По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

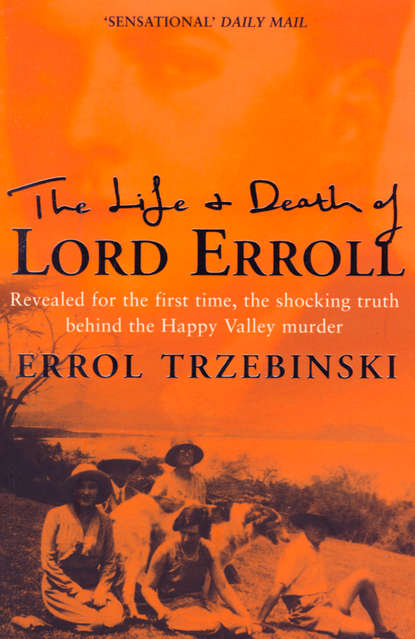

The Life and Death of Lord Erroll: The Truth Behind the Happy Valley Murder

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Joss was an experienced traveller in Europe, but nothing would have prepared him for the scenes in Mombasa’s old town. Its narrow streets were peopled with many different races. Women veiled in black purdah strolled among near-naked non-Muslim women, moving nonchalantly along in the heat with their unevenly shaped loads – such as bunches of green bananas or even a bottle – balanced perfectly on their heads. Commerce was noisy, shouted in many tongues as locals haggled for business; government officials, turbaned Sikhs and Indian dukawallahs

(#litres_trial_promo) seemed oblivious to the stench of fish and shark oil hanging on the air. In MacKinnon Square, another Union Jack hung limply from its flagpole above the District Commissioner’s office with its rusting corrugated-iron roof. Feathery coconut palms, blue sea and sky gave a feeling of infinite peace, yet Fort Jesus and the cannon standing resolutely beneath its low walls spoke of a history of bloodshed and strife.

The Hays spent one night at Mombasa Club, dining under the moon on its terrace, sleeping under nets as protection against mosquitoes; translucent geckos about the length of a finger darted about the walls, consuming the insects. One train per day left for Nairobi at noon, and the three-hundred-odd mile crawl on the single narrow-gauge track up country began, taking about twenty-four hours.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘Penniless, dashing, titled and an accomplished sportsman’, as he was described in a newspaper profile a decade after his arrival in the colony, Joss would now make Kenya his home.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Kenya would suit him because he was not afraid of the unexpected. Africa is nature’s Pandora’s box and the gambler in Joss would respond to its uncertainties. Idina loved everything about the colony too; she ‘could muster wholesome fury against those who she thought were trying to damage the land of her adoption’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Her instinct that Joss would share her enthusiasm and strong feelings had been right. Life in the colony demanded hard work, rough living and life-threatening risks, but for an adventurer like Joss, who had all the right contacts and, thanks to Idina, plenty of money, Kenya offered the promise of the Imperial dream fulfilled. In addition, Joss had an open, inquiring mind and a willingness to seek advice from those more experienced than he was.

The Uganda Railway, by which the couple travelled to their new marital home, had been completed in 1901. The Maasai called it the ‘iron snake’ and those who opposed it the ‘lunatic line’. It ended at Port Florence (later called Kisumu) on Lake Victoria, and was a formidable achievement that took five years to complete, traversed wilderness and cost a staggering £5,500,000 without a jot of evidence to justify the expense. The Foreign Office, adept at muddling through, had then enticed out white settlers with cheap land flanking the railway-line.

Joss and Idina journeyed on the train from Mombasa in square compartments, nicknamed ‘loose-boxes’ – there were no corridors – and the train jolted ceaselessly while on the move, stopping, only for meals, at a series of Indian dak-bungalows. These breaks were refreshing on a long journey, which could be drawn out further if elephant or rhino blocked the line. Choking red dust coated every passenger. Any attempt while the train was at a standstill to remove the wire screens at the windows to get more air was met by a scolding from the invariably Goan stationmaster: ‘Bwana! Mosquito bad, Bwana. Malaria bad.’ The first stop at Samburu for tea was accompanied by toast and rhubarb jam. Menus were always the same.

Dinner was taken at Voi, where large hanging lamps like those suspended over billiard tables were bombarded by insects, dudus, which bounced off to lodge themselves in the butter or the lentil soup. The fish was smothered in tomato sauce to disguise its lack of freshness, and followed by beef or mutton, always curried, for the same reason. Lukewarm fruit salad or blancmange rounded off the meal, with coffee.

(#litres_trial_promo) Stewards made up bunks for the night with starched sheets, pillows and blankets, and in the dark, as the train rattled onward and upward, occasionally a cry would intrude in the night: ‘All out for Tsavo!’ Joss could mimic the sing-song Goan accent perfectly.

(#litres_trial_promo) At dawn everyone clambered on to the line to stretch their legs. Hot shaving water would materialise in jugs, produced from the steam by the engine driver and delivered with the morning tea by waiters in white uniform and red fezzes. Breakfast was taken further up the line at Makindu.

(#litres_trial_promo)

As the journey progressed, Joss shared the excitement felt by every pioneer: at the spectacle of Kilimanjaro under its mantle of snow at sunset; at the endless scrub and the trickles of water optimistically called rivers; then disbelief, on the final approach to Nairobi, at the sheer dimensions of the Athi Plains, where mile upon mile of grassland teemed with gazelle, rhino and ostrich, and herds of giraffe, zebra and wildebeest roamed wild against the deep-blue frieze of the Ngong Hills. Seeing creatures in their natural habitat instead of behind bars was like rediscovering the Garden of Eden. And finally, beyond Nairobi, awed silence at the spectacle of the Great Rift Valley.

When Joss first laid eyes on Nairobi in 1924 it had become something akin to a Wild West frontier town patched together with corrugated iron. Windswept and treeless a quarter-century earlier, it had been unsafe after dark ‘on account of the game pits dug by natives’. Her Majesty’s Commissioner for British East Africa, Sir Charles Eliot, had embarked on a policy of attracting white settlers. When the European population amounted to 550 it was decided to build a town hall. All around was evidence of plague, malaria and typhoid as the shanty-town grew. These same diseases were still a life-threatening problem in Nairobi’s bazaar in Joss’s and Idina’s day.

By 1924, Nairobi had become a melting-pot, with settlers from all over the world bringing their different ways to the colony – their languages, their recipes, their religions, morals and social customs. Joss was no stranger to foreign languages, and before long Swahili would encroach too on his conversation: shaurie for ‘problem’; chai for ‘tea’; dudu for any form of insect life from a safari ant to a black widow spider; and barua for ‘note’ – important when there were no telephones by which to communicate. Sometimes English words with no Swahili equivalents were adopted into the language by the addition of an ‘i’ – bisikili, petroli. Indian words seasoned the mélange: syce for ‘groom’, gharrie for ‘motor-car’, dhersie for ‘tailor’. Settlers developed a local pidgin Swahili of their own, known by natives as Kisettla. When the settlers began conversing in Kisettla, notice was being given that all convention was henceforth left ‘at home’.

Beyond Nairobi the Uganda Railway traversed escarpment and volcanic ridges along the Rift Valley, with its lakes scattered like pearls; and further north, at Timboroa, the line rose to almost 8,000 feet in a stupendous feat of engineering, scaling ravines and descending again until it halted abruptly above the next large expanse of water, Lake Victoria, in Nyanza. At the railhead at Kisumu, the main crops were bananas and millet. There was still talk at the local bridge tables, of missionaries in the area who had disappeared, thanks to cannibals.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Joss and Idina got off the train at Gilgil, about three-quarters of the way along the Uganda railway-line. A tiny dot, hardly on the map, Gilgil was so small that it boasted only a railway-siding, but it provided a vital link with Nairobi as travel by car was barely feasible because of the appalling state of the roads. The Wanjohi Valley was tucked away in the hills behind Gilgil. This broad and undulating virgin territory, where yellow-flowering hypericum bushes grew in profusion, was watered by two rivers. The Wanjohi and the Ketai, flanked by beautiful podocarpus, ran more or less parallel and fed many icy, turbulent, gravel-filled streams, crisscrossing the valley. Ewart Scott Grogan, a pioneer settler who played an important role in the development of Kenya, had stocked these with fingerlings in 1906 – brown as well as rainbow trout. As one left the valley going uphill to ‘Bloody Corner’, so called because so many vehicles got stuck in the mud there, the Wanjohi changed its name to the Melewa. Fed by the Ketai, it flowed down towards Gilgil, ‘through the plains and past an abandoned factory and former flax lands, through dust and mud, over rocks and stones, to Naivasha, the lake thirty miles away’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Joss’s and Idina’s new home, Slains, was situated just eighteen miles north-east of Gilgil. On arriving at the railway-siding they were met by their farm manager, Mr Pidcock, who drove them the forty-five-minute journey to the farmhouse. Slains nestled at one end of a private two-mile murram track leading in the opposite direction from Sir John ‘Chops’ Ramsden’s seventy-thousand-acre Kipipiri Estate and his home, Kipipiri House. Slains was a rambling, charming farmhouse, low-lying and beamed, with a corrugated-iron roof, open ceilings, verandas and long bedroom wings. The kitchen, as usual in Kenya, was housed separately. The rooms were vast with partitioned walls which allowed sound to travel freely, affording little privacy.

In Kenya, this style of housing, reminiscent of Provençal dwellings, was the inspiration of Chops Ramsden and unique to the district. The houses were constructed by a builder from Norfolk whom Ramsden, a hugely wealthy landowner, had initially brought to Kenya to construct Kipipiri House. This had pleased him so much that the builder stayed on and was employed to build every additional manager’s house and the neighbours’ homes as well. Before leaving for Kenya, Idina had asked Chops Ramsden to supervise the construction of Slains ready for her and Joss’s arrival. The uniformity of the Wanjohi Valley settlers’ houses reinforced the club-like atmosphere of the area.

Slains’ setting was as dramatic as its namesake in Scotland. The early-morning mists that swamped this moorland wilderness were damp enough to warrant the wearing of wellington boots. At sundown, a chill would come into the air, making night fires a necessity. Yet by day its climate was that of a perfect English summer. The equatorial sun at an altitude of 8,500 feet produced an exuberance of growth. Looking out from the front of Slains towards Ol Bolossat, which was more often a swamp than a lake, except when it was fed during the rains by the Narok River, occasionally one could see the gleaming water flowing over a two-hundred-foot shelf at Thomson’s Falls. In the distance up the valley behind the house rose the mountain Kipipiri, which joined the Aberdare range. The cedar-clad forest ridge which ran along the valley, dubbed by Frédéric de Janzé ‘the vertical land’, dwarfed everything below, and this haunt of elephant and buffalo lent grandeur to the simplicity of daily existence.

For life in Kenya in 1924 was far from an unbroken idyll. Joss was joining a community of pioneers who were still trying to redress the effects of their absence from their farms during the First World War. These early settlers might have picked up land at bargain prices but there had been a catch: every decision affecting their livelihood was made in London. Land for farms had in the early years of the twentieth century been parcelled out under ninety-nine-year leases ‘with periodic revision of rent and reversion to the Crown with compensation for improvements’, which meant that the settlers would forfeit everything unless they developed the property to prefixed standards.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Only a few months before Joss first arrived at Slains, the Duke of Devonshire, then Colonial Secretary, had put the wind up European settlers in Kenya by declaring that ‘primarily Kenya is African territory’, and reminding them that His Majesty’s Government would pursue the ‘paramountcy of native interests’; furthermore, ‘if the interests of the immigrant races should conflict, the former should prevail’.

(#litres_trial_promo) While this meant little to Joss in 1924, he would become a champion of the European settlers’ interests in due course.

In 1920 Sir Edward Northey, the Governor, had made seven major innovations. Firstly, in that year the Protectorate graduated to Crown Colony. Secondly, a new Legislative Council was set up to represent the settler and commercial interests, and European settlers were granted the vote. The colony’s affairs could now be debated in the local parliament, ‘though it was stressed that the colony was still to be ruled from Whitehall’.

(#litres_trial_promo) In due course Joss became a member of ‘Legco’, as it was known. Thirdly, the railway was reorganised; its finances were separated from those of the Protectorate and the railway system was placed on a business footing. Four, under the control of an intercolonial council, the first big loan was raised for a new branch railway. Joss would see its construction, as well as the harbour works, begun and completed. Five, the Civil Service was reshaped. The rates of pay were raised to put them on a level with other colonial services. Six, the budget was balanced and inflated expenditure was cut drastically ‘so as to bring the country’s coat within measure of its cloth’.

(#litres_trial_promo) These innovations formed the framework of the political structure within which Joss would move and be affected as a settler.

Finally, it was under Northey that the Soldier Settlement Scheme was launched. In spite of setbacks, this was acknowledged to be the most successful postwar settlement project in the Empire. And – through Idina’s ex-husband, Charles Gordon – Joss benefited from the Government’s second attempt since the building of the Uganda Railway to fill the empty land with potential taxpayers and producers of wealth. These ex-soldiers got their land on easy terms, and Charles Gordon had been one of many applicants. Sir Delves Broughton, too, had drawn soldier settlement land, coming out initially in 1919 to inspect it. Allocation tickets could be bought in Nairobi and at the Colonial Office in London. ‘By June 1919 more than two thousand applications had flooded into Nairobi to take their chance at a grand draw held on the stage of the Theatre Royal.’ Like a lottery, the tickets were placed in barrels to decide who was to get what. ‘It took two revolving drums all day to distribute the empty acres by lottery to an audience of nail-biting would-be farmers.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

One of the first settlers in Kenya, Hugh Cholmondeley, 3rd Baron Delamere, had trekked on foot into Kenya in 1897 with camels from Somalia, arriving with a doctor, a photographer and a taxidermist. Africa infected him with its potential. In 1903, Delamere applied for land in British East Africa on the ninety-nine-year-lease scheme and was granted a total of a hundred thousand acres at Elmenteita near Gilgil and at Njoro beyond Nakuru; he called his first home Equator Ranch. Njoro was already regarded as the cradle of European settlement by the time Joss and Idina arrived in Kenya. While D, as everyone called him, was not the first to take up land, he became the most influential of all the settlers. He was to have a powerful influence on Joss – they were virtually neighbours – and gradually Joss would find himself drawn into local politics. D’Abernon had taught Joss about the Scramble for Africa, and so he knew more than most neophyte settlers about the political machinations with foreign Imperial powers that had gone before. Joss and D, both Old Etonians, were utterly different types who stood for quite different things, but they were united in their love of Kenya and a willingness to use all possible means for their cause.

D was the leading light among the settler community. When not working his farms, he headed deputations to Government House, even taking a delegation to London in early 1923 to fight the settlers’ cause with a Government now much less in favour of colonialist expansion. He also found time to sit beside his own hearth with several Maasai who had walked for miles to chat with him at Soysambu

(#litres_trial_promo) wearing only a shuka and beads. Gilbert Colvile and Boy Long, D’s former manager – the other two in the colony’s great trio of cattle barons – would also often consort with the Maasai, who were greatly respected for their knowledge of cattle-breeding.

Gilbert Colvile was a highly eccentric character, almost a recluse. His mother Lady Colvile ran the Gilgil Hotel with her maid.

(#litres_trial_promo) The hotel was something of a focal point for European settlers, who would regularly call upon Lady Colvile. Her son would later get to know Joss when Joss moved to Naivasha. Colvile became one of the most successful cattle barons in Kenya, doing a great deal to improve Boran cattle by selective breeding. He had been at Eton with Delves Broughton and Lord Francis Scott. The latter, like Broughton, whose commanding officer he had been during the Great War, had drawn land from the 1919 Soldier Settlement Scheme. Scott was chosen to replace Delamere as Leader of the Elected Members of Legislative Council and as their representative to London after D’s death in 1931.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Once Joss and Idina had settled in, the rhythm of life at Slains was orderly and as balmy as the daytime temperature. Their prelude to each day was a glorious early-morning ride. Their horses would be groomed and saddled, waiting for them to mount. Before the dew was burnt off the grass by the sun, they would ride out for miles over the soft, turf-like vegetation that rose up as if to meet the sky. The muffled thud of hooves would send warthog scurrying and the needle-horned dik-dik bounding away in pairs. Ant-bear holes were a hazard for their sure-footed Somali ponies, as the scent of bruised wild herbs rose from warm, unbroken soil under their unshod hooves in their jog home afterwards. Joss would change into a kilt and then breakfast on porridge and cream.

Labour was cheap after the war, but not readily forthcoming. District Commissioners had applied to the local chiefs to exert ‘every possible persuasion to young men to work on the farms’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Every servant needed training from scratch – most candidates had never set foot in a European household before. Appointing a major-domo was a complete lottery. The Hays had two Europeans on their staff, one of whom was Marie, a French maid who would become integral to Idina’s households. At times of crisis, Marie could be heard throughout the house ‘wringing her fat little hands, her voice rising higher and higher, “Cette affreuse Afrique! Cette affreuse Afrique!”, her high heels tapping out her progress on the parquet floors as she sought out Lady Hay with the latest disaster’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Then there was Mr Pidcock, their farm manager, who also ran the Slains dairy.

Butter-making was done early in the morning or late in the evening; the butter was washed in the clear river water, which gave it its wonderful texture. Every other day it would make its way to Gilgil by ox-cart, wrapped in a sheet torn from the Tatler.

(#litres_trial_promo) The Slains cuisine would never want for supplies of farm produce and, thanks to a good kitchen garden, the table there was superb. Idina’s menus were sophisticated, and Marie taught the African cook how to make soufflés and coq au vin on a blackened Dover stove fuelled by kuni.

(#litres_trial_promo) The ring of the axe was a familiar sound since wood heated the water for baths.

Waweru, Joss’s Kikuyu servant, came to work for him in 1925 as a ‘personal boy’ and may well have started life as a kitchen toto, when Joss spotted his potential. He was only a little younger than Joss – the Africans kept no precise record of the year they were born – and had never been to school. He would work for Bwana Hay until Joss’s death, and was utterly dependable. By the time he was called as a witness during the murder trial in 1941 as ‘Lord Erroll’s native valet’ this Kikuyu man had been privy to many intimacies in Joss’s life. Eventually promoted to major-domo at Joss’s next home, Waweru ran the household very capably, performing his duties with all the expertise and dignity of a seasoned English butler, making callers welcome in Joss’s absence, arranging flowers and overseeing junior staff.

(#litres_trial_promo) Waweru’s opinion of Joss as a ‘good man’ made an impression in court during the trial, and certainly debunks the rumour spread after Joss’s death that he mistreated his staff.

(#litres_trial_promo) At Slains, the African servants were given presents on Boxing Day, amid much celebration. As Joss once explained, one had to ‘budget on the basis of two to three wives, and half a dozen children per wife per family’. Nevertheless, everyone received presents.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Another inaccurate assessment of Joss was the assumption that, because he was rich and titled, he was nothing but a ‘veranda farmer’. He certainly enjoyed life and drove around the area dangerously fast in Idina’s Hispano-Suiza with its silver stork flying over the crest of its great bonnet. His hair-raising driving earned him his Swahili name, Bwana Vumbi Mingi Sana, meaning ‘a lot of dust’. For all his high-spirited behaviour, though, Joss was serious about farming. The Hays were the first settlers to breed high-grade Guernsey cattle in Kenya, for example. And thanks to advisers such as Boy Long and Delamere, they were able to avoid the most common blunders made by newcomers, such as putting very large bulls to native heifers, which would result in calving difficulties. The pioneers had learned the hard way. Once the conformation problem was recognised, half-bred bulls were used instead and heifers fared better.