По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

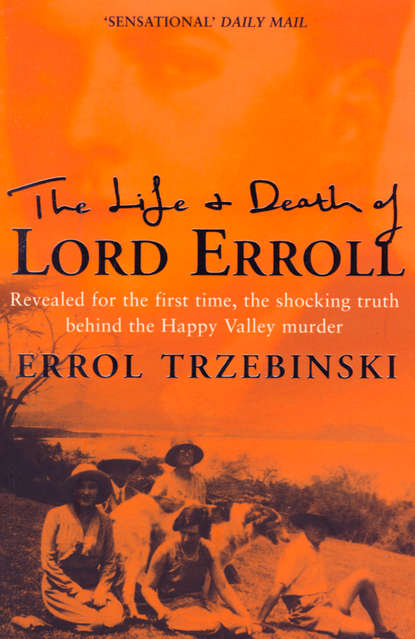

The Life and Death of Lord Erroll: The Truth Behind the Happy Valley Murder

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

(#litres_trial_promo) Imray could not bring himself to believe Swayne’s suggestion that ‘their guns had been spiked by a higher authority’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Inspector Fentum, the detective in charge of Karen police station, and Imray eventually became colleagues. By the time they met, Fentum had, according to Imray, ‘crawled to his position of Assistant Superintendent’. Like Swayne he had believed that an ‘inner cabal’ had been involved.

At one point Imray broached a subject that appeared to make him nervous. He warned: ‘this information is very near the knuckle’ and should ‘remain in the shadowlands just in case there [is] any reprisal’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Imray also told me about an ex-policeman who had known Diana for years, whom I might be able to persuade to meet me. But Imray cautioned me that he had encountered again and again a ‘certain disinclination’ in police colleagues in Nairobi to discuss this long-past event. At first Imray had put this reluctance down to the fact that the case had not brought credit to the force, but later, despite his own high position in the force, his own fear had prevented him from attempting to gain access to the police files or the court proceedings: ‘to do so would be inviting trouble. There would have been all sorts of complications.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Imray also informed me that after his departure from service in Kenya the possibility of recruitment to MI6 had cropped up. Following his interview, he had decided against the job, but confessed to me that at this point he too had come across the theory that Erroll had been ‘rubbed out’ by British Intelligence in Kenya.

The Erroll family have always been dissatisfied with the many salacious accounts of Lord Erroll’s life and death. Dinan, his only child, suffered greatly to see her father so misrepresented. There was even a rumour spread some time after his death that she was not Lord Erroll’s daughter – as if not satisfied with blackening his name, gossip-mongers wished to taint the lives of his progeny also. The physical likeness of her son Merlin, the 24th Earl, to his grandfather Lord Erroll put paid to that rumour.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The Erroll family had made attempts to find out the truth about their forebear. When I visited the Earl and Countess of Erroll in August 1995 I was handed a file to scrutinise. It contained correspondence from Merlin Erroll’s father, Sir Iain Moncreiffe, going back to 1953. His fruitless search through official archives on Erroll had led him to conclude that something ominous was lurking.

(#litres_trial_promo) Merlin Erroll had drawn similar blanks in 1983 when he had turned to the head of the Search Department in the War Office Records for information on his grandfather. In fact, there had even been an apology from the Ministry of Defence ‘for such a negative report’, and the hope had been expressed that further information ‘might be forthcoming’.

(#litres_trial_promo) It was not. It was general knowledge in the family that Erroll had received a posthumous Mention in Dispatches for ‘doing something on the Eritrean border’, but when Merlin entered into correspondence with a Major A. J. Parsons to find out more about it, he did not get far. Parsons pointed out, ‘The major campaign did not start until after he was dead’, and he could confirm only the Earl’s ‘suspicion that Mention in Dispatches can be awarded for both meritorious and gallant service’.

(#litres_trial_promo) He had enclosed photocopies of the supplement to the London Gazette which published ‘the award to your grandfather’, and, he pointed out, ‘you will note that the preamble clearly states that awards were made to members of the Staff’, but there was no more detailed indication of how Lord Erroll had earned the Mention. Parsons had requested that the Army Records Centre trace Erroll’s personal service file. Having studied the file carefully, Parsons sent Merlin a copy of Erroll’s Army Form B199A recording his ‘intimate knowledge of France, Belgium, Scandinavia, Kenya Colony and Germany (four years)’ and stating that his French was fluent and his German was ‘fair’.

(#litres_trial_promo) His covering letter said, ‘Unfortunately, it is sparse in content and gives very little detail of his military career, other than those shown … It is regrettable that the file does seem to have been “weeded” quite severely.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The weeding of sensitive information is well known to researchers. Material in files closed under the thirty- or fifty-year rule is sometimes burnt or shredded before the files are released.

(#litres_trial_promo) I had been advised by one of the former secret agents I interviewed to watch out for any evidence of arson, missing documents, and papers scattered among alien files, since these could have been acts of sabotage perpetrated by agents in time of war.

(#litres_trial_promo) One example of this was the Public Record Office file at Kew on Sir Henry Moore, Governor of Kenya at the time of Erroll’s murder. Marked ‘secret’, its contents had obviously been shuffled as there was no discernible order to the documents inside.

(#litres_trial_promo) The only month for which the file contained no information was January 1941, the month of the shooting.

Among Merlin Erroll’s papers there was a 1988 article in the Glasgow Herald by Murray Ritchie: ‘Hundred-year Shroud on Happy Valley Mystery’.

(#litres_trial_promo) While researching his article at the Public Record Office at Kew, Ritchie had come across a file listed under the general files for Kenya, marked with an asterisk denoting ‘Closed for a hundred years’. He was informed such closures were highly unusual – normally involving security, the royal family or personal records whose disclosure would cause distress to living persons. Ritchie had taken the number of this mysterious file. In his article he describes how the file had been brought towards him at the counter, but the bearer, pausing briefly to have a word with a colleague, had then carried it away.

Following the release in the 1990s of certain colonial files, I came to see the file that had eluded Murray Ritchie. While there were matters to do with Kenya in it, there was no mention of Lord Erroll. Instead there were some two dozen folios – each stamped ‘secret’, pertaining to Prince Paul and Princess Olga of Yugoslavia. They and their children had been kept under house arrest on Lake Naivasha in 1941.

(#litres_trial_promo)

I then discovered evidence of another file: it was listed in the Kenya Registers of Correspondence – under ‘Legislative Council. Death of Lord Erroll (103/3)’ – but marked ‘Destroyed Under Statute’. Fortuitously I stumbled across a document in yet another file that must have been transferred from this destroyed file – an instance of ‘papers scattered among alien files’ perhaps. It was a minute from Joss’s brother Gilbert, ‘[w]ho would be glad of any information in connection with the death of his brother’ – dated 27 January 1941.

(#litres_trial_promo)

By August 1996, I felt that my search for governmental documents on Lord Erroll was a wild-goose chase. The Metropolitan Police Archives had redirected me to the Public Record Office at Kew. They had warned me that there were no records about the policing of Kenya, suggesting I contact the Foreign and Colonial Office, which I did in July 1996 only to discover that my request had already been automatically referred there from the Met. The Foreign and Colonial Office simply referred me back to Kew again, to what transpired to be the Prince Paul file.

I began to realise that I had as much chance of finding any official papers on Erroll, as he had of leaping from his grave in Kiambu to tell me himself what had really happened to him. Even Robert Foran’s History of the Kenya Police

(#ulink_4a2d535b-0402-592d-94f4-f31feb907aa7) is silent on the subject of the Erroll murder.

(#litres_trial_promo) It contains not even the names, let alone any other details, of the team investigating it. References in Foran’s book to relevant issues of The Kenya Police Review led me to believe that I would be able to locate these at least. Yet not a single copy was in the possession of any library in England. I was able to trace only one issue, through a private source. And I could not find any copies of The British Lion, a fascist publication in which, I had been assured, Erroll’s name had appeared. When I applied at Colindale Newspaper Library, I was informed that all three volumes of it that they possessed appeared to have been stolen the year before.

In 1988, Merlin Erroll had invited anyone to come forward who could throw light on his grandfather’s military or political career, observing, ‘Some say that the affair with Diana was a red herring.’

(#litres_trial_promo) One response came from a retired Lieutenant-Colonel John Gouldbourn, who had been with the Kenya Regiment in 1940. Gouldbourn’s view was forthright: ‘I do not doubt that there was a “cover-up” of the murder by the judiciary, the police and the military in that order. There were sufficient persons with an interest for there to be an “inner cabal” … You will appreciate the East African Colonial Forces (the KAR)

(#ulink_646c86d8-468e-50a5-8289-fed07d54e13c) and the South African Division were poised to attack Somaliland. The dates would have been known to Joss Erroll. How discreet Erroll was is anybody’s guess.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

When I first met John Gouldbourn in October 1995 he had whipped out his army identification papers and handed them to me – ‘so that you know that I am who I say that I am’. In all my years meeting interviewees, this procedure was a first. But for Gouldbourn, accustomed to the etiquette of the Intelligence world, proving one’s identity had become a matter of common courtesy. He provided me with names, but no addresses, of people who he thought would be helpful to my research.

(#litres_trial_promo)

I managed to track down some of those who were still alive. I located Neil Tyfield in 1996. He had been in Military Intelligence at Force HQ in Nairobi and had had a ‘team of young ladies’ working for him there. Tyfield told me that a number of officers had been posted out of Nairobi after Erroll’s death so that they would not be able to testify at Broughton’s trial. But the most valuable contact name that Gouldbourn gave me was, ironically, that of someone who insists on anonymity but has allowed me to use his ‘official’ cover name, S. P. J. O’Mara, because ‘those few who may be interested in the identity behind it will recognise it’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Gouldbourn was insistent that O’Mara had had something to do with the ‘cover-up’ surrounding Lord Erroll’s death.

O’Mara had been an extremely young officer in the King’s African Rifles in 1940. Ian Henderson, the son of a Kenya settler family and he too an officer in the KAR during the war, was his commanding officer in Nanyuki in 1940. Roddy Rodwell had told me how this same man had tried unsuccessfully to recruit him for MI6 after the Second World War. O’Mara knew all about Ian Henderson’s career both during and after the war, including specific dates, corroborating what Roddy had told me. O’Mara threw light on many of the twists and turns that had set Erroll’s fate. When I told him that I had encountered fear among several interviewees he responded, ‘Fear of whom? [Fifty] years later? Only an SIS operation carries such a long shadow.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Stymied by the lack of access to official government papers on Lord Erroll’s career, I published a request for information in the Overseas Pensioner and Jambo, the English organ of the East African Women’s League, from anyone with anecdotes or photographs of Erroll. Through Jambo I received a letter in autumn 1996 from Anthea Venning, whose father had been a Provincial Commissioner in Kenya and had worked with Erroll on the Manpower Committee when war loomed. Anthea Venning was a rich source of information. In particular she led me to an old friend of hers called Tony Trafford, whose testimony is at the heart of the account of Lord Erroll’s death propounded in this book.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Tony’s father H. H. Trafford had been taken out of retirement on account of the war to undertake certain Intelligence duties. A former District Commissioner, he had confided to Tony that records existed in the Commonwealth Office, East Africa Section, indicating that it had been a woman that had shot Erroll. The theory that a woman pulled the trigger was well worn in Kenya. In the early 1980s H. H. Trafford had been approached by the maker of the film White Mischief and by someone at the BBC for any light he could shed on the murder. He told the latter bluntly that ‘though he had left the service there were certain matters he was not allowed to make comment on. Erroll being a case in point.’ He was similarly reticent with the White Mischief crew. Trafford had in fact been required to take the oath of the Official Secrets Act twice, once at the outset of his career and then again when he came out of retirement during the war.

(#litres_trial_promo) His Intelligence duties involved among other things a top-secret interrogation of Broughton in 1941 entirely separate from the police and the court proceedings.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Tony Trafford, Kenya-born, was seconded to British Intelligence in 1940.

(#ulink_29cadcff-42ed-542e-b494-17e293290318) He had worked all over Kenya and lived in Naivasha until 1963, leaving at Independence. He now lived on the Isle of Wight. Our initial exchanges revealed a character very sure and knowledgeable. Out-of-the-way places in Nairobi, road names most of which had been changed at Independence, the layout of the Maia Carberry Nursing Home were details that only someone who had worked there would know. His knowledge of Kenya’s topography, of the idiosyncrasies of its tribes and elderly settlers – contemporaries of his father with whom I was so familiar from my own research – convinced me that he had a brilliant memory and eye for detail. I checked the details of what he told me about the battalions moved into Kenya for the preparation of the Abyssinian campaign and found these were accurate. Tony was even able to provide me with the reason why during the war the RAF had been stationed at Wilson Airfield rather than Eastleigh, the newly built aerodrome. He also knew that Joss had been up for promotion shortly before his death. This is not general knowledge; I discovered the fact only through private correspondence between the 24th Earl of Erroll and the MOD.

Throughout my dealings with Tony Trafford, he was nervous about discussing Lord Erroll’s murder on the telephone. In order to protect his identity he chose his own cover name, Mzee Kobe (which means ‘Old Tortoise’ in Swahili). He wrote a twenty-five-thousand-word document for me detailing exactly how and by whom Erroll had been shot. This document, which I shall call the Sallyport papers, took him months of effort to compile and its contents reveal an extraordinary story of intrigue. Trafford died on 25 August 1998 shortly after completing his account. Interestingly, both the Sallyport papers and O’Mara’s correspondence uphold the same theory as to why Lord Erroll was killed.

The resounding implication of my research was that a new portrait of the 22nd Earl of Erroll needed to be made, not only to redress the calumnies, errors and exaggerations which have so tarnished his reputation in the past half-century, but to make clear that there were far more compelling motives for killing Erroll than sexual jealousy.

* (#ulink_5937dc41-3718-53b7-8736-a9b690333839)Vlei: in South Africa, a shallow piece of low-lying ground covered with water in the rainy season.

* (#ulink_1baf60ed-30a6-5e92-8f14-fe7444333be3)Broughton was to commit suicide in Liverpool.

* (#ulink_9fc5da5f-6c02-5df2-a90c-ac09a7766736)In 1903, W. Robert Foran had been in charge of Nairobi police station with the help of only three other European police officers (‘The Rise of Nairobi: from Campsite to City’, The Crown Colonist, March 1950, p. 163)