По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

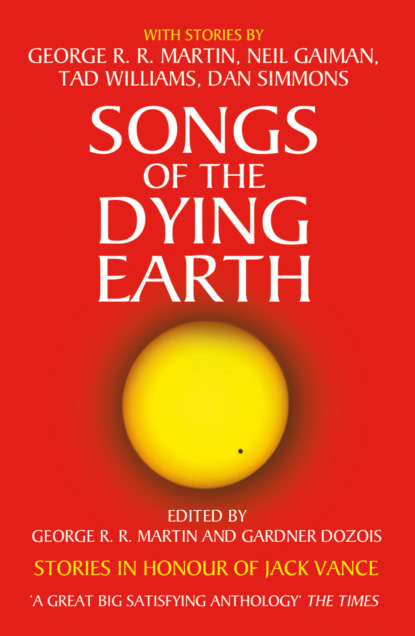

Songs of the Dying Earth

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He received in response an airy gesture of unconcern. “I will give you,” said Grolion, “a promissory note for a handsome sum, redeemable the moment that I am restored to my birthright.”

“The restoration of your fortunes, though no doubt inevitable, is not guaranteed to arrive before the sun goes out.”

Grolion had more to say, but the resident spoke over his remarks. “The invigilant comes every other day to deliver my stipend. I expect him soon. I will ask him to let me engage you as my assistant.”

“Better yet,” said Grolion, his face brightening as he was struck by an original idea, “I might assume a supervisory role. I have a talent for inspiring others to maximum effort.”

The resident offered him a dry eye and an even drier tone. “I require no inspiration. Some small assistance, however, would be welcome. The difficulty will be in swaying the invigilant, who is a notorious groatsqueezer.”

“I am electrified by the challenge.” Grolion rubbed his hands briskly and added, “In the meantime, let us make a good breakfast. I find I argue best on a full stomach.”

The resident sniffed. “I can spare a crust of bannock and half a pot of stark tea. Then we must to work.”

“Would it not be better to establish terms and conditions? I would not want to transgress the local labor code.”

“Have no fear on that score. The village values a willing worker. Show the invigilant that you have already made an energetic contribution, and your argument is half-made before he crosses the doorstep.”

Grolion looked less than fully convinced, but the resident had the advantage of possessing what the other hungered for—be it only a crust and a sup of brackish tea—and thus his views prevailed.

I knew what use the resident would make of the new man. I withdrew to the inner garden and secreted myself in a deep crack in the enclosing wall, from which I could watch without imposing my presence upon the scene. It was not long before, their skimpy repast having been taken, the two men came again under my view.

As I expected, the resident drew the visitor’s attention to the towering barbthorn that dominated one end of the garden. Its dozens of limbs, festooned in trailing succulents, constantly moved as it sampled the air. Several were already lifted and questing in the direction of the two men as it caught their scent even across the full length of the garden.

Sunk as I was in a crack in the wall, I was too distant to hear their conversation, but I could follow the substance of the discussion by the emotions that passed across Grolion’s expressive face and by his gestures of protest. But his complaints were not recognized. With shoulders aslump and reluctance slowing his steps, the traveler trudged to the base of the tree, batting aside two of the creepers that instantly reached for him. He peered into the close-knit branches, seeking the least painful route of ascent. The resident repaired to his workroom, a window of which looked out on the court, enabling him to take note of the new employee’s progress while he worked on the starburst.

I left my hiding place and angled across the wall, meaning to spring onto the man’s shoulder before he ascended the tree. The way he had studied the contents of the parlor showed perspicacity coupled with unbridled greed; I might contrive some means to communicate with him. But so intent on my aims was I that I let myself cross a patch of red sunlight without full care and attention; a fat-bellied spider dropped upon me from its lurking post on the wall above. It swiftly spun a confining mesh of adhesive silk to bind my wings, then deftly flipped me over and pressed its piercing mouthparts against my abdomen. I felt the searing intrusion of its digestive juices dissolving my innards, and withdrew to the place that was both my sanctuary and my prison.

WHEN I was able to observe once more, Grolion and the resident had ceased work to receive the invigilant. I found them in the foyer, in animated discussion. The resident was insistent, arguing that the extra cost of Grolion’s sustenance was well worth the increased productivity that would ensue. The invigilant was pretending to be not easily convinced, noting that a number of previous assistants had been tried and all found wanting.

The resident conceded the point, but added, “The others were unsuitable, vagabonds and wayfarers of poor character. But Grolion is of finer stuff, a scion of Almery’s aristocracy.”

The invigilant turned his belly in the direction of Grolion, who at that point in the proceedings had made his way to the partly open outer door so that he could examine the road outside and the forest across the way. “Are you indeed of gentle birth?”

“What? Oh, yes,” was the answer, then, “Did you see a ghoul lurking in the shadows as you came up the road?”

“We noticed it this morning and drove it off with braghounds and torches,” said the invigilant.

“Indeed?” said Grolion. He edged closer to the door, used the backs of one hand’s fingers to brush it further ajar, craned his neck to regard the road outside from different angles. I saw a surmise take possession of his mobile features.

“Now,” said the invigilant, “let us discuss terms—”

Grolion had turned his head toward the speaker as if intent on hearing his proposal. But as the official began to speak, the traveler threw the door wide, then himself through it. To his evident surprise, the doorway caught him and threw him back into the foyer. He sat on the floor, dazed, then moaned and put his hands to his head as his face showed that his skull had suddenly become home to thunderous pain.

“Phandaal’s Discriminating Boundary,” said the resident. “Besides keeping out what must be kept out, it keeps in what must be kept in.”

“Unspeak the spell,” Grolion said, pain distorting his voice. “The ghoul is gone.”

“He cannot,” said the invigilant. “It can only be removed by he who laid it.”

“The previous occupant?”

“Just so.”

“Then I am trapped here?”

The resident spoke. “As am I, until the work is done. The flux of interplanar energies that will then be released will undo all magics.”

Grolion indicated the invigilant. “He comes and goes.”

“The spell discriminates. Hence the name.”

“Come,” said the invigilant, nudging Grolion with the heel of his staff, “I cannot stand here while you prattle. Rise and pay attention.”

The discussion moved on. The resident’s plan was approved: Grolion would be granted his own allowance of ale, bannock, and steagle, contingent upon his giving satisfaction until the work was finished. Failure to give satisfaction would see a curtailment of the stipend; aggravated failure would lead to punitive confinement in the house’s dank and malodorous crypt.

Grolion proposed several amendments to these terms, though none of them were carried. The invigilant then took from his wallet a folding knife that, when opened, revealed a blade of black stone. He cut the air above the refectory table with it, and from the incisions fell a slab of steagle. He then repeated the process, yielding another slab. Grolion saw what appeared to be two wounds, seemingly in the open air, weeping a liquid like pale blood. Then, in a matter of moments, the gashes closed and he saw only the walls and cupboards of the refectory.

The invigilant left. The resident gave brisk instructions as to the culinary portion of Grolion’s duties—the preparation of steagle involved several arduous steps. Then he went back to the design in the workroom. I sought an opportunity to make contact with Grolion. He was at the preparation table, a heavy wooden mallet in hand, beating at a slab of steagle as if it had offended him by more than the sinewy toughness of its texture and its musty odor. He muttered dire imprecations under his breath. I hovered in front of him, flitting from side to side rhythmically. If I could gain his attention, it would be the first step toward opening a discourse between us.

He looked up and noticed me. I began to fly up and down and at an angle, meaning to trace the first character of the Almery syllabary—it seemed a reasonable opening gambit. He regarded me sourly, still muttering threats and maledictions against the resident. I moved on to the second letter, but as I executed an acute angle, Grolion’s head reared back then shot forward; at the same time, his lips propelled a gobbet of spittle at high speed. The globule caught me in midflight, gluing my wings together and causing me to spiral down to land on the half-beaten steagle. I looked up to see the mallet descending, and then I was gone away again.

BY THE time I had found another carrier, a heavy-bodied rumblebee, several hours had passed. The resident was in the workroom, extending the design with tweezers and templates. The last arm of the sunburst was nearing completion. Once it was done, the triple helix at the center could be laid in, and the work would finally be finished.

Grolion was halfway up the barbthorn, his feet braced against one of its several trunks, a hand gripping an arm-thick branch, fingers carefully spread among the densely sprouting thorns, many of which held the desiccated corpses of small birds and flying lizards that had come to feed on the butterfly larvae that crawled and inched throughout the foliage. The man had not yet noticed that a slim, green tubule, its open end rimmed by tooth-like thorns, had found its way to the flesh between two of his knuckles and was preparing to attach itself and feed; his full attention was on his other hand, carefully cupped around a gold-and-crimson almiranth newly emerged from its cocoon. The insect was drying its translucent wings in the dim sunlight that filtered through the interlaced limbs of the tree.

Grolion breathed gently on the little creature, the warmth of his breath accelerating the drying process. Then, as the almiranth bent and flexed its legs, preparing to spring into first flight, he deftly enclosed it and transferred it to a wide-necked glass bottle that hung from a thong about his neck. The container’s stopper had been gripped in his teeth, but now he pulled the wooden plug free and fixed it into the bottle’s mouth. Laboriously, he began his descent, tearing his pierced hand free of the tubule’s bite. The barbthorn sluggishly pinked and stabbed at him, trying to hold him in place as his shifting weight triggered its feeding response. From time to time, he had to pause to pull loose thorns that snagged his clothing; one or two even managed to pierce his flesh deeply enough that he had to stop and worry them free before he could resume his descent.

Through all of this, Grolion issued a comprehensive commentary on the stark injustice of his situation and on those responsible for it, expressing heartfelt wishes as to events in their futures. The resident and the invigilant featured prominently in these scenarios, as well as others I took to be former acquaintances in Almery. So busy was he with his aspersions that I could find no way to attract his attention. I withdrew to a chink in the garden wall to spy on the resident through the workroom window.

He was kneeling at the edge of the starburst, outlining in silver a frieze of intertwined rings of cerulean blue that traced the edge of one arm. The silver, like all the other pigments of the design, was applied as a fine powder tapped gently from the end of a hollow reed. The resident’s forefinger struck the tube three more times as I watched, then he took up a small brush that bore a single bristle at its end, and nudged an errant flake into alignment.

Grolion appeared in the doorway, grumbling and cursing, to proffer the stoppered jar. The resident shooed him back with a flurry of agitated hand motions, lest any of the blood that dripped from his elbows fall upon the pattern, then he rose and came around the tray to receive the container.

“Watch and remember,” he said, taking the jar to a bench and beckoning Grolion to follow. “If I promote you to senior assistant, this task could be yours.”

“Does that mean someone else will climb the barbthorn?”

The resident regarded him from a great height. “A senior assistant’s duties enfold and amplify those of a junior assistant.”

“So it is merely more work.”

“Your perspective requires modification. The proper understanding is that you command more trust and win more esteem.”

“But my days still consist of ‘Do this,’ and ‘Bring that,’ and nothing to eat but mushrooms from the garden and steagle.”

“The ale is good,” countered the resident. “You must admit that.”

“Somehow it fails to compensate,” said Grolion.