По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

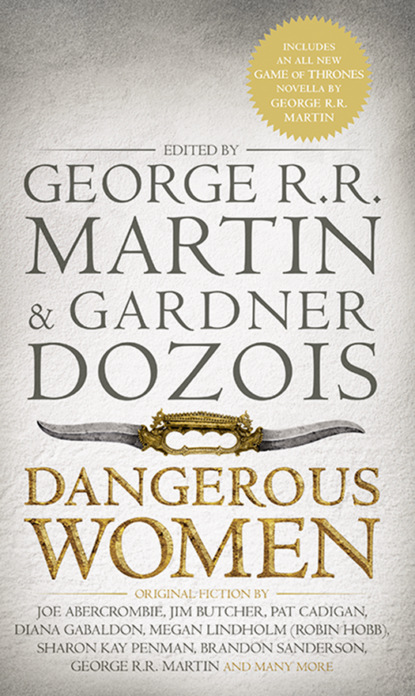

Dangerous Women

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

That night, he remembered a story she had told him long ago. It seemed impossible he’d forgotten it. Or maybe it just seemed different now, making it seem like something new. Something uncovered, an old sunken box you find in the basement smelling strong and you’re afraid to open it.

It was back when they were dating, when her roommate was always around and they had no place to be alone. They would have thrilling bouts in his car, and she loved to crawl into the backseat and lie back, hoisting a leg high over the headrest and begging him for it.

It was after the first or second time, back when it was all so crazy and confusing and his head was pounding and starbursting, that Lorie curled against him and talked and talked about her life, and the time she stole four Revlon eyeslicks from CVS and how she had slept with a soggy-eared stuffed animal named Ears until she was twelve. She said she felt she could tell him anything.

Somewhere in the blur of those nights—nights when he, too, told her private things, stories about babysitter crushes and shoplifting Matchbox cars—that she told him the story.

How, when she was seven, her baby brother was born and she became so jealous.

“My mom spent all her time with him, and left me alone all day,” she said. “So I hated him. Every night, I would pray that he would be taken away. That something awful would happen to him. At night, I’d sneak over to his crib and stare at him through the little bars. I think maybe I figured I could think it into happening. If I stared at him long enough and hard enough, it might happen.”

He had nodded, because this is how kids could be, he guessed. He was the youngest and wondered if his older sister thought things like this about him. Once, she smashed his finger under a cymbal and said it was an accident.

But she wasn’t done with her story and she snuggled closer to him and he could smell her powdery body and he thought of all its little corners and arcs, how he liked to find them with his hands, all the soft, hot places on her. Sometimes it felt like her body was never the same body, like it changed under his hands. I’m a witch, a witch.

“So one night,” she said, her voice low and sneaky, “I was watching him through the crib bars and he was making this funny noise.”

Her eyes glittered in the dark of the car.

“I leaned across, sticking my hands through the rails,” she said, snaking her hand towards him. “And that’s when I saw this piece of string dangling on his chin, from his pull toy. I starting pulling it, and pulling it.”

He watched her tugging the imaginary string, her eyes getting bigger and bigger.

“Then he let out this gasp,” she said, “and started breathing again.”

She paused, her tongue clicking.

“My mom came in at just that moment. She said I saved his life,” she said. “Everyone did. She bought me a new jumper and the hot-pink shoes I wanted. Everyone loved me.”

A pair of headlights flashed across them and he saw her eyes, bright and brilliant.

“So no one ever knew the real story,” she said. “I’ve never told anyone.”

She smiled, pushing herself against him.

“But now I’m telling you,” she said. “Now I have someone to tell.”

“Mr. Ferguson, you told us, and your cell phone records confirm, that you began calling your wife at 5:50 p.m. on the day of your daughter’s disappearance. Finally, you reached her at 6:45. Is that right?”

“I don’t know,” he said, this the eighth, ninth, tenth time they’d called him in. “You would know better than me.”

“Your wife said she was at the coffee place at around five. But we tracked down a record of your wife’s transaction. It was at 3:45.”

“I don’t know,” he said, rubbing at the back of his neck, the prickling there. He realized he had no idea what they might tell him. No idea what might be coming.

“So what do you think your wife was doing for three hours?”

“Looking for this woman. Trying to find her.”

“She did make some other calls during that time. Not to the police, of course. Or even you. She made a call to a man named Leonard Drake. Another one named Jason Patrini.”

One sounded like an old boyfriend—Lenny someone—the other he didn’t even know. He felt something hollow out inside him. He didn’t know who they were even talking about anymore, but it had nothing to do with him.

The female detective walked in, giving her partner a look.

“Since she was making all these calls, we could track her movements. She went to the Harbor View Mall.”

“Would you like to see her on the security camera footage there?” the female detective asked. “We have it now. Did you know she bought a tank top.”

He felt nothing.

“She also went to the quickie mart. The cashier just IDed her. She used the bathroom. He said she was in there a long time and when she came out, she had changed clothing.

“Would you like to see the footage there? She looks like a million bucks.”

She slid a grainy photo across the desk. A young woman in a tank top and hoodie tugged low over her brow. She was smiling.

“That’s not Lorie,” he said softly. She looked too young, looked like she looked when he met her, a little elfin beauty with a flat stomach and pigtails and a pierced navel. A hoop he used to tug. He’d forgotten about that. She must have let it seal over.

“I’m sure this is tough to hear, Mr. Ferguson,” the male detective said. “I’m sorry.”

He looked up. The detective did look very sorry.

“What did you say to them?” he asked.

Lorie was sitting in the car with him, a half block from the police station.

“I don’t know if you should say anything to them anymore,” he said. “I think maybe we should call a lawyer.”

Lorie was looking straight ahead, at the strobing lights from the intersection. Slowly, she lifted her hand to the edges of her hair, combing them thoughtfully.

“I explained,” she said, her face dark except for a swoop of blue from the car dealership sign, like a tadpole up her cheek. “I told them the truth.”

“What truth?” he asked. The car felt so cold. There was a smell coming from her, of someone who hasn’t eaten. A raw smell of coffee and nail polish remover.

“They don’t believe anything I say anymore,” she said. “I explained how I’d been to the coffee place twice that day. Once to get a juice for Shelby and then later for coffee for me. They said they’d look into it, but I could see how it was on their faces. I told them so. I know what they think of me.”

She turned and looked at him, the car moving fast, sending red lights streaking up her face. It reminded him of a picture he once saw in a National Geographic of an Amazon woman, her face painted crimson, a wooden peg through her lip.

“Now I know what everyone thinks of me,” she said, and turned away again.

It was late that night, his eyes wide open, that he asked her. She was sound asleep, but he said it.

“Who’s Leonard Drake? Who’s Jason whatever?”

She stirred, shifted to face him, her face flat on the sheet.

“Who’s Tom Ferguson? Who is he?