassetti frown. “Does that include me?” he asked, sounding insulted.

Bolan let a low chuckle escape his lips. “I trust your honesty,” he said. “Maybe not with women, but with matters of U.S. security you seem trustworthy enough.” He cleared his throat, paused a moment, then said, “Look, Ron. I’m not trying to be hard on you. But I don’t think you quite understand the situation.” Guiding the SNP car toward the airport, he went on. “The way I see it, is that we’ve got three enemies—the Ethiopian regular army troops crossing the border, the CUD rebels doing the same thing and this rogue element within the Sudan government. And that means we’re more than likely going to confront a whole lot of men, far more experienced than you, who won’t think any more about blowing your head off than they would stepping on a centipede.”

“I saw that back at the police station,” Cassetti said. “I watched two men die agonizing deaths far worse than getting their heads blown off.”

The Executioner found a parking spot in the lot behind the main terminal and pulled into it. “Yes,” he said. “You did. And you looked a little green around the gills.” Killing the engine, he turned back to face the young man again. “When it hits the fan, Ron, am I going to be able to count on you helping me out, or am I going to have to play babysitter?”

The conviction in the young man’s eye might have been real. Then again, it could have just been an act. “You can count on me,” he said firmly.

“Let’s hope so,” Bolan replied as he opened the door and got out. He heard Cassetti do the same on the other side of the vehicle. “So now we do three things here.’

“What are they?” the young man asked.

“Check with my pilot on how the repairs are going on our plane. It got shot up pretty badly when we landed.” He started across the lot toward the rear of the terminal, Cassetti at his side. “Then we get a rental car to drive that won’t check back to the cops.”

“And…” Cassetti’s voice trailed off.

“We get some firepower for you,” the Executioner said. “There’s plenty of equipment to choose from onboard the Learjet.”

“I S IT TRUE BLONDES HAVE more fun?” Ronnie Cassetti asked in a humorous tone from his seat on the bed in room 307 of the Hotel Nubian.

Bolan stood just inside the bathroom, drying his hair with a towel. Hanging it back on the rack, he picked up a comb next to the sink and ran it through the damp, newly bleached strands. As long as he wore a completely different style of clothing—which he planned to do—the blond hair changed his looks just enough to keep him from being spotted as the guy who had wiped out the attackers at the airport.

There was also a likelihood that the SNP mole—who had poisoned the two Department of Defense shooters—had also seen him. He could only hope he didn’t encounter that man again because a simple change in hair color and dress style wouldn’t fool him. Cassetti had shaved both his head and beard, yet left a mustache and goatee. The change was remarkable.

The Executioner studied the young journalist as he slid a white T-shirt over his head and shoulders. Cassetti was young and, according to the CIA report, still letting his hormones get in the way of his judgment. He was also short-tempered, inwardly angry about the love triangle he didn’t know how to handle and completely inexperienced in real-world fighting. He had proved that inexperience when he’d tried to hit Bolan back at the SNP headquarters. He had telegraphed his standard karate lunge punch so far in advance that the Executioner could have sat down, had lunch and then stood back up before he had to block it.

But the longer the Executioner knew Cassetti, the more he had begun to see a lot of good in the young man, too. When he wasn’t angry about everything, he had a sense of humor, and was starting to calm down to a more even temperament than he’d demonstrated earlier. And if the brief discussion they’d had during the drive from the airport to the hotel after Bolan had rented the nondescript Buick Century Custom was any indication, Cassetti had gotten a good education during his college years.

The young man did know his literature, and the Executioner was hoping he’d be able to help decipher the messages hidden within the limerick.

Of course, there was one other route to deciphering the code he could try, too. And Bolan would take that route in a few minutes when he had the chance.

Sliding into the shoulder rig that carried his Beretta 93-R machine pistol with a sound suppresser threaded onto the barrel, the Executioner shrugged until the Concealex plastic holster fell in place under his left arm. He had not used the 9 mm pistol during the shootout at the airport, so there was no need to reload either the gun or the two extra 15-round magazines that rode at the other end of the rig, under his right arm.

Dropping just below the magazines was a Tanto-tipped knife with a four-and-one-half-inch blade. In the hands of an experienced blade man like the Executioner, it was a deadly weapon.

Last came the .44 Magnum Desert Eagle. The big handgun was difficult to hide. But a man as tall, broad and muscular as the Executioner could pull it off, especially with the loose safari-style jacket, which he would leave unbuttoned for quick access to all of his weapons.

Bolan turned his attention back to Cassetti. At the Learjet—where Bolan had learned from Grimaldi that the repairs were almost finished—the young journalist had chosen a twin pair of Colt Commander .45s as his personal sidearms. The Commanders had slightly shorter barrels than the standard 1911s and now they lay on the bed next to him.

Bolan knew they had been a good choice for the thin, wiry-muscled, young man. They were flat and easy to conceal—even under the lightweight blue tank top Cassetti was wearing. Several extra 10-round magazines—which would extend from the butt of the guns when he inserted them but still work—had been dropped into the back pockets of his faded blue jeans. The tops stuck up and out of the pockets. But with the tail of the tank top untucked, they’d be covered, too.

The Executioner continued to watch Cassetti in his peripheral vision as he sat down on the bed and began tying on a pair of brown suede hiking boots. The young man was cleaning his fingernails with a knife he’d also chosen from the plane’s well-stocked armory. It was a good knife, with a wide four-and-one-half-inch reinforced blade that curved deeply along the belly. Bolan had used it himself on several occasions, and with its reinforced tip and sharpened back edge it could do anything from open an ammo can to take out a sentry by silently cutting his throat.

In the corner, disguised within two black garment bags complete with hangers sticking out of the tops, were the same Heckler & Koch submachine guns Bolan and Grimaldi had used at the airport. The ace pilot had given them a thorough cleaning while repairs were being made on the Learjet, reloaded their magazines with the same RBCD rounds they’d also used and packed them away in the disguised coverings.

Bolan straightened the tail of his safari jacket, then walked to the mirror above the desk and took a quick look to make sure he had no telltale bulges showing beneath the garment. When push came to shove, and their enemies’ goal was not only to hurt but kill them, would Cassetti have what it took to pull the trigger? The young man had learned how to break necks and kill men with his bare hands. But only in theory. When the time came to use those techniques for real, could he force himself to do so?

That had yet to be proved.

“Stand up,” the Executioner said, turning toward Cassetti. “Unload both .45s, then cock and lock them, and put them wherever you plan to carry them.”

The expression on Cassetti’s face told Bolan that the young man didn’t like being ordered around. But he followed the Executioner’s instructions just the same, dropping the 8-round magazines already in the weapons to the bed, then pulling back the slide to eject the chambered rounds.

Cassetti didn’t have an ounce of fat around his waist as he lifted his tank top with his left hand. But he sucked in his belly just the same as he jammed both .45s, grips pointing toward each other, into his jeans just in front of his hip bones before letting his tank top fall back over them.

“Now,” the Executioner said, “face the door.”

Again, Cassetti grimaced slightly at the order. It was obvious that he had the heart of a true antiauthoritarian. Such men could be trouble. But once you earned their respect, they would often follow you to hell and back. They were also, more often than not, self-reliant. Thinkers and innovators, problem solvers who did not have to have their hands held every step of the way during violent encounters.

“Now,” Bolan said, “when I give you the word, I want you to draw one of the .45s, disengage the safety and dry fire at the doorknob. Got it?’

“It’s pretty complicated,” Cassetti said sarcastically, “but I’ll do my best to keep up with you.”

“Then go.”

Quickly, Cassetti jerked his tank top up over his weapons and pulled the right-handed Commander out of his belt. He extended his arm out and downward at a forty-five-degree angle, then lifted it almost to eye level and pulled the trigger.

The clank of the firing pin hitting the empty chamber echoed through the hotel room.

Cassetti recocked the gun, flipped the safety back up and dropped it back into his pants.

The Executioner was slightly surprised at both the young man’s speed and efficiency. “All right,” he said. “Now do it left-handed.”

Cassetti did.

“You’re point-shooting, which is good,” the Executioner said as the tank top fell over Cassetti’s guns again. “Who taught you that?”

“My dad,” Cassetti said. “He was in the first Gulf War. Eighty-second Airborne.”

The Executioner frowned. The 1980s and 90s were a sad period for pistol shooting in the armed forces. They had switched their training from point-shooting, to what was called “front sight” shooting, in which the gunman always tried to look at the front sight when he pulled the trigger. That was a fine method for competing in gun games or practicing on the firing range. But it went against every human instinct in a real life-or-death situation when every fiber of a man’s body told him to focus on the threat rather than his front sight.

Point-shooting at close range—up to fifteen yards or so for most men—was faster and more natural. Because it came as instinctively as pointing your finger.