По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

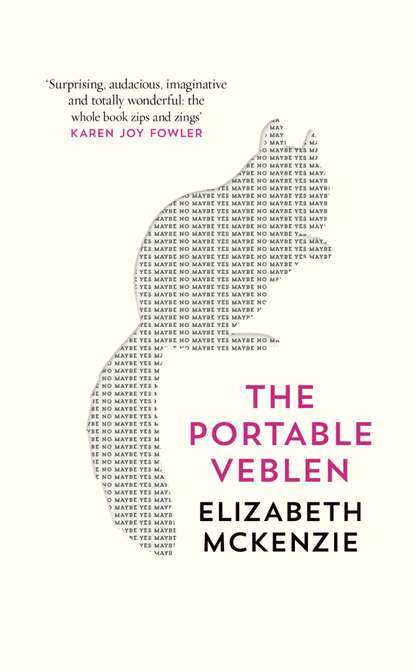

The Portable Veblen: Shortlisted for the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction 2016

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Okay,” said Veblen.

Later that evening, as she was cleaning up, she opened the trash container, and sitting on top, almost in rows as if arranged for viewing, were the turkey balls Paul pretended to have consumed. She started to laugh and asked why he didn’t say something. “Alternately, you could have hidden them better, and I never would have known.”

He said he was sorry, that he hadn’t wanted to spoil dinner.

“But you wanted me to find them later?”

“Mmm. I meant to come back and cover them. I spaced out. Sorry.”

The passive-aggressive lapse seemed duplicitously boyish and charming, but Albertine had been quick to tell her it was a missed opportunity for individuation.

After all, it was unrealistic to expect Paul to be her twin, to think they would react the same way in every situation, always be in the same mood, though there was no denying she craved that. She must withstand all differences, no matter how wrenching and painful. For instance, Paul didn’t like corn on the cob. Of all things! How could a person not like fresh, delicious corn on the cob? And how could she not care?

“I don’t like biting the cob and the kernels taste pasty to me,” Paul had told her.

“Pasty? Then you’ve had really bad corn. Good corn isn’t pasty.”

“Don’t get mad. It’s not like corn is your personal invention.”

“But it’s impossible. Everyone likes it.”

“People with dentures don’t like it.”

“What are you trying to say? Do you have dentures?”

“No! I’m just saying they are a sizable slice of the population.”

“Not anymore. These days most people get implants.”

“Not in rural areas.”

“Okay, fine, whatever! But eating corn together, we’ll never be able to do that?”

“I like other vegetables!” Paul practically yelled.

“Corn is more than a vegetable, it’s practically a national icon.”

“I’m unpatriotic now?”

“If you don’t like corn, it means I’ll probably stop making it. We won’t go on hunts for the best corn stands in summer, driving all over until we find them. You won’t be motivated to shuck it for me. The sound of me gnawing on it will annoy you, so I’ll stop having it. It’ll gradually become a thing of my past, phased out for good.” Veblen was almost ready to cry, and she had reason. Anything and everything her mother disliked had been phased out of her life for good.

“So it’s me or the corn?”

Then she snapped out of it, and they laughed about it, and she came to understand that this recognition of otherness would occur over and over until death they did part, that she couldn’t despair every time it occurred, and that anyway, Paul wasn’t a dictator like her mother … yet it was clear that your choice of mate would shape the rest of your life in ways you couldn’t begin to know. One by one, things he didn’t like would be jettisoned. First squirrels, then turkey meatballs, then corn, then—what next? Marriage could be a continuing exercise in disappearances.

NO TIME TO THINK about this now, for they had reached the long driveway of Veblen’s childhood home, the handle of the hammer, flanked by elephant-sized hummocks of blackberry vines, where Veblen used to pick berries by the gallon to make pies and cobblers and jam. She’d sell them at a table by the road, and help her mother make ends meet. In the fall she put on leather gloves to her elbows to hack the vines back off the driveway, uncovering snakes and lizards and voles. In the spring the vines would start to come back, the green canes growing noticeably by the day, rising straight like spindles before gravity caused them to arc. They grew on the surface the way roots grow underground, in all directions, overlapping, intertwined. The blackberries defined her life in those days—their encroaching threat, their abundant yield. All her old chores came to mind as they rolled up the drive to the familiar crunching of the tires on gravel.

“I never would’ve imagined you growing up somewhere like this,” Paul announced.

“Really?”

“Really.”

No time to think about this either, for Veblen saw her mother advancing out of the house in her best pantsuit, an aqua-colored Thai silk number beneath which new (as in twenty-five years old but saved in the original box for special occasions) Dr. Scholl’s white sandals flashed. She wore them with wool socks. Linus too came out coiffed and ironed, in a blue oxford shirt. They appeared normal, attractive, almost vigorous.

Yet how stiff and formal Veblen’s mother’s posture was, and how tall she stood! She had nearly six inches on her daughter.

Maybe everything would be fine!

“You must be Dr. Paul Vreeland,” her mother said, in a formal style of elocution heard mostly on stage. “Melanie Duffy.”

“Linus Duffy,” said Linus, joining in the hand-grasping ritual.

“We have prepared a nice light lunch to eat outside. Paul, if you would be so kind as to help Linus move the table into the sunshine, we’ll sit right away.”

The men took off behind the house, as the women went inside.

Veblen smiled. “Mom, you look pretty.”

“I’m absolutely miserable,” her mother said, with the men out of earshot. “My shoulders are buckling under the straps of this bra, and my neck is already ruined. I never wear a bra anymore. I despise my breasts. They’re boulders. The nerve of god to do this to women! I’m going to be flat on my back with ice as soon as you leave.”

“You don’t have to wear a bra for our benefit. Take it off. Be yourself.”

“No man wants to see a woman with her breasts hanging down to her navel.”

“Take the straps off your shoulders, then.”

“I’ll try that.”

“I love your suit.”

“Paul’s very good-looking,” her mother said. “But I haven’t sensed the chemistry yet.”

“We’ve been here for five minutes.”

“I hope he’s not in love with himself,” Melanie said. “Oh, good lord.”

Melanie was looking at the ring. They both started to laugh.

“Don’t hold it against me,” Veblen said.

“What was he thinking?” Melanie said. “It’s not you at all.”

“Yeah, I’m trying to get used to it.”

“It’s the ring of a kept woman. Come in the kitchen, I need your help.”

The oatmeal-colored tiles, the chicken-headed canisters, the wall-mounted hand-crank can opener over the sink, gears and magnet always mysteriously greasy, all were in place as they had been for years, and Veblen was proud of her mother’s artwork on the walls around the table—the abstracts in oil and pastels, of landforms and waterways and rocks, sure-handed and dreamy. She sniffed the scent of linseed oil, and from the cupboards a trace of molasses.