По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

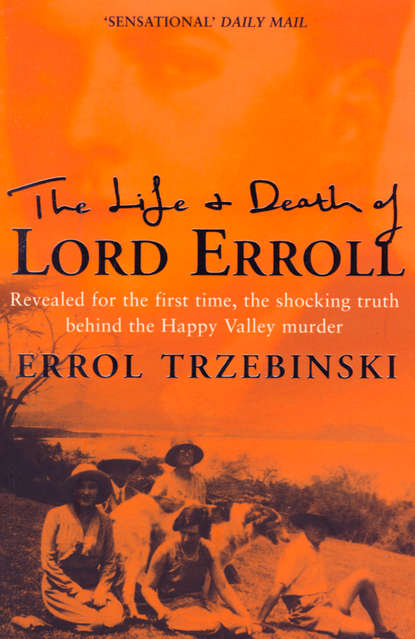

The Life and Death of Lord Erroll: The Truth Behind the Happy Valley Murder

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

(#litres_trial_promo) St Andrew’s Day and the Harrow match became too poignant reminders of happier times. Rather than providing such gaiety as they would have done in peacetime, they cast long shadows over tradition. As the obituaries of Old Etonians increased as the war progressed, rationing tightened and it became a point of patriotic honour and discipline that the boys should eat all their food, without comment or complaint, however unpalatable it sometimes seemed. This may be why Joss never questioned the meal put in front of him. He enjoyed haute cuisine but he could live without such luxuries; he always entertained well, but without ostentation. Since food was greatly restricted, when the growing boys were ravenous their supplies were now mostly supplemented by tinned sardines and caramels from Fortnum and Mason’s.

(#litres_trial_promo) The shortage of fuel meant that fires were few and far between in the cold months, so that the normal rigours of school life were accentuated. In addition, a pall of gloom was evident on every page of the Eton Chronicle – hardly surprising – with a grim, industrialised war raging as the world had never before known it. By the second issue of the Michaelmas half, a list of forty fallen was published under the heading ‘Etona Non Immemor’:

(#ulink_a3cac76a-5faa-54b1-93b6-08c297356c85) when the challenge had come, Etonians, like so many young men all over England, had responded and enlisted. The life of the college was profoundly affected by so many unexpected leavers, including nine masters. Some masters were even recalled from service to step into the breach. None could forget that Eton was in the grip of the war. Every home was saddened by losses among the generation of boys above Joss. Poetic epitaphs appeared in Latin or Greek, as well as in English.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The effect on Joss was to be lasting. He would never be able to fathom the eagerness of the young men to reach the front line – over the first five days of the war 10,626 men had enlisted. All Joss could see, at barely thirteen years old, was the meaningless waste of young and healthy lives. In the Chronicle it was not uncommon for a letter from a friend to appear, or a brief obituary by a tutor, speaking of the ‘cheerfulness’ with which some young officer had died.

During the summer half of 1915 Hubert and Joss began a lifelong passion for bridge when they started playing Pelmanism, a card game demanding, as does bridge, an excellent memory and great concentration. The deck would be scattered face down on the lawn. At each turn, the player turns over two cards, but to score a trick the upturned cards must match. Joss’s success in pairing cards off was almost impossible for Hubert to beat,

(#litres_trial_promo) his perfect recall on the lawns of Eton is early confirmation of his ‘photographic’ memory. The two boys also shared an interest in drama. Joss’s forte was reciting from Don Quixote and Thackeray’s Esmond at ‘speeches’. His ability to take in everything at a glance gave his parodies an accuracy that could be quite cutting. His performances for friends were spontaneous, broken up with snatches of German, gesturing, accenting, mimicking hysterical Italians or one of the pompous ‘Danish Schleswig-Holstein Sonderberburg Glucksburgs’, or fussing about in farcical parody of one of his mother’s Austrian maids.

(#litres_trial_promo) Joss took a delight in playing the buffoon. Making capital out of his surname, he would imitate a yokel, with bits of straw in his hair, using such phrases as ‘Neither Hay nor grass’, ‘Making Hay while the sun shines’ and ‘Hey nonny-no’. If his repartee was sometimes too quick for the slow-witted, puns such as ‘a roll in the Hay’ and ‘Haycock’ never missed the mark and could be relied upon to raise a lot of sniggering.

(#litres_trial_promo) Victor Perowne, editor of the Eton Chronicle, allegedly composed several poems and pieces of prose about ‘Haystacks’ for the Chronicle, although none can be found today so possibly these jottings were private. Perowne eventually became Ambassador to the Holy See. At Eton, according to Sacheverell Sitwell, Perowne had fallen for Joss ‘hook, line and sinker’. Sitwell was never able to see Joss’s appeal yet he spoke of his magnetism, witnessing him ‘more than once, followed down Keate’s Lane by a whole mob of boys’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Joss’s academic progress is impossible to assess, as copies of school reports were not made at Eton in those days.

(#litres_trial_promo) Other sources show that in 1916 he was a ‘dry bob’ (he played cricket rather than rowed in the summer term) and was ‘very keen on football, being one of the first to play the Association game at the school’.

(#litres_trial_promo) He also participated in the Lower Boy House Cup, ‘Ante Finals’, ‘J. V. Hay playing in De Havilland’s team for the Field Game when he was in the 28th Division’ (Hubert Buxton was in the twenty-seventh).

(#litres_trial_promo) However, cricket and cards were but minor pastimes that summer of 1916 compared to Joss’s discovery of sex.

There was a lot of talk about Joss being ‘very much AC/DC’ while at Eton.

(#litres_trial_promo) These rumours were strongly denied by his brother Gilbert and his son-in-law Sir Iain Moncreiffe. By 1916 Joss had already been a member of the Eton College Officer Training Corps for a year, where apparently there were always ‘a lot of tents heaving on the job. One young and popular boy charged £3.00 per go.’ At school he was great friends with Fabian Wallis, who was then openly homosexual, a friendship that resumed in Kenya.

(#litres_trial_promo) Flirting with the boys down Keate’s Lane does demonstrate his tendency at least outwardly to defy sexual conventions. He was of course attractive to women, but even those who had slept with him described him as ‘a pretty-looking man’, accepting that he might have been bisexual. As one admirer put it, ‘Etonians had a certain reputation. There was something feminine about Joss, which one could not ignore.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Joss’s initiation into heterosexual sex began at fifteen: in the Michaelmas half of 1916 he was caught in flagrante delicto with a maid, a woman old enough to be his mother. He had obviously confided in his great friend Hubert Buxton, but naturally the latter never elaborated beyond the fact that ‘Joss had been sent down for being a very naughty boy indeed’; he added wistfully that Joss had been ‘so attractive and so smart’, implying that he only wished that he too had had the guts and ingenuity to get himself into bed with a woman at so tender an age.

(#litres_trial_promo)

If his peers admired his seduction skills, the authorities at Eton did not. Usual punishment procedure was followed while the decision to ‘sack’ (expel) Joss was being made. While routine offences were dealt with in the headmaster’s and lower master’s ‘bill’, and floggings were recorded in a book open only to masters, more serious matters such as stealing or sexual misdemeanours were noted in separate confidential books. Because Joss’s offence was sexual and therefore considered to be serious, the beating was to be carried out in private. A praepostor (a senior boy) extracted Joss from class. Ritual prevailed.

‘Is there a Mr Hay in the Division?’

‘There is.’

‘He is to report to the head master in lower school after 12.’

Did Joss blanch? Probably not. It was not in his nature. Nor was it in his nature to blush. Just after Lupton’s Tower chimed midday, two praepostors accompanied ‘Mr Hay’ from the twenty-eighth division to the headmaster Dr Edward Lyttleton’s schoolroom; Lyttleton had found homosexuality so prevalent in 1915 that he had denounced the practice openly. (He left Eton soon after Joss.)

(#litres_trial_promo) Dressed in a clergyman’s cassock and accompanied by the head porter, carrying a birch rod in solemn procession, Lyttleton now ordered Joss to take down his trousers and underwear and to bend over the flogging block. After reciting his offence and outlining his punishment, six strokes of the birch rod, complete with twigs and leaves, were administered. It was bad form to cry. After Joss rose from the flogging block, Lyttleton presented him with the object that had given him his painfully wealed skin.

(#litres_trial_promo)

We do not know if Joss’s parents hastened back from Le Havre to England on account of his dismissal. As a result of his fall from grace, however, poor Gilbert’s name was withdrawn from Eton. He was educated at Cheltenham College and Cambridge instead.

Quite apart from the thorough disgrace Joss would have been made to feel over his dismissal from Eton, he had already endured a rotten few months before being caught with the maid. Worsening an already insecure situation for Joss and his siblings, Slains, along with Longhaven House which belonged to its estate – Joss’s rightful inheritance – had been sold off to Sir John Reeves Ellerman, who would dispose of these dwellings without even occupying them, a callous blow to the Erroll family.

(#litres_trial_promo) Eliza Gore, their great-grandmother, also died that year in the Royal Cottage at Kew, leaving only Sir Francis Grant’s painting as a reminder of her spirit and of the adventures that her descendants had heard from her own lips. Grant’s portrait has her standing by her grey Arab pony, a gift from the Sultan of Turkey, ever reminding them that on this steed Eliza Gore had followed her husband without complaint throughout the Crimean campaign.

(#litres_trial_promo)

With Eliza Gore’s passing and the loss of Slains, all in one swoop Joss’s childhood had disappeared. The ruins of both Old and New Slains still stand today, there to be looked upon by his great-grandchildren even though fierce winds have torn away the last traces of plaster. They can hear the same cries from sea-birds, the echoes of gulls and puffins, swooping and screaming through the castles’ once proud corridors.

* (#ulink_28fb693d-2240-5513-97eb-9ca1a9d45f69)Plant badges were symbols used to distinguish clans.

* (#ulink_339a9a58-7960-5002-86a2-d77656efc8e3)Later the Duke of Portland.

* (#ulink_21637263-ed26-5568-aa75-de4929bcdc73)Eton does not forget.

4 To Hell with Husbands (#ulink_1586425b-f6e8-5917-81db-ebf124ac0d82)

‘Come, come,’ said Tom’s father, ‘at your time of life,

There’s no longer excuse for thus playing the rake –

It is time you should think, boy, of taking a wife’ –

‘Why, so it is, father – whose wife shall I take?’

Thomas Moore

Whereas a weaker young man might have been unable to recover from the shame of having been removed from one of England’s finest schools, Joss’s disgrace appears to have had no effect on his confidence.

(#litres_trial_promo) If his parents were livid with him, they did not let it show publicly. They allowed his education to continue at home in Le Havre, the British Legation to Brussels’ wartime base. Lord Kilmarnock found a tutor for him, a man who before the war had worked at the University of Leipzig. Through him Joss brushed up his German, and according to fluent German-speakers he spoke the language extremely well, some even claimed ‘beautifully’.

(#litres_trial_promo) (In later life, without daily practice, his command of German weakened somewhat.) His French also benefited from his return to a francophone country.

In a press interview in the 1930s Joss said of his time in Le Havre, vaguely, that he had been ‘performing liaison work with the Belgians’. Perhaps his father had pulled strings to get him some practical experience of Foreign Office work and to broaden the narrow horizons of his studies at home. When Lord Kilmarnock moved on after the war Joss too was transferred to the British Legation in Copenhagen as an honorary attaché. Lord Kilmarnock acted as Chargé d’Affaires there until August 1919.

(#litres_trial_promo) Joss was eighteen by this time and, help from his father or no, he was beginning to gain some very valuable Foreign Office experience.

Meanwhile, Lord Kilmarnock was made a CMG in June 1919 and a Counsellor of Embassy in the diplomatic service three months later. His father’s impressive career was starting to awaken ambitions in Joss, for that same year he applied to sit the Foreign Office exam in London. Candidates were told to bring a protractor with them.

(#ulink_1cacc5a9-915d-5208-b3e3-73a3aa646342) The result of this strange instruction was that on the morning of the exam, outside Burlington House, ‘a multitude of officers converged with protractors in their hands’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Since Joss had ‘one of the best brains of his time’ he sailed through his Foreign Office examination – no mean achievement. At the time the Foreign Office exam was considered to be ‘the top examination of all’. The Kilmarnocks must have been very relieved that their son appeared to be looking to his laurels at last. On the strength of his exam results Joss was given a posting, on 18 January 1920, as Private Secretary to HM Ambassador to Berlin for three years – ‘a critical post at a critical time’.