По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

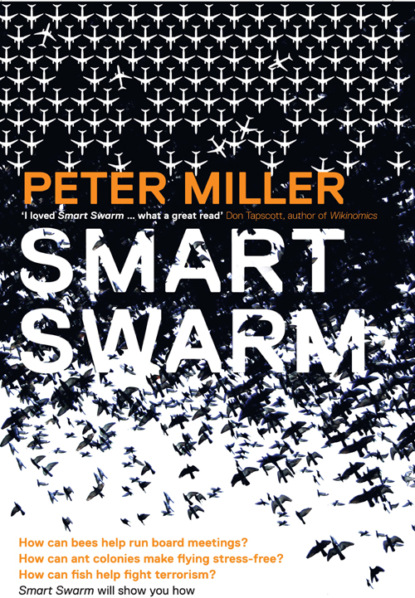

Smart Swarm: Using Animal Behaviour to Organise Our World

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The benefits of diversity are particularly evident in tasks that involve combining information, such as finding a single correct answer to a question. To show how this works, Page takes us back to the quiz show Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? Imagine, he writes, that a contestant has been stumped by a question about the Monkees, the pop group invented for TV who became so popular they sold more records in 1967 than the Beatles and Elvis combined. The question: Which person from the following list was not a member of the Monkees?

(a) Peter Tork

(b) Davy Jones

(c) Roger Noll

(d) Michael Nesmith

Let’s say the studio audience this afternoon has a hundred people in it, Page proposes, and seven of them are former Monkees fans who know that Roger Noll was not a member of the group (he’s actually an economist at Stanford). When asked to vote, these people choose (c). Another ten people recognize two of the names on the list as belonging to the Monkees, leaving Noll and one other name to choose from. Assuming they choose randomly between the two, that means (c) is likely to get another five votes from this group. Of the remaining audience members, fifteen recognize only one of the names, which means another five votes for (c), using the same logic. The final sixty-eight people have no clue, splitting their votes evenly among the four choices, which means another seventeen votes for (c). Add them up and you get thirty-four votes for Roger Noll. If the other names get about twenty-two votes each, as statistical laws suggest, then Noll wins—even though 93 percent of the audience is basically guessing. If the contestant follows the audience’s advice, he climbs another rung on the ladder to the show’s million-dollar prize.

The principle at work in this example, as Page explains, was described in the fourth century B.C. by Aristotle, who noted that a group of people can often find the answer to a puzzle if each member knows at least part of the solution. “For each individual among the many has a share of excellence and practical wisdom, and when they meet together, just as they become in a manner one man, who has many feet, and hands, and senses, so too with regard to their character and thought,” Aristotle writes in Politics. The effect might seem magical, Page notes, but “there is no mystery here. Mistakes cancel one another out, and correct answers, like cream, rise to the surface.”

This does not mean, he cautions, that diversity is a magic wand you can wave at any problem and make it go away. It’s important to consider what kind of task you’re facing. “If a loved one requires open-heart surgery, we do not want a collection of butchers, bakers, and candlestick makers carving open the chest cavity. We’d much prefer a trained heart surgeon, and for good reason,” Page writes. Nor would we expect a committee of people who deeply hate each other to come up with productive solutions. There are limits to the magic of the math.

You have to use common sense when weighing the impact of diversity. For simple tasks, it’s not really necessary (you don’t need a group to add two and two). For truly difficult tasks, the group must be reasonably smart (no one expects monkeys banging on typewriters to come up with the collected works of Shakespeare). The group also must be diverse (otherwise you have nothing more to work with than the smartest expert does). And the group must be large enough and selected from a deep enough pool of individuals (to ensure that the group possesses a wide-ranging mix of skills). Satisfy all four of these criteria, Page says, and you’re good to go.

Surowiecki would emphasize one point in particular: If you want a group to make good decisions, you must ensure that its members don’t interact too much. Otherwise they could influence one another in counterproductive ways through imitation or intimidation—especially intimidation. “In any organization, like a team or company, people tend to pay very close attention to bosses or those with higher status,” Surowiecki says. “That can be very damaging, from my perspective, because one of the great things about the wisdom of crowds, or whatever you want to call it, is that it recognizes that people may have useful things to contribute who aren’t necessarily at the top. They may not be the ones everyone automatically looks to. And that goes by the wayside when people imitate those at the top too closely.”

Diversity. Independence. Combinations of perspectives. These principles should sound familiar. They’re versions of the lessons we learned from the honeybees: Seek a diversity of knowledge. Encourage a friendly competition of ideas. Use an effective mechanism to narrow your choices. What was smart for the honeybees is smart for groups of people, too.

It’s not so easy, after all, to make decisions as efficiently as honeybees do. With millions of years of evolution behind them, they’ve fashioned an elegant system that fits their needs and abilities perfectly. If we could do as well—if we could harness our diversity to overcome our bad habits—then perhaps people wouldn’t say that we’re still thinking with caveman brains.

Caveman Brains

Imagine this scenario: Intelligence agencies have turned up evidence of a plot by at least three individuals to carry out a terrorist attack in Boston. Exactly what kind of attack is not known, but it might be related to a religious conference being held in the city. Possible targets include the Episcopal Church of St. Paul, Harvard’s Center for World Religion, One Financial Plaza, and the Federal Reserve Bank. Security cameras at each building have captured blurry images of ten different individuals acting suspiciously during the past week, though none have been positively identified as terrorists. Intercepted e-mail between suspects appears to include simple code words, such as “crabs” for explosives and “bug dust” for diversions. Time’s running out to crack the plot.

This was the fictional situation presented to fifty-one teams of college students during a CIA-funded experiment at Harvard not long ago. Each four-person team was simulating a counterterrorism task force. Their assignment: sort through the evidence to identify the terrorists, figure out what they were planning to do, and determine which building was their target. They were given an hour to complete the task.

The experiment was organized by Richard Hackman and Anita Woolley, a pair of social psychologists, with collaborators Margaret Giabosi and Stephen Kosslyn. A few weeks earlier, they’d given the students a battery of tests to find out who was good at remembering code words (verbal working memory) and who was good at identifying faces from a large set of photos (face-recognition ability), skills that tap separate functions of the brain. They used the results of these tests to assign students to teams, arranging it so that some teams had two experts (students who scored unusually high on either verbal or visual skills) and two generalists (students who scored average on both skills), and some teams had all generalists. This was important, because they wanted to find out if a team’s cognitive diversity really affected its performance as strongly as did its level of skills.

The researchers had another goal. They wanted to see if a group’s performance might be improved if its members took time to explicitly sort out who was good at what, put each person to work on an appropriate task—such as decoding e-mails or studying images—and then talked about the information they turned up. Would it enable them, in other words, to exploit not only their diversity of knowledge but also their diversity of abilities? To find out, they told all of the teams how each member had scored on the skills tests, but they coached only half of the teams on how to make task assignments. They left the other half on their own.

The researchers had hired a mystery writer to dream up the terrorist scenario. The solution was that a fictional anti-Semitic group was planning to spray a deadly virus in the vault at the Federal Reserve Bank where Israel stores its gold, thereby making it unavailable for months and supposedly bankrupting that nation. “We made it a little bit ridiculous because we didn’t want to scare anybody,” Woolley says.

Who did the best job at solving the puzzle? Not surprisingly, the most successful teams—the ones that correctly identified the target, terrorists, and plot details—were those with experts that applied their skills appropriately and actively collaborated with one another. What no one expected, however, was that the teams with experts who made little effort to coordinate their work would do so poorly. They did even worse, in fact, than teams that had no experts at all.

“We filmed all the teams and watched them several times,” Woolley says. “What seems to happen is that, when two of the people are experts and two are not, there’s a status thing that goes on. The two that aren’t experts defer to the two that are, when in fact you really need information from all four to answer the problem correctly.”

Why was this disturbing? Because that’s how many analytic teams function in real life, Woolley says, whether they’re composed of intelligence agents interpreting data, medical personnel making a diagnosis, or financial teams considering an investment. Smart people with special skills are often put together to make important decisions, but they’re frequently left on their own to figure out how to apply those skills as a group. Because they’re good at what they do, many talented people don’t feel it’s necessary to collaborate. They don’t see themselves as a group. As a result, they often fail to make the most of their collective talents and end up making a poor decision.

“We’ve done a bunch of field research in the intelligence community and I can tell you that no agency, not the Defense Department, not the CIA, not the FBI, not the state police, not the Coast Guard, not drug enforcement, has everything they need to figure out what’s going on,” Hackman told a workshop on collective intelligence at MIT. “That means that most antiterrorism work is done by teams from multiple organizations with their own strong cultures and their own ways of doing things. And the stereotypes can be awful. You see the intelligence people looking at the people from law enforcement saying, You guys are not very smart, all you care about is your badge and your gun. We know how to do this work, okay? And the law enforcement people saying, You guys wouldn’t recognize a chain of evidence if you tripped over it. All you can do is write summa cum laude essays in political science at Princeton. That’s the level of stereotyping. And they don’t get over it, so they flounder.”

Personal prejudice is a poor guide to decision making, of course. But it’s only one in a long list of biases and bad habits that routinely hinder our judgment. During the past fifty years, psychologists have identified numerous “hidden traps” that subvert good decisions, whether they’re made by business executives, political leaders, or consumers at the mall. Many can be traced to the sort of mental shortcuts we use every day to manage life’s challenges—the rules of thumb we apply unconsciously because our brains, unlike those of ants or bees, weren’t designed to tackle problems collectively.

Consider the trap known as “anchoring,” which results from our tendency to give too much weight to the first thing we hear. Suppose someone asks you the following questions:

Is the population of Chicago greater than 3 million?

What’s your best estimate of Chicago’s population?

Chances are, when you answer the second question, you’ll be basing it on the first. You can’t help it. That’s the way your brain is hardwired. If the number in the first question was 10 million, your answer to the second one would be significantly higher. Late-night TV commercials exploit this kind of anchoring. “How much would you pay for this slicer-dicer?” the announcer asks. “A hundred dollars? Two hundred? Call now and pay only nineteen ninety-five.”

Then there’s the “status quo” trap, which stems from our preference not to rock the boat. All things being equal, we prefer options that keep things the way they are, even if there’s no logic behind that choice. That’s one reason mergers often run into trouble, according to John Hammond, Ralph Keeney, and Howard Raiffa, who described “The Hidden Traps in Decision Making” in the Harvard Business Review. Instead of taking swift action to restructure a company following a merger, combining departments and eliminating redundancies, many executives wait for the dust to settle, figuring they can always make adjustments later. But the longer they wait, the more difficult it becomes to change the status quo. The window of opportunity closes.

Nobody likes to admit a mistake, after all. Which leads to the “sunk-cost” trap, in which we choose courses of action that justify our earlier decisions—even if they no longer seem so brilliant. Hanging on to a stock after it has taken a nosedive may not show the best judgment. Yet many people do exactly that. In the workplace, we might avoid admitting to a blunder—hiring an incompetent person, for example—because we’re afraid it will make us look bad in the eyes of our superiors. But the longer we let the problem drag on, the worse it can be for everyone.

As if these flaws weren’t enough, we also ignore facts that don’t support our beliefs. We overestimate our ability to make accurate predictions. We cling to inaccurate information even after it has been disproved. And we accept the most recent bit of trivia as gospel. As individuals, in short, we tend to make a lot of mistakes with even simple decisions. Throw a problem at us that involves interactions of multiple variables and you’re asking for trouble.

Yet increasingly, analysts say, that’s exactly what business leaders are dealing with. “Managers have long relied on their intuition to make strategic decisions in complex circumstances, but in today’s competitive landscape, your gut is no longer a good enough guide,” writes Eric Bonabeau, who is now chief scientist at Icosystem, a consulting company near Boston. Often managers rise to the top of their organizations because they’ve been able to make tough decisions in the face of uncertainty, he writes. But when you’re dealing with complexity, intuition “is not only unlikely to help, it is often misleading. Human intuition, which arguably has been shaped by biological evolution to deal with the environment of hunters and gatherers, is showing its limits in a world whose dynamics are getting more complex by the minute.”

We aren’t very good at making difficult decisions in complex situations, in other words, because our brains haven’t had time to evolve. “We have the brains of cavemen,” Bonabeau says. “That’s fine for problems that don’t require more than a caveman’s brain. But many other problems require a little more thinking.”

One way to handle such problems, as we’ve seen, is to harness the cognitive diversity of a group. When Jeff Severts asked his prediction market to estimate the probability of the new Best Buy store opening on time, he tapped into a wide range of perspectives, and the result was an unbiased assessment of the situation. In a way, that’s what most of us would hope would happen, since society counts on groups to be more reliable than individuals. That’s why we have juries, committees, corporate boards, and blue-ribbon panels. But groups aren’t perfect either. Unless they’re carefully structured and given an appropriate task, groups don’t automatically produce the best solution. As decades of research have demonstrated, groups have many bad habits of their own.

Take their tendency to ignore useful information. When a group discusses an issue, it can spend too much time going over stuff everybody already knows, and too little time considering facts or points of view known only by a few. Psychologists call this “biased sampling.” Let’s say your daughter’s PTA is planning a fund-raiser. The president asks everybody at the meeting for ideas about what to sell. The group spends the whole time talking about cookies, because everybody knows how to make them, even though many people might have special family recipes for cupcakes, fudge, or other goodies that might be popular. Because these suggestions never come up, the group may squander its own diversity.

Many mistakes made by groups can be traced to rushing a decision. Instead of taking time to put together a full range of options, a group may settle on a choice prematurely, then spend time searching for evidence to support that choice. Perhaps the most notorious example of rushing a decision is a phenomenon that psychologist Irving Janis described as groupthink, in which a tightly knit team blunders into a fiasco through a combination of unfortunate traits, including a domineering leader, a lack of diversity among team members, a disregard of outside information, and a high level of stress. Such teams develop an unrealistic sense of confidence about their decision making and a false sense of consensus. Outside opinions are dismissed. Dissension is perceived as disloyalty. Janis was thinking, in particular, of John F. Kennedy’s reckless decision to back the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in 1961, when historians say that President Kennedy and a small circle of advisors acted in isolation without serious analysis or debate. As a result, when some twelve hundred Cuban exiles landed on the southern coast of the island, they were promptly defeated by the Cuban army and tossed into jail.

Decisions made by groups, in short, can be as dysfunctional as those made by individuals. But they don’t have to be, as the swarm bees have already shown us. When groups contain the right mix of individuals and are carefully structured, they can compensate for mistakes by pooling together a greater diversity of knowledge and skills than any of their members could obtain on their own. That was the lesson of the experiments Hackman and Woolley conducted in Boston: Students did better at identifying the terrorists when they sorted out the skills of each team member and gave everyone a chance to contribute information and opinions to the process. Simply by drawing from a wider range of experiences, as Scott Page’s theorems proved, groups can put together a bigger bag of tricks for problem solving. And when it comes to making predictions, like how many gift cards will be purchased this month, groups can cancel out personal biases and bad habits by combining information and attitudes into a reliable group judgment.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: