По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

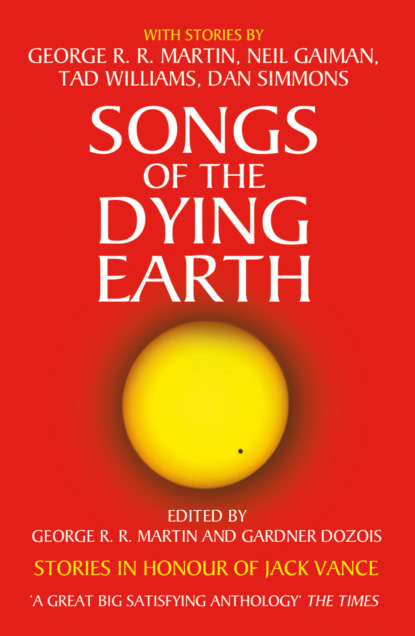

Songs of the Dying Earth

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Frogskin Cap HOWARD WALDROP (#litres_trial_promo)

A Night at the Tarn House GEORGE R.R. MARTIN (#litres_trial_promo)

An Invocation of Incuriosity NEIL GAIMAN (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

THANK YOU, MR. VANCE By Dean Koontz (#ulink_21fc2ad5-7405-5911-82c3-75a74e3c9d04)

IN 1966, at 21, fresh from college, I was a fool and possibly deranged, although not seriously dangerous. I was a well-read fool, especially in science fiction. For twelve years, I pored through at least a book a week in that genre. I felt that I belonged in one of the other worlds or far futures of those tales more than I did in the world and time in which I’d been born, less because I had a wide romantic streak than because I had low self-esteem and longed to shed the son-of-the-town-drunk identity that fate had given me.

During the first five years that I wrote for a living, I produced mostly science fiction. I was not good at it. I sold what I wrote—twenty novels, twenty-eight short stories—but little of that work was memorable, and some was execrable. All these years later, only two of those novels and four or five of those stories might not raise in me a suicidal urge if I reread them.

As a reader, I could tell the difference between great science fiction and the mediocre stuff, and I was drawn to the best, which I often reread. Considering that I was inspired by quality, I should not have turned out so many dreary tales. I was driven to write fast by economic necessity; Gerda and I had been married with $150 and a used car, and though bill collectors were not breaking down the door, the specter of destitution haunted me. A need for money, however, is an insufficient excuse.

In November of 1971, as I moved toward suspense and comic fiction and away from writing SF, I discovered Jack Vance. Considering the hundreds of science fiction novels I had read, I am amazed that I had not until then sampled Mr. Vance’s work. With the intention of reading him, I bought numerous paperbacks of his novels but never opened one, partly because the covers gave me a wrong impression of the contents. On my shelves today is an Ace edition of The Eyes of the Overworld, with a cover price of 45 cents, featuring Cugel the Clever in a flaring pink cape against a background of cartoonish mushrooms like giant genitalia. A 50-cent Ace edition of Big Planet features well-rendered men with ray guns riding badly drawn alien beasts of dubious anatomy. The first book I read by Jack Vance, in November 1971, was Emphyrio, published at the budget-busting price of 75 cents. The cover illustration—perhaps by Jeff Jones—was sophisticated and mystical.

Every writer has a short list of novels that electrified him, that inspired him to try new narrative techniques and fresh stylistic devices. For me, Emphyrio and The Dying Earth are such books. Enthralled with the former, I finished the entire novel without getting up from my armchair, and the same day I read the latter. Between November of 1971 and March of 1972, I read every Jack Vance novel and every piece of his short fiction published to that time—and although many more books were to come, even then he had a long bibliography. Only two other authors have so captivated me that for a time I became immersed in their work to the exclusion of all other reading: on discovering John D. MacDonald, I read thirty-four of his novels in thirty days; and after stubbornly avoiding the fiction of Charles Dickens through high school and college, I read A Tale of Two Cities in 1974 and, over the next three months, every word of fiction Dickens published.

Three things in particular fascinate me about Mr. Vance’s work, the first being a vivid sense of place. Far planets and distant future Earths are so well portrayed that they expand like real and fully colored vistas in the mind’s eye. This is achieved by many means, but primarily by close attention to architecture, first the architecture of key buildings; and in architecture I include interior design. The opening chapters of The Last Castle or The Dragon Masters contain excellent examples of this. Furthermore, when Jack Vance describes the natural world, he does so in the manner neither of a geologist nor a naturalist, nor even as a poet might describe it, but again with an eye for the architecture of nature, not merely of its geological features but also of its flora and fauna. The appearance of things does not intrigue him as much as does their structure. Consequently, his descriptions have depth and complexity from which images arise in the reader’s mind that are in fact poetic. This fascination with structures is evident in every aspect of his fiction, whether it is the structure of languages in The Languages of Pao or the structure of a system of magic in The Dying Earth; and in every novel and novelette he has written, alien cultures and far-future human societies ring true because he gives us the matrix and the lattice, the foundation and the framing on which the visible walls are stood and hung.

The second quality of Mr. Vance’s fiction that fascinates me is his masterly evocation of mood. Each of his works features a subtly modified syntax, scheme of imagery, and coherent system of figures of speech unique to that tale, usually in the service of the implicit meaning but always in the service of mood, which itself grows from his subtext, as it should. I am a sucker for mood. I can forgive a writer many faults if he has the capacity to weave a warp and weft of mood from page one to the end of his story. One of the great things about Jack Vance is that the reader is enthralled by the mood of each piece without having to overlook any faults.

Third, although the people in a Vance science-fiction novel are less real than those in the few mystery novels that he wrote, and are constricted by the conventions of a genre that for many decades valued color and action and cool ideas above characters with depth, they are memorable and, over the body of his work, reveal that the author puts much of himself in the cast members of his tales. The recognition of the author intimately threaded through the tapestry of key characters exposed to me, back there in 1971 and ‘72, a primary reason why my science fiction often failed: as a child raised in poverty and always-pending violence, I had read science fiction largely for escape; therefore, as a writer, I was loath to draw upon my most intense life experiences when writing SF, but instead usually wrote it as sheer escapism.

In spite of the exotic and hypercolorful nature of Jack Vance’s work, reading so much of his fiction in such a short time led me to the realization that I was withholding my soul from the stories that I wrote. If I had remained in science fiction after this moment of enlightenment, I would have written books radically different from those that I had produced between 1967 and 1971. But I immersed myself in the Vance universe as I was moving on to suspense novels like Chase and comic novels like Hanging On; consequently, the lesson I learned from him was applied to everything I wrote after leaving his preferred genre.

I know nothing about Jack Vance’s life, only the fiction that he has written. During those five months in 1971 and ’72, however, and every time I have read a Vance novel in the years since, I have known I am reading the work of someone who enjoyed a largely happy childhood and perhaps an idyllic one. If I’m wrong about this, I don’t want to be corrected. When I settle into a Vance story, I see the sense of wonder and the confidence and the generous spirit of someone who was given a childhood and adolescence free from fear and without want, who used those years to explore the world and, through that exploration, came to embrace it with exuberance. Although my journey to a happy adulthood followed a dark and sometimes desperate path, I do not envy Jack Vance if his route was sunnier; instead, I delight in the worlds of wonder that his experiences made it possible for him to create, and not least of all in that singular world that awaits its end under a fading sun.

The Dying Earth and its sequels comprise one of the most powerful fantasy/science-fiction concepts in the history of the genre. They are packed with adventure but also with ideas, and the vision of uncounted human civilizations stacked one atop another like layers in a phyllo pastry thrills even as it induces a sense of awe—awe in the purest sense of the word—the irresistible yielding of the mind to something so grand in character that it cannot be entirely grasped in all its ramifications but necessarily harbors an ineffable mystery at its heart. The fragility and transience of all things, the nobility of humanity’s struggle against the certainty of an entropic resolution, gives The Dying Earth a poignancy rare in novels of fantastic romance.

Thank you, Mr. Vance, for so much pleasure over the years and for an important moment of enlightenment that made my writing better than it would have been if I had never read Emphyrio, The Dying Earth, and all your other marvelous stories.

PREFACE By Jack Vance (#ulink_33ee018a-04f5-5395-aa63-f664b4292f5d)

I WAS happily surprised when I learned that so many high-echelon, top-drawer writers had undertaken to produce a set of stories based upon some of my early work. Here I must insert a caveat: some may regard the above sentiment as the usual boilerplate. In no way! For a fact, I am properly flattered by this sort of recognition.

I wrote The Dying Earth while working as an able seaman aboard cargo ships, cruising, for the most part, back and forth across the Pacific. I would take my clipboard and fountain pen out on deck, find a place to sit, look out over the long rolling blue swells: ideal circumstances in which to let the imagination wander.

The influences which underlie these stories go back to when I was ten or eleven years old and subscribed to Weird Tales magazine. My favorite writer was C. L. Moore, whom to this day I revere. My mother had a taste for romantic fantasy, and she collected books by an Edwardian writer called Robert Chambers, who is now all but forgotten. He wrote such novels as The King in Yellow, The Maker of Moons, The Tracer of Lost Persons and many others. Also on our bookshelves were the Oz books of L. Frank Baum, as well as Tarzan of the Apes and the Barsoom sequences of Edgar Rice Burroughs. Around this same time Hugo Gernsback began publishing Amazing Stories Monthly and Amazing Stories Quarterly; I devoured both on a regular basis. The fairy tales of Lord Dunsany, an Irish peer, were also a substantial influence; and I cannot ignore the great Jeffery Farnol, another forgotten author, who wrote romantic swashbucklers. In short, it is fair to say that almost everything I read in my early years became transmuted into some aspect of my own style.

Many years after the first publication of The Dying Earth, I used the same setting for the adventures of Cugel and Rhialto, although these books are quite different from the original tales in mood and atmosphere. It is nice to hear that these stories continue to live in the minds of readers and writers alike. To both, and to everyone concerned with the production of this collection, I tip my hat in thanks and appreciation. And to the reader specifically, I promise that you, upon turning the page, will be much entertained.

—Jack Vance

Oakland, 2008

ROBERT SILVERBERG The True Vintage of Erzuine Thale (#ulink_09472186-d8c6-5381-8d09-73829169ab97)

ROBERT SILVERBERG is one of the most famous SF writers of modern times, with dozens of novels, anthologies, and collections to his credit. As both writer and editor (he was editor of the original anthology series New Dimensions, perhaps the most acclaimed anthology series of its era), Silverberg was one of the most influential figures of the Post New Wave era of the ‘70s, and continues to be at the forefront of the field to this very day, having won a total of five Nebula Awards and four Hugo Awards, plus SFWA’s prestigious Grandmaster Award.

His novels include the acclaimed Dying Inside, Lord Valentine’s Castle, The Book of Skulls, Downward to the Earth, Tower of Glass, Son of Man, Nightwings, The World Inside, Born With The Dead, Shadrack In The Furnace, Thorns, Up the Line, The Man in the Maze, Tom O’Bedlam, Star of Gypsies, At Winter’s End, The Face of the Waters, Kingdoms of the Wall, Hot Sky at Morning, The Alien Years, Lord Prestimion, Mountains of Majipoor, two novel-length expansions of famous Isaac Asimov stories, Nightfall and The Ugly Little Boy, The Longest Way Home, and the mosaic novel Roma Eterna. His collections include Unfamiliar Territory, Capricorn Games, Majipoor Chronicles, The Best of Robert Silverberg, The Conglomeroid Cocktail Party, Beyond the Safe Zone, and the ongoing program from Subterranean Press to publish his collected stories, which now runs to four volumes, and Phases of the Moon: Stories from Six Decades, and a collection of early work, In the Beginning. His reprint anthologies are far too numerous to list here, but include The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One and the distinguished Alpha series, among dozens of others. He lives with his wife, writer Karen Haber, in Oakland, California.

Here he takes us south of Almery to languid Ghiusz on the Claritant Peninsula adjoining the Klorpentine Sea, a place as balmy as it gets on The Dying Earth, to meet a poet and philosopher who takes to heart the ancient adage, Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die. Especially drink.

The True Vintage of Erzuine Thale ROBERT SILVERBERG (#ulink_09472186-d8c6-5381-8d09-73829169ab97)

Puillayne of Ghiusz was a man born to every advantage life offers, for his father was the master of great estates along the favored southern shore of the Claritant Peninsula, his mother was descended from a long line of wizards who held hereditary possession of many great magics, and he himself had been granted a fine strongthewed body, robust health, and great intellectual power.

Yet despite these gifts, Puillayne, unaccountably, was a man of deep and ineradicable melancholic bent. He lived alone in a splendid sprawling manse overlooking the Klorpentine Sea, a place of parapets and barbicans, loggias and pavilions, embrasures and turrets and sweeping pilasters, admitting only a few intimates to his solitary life. His soul was ever clouded over by a dark depressive miasma, which Puillayne was able to mitigate only through the steady intake of strong drink. For the world was old, nearing its end, its very rocks rounded and smoothed by time, every blade of grass invested with the essence of a long antiquity, and he knew from his earliest days that futurity was an empty vessel and only the long past supported the fragile present. This was a source of extreme infestivity to him. By assiduous use of drink, and only by such use of it, he could succeed from time to time in lifting his gloom, not through the drink itself but through the practice of his art, which was that of poetry: his wine was his gateway to his verse, and his verse, pouring from him in unstoppable superiloquent abundance, gave him transient release from despond. The verse forms of every era were at his fingertips, be they the sonnet or the sestina or the villanelle or the free chansonette so greatly beloved by the rhyme-loathing poets of Sheptun-Am, and in each of them he displayed ineffable mastery. It was typical of Puillayne, however, that the gayest of his lyrics was invariably tinged with ebon despair. Even in his cups, he could not escape the fundamental truth that the world’s day was done, that the sun was a heat-begrudging red cinder in the darkening sky, that all striving had been in vain for Earth and its denizens; and those ironies contaminated his every thought.

And so, and so, cloistered in his rambling chambers on the heights above the metropole of Ghiusz, the capital city of the happy Claritant that jutted far out into the golden Klorpentine, sitting amidst his collection of rare wines, his treasures of exotic gems and unusual woods, his garden of extraordinary horticultural marvels, he would regale his little circle of friends with verses such as these:

The night is dark. The air is chill.

Silver wine sparkles in my amber goblet.

But it is too soon to drink. First let me sing.

Joy is done! The shadows gather!

Darkness comes, and gladness ends!

Yet though the sun grows dim, My soul takes flight in drink.

What care I for the crumbling walls?

What care I for the withering leaves?

Here is wine!

Who knows? This could be the world’s last night.

Morning, perhaps, will bring a day without dawn.

The end is near. Therefore, friends, let us drink!

Darkness…darkness…

The night is dark. The air is chill.

Therefore, friends, let us drink!

Let us drink!

“How beautiful those verses are,” said Gimbiter Soleptan, a lithe, playful man given to the wearing of green damask pantaloons and scarlet sea-silk blouses. He was, perhaps, the closest of Puillayne’s little band of companions, antithetical though he was to him in the valence of his nature. “They make me wish to dance, to sing—and also…” Gimbiter let the thought trail off, but glanced meaningfully to the sideboard at the farther end of the room.

“Yes, I know. And to drink.”