По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

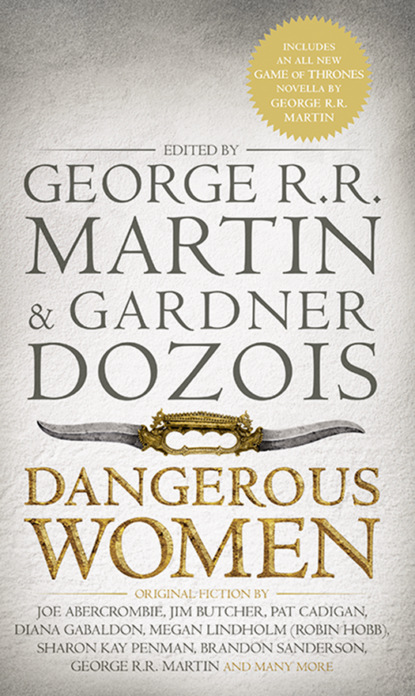

Dangerous Women

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

At some point in the middle of the night, there was a stirring next to him, her body shifting hard. It felt like something was happening.

“Kirsten,” she mumbled.

“What?” he asked. “What?”

Suddenly she half sat up, her elbows beneath her, looking straight ahead.

“Her daughter’s name was Kirsten,” she said, her voice soft and tentative. “I just remembered. Once, when we were talking, she said her daughter’s name was Kirsten. Because she liked how it sounded with Krusie.”

He felt something loosen inside him, then tighten again. What was this?

“Her last name was Krusie with a K,” she said, her face growing more animated, her voice more urgent. “I don’t know how it was spelled, but it was with a K. I can’t believe I just remembered. It was a long time ago. She said she liked the two Ks. Because she was two Ks. Katie Krusie. That’s her name.”

He looked at her and didn’t say anything.

“Katie Krusie,” she said. “The woman at the coffee place. That’s her name.”

He couldn’t seem to speak or even move.

“Are you going to call?” she said. “The police?”

He found he couldn’t move. He was afraid somehow. So afraid he couldn’t breathe.

She looked at him, paused, and then reached across him, grabbing for the phone herself.

As she talked to the police, told them, her voice now clear and firm, what she’d remembered, as she told them she would come to the station, would leave in five minutes, he watched her, his hand over his own heart, feeling it beating so hard it hurt.

“We believe we have located the Krusie woman,” the female detective said. “We have officers heading there now.”

He looked at both of them. He could feel Lorie beside him, breathing hard. It had been less than a day since Lorie first called.

“What are you saying?” he said, or tried to. No words came out.

Katie-Ann Krusie had no children, but told people she did, all the time. After a long history of emotional problems, she had spent a fourteen-month stint at the state hospital following a miscarriage.

For the past eight weeks she had been living in a rental in Torring, forty miles away with a little blond girl she called Kirsten.

After the police released a photo of Katie-Ann Krusie on Amber Alert, a woman who worked at a coffee chain in Torring recognized her as a regular customer, always ordering extra milk for her babies.

“She sure sounded like she loved her kids,” the woman said. “Just talking about them made her so happy.”

The first time he saw Shelby again, he couldn’t speak at all.

She was wearing a shirt he’d never seen and shoes that didn’t fit and she was holding a juice box the policeman had given her.

She watched him as he ran down the hall toward her.

There was something in her face that he had never seen before, knew hadn’t been there before, and he knew in an instant he had to do everything he could to make it gone.

That was all he would do, if it took him the rest of his life to do it.

The next morning, after calling everyone, one by one, he walked into the kitchen to see Lorie sitting next to Shelby, who was eating apple slices, her pinkie finger curled out in that way she had.

He sat and watched her and Shelby asked him why he was shaking and he said because he was glad to see her.

It was hard to leave the room, even to answer the door when his mother and sister came, when everyone started coming.

Three nights later, at the big family dinner, the Welcome Home dinner for Shelby, Lorie drank a lot of wine and who could blame her, everyone was saying.

He couldn’t either, and he watched her.

As the evening carried on, as his mother brought out an ice cream cake for Shelby, as everyone huddled around Shelby, who seemed confused and shy at first and slowly burst into something beautiful that made him want to cry again—as all these things were occurring—he had one eye on Lorie, her quiet, still face. On the smile there, which never grew or receded, even when she held Shelby in her lap, Shelby nuzzling her mother’s wine-flushed neck.

At one point he found her standing in the kitchen and staring into the sink; it seemed to him she was staring down into the drain.

It was very late, or even early, and Lorie wasn’t there.

He thought she had gotten sick from all the wine, but she wasn’t in the bathroom either.

Something was turning in him, uncomfortably, as he walked into Shelby’s room.

He saw her back, naked and white from the moonlight. The plum-colored underpants she’d slept in.

She was standing over Shelby’s crib, looking down.

He felt something in his chest move.

Then, slowly, she kneeled, peeking through the crib rails, looking at Shelby.

It looked like she was waiting for something.

For a long time he stood there, five feet from the doorway, watching her watching their sleeping baby.

He listened close for his daughter’s high breaths, the stop and start of them.

He couldn’t see his wife’s face, only that long white back of hers, the notches of her spine. Mirame quemar etched on her hip.

He watched her watching his daughter, and knew he could not ever leave this room. That he would have to be here forever now, on guard. There was no going back to bed.

Cecelia Holland

Cecelia Holland is one of the world’s most highly acclaimed and respected historical novelists, ranked by many alongside other giants in that field such as Mary Renault and Larry McMurtry. Over the span of her thirty-year career, she’s written more than thirty historical novels, including The Firedrake,Rakóssy,Two Ravens,Ghost on the Steppe,TheDeath of Attila, Hammer for Princes,The King’s Road,Pillar of the Sky,The Lords of Vaumartin,Pacific Street,The Sea Beggars,The Earl, The Kings in Winter,The Belt of Gold, and more than a dozen others. She also wrote the well-known science fiction novel Floating Worlds, which was nominated for a Locus Award in 1975, and of late has been working on a series of fantasy novels, including The Soul Thief, The Witches’ Kitchen,The Serpent Dreamer,Varanger, and The King’s Witch. Her most recent books are the novels The High City,Kings of the North, and The Secret Eleanor.

In the high drama that follows, she introduces us to the ultimate dysfunctional family, whose ruthless, clashing ambitions threw England into bloody civil war again and again over many long years: King Henry II, his queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, and their eight squabbling children. All deadly as cobras. Even the littlest one.

NORA’S SONG (#ulink_8affa8e5-43c1-5161-a225-705431b5771e)

MONTMIRAIL,