По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

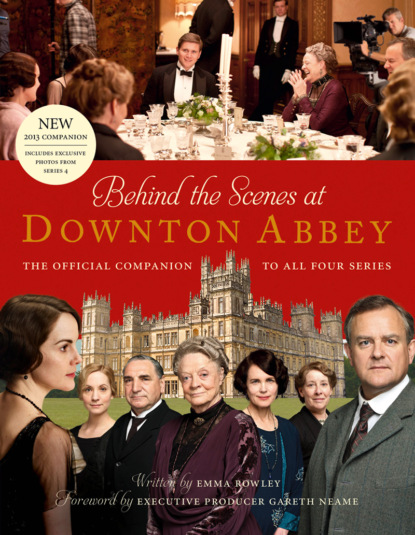

Behind the Scenes at Downton Abbey: The official companion to all four series

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The scene is then blocked out, which means establishing the actors’ various positions on the set, followed by a ‘crew show’ for members of the costume, make-up and art department who are on hand to check everything looks right from their perspective. ‘Everybody troops into the room and stands round the edges as they talk out the entire thing, almost like it’s a little play for the various departments,’ says Evans.

The actors then disappear, to be made completely ready for camera in terms of make-up and costumes, while the focus shifts to the director of photography, Nigel Willoughby, overseer of the show’s cinematography. ‘I’m in charge of the look and the camerawork essentially – so, the lighting, and how we stage scenes,’ he explains. Together with the director, he and his two camera operators discuss how the scene will be filmed, and what camera set-ups would work best. Since its start, Downton tends to have two cameras filming together, unless it is a wide shot.

Next, it is time for the director, too, to retreat, and the set then belongs to Willoughby, his chief electrician (known as the ‘gaffer’) and the electricians for the half an hour or so it will take to arrange the lighting exactly as required. The actors are called back to the set for another run-through in front of the cameras before a bell signals for quiet and the first assistant director shouts ‘Shooting!’ Then he tells the camera operator to roll camera and finally the take will be shot.

Watching the action unfold via a TV monitor will likely be executive producer Liz Trubridge. Having produced the show since its start, she spends much of her time overseeing filming. ‘When she’s on set it is an extremely comfortable place,’ says Evans. ‘The person who is basically the guardian of the spirit of Downton Abbey on set can be called on if people have questions.’

Indeed, Hugh Bonneville believes it is key that, just as the show enjoys a single authorial voice, it has a similar unity in the way it is run by production company Carnival Films. ‘It’s produced by a team of people, but it’s not ten different producers from five different production companies,’ he explains. ‘It’s one clear vision.’

‘There isn’t a single day that’s similar, and that’s part of the joy of this job. As a team, we know the pitfalls – we know what can and will work and what can’t and won’t.’

Liz Trubridge EXECUTIVE PRODUCER

On a day-to-day level, each producer has different responsibilities in managing their role but they have found a shared rhythm to their work. ‘Producing is the most unspecific of all of the jobs in making a show,’ Neame explains. Every producer works slightly differently; there’s no one way to do it. The nature of the job that you do does depend on the show you’re making.’

Neame, the ‘custodian of Downton’, runs the production company, procures the finance from its owners, collaborates with Julian Fellowes on scripts and also approves the casting, editing and post-production work. That leaves Fellowes, who holds the title of executive producer as well as writer, to focus on the scripts, and Trubridge on the ground as the ‘nitty-gritty executive producer, working directly with the directors and actors,’ says Neame. ‘As long as we’ve got a script that we’re happy with, and we’ve chosen the director we’re happy with, I know that Liz will manage all the production side with great creativity, flair and brilliant efficiency.’

Also part of the team are Rupert Ryle-Hodges, who organises the logistics – from when shooting takes place, to how much money is being spent – and Nigel Marchant, who as co-executive producer has a more supervisory role. ‘We are the enablers,’ Trubridge summarises. ‘There isn’t a single day that’s similar, and that’s part of the joy of this job.’ A benefit to having reached a fourth series, she laughs, is that now, ‘as a team, we know the pitfalls – we know what can and will work and what can’t and won’t.’

For all things historical, there is Alastair Bruce, who can often be found on set in the folding chair that bears his affectionate nickname ‘The Oracle’. The author of several books, he was recruited after working with Fellowes on projects such as The Young Victoria. On Downton, attention to historical detail underpins the stories told on screen, he stresses. ‘Normally, historical advisors are broadly ignored in projects or at the sideline, but because of how important my role is to the delivery of Downton Abbey I sit at the front with Liz Trubridge and we work hand-in-hand.’

Bruce’s role, as he sees it, is to help the director to deliver a coherent piece that links to the period – even if the audience is not aware that this is happening. ‘Whereas directors normally try to take Julian’s written words and turn them into a good performance, delivering it to the conscious side of the viewer, I’m the one who’s working in the background trying to make sure that the viewer’s subconscious is also satisfied.’

This means that on set Bruce will be constantly monitoring that whatever action the director wants to shoot fits in with the period and, more specifically, with what would be happening at that time of day in a house of that size. ‘The house is an organism that has a daily structure,’ he explains. ‘The reason why timings are so important is because you cannot run a house like Downton Abbey without closely watching the very specific schedule, so that everybody’s eating at the right hour in order that the house can operate effectively.’

Historical advisor Alastair Bruce is always on hand to ensure every period detail is right.

Executive producer Liz Trubridge (left), pictured with Julian Fellowes, brings calm and order to a busy set.

For the weeks spent filming at Highclere, the grounds beneath the castle become home to the ‘travelling circus’ of trailers that accompanies the production team.

That focus translates into everything from making sure that the costume is coherent with the time of day (not as straightforward as it sounds, since Mr Carson the butler, for instance, would have changed into his eveningwear before Lord Grantham), to what items the servants should be carrying in the background.

The hierarchy, meanwhile, informs everything. ‘I got a bit carried away the other day,’ Sophie McShera revealed. ‘We had the extras in, and I’m really bolshie to the kitchen maids – I tell them it’s because I’m the sous chef. But I was being a bit bossy with the housemaids, too, and realised they are above me! I checked with Alastair and he said, “The kitchen is your domain, but you can’t be too cheeky to them.”’

‘The director’s life is amazing. One day you’re at Highclere with 70 people asking you questions and Lady Carnarvon flitting around, the next it’s two blokes with a computer, having a mid-morning banana!’

David Evans DIRECTOR

The audience may not consciously be aware of these little accuracies, but added together they help transport us to a different world. ‘The viewers feel they are in the space, as they’re legitimately seeing the way a house like that would work,’ says Bruce.

When filming concludes, the post-production process begins – and if directing an episode has something in common with steering an ocean liner, the director returns to the editing suite with a much smaller crew. ‘Just me and Al Morrow [the series editor],’ laughs David Evans. ‘The director’s life is amazing. One day you’re at Highclere with 70 people asking you questions and Lady Carnarvon flitting round, the next it’s just two blokes with a computer, having a mid-morning banana!’

Their task, over roughly a fortnight, is to shape what has been filmed into a coherent whole. The producers will already have been looking at the ‘rushes’ (what has been filmed) every day and spotting anything that may need to be changed or re-shot – which is rare.

Nonetheless, whole scenes will be cut. The scripts are deliberately written long, so that the action has to be squeezed into the running time, creating pace and energy. ‘I like it that way, because then you are genuinely editing something,’ says Neame. ‘The script is a template, it is not the Bible. So when you go into editing, you’re essentially doing another draft of the script. We’re asking: “Does the story work without that scene?” or “Can we just have those four lines from the scene and make it much shorter?” It’s a fun part of the process. You’re going back to the story and you’re retelling it, but this time you’re doing it with pictures and performances, rather than with the words on the page.’

It is a team effort, which can produce as many as ten different iterations of the version, or ‘cut’, from the director and editor, as the producers give their feedback. Whole scenes will be taken out, put back in and switched in order, until Neame, Fellowes and Trubridge are satisfied and it is sent to ITV. Once all the executives involved have signed off the cut, it is ‘locked’. Since the edit process has been carried out on a flexible, digitised version of the film, the finished cut has to be reproduced using the original HD footage to produce the final, or ‘online’, product.

The grading can then take place, whereby the show’s colourist Aidan Farrell, at finishing facility The Farm, digitally enhances the images that have been shot. On a practical level he can make day look like night, or a summer shoot appear to have taken place in deep midwinter, if needed – but his role is really about adding further contrast, hue and texture to the footage, to strengthen the mood and atmosphere. Farrell sees this process as the driving factor behind Downton’s famously rich feel. ‘Going back to series one, at that time period dramas were quite brown, desaturated and old-looking,’ he notes. ‘We wanted a completely new look for the genre, so we went for really bold colours.’ Orchestrating the whole sequence of events is Jess Rundle, the post-production supervisor, who plans the viewings with the executives and makes sure the show comes in on budget and on time.

Finalising the visual aspect of the show is far from the end of this process, however. Just as what is seen on screen is dramatically refined, so is the audio aspect. Each episode is scored with around 20 to 25 minutes of music, made up of some 20 to 30 ‘cues’ – the individual pieces of music that underpin the drama. As a rule, comic scenes tend to use less music, while the more harrowing, emotional storylines demand more. Either way, the score acts as a key storytelling tool, says John Lunn, the Emmy Award-winning composer who has written for the show since its start. ‘I’m not trying to conjure up an era in the incidental music, although I’m not ignoring it either,’ he explains. ‘It’s not the function of the music. It is to tell the story and also, in a long-running series where people occasionally miss an episode, the music works as a shorthand, emotionally.’

As his music hinges so much on timings, he only works from the finished edit. He has a team helping with the recordings and orchestrating the music, but he writes it alone, improvising on a keyboard as he watches the action. The final versions are performed by a 35-piece orchestra conducted by Lunn at one of London’s iconic music studios: Abbey Road, Angel or Air.

Many themes and motifs recur in various forms. ‘The house has a theme, and there are quite a few themes for relationships, rather than specific people,’ notes Lunn. ‘Anna and Bates get about four or five, as their storyline keeps changing. Then there’s another four or five for Matthew and Mary.’ Even death does not signal an end to those. In Matthew’s absence, Lunn plans to use the music to ‘almost suggest his presence’ in his grieving family’s thoughts.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: