По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

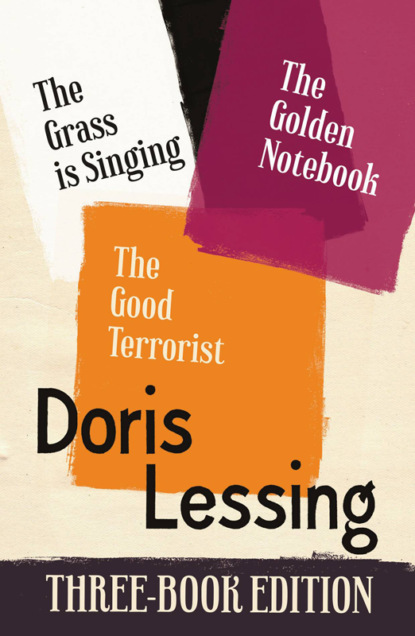

Doris Lessing Three-Book Edition: The Golden Notebook, The Grass is Singing, The Good Terrorist

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Nagged at him, eh? Oh well, women are pretty bad that way, in this country, very often. Aren’t they, Slatter?’ The voice was easy, intimate, informal. ‘My old woman drives me mad – it’s something about this country. They have no idea how to deal with niggers.’

‘Needs a man to deal with niggers,’ said Charlie. ‘Niggers don’t understand women giving them orders. They keep their own women in their right place.’ He laughed. The Sergeant laughed. They turned towards each other, even including Tony, in an unmistakable relief. The tension had broken; the danger was over: once again, he had been bypassed, and the interview, it seemed, was over. He could hardly believe it.

‘But look here,’ he said. Then he stopped. Both men turned to look at him, a steady, grave, irritated look on their faces. And the warning was unmistakable! It was the warning that might have been given to a greenhorn who was going to let himself down by saying too much. This realization was too much for Tony. He gave in; he washed his hands of it. He watched the other two in utter astonishment: they were together in mood and emotion, standing there in perfect understanding; the understanding was unrealized by themselves, the sympathy unacknowledged; their concerted handling of this affair had been instinctive: they were completely unaware of there being anything extraordinary, even anything illegal. And was there anything illegal, after all? This was a casual talk, on the face of it, nothing formal about it now that the notebook was shut – and it had been shut ever since they had reached the crisis of the scene.

Charlie said, turning towards the sergeant, ‘Better get her out of here. It is too hot to wait.’

‘Yes,’ said the policeman, moving to give orders accordingly.

And that brutally matter-of-fact remark, Tony realized afterwards, was the only time poor Mary Turner was referred to directly. But why should she be? – except that this was really a friendly talk between the farmer who had been her next neighbour, the policeman who had been in her house on his rounds as a guest, and the assistant who had lived there for some weeks. It wasn’t a formal occasion, this: Tony clung to the thought. There was a court case to come yet, which would be properly conducted.

‘The case will be a matter of form, of course,’ said the Sergeant, as if thinking aloud, with a look at Tony. He was standing by the police car, watching the native policemen lift the body of Mary Turner, which was wrapped in a blanket, into the back seat. She was stiff; a rigid outstretched arm knocked horribly against the narrow door; it was difficult to get her in. At last it was done and the door shut. And then there was another problem: they could not put Moses the murderer into the same car with her; one could not put a black man close to a white woman, even though she were dead, and murdered by him. And there was only Charlie’s car, and mad Dick Turner was in that, sitting staring in the back. There seemed to be a feeling that Moses, having committed a murder, deserved to be taken by car; but there was no help for it, he would have to walk, guarded by the policemen, wheeling their bicycles, to the camp.

All these arrangements completed, there was a pause.

They stood there beside the cars, in the moment of parting, looking at the red-brick house with its shimmering hot roof, and the thick encroaching bush, and the group of black men moving off under the trees on their long walk. Moses was quite impassive, allowing himself to be directed without any movement of his own. His face was blank. He seemed to be staring straight into the sun. Was he thinking he would not see it much longer? Impossible to say. Regret? Not a sign of it. Fear? It did not seem so. The three men looked at the murderer, thinking their own thoughts, speculative, frowning, but not as if he were important now. No, he was unimportant: he was the constant, the black man who will thieve, rape, murder, if given half a chance. Even for Tony he no longer mattered; and his knowledge of the native mind was too small to give him any basis for conjecture.

‘And what about him?’ asked Charlie, jerking his thumb at Dick Turner. He meant: where does he come in, as far as the court case is concerned?

‘He looks to me as if he won’t be good for much,’ said the Sergeant, who after all had plenty of experience of death, crime and madness.

No, for them the important thing was Mary Turner, who had let the side down; but even she, since she was dead, was no longer a problem. The one fact that remained still to be dealt with was the necessity for preserving appearances. Sergeant Denham understood that: it was part of his job, though it would not appear in regulations, was rather implicit in the spirit of the country, the spirit in which he was soaked. Charlie Slatter understood it, none better. Still side by side, as if one impulse, one regret, one fear, moved them both, they stood together in that last moment before they left the place, giving their final silent warning to Tony, looking at him gravely.

And he was beginning to understand. He knew now, at least, that what had been fought out in the room they had just left was nothing to do with the murder as such. The murder, in itself, was nothing. The struggle that had been decided in a few brief words – or rather, in the silences between the words – had had nothing to do with the surface meaning of the scene. He would understand it all a good deal better in a few months, when he had ‘become used to the country’. And then he would do his best to forget the knowledge, for to live with the colour bar in all its nuances and implications means closing one’s mind to many things, if one intends to remain an accepted member of society. But, in the interval, there would be a few brief moments when he would see the thing clearly, and understand that it was ‘white civilization’ fighting to defend itself that had been implicit in the attitude of Charlie Slatter and the Sergeant, ‘white civilization’ which will never, never admit that a white person, and most particularly, a white woman, can have a human relationship, whether for good or for evil, with a black person. For once it admits that, it crashes, and nothing can save it. So, above all, it cannot afford failures, such as the Turners’ failure.

For the sake of those few lucid moments, and his half-confused knowledge, it can be said that Tony was the person present who had the greatest responsibility that day. For it would never have occurred to either Slatter or the Sergeant that they might be wrong: they were upheld, as in all their dealings with the black-white relationship, by a feeling of almost martyred responsibility. Yet Tony, too, wanted to be accepted by this new country. He would have to adapt himself, and if he did not conform, would be rejected: the issue was clear to him, he had heard the phrase ‘getting used to our ideas’ too often to have any illusions on the point. And, if he had acted according to his by now muddled ideas of right and wrong, his feeling that a monstrous injustice was being done, what difference would it make to the only participant in the tragedy who was neither dead or mad? For Moses would be hanged in any case; he had committed a murder, that fact remained. Did he intend to go on fighting in the dark for the sake of a principle? And if so, which principle? If he had stepped forward then, as he nearly did, when Sergeant Denham climbed finally into the car, and had said: ‘Look here, I am just not going to shut up about this,’ what would have been gained? It is certain that the Sergeant would not have understood him. His face would have contracted, his brow gone dark with irritation, and, taking his foot off the clutch, he would have said, ‘Shut up about what? Who has asked you to shut up?’ And then, if Tony had stammered out something about responsiblity, he would have looked significantly at Charlie and shrugged. Tony might have continued, ignoring the shrug and its implication of his wrongmindedness: ‘If you must blame somebody, then blame Mrs Turner. You can’t have it both ways. Either the white people are responsible for their behaviour, or they are not. It takes two to make a murder – a murder of this kind. Though, one can’t really blame her either. She can’t help being what she is. I’ve lived here, I tell you, which neither of you has done, and the whole thing is so difficult it is impossible to say who is to blame.’ And then the Sergeant would have said, ‘You can say what you think right in court.’ That is what he would have said, just as if the issue had not been decided – though ostensibly it had never been mentioned – less than ten minutes before. ‘It’s not a question of blame,’ the Sergeant might have said. ‘Has anyone said anything about blame? But you can’t get away from the fact that this nigger has murdered her, can you?’

So Tony said nothing and the police car went off through the trees. Charlie Slatter followed in his car with Dick Turner. Tony was left in the empty clearing, with an empty house.

He went inside, slowly, obsessed with the one clear image that remained to him after the events of the morning, and which seemed to him the key to the whole thing: the look on the Sergeant’s and Slatter’s faces when they looked down at the body; that almost hysterical look of hate and fear.

He sat down, his hand to his head, which ached badly; then got up again and fetched from a dusty shelf in the kitchen a medicine bottle marked ‘Brandy’. He drank it off. He felt shaky in the knees and in the thighs. He was weak, too, with repugnance against this ugly little house which seemed to hold within its walls, even in its very brick and cement, the fears and horror of the murder. He felt suddenly as if he could not bear to stay in it, not for another moment.

He looked up at the bare crackling tin of the roof, that was warped with the sun, at the faded gimcrack furniture, at the dusty brick floors covered with ragged animal skins, and wondered how those two, Mary and Dick Turner, could have borne to live in such a place, year in and year out, for so long. Why, even the little thatched hut where he lived at the back was better than this! Why did they go on without even so much as putting in ceilings? It was enough to drive anyone mad, the heat in this place.

And then, feeling a little muddle-headed (the heat made the brandy take effect at once), he wondered how all this had begun, where the tragedy had started. For he clung obstinately to the belief, in spite of Slatter and the Sergeant, that the causes of the murder must be looked for a long way back, and that it was they which were important. What sort of woman had Mary Turner been, before she came to this farm and had been driven slowly off balance by heat and loneliness and poverty? And Dick Turner himself – what had he been? And the native – but here his thoughts were stopped by lack of knowledge. He could not even begin to imagine the mind of a native.

Passing his hand over his forehead, he tried desperately, and for the last time, to achieve some sort of a vision that would lift the murder above the confusions and complexities of the morning, and make of it, perhaps, a symbol, or a warning. But he failed. It was too hot. He was still exasperated by the attitude of the two men. His head was reeling. It must be over a hundred in this room, he thought angrily, getting up from his chair, and finding that his legs were unsteady. And he had drunk, at the most, two tablespoons of brandy! This damned country, he thought, convulsed with anger. Why should this happen to me, getting involved with a damned twisted affair like this, when I have only just come: and I really can’t be expected to act as judge and jury and compassionate God into the bargain!

He stumbled on to the verandah, where the murder had been committed the night before. There was a ruddy smear on the brick, and a puddle of rainwater was tinged pink. The same big shabby dogs were licking at the edges of the water, and cringed away when Tony shouted at them. He leaned against the wall and stared over the soaked greens and browns of the veld to the kopjes, which were sharp and blue after the rain; it had poured half the night. He realized, as the sound grew loud in his ears, that cicadas were shrilling all about him. He had been too absorbed to hear them. It was a steady, insistent screaming from every bush and tree. It wore on his nerves. ‘I am getting out of this place,’ he said suddenly. ‘I am getting out of it altogether. I am going to the other end of the country. I wash my hands of the thing. Let the Slatters and the Denhams do as they like. What has it got to do with me?’

That morning, he packed his things and walked over to the Slatters’ to tell Charlie he would not stay. Charlie seemed indifferent, even relieved; he had been thinking there was no need of a manager now that Dick would not come back.

After that the Turners’ farm was run as an overflow for Charlie’s cattle. They grazed all over it, even up to the hill where the house stood. It was left empty: it soon fell down.

Tony went back into town, where he hung round the bars and hotels for a while, waiting to hear of some job that would suit him. But his early carefree adaptability was gone. He had grown difficult to please. He visited several farms, but each time went away: farming had lost its glitter for him. At the trial, which was as Sergeant Denham had said it would be, a mere formality, he said what was expected of him. It was suggested that the native had murdered Mary Turner while drunk, in search of money and jewellery.

When the trial was over, Tony loafed about aimlessly until his money was finished. The murder, those few weeks with the Turners, had affected him more than he knew. But his money being gone, he had to do something in order to eat. He met a man from Northern Rhodesia, who told him about the copper mines and the wonderfully high salaries. They sounded fantastic to Tony. He took the next train to the copper belt, intending to save some money and start some business on his own account. But the salaries, once there, did not seem so good as they had from a distance. The cost of living was high, and then, everyone drank so much…Soon he left underground work and was a kind of manager. So, in the end, he sat in an office and did paperwork, which was what he had come to Africa to avoid. But it wasn’t so bad really. One should take things as they came. Life isn’t as one expects it to be – and so on; these were the things he said to himself when depressed, and was measuring himself against his early ambitions.

For the people in ‘the district’, who knew all about him by hearsay, he was the young man from England who hadn’t the guts to stand more than a few weeks of farming. No guts, they said. He should have stuck it out.

2 (#ulink_2456d8f7-49da-5fd9-9c6f-84e0ab4a62a5)

As the railway lines spread and knotted and ramified all over Southern Africa, along them, at short distances of a few miles, sprang up little dorps that to a traveller appear as insignificant clusters of ugly buildings, but which are the centres of farming districts perhaps a couple of hundred miles across. They contain the station building, the post office, sometimes a hotel, but always a store.

If one was looking for a symbol to express South Africa, the South Africa that was created by financiers and mine magnates, the South Africa which the old missionaries and explorers who charted the Dark Continent would be horrified to see, one would find it in the store. The store is everywhere. Drive ten miles from one and you come on the next; poke your head out of the railway carriage, and there it is; every mine has its store, and many farms.

It is always a low single-storeyed building divided into segments like a strip of chocolate, with grocery, butchery and bottle-store under one corrugated iron roof. It has a high dark wooden counter, and behind the counter shelves hold anything from distemper mixture to toothbrushes, all mixed together. There are a couple of racks holding cheap cotton dresses in brilliant colours, and perhaps a stack of shoe-boxes, or a glass case for cosmetics or sweets. There is the unmistakable smell, a smell compounded of varnish, dried blood from the killing yards behind, dried hides, dried fruit and strong yellow soap. Behind the counter is a Greek, or a Jew, or an Indian. Sometimes the children of this man, who is invariably hated by the whole district as a profiteer and an alien, are playing among the vegetables because the living quarters are just behind the shop.

For thousands of people up and down Southern Africa the store is the background to their childhood. So many things centred round it. It brings back, for instance, memories of those nights when the car, after driving endlessly through a chilly, dusty darkness, stopped unexpectedly in front of a square of light where men lounged with glasses in their hands, and one was carried out into the brilliantly-lit bar for a sip of searing liquid ‘to keep the fever away’. Or it might be the place where one drove twice a week to collect mail, and to see all the farmers from miles around buying their groceries, and reading letters from Home with one leg propped on the running-board of the car, momentarily oblivious to the sun, the square of red dust where the dogs lay scattered like flies on meat and the groups of staring natives – momentarily transported back to the country for which they were so bitterly homesick, but where they would not choose to live again: ‘South Africa gets into you,’ these self-exiled people would say, ruefully.

For Mary, the word ‘Home’ spoken nostalgically, meant England, although both her parents were South Africans and had never been to England. It meant ‘England’ because of those mail-days, when she slipped up to the store to watch the cars come in, and drive away again laden with stores and letters and magazines from overseas.

For Mary, the store was the real centre of her life, even more important to her than to most children. To begin with, she always lived within sight of it, in one of those little dusty dorps. She was always having to run across to bring a pound of dried peaches or a tin of salmon for her mother, or to find out whether the weekly newspaper had arrived. And she would linger there for hours, staring at the piles of sticky coloured sweets, letting the fine grain stored in the sacks round the walls trickle through her fingers, looking covertly at the little Greek girl whom she was not allowed to play with, because her mother said her parents were dagos. And later, when she grew older, the store came to have another significance: it was the place where her father bought his drink. Sometimes her mother worked herself into a passion of resentment, and walked up to the barman, complaining that she could not make ends meet, while her husband squandered his salary in drink. Mary knew, even as a child, that her mother complained for the sake of making a scene and parading her sorrows: that she really enjoyed the luxury of standing there in the bar while the casual drinkers looked on, sympathetically; she enjoyed complaining in a hard sorrowful voice about her husband. ‘Every night he comes home from here,’ she would say, ‘every night! And I am expected to bring up three children on the money that is left over when he chooses to come home.’ And then she would stand still, waiting for the condolences of the man who pocketed the money which was rightly hers to spend for the children. But he would say at the end, ‘But what can I do? I can’t refuse to sell him drink, now can I?’ And at last, having played out her scene and taken her fill of sympathy, she would walk away across the expanse of red dust to her house, holding Mary by the hand – a tall, scrawny woman with angry, unhealthy brilliant eyes. She made a confidante of Mary early. She used to cry over her sewing while Mary comforted her miserably, longing to get away, but feeling important too, and hating her father.

This is not to say that he drank himself into a state of brutality. He was seldom drunk as some men were, whom Mary saw outside the bar, frightening her into a real terror of the place. He drank himself every evening into a state of cheerful fuddled good humour, coming home late to a cold dinner, which he ate by himself. His wife treated him with a cold indifference. She reserved her scornful ridicule of him for when her friends came to tea. It was as if she did not wish to give her husband the satisfaction of knowing that she cared anything for him at all, or felt anything for him, even contempt and derision. She behaved as if he were simply not there for her. And for all practical purposes he was not. He brought home the money, and not enough of that. Apart from that he was a cipher in the house, and knew it. He was a little man, with dull ruffled hair, a baked-apple face, and an air of uneasy though aggressive jocularity. He called visiting petty officials ‘sir’; and shouted at the natives under him; he was on the railway, working as a pumpman.

And then, as well as being the focus of the district, and the source of her father’s drunkenness, the store was the powerful, implacable place that sent in bills at the end of the month. They could never be fully paid: her mother was always appealing to the owner for just another month’s grace. Her father and mother fought over these bills twelve times a year. They never quarrelled over anything but money; sometimes, in fact, her mother remarked drily that she might have done worse: she might, for instance, be like Mrs Newman, who had seven children; she had only three mouths to fill, after all. It was a long time before Mary saw the connection between these phrases, and by then there was only one mouth to feed, her own; for her brother and sister both died of dysentery one very dusty year. Her parents were good friends because of this sorrow for a short while: Mary could remember thinking that it was an ill wind that did no one good; because the two dead children were both so much older than she that they were no good to her as playmates, and the loss was more than compensated by the happiness of living in a house where there were suddenly no quarrels, with a mother who wept, but who had lost that terrible hard indifference. That phase did not last long, however. She looked back on it as the happiest time of her childhood.

The family moved three times before Mary went to school; but afterwards she could not distinguish between the various stations she had lived in. She remembered an exposed dusty village that was backed by a file of bunchy gum trees, with a square of dust always swirling and settling because of passing ox-waggons; with hot sluggish air that sounded several times a day with the screaming and coughing of trains. Dust and chickens; dust and children and wandering natives; dust and the store – always the store.

Then she was sent to boarding school and her life changed. She was extremely happy, so happy that she dreaded going home at holiday-times to her fuddled father, her bitter mother, and the fly-away little house that was like a small wooden box on stilts.

At sixteen she left school and took a job in an office in town: one of those sleepy little towns scattered like raisins in a dry cake over the body of South Africa. Again, she was very happy. She seemed born for typing and shorthand and book-keeping and the comfortable routine of an office. She liked things to happen safely one after another in a pattern, and she liked, particularly, the friendly impersonality of it. By the time she was twenty she had a good job, her own friends, a niche in the town. Then her mother died and she was virtually alone in the world, for her father was five hundred miles away, having been transferred to yet another station. She hardly saw him: he was proud of her, but (which was more to the point) left her alone. They did not even write; they were not the writing sort. Mary was pleased to be rid of him. Being alone in the world had no terrors for her at all, she liked it. And by dropping her father she seemed in some way to be avenging her mother’s sufferings. It had never occurred to her that her father, too, might have suffered. ‘About what?’ she would have retorted, had anyone suggested it. ‘He’s a man, isn’t he? He can do as he likes.’ She had inherited from her mother an arid feminism, which had no meaning in her own life at all, for she was leading the comfortable carefee existence of a single woman in South Africa, and she did not know how fortunate she was. How could she know? She understood nothing of conditions in other countries, had no measuring rod to assess herself with.

It had never occurred to her to think, for instance, that she, the daughter of a petty railway official and a woman whose life had been so unhappy because of economic pressure that she had literally pined to death, was living in much the same way as the daughters of the wealthiest in South Africa, could do as she pleased – could marry, if she wished, anyone she wanted. These things did not enter her head. ‘Class’ is not a South African word; and its equivalent, ‘race’, meant to her the office boy in the firm where she worked, other women’s servants, and the amorphous mass of natives in the streets, whom she hardly noticed. She knew (the phrase was in the air) that the natives were getting ‘cheeky’. But she had nothing to do with them really. They were outside her orbit.

Till she was twenty-five nothing happened to break the smooth and comfortable life she led. Then her father died. That removed the last link that bound her to a childhood she hated to remember. There was nothing left to connect her with the sordid little house on stilts, the screaming of trains, the dust, and the strife between her parents. Nothing at all! She was free. And when the funeral was over, and she had returned to the office, she looked forward to a life that would continue as it had so far been. She was very happy: that was perhaps her only positive quality, for there was nothing else distinctive about her, though at twenty-five she was at her prettiest. Sheer contentment put a bloom on her: she was a thin girl, who moved awkwardly, with a fashionable curtain of light-brown hair, serious blue eyes, and pretty clothes. Her friends would have described her as a slim blonde: she modelled herself on the more childish-looking film stars.

At thirty nothing had changed. On her thirtieth birthday she felt a vague surprise that did not even amount to discomfort – for she did not feel any different – that the years had gone past so quickly. Thirty! It sounded a great age. But it had nothing to do with her. At the same time she did not celebrate this birthday; she allowed it to be forgotten. She felt almost outraged that such a thing could happen to her, who was no different from the Mary of sixteen.

She was by now the personal secretary of her employer, and was earning good money. If she had wanted, she could have taken a flat and lived the smart sort of life. She was quite presentable. She had the undistinguished, dead-level appearance of South African white democracy. Her voice was one of thousands: flattened, a little sing-song, clipped. Anyone could have worn her clothes. There was nothing to prevent her living by herself, even running her own car, entertaining on a small scale. She could have become a person on her own account. But this was against her instinct.

She chose to live in a girls’ club, which had been started, really, to help women who could not earn much money, but she had been there so long no one thought of asking her to leave. She chose it because it reminded her of school, and she had hated leaving school. She liked the crowds of girls, and eating in a big dining-room, and coming home after the pictures to find a friend in her room waiting for a little gossip. In the Club she was a person of some importance, out of the usual run. For one thing she was so much older than the others. She had come to have what was almost the rôle of a comfortable maiden aunt to whom one can tell one’s troubles. For Mary was never shocked, never condemned, never told tales. She seemed impersonal, above the little worries. The stiffness of her manner, her shyness, protected her from many spites and jealousies. She seemed immune. This was her strength, but also a weakness that she would not have considered a weakness: she felt disinclined, almost repelled, by the thought of intimacies and scenes and contacts. She moved among all those young women with a faint aloofness that said as clear as words: I will not be drawn in. And she was quite unconscious of it. She was very happy in the Club.

Outside the girls’ club, and the office, where again she was a person of some importance, because of the many years she had worked there, she led a full and active life. Yet it was a passive one, in some respects, for it depended on other people entirely. She was not the kind of woman who initiates parties, or who is the centre of a crowd. She was still the girl who is ‘taken out’.

Her life was really rather extraordinary: the conditions which produced it are passing now, and when the change is complete, women will look back on them as on a vanished Golden Age.

She got up late, in time for the office (she was very punctual) but not in time for breakfast. She worked efficiently, but in a leisurely way, until lunch. She went back to the club for lunch. Two more hours’ work in the afternoon and she was free. Then she played tennis, or hockey or swam. And always with a man, one of those innumerable men who ‘took her out’, treating her like a sister: Mary was such a good pal! Just as she seemed to have a hundred women friends, but no particular friend, so she had (it seemed) a hundred men, who had taken her out, or were taking her out, or who had married and now asked her to their homes. She was friend to half the town. And in the evening she always went to sundowner parties that prolonged themselves till midnight, or danced, or went to the pictures. Sometimes she went to the pictures five nights a week. She was never in bed before twelve or later. And so it had gone on, day after day, week after week, year after year. South Africa is a wonderful place: for the unmarried white woman. But she was not playing her part, for she did not get married. The years went past; her friends got married; she had been bridesmaid a dozen times; other people’s children were growing up; but she went on as companionable, as adaptable, as aloof and as heart-whole as ever, working as hard enjoying herself as she ever did in the office, and never for one moment alone, except when she was asleep.

She seemed not to care for men. She would say to her girls, ‘Men! They get all the fun.’ Yet outside the office and the club her life was entirely dependent upon men, though she would have most indignantly repudiated the accusation. And perhaps she was not so dependent upon them really, for when she listened to other people’s complaints and miseries she offered none of her own. Sometimes her friends felt a little put off, and let down. It was hardly fair, they felt obscurely, to listen, to advise, to act as a sort of universal shoulder for the world to weep on, and give back nothing of her own. The truth was she had no troubles. She heard other people’s complicated stories with wonder, even a little fear. She shrank away from all that. She was a most rare phenomenon: a woman of thirty without love troubles, headaches, backaches, sleeplessness or neurosis. She did not know how rare she was.

And she was still ‘one of the girls’. If a visiting cricket team came to town and partners were needed, the organizers would ring up Mary. That was the kind of thing she was good at: adapting herself sensibly and quietly to any occasion. She would sell tickets for a charity dance or act as a dancing partner for a visiting full-back with equal amiability.

And she still wore her hair little-girl fashion on her shoulders, and wore little-girl frocks in pastel colours, and kept her shy, naive manner. If she had been left alone she would have gone on, in her own way, enjoying herself thoroughly, until people found one day that she had turned imperceptibly into one of those women who have become old without ever having been middle-aged: a little withered, a little acid, hard as nails, sentimentally kindhearted, and addicted to religion or small dogs.

They would have been kind to her, because she had ‘missed the best things of life’. But then there are so many people who don’t want them: so many for whom the best things have been poisoned from the start. When Mary thought of ‘home’ she remembered a wooden box shaken by passing trains; when she thought of marriage she remembered her father coming home red-eyed and fuddled; when she thought of children she saw her mother’s face at her children’s funeral – anguished, but as dry and as hard as rock. Mary liked other people’s children but shuddered at the thought of having any of her own. She felt sentimental at weddings, but she had a profound distaste for sex; there had been little privacy in her home and there were things she did not care to remember; she had taken good care to forget them years ago.