По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

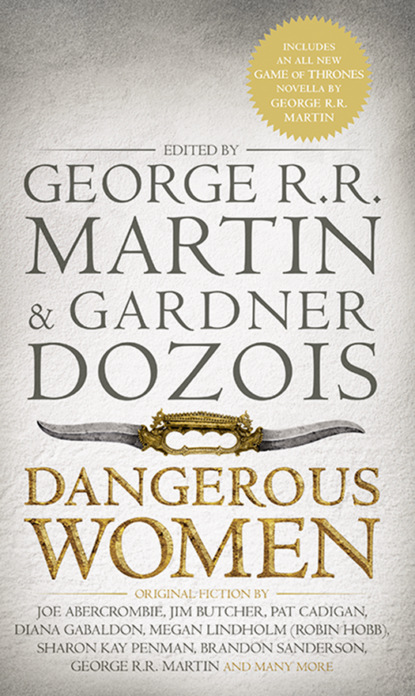

Dangerous Women

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Your mother is wicked.”

Nora pushed away, angry. “My mother is not—”

“Sssh. You’ll wake everybody up. I’m sorry. I’m sorry. It’s just everybody says so. I didn’t mean it. You aren’t a baby.” Alais touched her, pleading. “Are you still my friend?”

Nora thought the whole matter of being friends to be harder than she had expected. Surreptitiously, she pressed her palm against her own bony chest.

Alais snuggled in beside her. “If we’re to be friends, we have to stay close together. Where are we going next?”

Nora pulled the cover around her, the thickness of cloth between her and Alais. “I hope to Poitiers, with Mama. I hope I will go there, the happiest court in the whole world.” In a flash of temper she blurted out, “Any place would be better than Fontrevault. My knees are so sore.”

Alais laughed. “A convent? They put me in convents. They even made me wear nun clothes.”

Nora said, “Oh, I hate that! They’re so scratchy.”

“And they smell.”

“Nuns smell,” Nora said. She remembered something her mother said. “Like old eggs.”

Alais giggled. “You’re funny, Nora. I like you a lot.”

“Well, you have to like my mother too, if you want to go to Poitiers.”

Again, Alais’ hand came up and touched Nora, stroking her. “I will. I promise.”

Nora cradled her head on her arm, pleased, and drowsy. Maybe Alais was not so bad after all. She was a helpless maiden, and Nora could defend her, like a real knight. Her eyelids drooped; for an instant, before she fell asleep, she felt the horse under her again, galloping.

Nora had saved bread crumbs from her breakfast; she was scattering them on the windowsill when the nurse called. She kept on scattering. The little birds were hungry in the winter. The nurse grabbed her by the arm and towed her away.

“Come here when I call you!” The nurse briskly stuffed her headfirst into a gown. Nora struggled up through the mass of cloth until she got her head out. “Now sit down so I can brush your hair.”

Nora sat; she looked toward the window again, and the nurse pinched her arm. “Sit still!”

She bit her lips together, angry and sad. She wished the nurse off to Germany. Hunched on the stool, she tried to see the window through the corner of her eye.

The brush dragged through her hair. “How do you get your hair so snarled?”

“Ooow!” Nora twisted away from the pull of the brush, and the nurse wrestled her back onto the stool.

“Sit! This child is a devil.” The brush smacked her hard on the shoulder. “Wait until we get you back to the convent, little devil.”

Nora stiffened all over. On the next stool, Alais turned suddenly toward her, wide-eyed. Nora slid off the stool.

“I’m going to find my Mama!” She started toward the door. The nurse snatched at her and she sidestepped out of reach and moved faster.

“Come back here!”

“I’m going to find my Mama,” Nora said, and gave the nurse a hard look, and pulled the door open.

“Wait for me,” said Alais.

The servingwomen came after them; Nora went on down the stairs, hurrying, just out of reach. She hoped her Mama was down in the hall. On the stairs, she slipped by some servants coming up from below and they got in the nurses’ way and held them back. Alais was right behind her, wild-eyed.

“Is this all right? Nora?”

“Come on.” Gratefully she saw that the hall was full of people; that meant her mother was there, and she went in past men in long stately robes, standing around waiting, and pushed in past them all the way up to the front.

There her mother sat, and Richard also, standing beside her; the Queen was reading a letter. A strange man stood humbly before her, his hands clasped, while she read. Nora went by him.

“Mama.”

Eleanor lifted her head, her brows arched. “What are you doing here?” She looked past Nora and Alais, into the crowd, brought her gaze back to Nora, and said, “Come sit down and wait; I’m busy.” She went back to the letter in her hand. Richard gave Nora a quick, cheerful grin. She went on past him, behind her Mama’s chair, and turned toward the room. The nurses were squeezing in past the crowd of courtiers, but they could not reach her now. Alais leaned against her, pale, her eyes blinking.

In front of them, her back to them, Eleanor in her heavy chair laid the letter aside. “I’ll give it thought.”

“Your Grace.” The humble man bowed and backed away. Another, in a red coat, stepped forward, a letter in his hand. Reaching for it, the Queen glanced at Richard beside her.

“Why did your father want to see you last night?”

Alais whispered, “What are you going to do?” Nora bumped her with her elbow; she wanted to listen to her brother.

Richard was saying, “He asked me where Boy was.” He shifted his weight from foot to foot. “He was drunk.”

The Queen was reading the new letter. She turned toward the table on her other hand, picked up a quill, and dipped it into the pot of ink. “You should sign this also, since you are Duke now.”

At that, Richard puffed up, making himself bigger, and his shoulders straightened. The Queen turned toward Nora.

“What is this now?”

“Mama.” Nora went up closer to the Queen. “Where are we going? After here.”

Her mother’s green eyes regarded her; a little smile curved her lips. “Well, to Poitiers, I thought.”

“I want to go to Poitiers.”

“Well, of course,” her Mama said.

“And Alais too?”

The Queen’s eyes shifted toward Alais, back by the wall. The smile flattened out. “Yes, of course. Good day, Princess Alais.”

“Good day, your Grace.” Alais dipped into a little bow. “Thank you, your Grace.” She turned a bright happy look at Nora, who cast her a broad look of triumph. She looked up at her mother, glad of her, who could do anything.

“You said you’d protect us, remember?”

The Queen’s smile widened, and her head tipped slightly to one side. “Yes, of course. I’m your mother.”

“And Alais too?”