По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

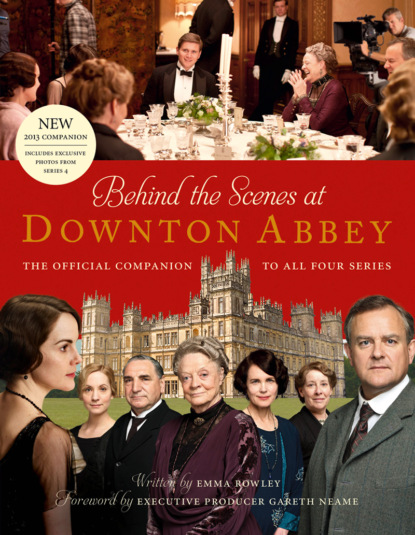

Behind the Scenes at Downton Abbey: The official companion to all four series

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Behind the Scenes at Downton Abbey: The official companion to all four series

Emma Rowley

Gareth Neame

A revealing look backstage at the hit TV show Downton Abbey. In-depth interviews give an exclusive insight into the actors’ experiences on set as well as the celebrated creative team behind the award-winning drama.A lavishly illustrated book full of images from the new series including those stunning 1920s costumes, which will delight the millions of devoted Downton fans. Step inside the props store or the hair and make-up truck and catch a glimpse of the never-before-seen secret backstage world. Expertly crafted with inside knowledge and facts, this book will delve into the inspiration behind the details seen on screen, the choice of locations, the music and much more.With a perspective from the director’s chair and rare insights into filming, this is the inside track on all aspects of the making of the show.

Contents

Cover (#u8c7a501b-f392-5bb5-971e-6052bdab229f)

Title Page (#u653deb27-7db3-599d-8298-b02d6ffdd771)

Foreword by Gareth Neame (#ulink_d07a7934-49a8-515e-99bc-ee307d114185)

Behind the Scripts (#ulink_84b99919-232a-5c47-941f-6b36eb58d971)

Behind the Sets (#litres_trial_promo)

Filming at Highclere Castle (#litres_trial_promo)

Filming at Ealing Studios (#litres_trial_promo)

Filming on Location (#litres_trial_promo)

Inside the Prop Store (#litres_trial_promo)

Inside the Wardrobe (#litres_trial_promo)

Inside Hair & Make-Up (#litres_trial_promo)

Insider Knowledge (#litres_trial_promo)

The Downton Abbey Legacy (#litres_trial_promo)

Series Four Cast List (#litres_trial_promo)

Series Four Crew List (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

FOREWORD (#ulink_38323638-73a1-5819-ad09-49c62e580261)

Gareth Neame (#ulink_38323638-73a1-5819-ad09-49c62e580261)

‘I had seen Gosford Park, the movie that Julian had written so beautifully. I had been incredibly impressed by it. It was not so much the over-arching whodunnit element but just the simple depiction of its world that captured me.’

It was an inauspicious start. As I alighted from my cab outside Drones restaurant in Belgravia (a suitably traditional venue in which to have a working dinner with Julian Fellowes), there he was, hanging about outside, saying, ‘we can’t eat here, their gas is off.’ So began a meandering journey through a London neighbourhood that I suppose the Crawleys might have known well – although of course they were not invented until later that evening. Eventually we found our haven and over a touristic Italian supper I proposed an idea to Julian that became Downton Abbey.

I had long thought that the setting of an English country house during the Edwardian era would make a very suitable arena for an episodic television series. I have often been drawn to cinema for ideas, adjusting and fine-tuning them for television, where in place of the one-off spectacle of the silver screen you have a much larger canvas on which to paint all the characters. Television also offers the joy of repeated pleasure because your audience is able to connect with the characters on a weekly basis. Naturally, some years earlier I had seen Gosford Park, the movie that Julian had written so beautifully for the late Robert Altman. I had been incredibly impressed by it. It was not so much the over-arching whodunnit element but just the simple depiction of its world that captured me. Having worked in British TV drama for a quarter of a century, I was very familiar with maids, footmen and aristocrats, Britain’s extraordinary inventory of historic houses and also our literary inspiration for drama. But when I watched Gosford Park it struck me how I had never entirely believed in the realisation of the setting in its many previous iterations. For once, I felt comfortable in the hands of the filmmakers and I truly appreciated what a fascinating environment I was being transported into. The film stayed in my imagination.

Over dinner Julian and I talked about the DNA of the show – agreeing that it should be equally weighted between the family and its servants. It would have the traditional setting of the Edwardian country house but the density of stories and pace of narrative that is more familiar in a contemporary series. We wanted the show to be something that felt tangible and relevant, so that the audience didn’t so much look back nostalgically but could imagine what it would be like to be, say, Mary changing her attire half a dozen times a day to suit the next leisure activity, or Daisy making two dozen fires before dawn. We selected the years just prior to the First World War as the apogee of the country house and indeed the supremacy of the aristocracy, as much because of the similarities between these characters and ourselves as for the differences. Although their display of rather precise behaviour and manners marks them out as different from us, they have motor cars and electricity, hopes, dreams and ambitions, and are as befuddled by the technology of their age as we are by our latest gadgets from Apple.

Despite our excited and animated conversation about the idea, Julian was initially cautious to revisit the ground he had covered so successfully before (he had, after all, won the Academy Award for his Gosford Park screenplay), I think on the grounds that lightning doesn’t strike twice in the same place. However, some days later I received an email, which over no more than a couple of pages described his initial thoughts on all the major characters who would come to inhabit Downton. The inheritance issue, the lack of a suitable male heir, the distant cousin entering their world for the first time were all there from the off. I had a strong sense that Julian had lived with these characters for many years but was only now describing them on the page. At once the world came alive for me.

Julian and I took the project to Laura Mackie and Sally Haynes at ITV, and with their enthusiastic backing I commissioned Julian to write the first episode. I never forget that his opening stage direction set the premise for Downton Abbey in the most economic, but tantalising, way: The sun is rising behind Downton Abbey, a great and splendid house in a great and splendid park. So secure does it appear, that it seems as if the way of life it represents will last for another thousand years. It won’t. The script was a page-turner and, despite 2009 being a low point as the recession hit the TV industry, Laura and her boss Peter Fincham were so convinced by the material that they ordered the series for production.

Making the first series was a lesson in attention to detail, as we sought to re-enact the style and etiquette of another age and bring to the show the best possible production values that we could. It all went so seamlessly that I became convinced that it was too easy and enjoyable and that the result might end up being a disappointment! After all, so many creative successes have to endure torturous journeys and difficult births. Julian and I had now been joined on the project by our key collaborators, the ‘architects’ of Downton Abbey our producing partners Liz Trubridge and Nigel Marchant, lead director Brian Percival, casting director Jill Trevellick, production designer Donal Woods and costume designer Susannah Buxton.

Alongside Julian’s exquisite scripts was the finest cast of British acting talent we could have assembled. What was so satisfying about it was how Jill appeared to have effortlessly combined much-loved and respected actors such as Dame Maggie Smith, Penelope Wilton, Hugh Bonneville and Jim Carter, with those at the very start of their careers, such as Laura Carmichael and Sophie McShera.

The launch of the show on ITV in September 2010 was a resounding hit and its success was galvanised by a rare spike in ratings for the second episode (very unusually suggesting that all those who sampled the first episode not only came back for more but also brought their friends). Within days of the show’s debut, Downton seemed to enter the vocabulary and become one of those rare pieces of television that leaps out of the TV screen and becomes a part of popular culture.

We were lucky to have Masterpiece (part of PBS) as our US partner, who have done so much to bring British writing and acting to American audiences. The show premiered in the US in January 2011 to unusually high audiences and it was then rolled out across the world where, in territory after territory (we are now in over 200 worldwide) the Crawleys and their servants seemed to grip everyone’s imagination. By the time the second series aired in the UK, with the show recognised as Outstanding Miniseries at the Emmy Awards, it was clear that some sort of global phenomenon was beginning to take shape.

Looking back, it is hard to pinpoint what it was that caused such a sensation. There is seldom only one reason for any creative endeavour of this type to succeed; there can be a multitude of explanations. But I believe a key reason for the success was combining a much-loved, familiar and expressly British genre, that of the English country house, with the pace, energy and accessibility of the most contemporary show.

I also believe that audiences respond to clearly defined ‘precincts’ (this is why police and hospital dramas are enduringly popular around the world) and a precinct is exactly what Downton Abbey is. In every community, human beings organise themselves into hierarchies – in the workplace or at home, we all know our place. We are extremely conscious of these things, irrespective of the country or society in which we live. Nowhere are the peculiarities and eccentricities of social hierarchy more defined than in the British class system of the era we had chosen to depict. So while we all recognise the behaviour, it is a very extreme and exaggerated form of what we have experienced ourselves, and this makes for very compelling drama. Furthermore, Julian’s characters can seldom directly express their mood, feelings or intentions. Almost every scene is subtextual to some degree, and again this really gives the viewer something on which to chew. This is a cast of 20 or so core characters – all of them beautifully written and depicted, irrespective of whether the part is large or small – and because they each keep their own stories running throughout the episodes, they offer unique and individual points of access and appeal to the viewer.

‘Downton is unmistakably a drama series, but thanks to the wit of our screenwriter, directors and actors it is also at times extremely funny.’

The word ‘soap’ has occasionally been applied to the show, and despite some people believing this nomenclature hints at a lesser form of drama, it is not a term that has ever bothered Julian and me. If a soap is defined as a weekly drama with an ensemble of characters cohabiting in a specific environment with their myriad personal stories intertwined, then, dramatically speaking, Downton is a soap. I would suggest it is a soap of cinematic production values and the finest writing and acting, but a soap nonetheless.

For many people worldwide the Crawleys have become an extension of their own families, which explains the anguish that greeted the loss of beloved characters such as William, Sybil and, most recently and most heartbreakingly of all, Matthew. Although, of course, it is the loss of such characters that not only provides the twists and turns which audiences have loved, but also provides the opportunity for us to bring in fresh characters, which in turn replenishes and rejuvenates Downton’s world.

Downton is unmistakably a drama series, but thanks to the wit of our screenwriter, directors and actors it is also at times extremely funny. You wouldn’t describe the show as a comedy, yet humour is so much at the heart of it. Few dramas are as laugh-out-loud funny as Downton is. Of course, much of this dimension is in the charge of Maggie Smith, whose bons mots supplied by Julian and whose character’s disputes with the likes of Isobel or Martha are frankly delicious, and clearly hark back to what some real people must have thought and said not so very long ago. But although it is Violet’s ‘zingers’ that make for the sound bites, there is plenty of comedy going on elsewhere with the rest of the gang (who can forget Molesley’s ham-fisted attempts to woo Anna?).

Finally, and I think perhaps most importantly, we have what may almost have been a happy accident of romance. Back at our inaugural dinner, while I knew that love, marriage and the pursuit of these things would be the backbone of the show, just as it is in real life, I had no idea of the dominant effect that this would have on its fortunes. Romance on screen is decidedly unfashionable. We’re pretty good at depicting sex and relationships, desire and rejection, but there is almost no role for non-sexualised love. This is consistent with us living in an age with a total absence of subtext, where almost anything can be said and there is little time to be anything other than direct. How satisfying it is then, in an era of extremely complex relationships, of text-ing and a wide exposure to sex in almost every part of life, to watch the slow burn and simple unravelling of a good old-fashioned romance. Ironically, starved of such apparently stuffy and staid behaviour, audiences around the world have consumed it hungrily. Fellowes is a master romantic storyteller, but we have also been blessed with the chemistry of Michelle Dockery and Dan Stevens, Jessica Brown Findlay and Allen Leech, and all the others who bring this beguiling element of human nature to life in our show.

It remains to be seen what Downton’s legacy will be. Clearly it has reminded us there is still an appetite for a drama that the whole family can sit down to together, something that aside from Doctor Who was largely thought of as over. Dozens of spoofs, magazine covers, celebrity (and political!) endorsements and fans have emerged. I also believe it has demonstrated that globalisation can touch many forms of entertainment, for while audiences are in some ways becoming increasingly parochial and favouring their own home-grown dramas, those from any country can have worldwide appeal. Audiences in America do not feel that this is a foreign show; they want to spend their time with the Crawleys as much as the Brits do. Subsequent series of Downton have gone from strength to strength, with the growing momentum seemingly most dynamic in the US, where the show is the highest-rating drama ever played on PBS in its illustrious 40-year history. The finale of series three beat the entire competition across all network television.

The launch of the fourth series felt like the right time to produce a companion book about the making of the show, to offer a deeper insight into how it happens. In their own words, the cast of Downton Abbey and our talented crew reveal many of the secrets, previously private experiences and tricks of the trade involved in bringing the show to the screen. It should be a revelatory read for any Downton enthusiast, no matter how much you feel you already know about Britain’s best-known stately home, the family who live there and the servants who work for them.

(#ulink_d5efdedb-60a1-58bb-9804-d581da24f03b)

THE PRODUCERS

Behind the Scripts

‘When I first read the script I couldn’t put it down. I could see each character in my head when I had finished reading. That doesn’t happen very often.’

Hugh Bonneville ROBERT, EARL OF GRANTHAM

The story of Downton Abbey began with a dinner and an idea. The idea quickly became a concept for a television series, which was snapped up by ITV. Gareth Neame commissioned Julian Fellowes to write the first episode, and from the opening scene the script caught the imagination of the TV bosses who read it and recognised that they had something special.

ITV is the show’s natural home, Fellowes believes. There, he and Neame feel they are better able to present the house’s inhabitants as they envisage them, rather than getting mired in the social politics of a century ago, as might be the case at a more ‘interventionist’ rival.

‘For me, the contention that everything was horrible for everyone except for a few rather unpleasant aristocrats is as untrue as saying everything was marvellous for absolutely everyone,’ Fellowes says. ‘The truth, as always, lies somewhere between the two.

Emma Rowley

Gareth Neame

A revealing look backstage at the hit TV show Downton Abbey. In-depth interviews give an exclusive insight into the actors’ experiences on set as well as the celebrated creative team behind the award-winning drama.A lavishly illustrated book full of images from the new series including those stunning 1920s costumes, which will delight the millions of devoted Downton fans. Step inside the props store or the hair and make-up truck and catch a glimpse of the never-before-seen secret backstage world. Expertly crafted with inside knowledge and facts, this book will delve into the inspiration behind the details seen on screen, the choice of locations, the music and much more.With a perspective from the director’s chair and rare insights into filming, this is the inside track on all aspects of the making of the show.

Contents

Cover (#u8c7a501b-f392-5bb5-971e-6052bdab229f)

Title Page (#u653deb27-7db3-599d-8298-b02d6ffdd771)

Foreword by Gareth Neame (#ulink_d07a7934-49a8-515e-99bc-ee307d114185)

Behind the Scripts (#ulink_84b99919-232a-5c47-941f-6b36eb58d971)

Behind the Sets (#litres_trial_promo)

Filming at Highclere Castle (#litres_trial_promo)

Filming at Ealing Studios (#litres_trial_promo)

Filming on Location (#litres_trial_promo)

Inside the Prop Store (#litres_trial_promo)

Inside the Wardrobe (#litres_trial_promo)

Inside Hair & Make-Up (#litres_trial_promo)

Insider Knowledge (#litres_trial_promo)

The Downton Abbey Legacy (#litres_trial_promo)

Series Four Cast List (#litres_trial_promo)

Series Four Crew List (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

FOREWORD (#ulink_38323638-73a1-5819-ad09-49c62e580261)

Gareth Neame (#ulink_38323638-73a1-5819-ad09-49c62e580261)

‘I had seen Gosford Park, the movie that Julian had written so beautifully. I had been incredibly impressed by it. It was not so much the over-arching whodunnit element but just the simple depiction of its world that captured me.’

It was an inauspicious start. As I alighted from my cab outside Drones restaurant in Belgravia (a suitably traditional venue in which to have a working dinner with Julian Fellowes), there he was, hanging about outside, saying, ‘we can’t eat here, their gas is off.’ So began a meandering journey through a London neighbourhood that I suppose the Crawleys might have known well – although of course they were not invented until later that evening. Eventually we found our haven and over a touristic Italian supper I proposed an idea to Julian that became Downton Abbey.

I had long thought that the setting of an English country house during the Edwardian era would make a very suitable arena for an episodic television series. I have often been drawn to cinema for ideas, adjusting and fine-tuning them for television, where in place of the one-off spectacle of the silver screen you have a much larger canvas on which to paint all the characters. Television also offers the joy of repeated pleasure because your audience is able to connect with the characters on a weekly basis. Naturally, some years earlier I had seen Gosford Park, the movie that Julian had written so beautifully for the late Robert Altman. I had been incredibly impressed by it. It was not so much the over-arching whodunnit element but just the simple depiction of its world that captured me. Having worked in British TV drama for a quarter of a century, I was very familiar with maids, footmen and aristocrats, Britain’s extraordinary inventory of historic houses and also our literary inspiration for drama. But when I watched Gosford Park it struck me how I had never entirely believed in the realisation of the setting in its many previous iterations. For once, I felt comfortable in the hands of the filmmakers and I truly appreciated what a fascinating environment I was being transported into. The film stayed in my imagination.

Over dinner Julian and I talked about the DNA of the show – agreeing that it should be equally weighted between the family and its servants. It would have the traditional setting of the Edwardian country house but the density of stories and pace of narrative that is more familiar in a contemporary series. We wanted the show to be something that felt tangible and relevant, so that the audience didn’t so much look back nostalgically but could imagine what it would be like to be, say, Mary changing her attire half a dozen times a day to suit the next leisure activity, or Daisy making two dozen fires before dawn. We selected the years just prior to the First World War as the apogee of the country house and indeed the supremacy of the aristocracy, as much because of the similarities between these characters and ourselves as for the differences. Although their display of rather precise behaviour and manners marks them out as different from us, they have motor cars and electricity, hopes, dreams and ambitions, and are as befuddled by the technology of their age as we are by our latest gadgets from Apple.

Despite our excited and animated conversation about the idea, Julian was initially cautious to revisit the ground he had covered so successfully before (he had, after all, won the Academy Award for his Gosford Park screenplay), I think on the grounds that lightning doesn’t strike twice in the same place. However, some days later I received an email, which over no more than a couple of pages described his initial thoughts on all the major characters who would come to inhabit Downton. The inheritance issue, the lack of a suitable male heir, the distant cousin entering their world for the first time were all there from the off. I had a strong sense that Julian had lived with these characters for many years but was only now describing them on the page. At once the world came alive for me.

Julian and I took the project to Laura Mackie and Sally Haynes at ITV, and with their enthusiastic backing I commissioned Julian to write the first episode. I never forget that his opening stage direction set the premise for Downton Abbey in the most economic, but tantalising, way: The sun is rising behind Downton Abbey, a great and splendid house in a great and splendid park. So secure does it appear, that it seems as if the way of life it represents will last for another thousand years. It won’t. The script was a page-turner and, despite 2009 being a low point as the recession hit the TV industry, Laura and her boss Peter Fincham were so convinced by the material that they ordered the series for production.

Making the first series was a lesson in attention to detail, as we sought to re-enact the style and etiquette of another age and bring to the show the best possible production values that we could. It all went so seamlessly that I became convinced that it was too easy and enjoyable and that the result might end up being a disappointment! After all, so many creative successes have to endure torturous journeys and difficult births. Julian and I had now been joined on the project by our key collaborators, the ‘architects’ of Downton Abbey our producing partners Liz Trubridge and Nigel Marchant, lead director Brian Percival, casting director Jill Trevellick, production designer Donal Woods and costume designer Susannah Buxton.

Alongside Julian’s exquisite scripts was the finest cast of British acting talent we could have assembled. What was so satisfying about it was how Jill appeared to have effortlessly combined much-loved and respected actors such as Dame Maggie Smith, Penelope Wilton, Hugh Bonneville and Jim Carter, with those at the very start of their careers, such as Laura Carmichael and Sophie McShera.

The launch of the show on ITV in September 2010 was a resounding hit and its success was galvanised by a rare spike in ratings for the second episode (very unusually suggesting that all those who sampled the first episode not only came back for more but also brought their friends). Within days of the show’s debut, Downton seemed to enter the vocabulary and become one of those rare pieces of television that leaps out of the TV screen and becomes a part of popular culture.

We were lucky to have Masterpiece (part of PBS) as our US partner, who have done so much to bring British writing and acting to American audiences. The show premiered in the US in January 2011 to unusually high audiences and it was then rolled out across the world where, in territory after territory (we are now in over 200 worldwide) the Crawleys and their servants seemed to grip everyone’s imagination. By the time the second series aired in the UK, with the show recognised as Outstanding Miniseries at the Emmy Awards, it was clear that some sort of global phenomenon was beginning to take shape.

Looking back, it is hard to pinpoint what it was that caused such a sensation. There is seldom only one reason for any creative endeavour of this type to succeed; there can be a multitude of explanations. But I believe a key reason for the success was combining a much-loved, familiar and expressly British genre, that of the English country house, with the pace, energy and accessibility of the most contemporary show.

I also believe that audiences respond to clearly defined ‘precincts’ (this is why police and hospital dramas are enduringly popular around the world) and a precinct is exactly what Downton Abbey is. In every community, human beings organise themselves into hierarchies – in the workplace or at home, we all know our place. We are extremely conscious of these things, irrespective of the country or society in which we live. Nowhere are the peculiarities and eccentricities of social hierarchy more defined than in the British class system of the era we had chosen to depict. So while we all recognise the behaviour, it is a very extreme and exaggerated form of what we have experienced ourselves, and this makes for very compelling drama. Furthermore, Julian’s characters can seldom directly express their mood, feelings or intentions. Almost every scene is subtextual to some degree, and again this really gives the viewer something on which to chew. This is a cast of 20 or so core characters – all of them beautifully written and depicted, irrespective of whether the part is large or small – and because they each keep their own stories running throughout the episodes, they offer unique and individual points of access and appeal to the viewer.

‘Downton is unmistakably a drama series, but thanks to the wit of our screenwriter, directors and actors it is also at times extremely funny.’

The word ‘soap’ has occasionally been applied to the show, and despite some people believing this nomenclature hints at a lesser form of drama, it is not a term that has ever bothered Julian and me. If a soap is defined as a weekly drama with an ensemble of characters cohabiting in a specific environment with their myriad personal stories intertwined, then, dramatically speaking, Downton is a soap. I would suggest it is a soap of cinematic production values and the finest writing and acting, but a soap nonetheless.

For many people worldwide the Crawleys have become an extension of their own families, which explains the anguish that greeted the loss of beloved characters such as William, Sybil and, most recently and most heartbreakingly of all, Matthew. Although, of course, it is the loss of such characters that not only provides the twists and turns which audiences have loved, but also provides the opportunity for us to bring in fresh characters, which in turn replenishes and rejuvenates Downton’s world.

Downton is unmistakably a drama series, but thanks to the wit of our screenwriter, directors and actors it is also at times extremely funny. You wouldn’t describe the show as a comedy, yet humour is so much at the heart of it. Few dramas are as laugh-out-loud funny as Downton is. Of course, much of this dimension is in the charge of Maggie Smith, whose bons mots supplied by Julian and whose character’s disputes with the likes of Isobel or Martha are frankly delicious, and clearly hark back to what some real people must have thought and said not so very long ago. But although it is Violet’s ‘zingers’ that make for the sound bites, there is plenty of comedy going on elsewhere with the rest of the gang (who can forget Molesley’s ham-fisted attempts to woo Anna?).

Finally, and I think perhaps most importantly, we have what may almost have been a happy accident of romance. Back at our inaugural dinner, while I knew that love, marriage and the pursuit of these things would be the backbone of the show, just as it is in real life, I had no idea of the dominant effect that this would have on its fortunes. Romance on screen is decidedly unfashionable. We’re pretty good at depicting sex and relationships, desire and rejection, but there is almost no role for non-sexualised love. This is consistent with us living in an age with a total absence of subtext, where almost anything can be said and there is little time to be anything other than direct. How satisfying it is then, in an era of extremely complex relationships, of text-ing and a wide exposure to sex in almost every part of life, to watch the slow burn and simple unravelling of a good old-fashioned romance. Ironically, starved of such apparently stuffy and staid behaviour, audiences around the world have consumed it hungrily. Fellowes is a master romantic storyteller, but we have also been blessed with the chemistry of Michelle Dockery and Dan Stevens, Jessica Brown Findlay and Allen Leech, and all the others who bring this beguiling element of human nature to life in our show.

It remains to be seen what Downton’s legacy will be. Clearly it has reminded us there is still an appetite for a drama that the whole family can sit down to together, something that aside from Doctor Who was largely thought of as over. Dozens of spoofs, magazine covers, celebrity (and political!) endorsements and fans have emerged. I also believe it has demonstrated that globalisation can touch many forms of entertainment, for while audiences are in some ways becoming increasingly parochial and favouring their own home-grown dramas, those from any country can have worldwide appeal. Audiences in America do not feel that this is a foreign show; they want to spend their time with the Crawleys as much as the Brits do. Subsequent series of Downton have gone from strength to strength, with the growing momentum seemingly most dynamic in the US, where the show is the highest-rating drama ever played on PBS in its illustrious 40-year history. The finale of series three beat the entire competition across all network television.

The launch of the fourth series felt like the right time to produce a companion book about the making of the show, to offer a deeper insight into how it happens. In their own words, the cast of Downton Abbey and our talented crew reveal many of the secrets, previously private experiences and tricks of the trade involved in bringing the show to the screen. It should be a revelatory read for any Downton enthusiast, no matter how much you feel you already know about Britain’s best-known stately home, the family who live there and the servants who work for them.

(#ulink_d5efdedb-60a1-58bb-9804-d581da24f03b)

THE PRODUCERS

Behind the Scripts

‘When I first read the script I couldn’t put it down. I could see each character in my head when I had finished reading. That doesn’t happen very often.’

Hugh Bonneville ROBERT, EARL OF GRANTHAM

The story of Downton Abbey began with a dinner and an idea. The idea quickly became a concept for a television series, which was snapped up by ITV. Gareth Neame commissioned Julian Fellowes to write the first episode, and from the opening scene the script caught the imagination of the TV bosses who read it and recognised that they had something special.

ITV is the show’s natural home, Fellowes believes. There, he and Neame feel they are better able to present the house’s inhabitants as they envisage them, rather than getting mired in the social politics of a century ago, as might be the case at a more ‘interventionist’ rival.

‘For me, the contention that everything was horrible for everyone except for a few rather unpleasant aristocrats is as untrue as saying everything was marvellous for absolutely everyone,’ Fellowes says. ‘The truth, as always, lies somewhere between the two.