По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

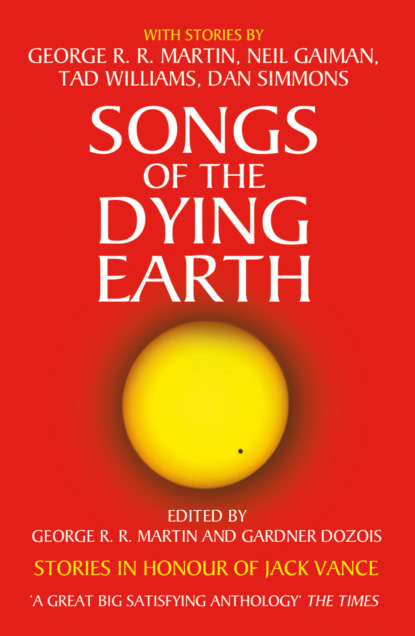

Songs of the Dying Earth

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The night is coming, but what of that?

Do I not glow with pleasure still, and glow, and glow?

There is no darkness, there is no misery

So long as my flask is near!

The flower-picking maidens sing their lovely song by the jade pavilion.

The winged red khotemnas flutter brightly in the trees.

I laugh and lift my glass and drain it to the dregs.

O golden wine! O glorious day!

Surely we are still only in the springtime of our winter

And I know that death is merely a dream

When I have my flask!

AFTERWORD:

I BOUGHT the first edition of The Dying Earth late in 1950, and finding it was no easy matter, either, because the short-lived paperback house that brought it out published it in virtual secrecy. I read it and loved it, and I’ve been re-reading it with increasing pleasure in the succeeding decades and now and then writing essays about its many excellences, but it never occurred to me in all that time that I would have the privilege of writing a story of my own using the setting and tone of the Vance originals. But now I have; and it was with great reluctance that I got to its final page and had to usher myself out of that rare and wondrous world. Gladly would I have remained for another three or four sequences, but for the troublesome little fact that the world of The Dying Earth belongs to someone else. What a delight it was to share it, if only for a little while.

—Robert Silverberg

MATTHEW HUGHES Grolion of Almery (#ulink_24ca1c66-f612-5d7f-92f0-f7ed6667425d)

ALLOWING A stranger to take refuge from the dangers of a dark and demon-haunted night in your house always involves a certain amount of risk for both stranger and householder. Particularly on the Dying Earth, where nothing is as it seems—including the householder and the stranger!

Matthew Hughes was born in Liverpool, England, but spent most of his adult life in Canada before moving back to England last year. He’s worked as a journalist, as a staff speechwriter for the Canadian Ministers of Justice and Environment, and as a freelance corporate and political speechwriter in British Columbia before settling down to write fiction full-time. Clearly strongly influenced by Vance, as an author Hughes has made his reputation detailing the adventures of rogues like Henghis Hapthorn, Guth Bandar, and Luff Imbry who live in the era just before that of The Dying Earth, in a series of popular stories and novels that include Fools Errant, Fool Me Twice, Black Brillion, and Majestrum, with his stories being collected in The Gist Hunter and Other Stories. His most recent books are the novels Hespira, The Spiral Labyrinth, Template, and The Commons.

Grolion of Almery MATTHEW HUGHES (#ulink_24ca1c66-f612-5d7f-92f0-f7ed6667425d)

When next I found a place to insert myself, I discovered the resident in the manse’s foyer, in conversation with a traveler. Keeping myself out of his sightlines, I flew to a spot high in a corner where a roof beam passed through the stone of the outer wall, and settled myself to watch and listen. The resident received almost no visitors—only the invigilant, he of the prodigious belly and eight varieties of scowl, and the steagle knife.

I rarely bothered to attend when the invigilant visited, conserving my energies for whenever my opportunity should come. But this stranger was unusual. He moved animatedly about the room in a peculiar bent-kneed, splay-footed lope, frequently twitching aside the curtain of the window beside the door to peer into the darkness, then checking that the beam that barred the portal was well seated.

“The creature cannot enter,” the resident said. “Doorstep and lintel, indeed the entire house and walled garden, are charged with Phandaal’s Discriminating Boundary. Do you know the spell?”

The stranger’s tone was offhand. “I am familiar with the variant used in Almery. It may be different here.”

“It keeps out what must be kept out; your pursuer’s first footfall across the threshold would draw an agonizing penalty.”

“Does the lurker know this?” said the visitor, peering again out the window.

The resident joined him. “Look,” he said, “see how its nostrils flare, dark against the paleness of its countenance. It scents the magic and hangs back.”

“But not far back.” The dark thatch of the stranger’s hair, which drew down to a point low on his forehead, moved as his scalp twitched in response to the almost constant motion of his features. “It pursued me avidly as I neared the village, growing bolder as the sun sank behind the hills. If you had not opened…”

“You are safe now,” said the resident. “Eventually, the ghoul will go to seek other prey.” He invited the man into the parlor and bade him sit by the fire. I fluttered after them and found a spot on a high shelf. “Have you dined?”

“Only forest foods plucked along the way,” was the man’s answer as he took the offered chair. But though he no longer strode about the room, his eyes went hither and thither, rifling the many shelves and glass-fronted cupboards, as if he cataloged their contents, assigning each item a value and closely calculating the sum of them all.

“I have a stew of morels grown in the inner garden, along with the remnants of yesterday’s steagle,” said the resident. “There is also half a loaf of bannock and a small keg of brown ale.”

The stranger’s pointed chin lifted in a display of fortitude. “We will make the best of it.”

They had apparently exchanged names before I had arrived, for when they were seated with bowls of stew upon their knees and spoons in their hands, the resident said, “So, Grolion, what is your tale?”

The foxfaced fellow arranged his features into an image of nobility beset by unmerited trials. “I am heir to a title and lands in Almery, though I am temporarily despoiled of my inheritance by plotters and schemers. I travel the world, biding my moment, until I return to set matters forcefully aright.”

The resident said, “I have heard it argued that the world as it is now arranged must be the right order of things, for a competent Creator would not allow disequilibrium.”

Grolion found the concept jejeune. “My view is that the world is an arena in which men of deeds and courage drive the flow of events.”

“And you are such?”

“I am,” said the stranger, cramming a lump of steagle into his mouth. He tasted it then began chewing with eye-squinting zest.

Meanwhile, I considered what I had heard, drawing two conclusions: first, that though this fellow who styled himself a grandee of Almery might have sojourned in that well-worn land, he was no scion of its aristocracy—he did not double-strike his tees and dees in the stutter that was affected by Almery’s highest-bred; second, that his name was not Grolion—for if it had been, I would not have been able to recall it, just as I could never retain a memory of the resident’s name,nor the invigilant’s. In my present condition, not enough of me survived to be able to handle true names—nor any of the magics that required memory—else I would have long since exacted a grim revenge.

The resident tipped up his bowl to scoop into his mouth the last sups of stew. His upturned glance fell upon my hiding place. I drew back, but too late. He took from within the neck of his garment a small wooden whistle that hung from a cord about his neck and blew a sonorous note. I heard the flap of leathery wings from the corridor and threw myself into the air in a bid to escape. But the little creature that guarded his bedchamber—the room that had formerly been mine—caught me in its handlike paws. A cruel smile spread across its almost-human face as it tore away my wings and carried me back to its perch above the bedchamber door, where it thrust me into its maw. I withdrew before its stained teeth crushed the life from my borrowed form.

WHEN NEXT I returned, morning light was filtering through gaps in the curtains, throwing a roseate blush onto the gray stone floors. I went from room to room, though I gave a wide berth to the resident’s bedchamber. I found Grolion on the ground floor, in the workroom that overlooks the inner garden, where I had formerly spent my days with my treacherous assistants. He was examining the complex starburst design laid out in colors both vibrant and subtle on the great tray that covered most of the floor. I hovered outside the window that overlooked the inner garden; I could see that the pattern was not far from completion.

Grolion knelt and stretched a fingertip toward an elaborate figure composed in several hues: twin arabesques, intertwined with each other and ornamented with fillips of stylized acaranja leaves and lightning bolts. Just before his cracked and untended fingernail could disarrange the thousand tiny motes, each ashimmer with its own aura of greens and golds, sapphire and amethyst, flaming reds and blazing yellows, a sharp intake of breath from the doorway arrested all motion.

“Back away,” said the resident. “To disturb the pattern before it is completed is highly dangerous.”

Grolion rocked back onto his heels and rose to a standing position. His eyes flitted about the pattern, trying to see it as a whole, but, of course, his effort was defeated. “What is its purpose?” he said.

The resident came into the room and drew him away. “The previous occupant of the manse began it. Regrettably, he was never entirely forthcoming about its hows and how-comes. It has to do with an interplanar anomaly. Apparently, the house sits on a node where several dimensions intersect. Their conjunction creates a weakness in the membranes that separate the planes.”

“Where is this ‘previous occupant?’ Why has he left his work dangerously unfinished?”

The resident made a casual gesture. “These are matters of history, of which our old Earth has already far too much. We need not consider them.”

“True,” said Grolion, “we have only now. But some ‘nows’ are connected to particularly pertinent ‘thens,’ and the prudent man takes note of the connections.”

But the resident had departed the area while he was still talking. The traveler followed and found him in the refectory, only to be caught up in a new topic.

“A gentleman of your discernment will understand,” said the resident, “that my resources are constrained. Much as I delight in your company, I cannot offer unlimited hospitality. I have already overstepped my authority by feeding and sheltering you for a night.”

Grolion looked about him. The manse was well appointed, the furnishings neither spare nor purely utilitarian. The walls of its many chambers were hung with art, the floors lushly carpeted, the lighting soft and shadowless. “As constraints go,” he said, “these seem less oppressive than most.”

“Oh,” said the resident, “none of this is mine own. I am but a humble servant of the village council, paid to tend the premises until the owner’s affairs are ultimately settled. My stipend is scant, and mostly paid in ale and steagle.”