По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

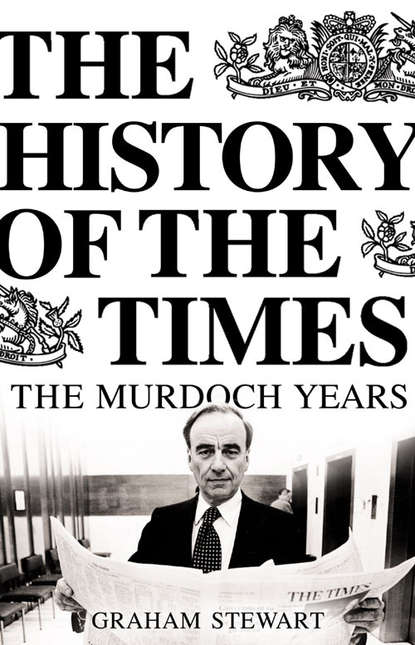

The History of the Times: The Murdoch Years

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

This is a sad day for Fleet Street, which is to see the greatest concentration of newspaper monopoly in its history. It is a sad day for the Conservative Party, which appeared this afternoon to have abandoned its traditional role of the opponent of large monopolies whenever possible.[82 - Hansard, 27 January 1981.]

Aitken was one of five Conservative MPs (the others were Peter Bottomley, Hugh Fraser, Barry Porter and Delwyn Williams) who defied a three-line whip and voted with the Opposition. It was in vain, and the Commons divided 281 to 239 against referring the sale. Murdoch had won a major battle. Securing the job cuts with the unions remained the only hurdle before Times Newspapers would be in his hands.

But while he had won the vote, not everyone was convinced his case had won the argument. Although he would soon accept Murdoch’s shilling, Harold Evans wrote Aitken a letter congratulating him on his speech.[83 - Jonathan Aitken to the author, interview, 27 May 2003.] There was a widespread belief that it had all been a stitch-up. Aitken had alleged that Thomson had suspiciously ignored several serious bids because it had already decided upon Murdoch. But were the names Aitken reeled off superior bidders? Rees-Mogg himself thought Murdoch a better option than his own consortium. Atlantic Richfield was about to move out of British newspaper ownership. Associated Newspapers could not guarantee The Times’s future. The idea that the editorial independence of the paper would be in safer hands with Lonhro’s Tiny Rowland was, as the Observer would later discover, highly contestable. If Brunton had pre-judged Murdoch’s suitability over these alternatives, might it not have been on the basis of an honest assessment of who offered the best future – perhaps the only future – for The Times? And if Lord Roll was a ‘banker of fees’ would he not have urged acceptance of the far higher bid from Rothermere’s Associated Newspapers?

The controversy was kept alive when, only a month after Biffen had made his statement in the Commons, the American oil company Atlantic Richfield sold the troubled Observer to Outrams, a subsidiary of Tiny Rowland’s Lonhro Group. Given that the Glasgow Herald was the closest Outrams/Lonhro could claim to owning a national newspaper, Biffen’s decision to refer the bid to the Monopolies Commission appeared perverse. Memorably dubbed by Edward Heath the ‘unacceptable face of capitalism’, Rowland had made himself objectionable to conservatives, socialists and liberals in equal measure and could find fewer defenders than Murdoch. The manner in which the Observer had been sold to him created unease, for the first that any of the editor-in-chief, the editor or the board of directors knew of it was after the deal had been done. There was also a more clearly defined question of public interest, in particular whether there was a conflict between the Observer’s extensive coverage of African affairs and Rowland’s business interests there. The Monopolies Commission could find no evidence to assume that it would and permitted the deal to go ahead subject to the installation of independent directors on a model similar to that adopted at Times Newspapers.[84 - The Times, 26 February 1981; Alan Watkins, A Short Walk Down Fleet Street, pp. 178–9; Jenkins, Market for Glory, pp. 169–70.] The experience was not to prove a happy one. But in February 1981 there remained many who could not see the consistency in the Government’s handling of newspaper takeovers.

Whatever the political symmetry between the Thatcher Government and Rupert Murdoch, the decision not to refer the TNL purchase was only legally possible on the grounds of the papers’ unprofitability. The Thomson submission to Biffen had claimed, ‘neither The Times nor the Sunday Times are economical as going concerns and as separate newspapers under current circumstances’.[85 - Thomson submission to the Department of Trade and Industry.] That The Times was in dire straits was not in doubt. But could that really be said of the Sunday Times, whose problems were hoped to be but temporary?

The TNL statistics sent out by Warburgs to prospective buyers had shown that the Sunday Times had actually scraped into the black in 1980 and by 1983 would be making projected profits of £13 million. John Smith immediately challenged Biffen on these figures since they appeared at odds with the statement he had given to the Commons. Biffen had to concede that he had based the paper’s loss on an estimate of the first nine months of 1980 and not, as MPs had been led to assume, the first eleven.[86 - John Biffen to John Smith, 3 February 1981, letter reprinted in The Times, 4 February 1981.] Harold Evans was not alone in resenting the way in which those seeking to avoid a referral had treated his paper. He found that many of his journalists ‘objected to being swept into what they saw as a large, alien publishing group on the sole grounds that it was necessary to save The Times’.[87 - Evans, Good Times, Bad Times, p. 143.] This now became a problem. The NUJ chapel of the Sunday Times decided to challenge Biffen’s non-referral in court. The action could cost £60,000 – a sum that was far beyond the chapel’s reach. Negotiations were opened with Rothermere’s Associated Newspapers to see if they would underwrite the expense. The intermediary was Jonathan Aitken. But Associated were hesitant and, with only thirty-six hours to go before the court hearing, the chapel called off the action following Murdoch’s promise that two working journalists would be appointed to the TNL Holdings board.[88 - Ibid., pp. 151–3; Sunday Times, 18 February 1981.]

Murdoch could now turn his attention to jumping the final hurdle: agreement with the unions. Historically, he had not been one of the unions’ principal bogeymen. In 1969, they had emphatically preferred his bid for the Sun to that of Robert Maxwell who promised under his ownership a paper that ‘shall give clear and loyal support at all times to the Labour movement’ but who wanted to cut the number employed printing the paper.[89 - Jenkins, Market for Glory, p. 58.] Compared to Rothermere who might close The Times, or the Rees-Mogg consortium that wanted to move printing to the provinces, Murdoch seemed the best bet for keeping jobs at Gray’s Inn Road. Because of this, Bill Keys (SOGAT), Joe Wade (NGA) and Owen O’Brien (NATSOPA) had written on the day after Thomson had accepted Murdoch’s provisional bid to Michael Foot, Labour’s Deputy Leader, urging him not to press for a referral to the Monopolies Commission.[90 - The Times, 13 February 1981.] The appeal fell upon deaf ears, but it was a positive sign of how they regarded Murdoch.

News International and the unions had until 12 February to agree a deal. A 30 per cent cut in the four thousand jobs at TNL was demanded. If enough voluntary redundancies could not be agreed, compulsory ones would make up the shortfall. There would also have to be a wage freeze until October 1982. Murdoch put two of his most doughty negotiators in charge of the talks. One was John Collier. Collier had been a NATSOPA official, working for the Guardian back in the days when it still retained Manchester in its title. He had joined Murdoch’s News Group Newspapers following its purchase of the Sun, becoming general manager in 1974. He knew how Fleet Street negotiations worked. In contrast, his accomplice had not even set foot in Britain before. But Murdoch had every confidence in the ex-secretary of the Sydney Ten-pin Bowling Association, Bill O’Neill. He had started as a fifteen-year-old apprentice in the composing room of the Sydney Daily Mirror. Like Collier, he had been active in the print union although disgust at the outlook of its pro-Communist officials led him to seek out union responsibilities that were less overtly political. He was still at the Sydney Mirror when its owners, Fairfax, sold it to Murdoch. The new proprietor promptly set about reinvigorating the run-down title in a manner similar to his later strategy at the Sun. By the mid-seventies, O’Neill had switched to the management side. When, in early 1981, Murdoch asked him what he thought of the intention to buy The Times, O’Neill mumbled something about barge poles. Murdoch shot back, ‘it’s obvious you’ve been talking to the wrong people’, and told him that he should expect to be in London for only as long as it took to finalize the deal with the unions there – which he estimated at two weeks. This was one of Murdoch’s less accurate predictions.[91 - O’Neill, Copy Out.]

In truth, the scope for trimming departments stretched far beyond what was discussed. When a thirty-year old Iowan named Bill Bryson arrived as a subeditor on The Times’s company news desk in the dying days of the Thomson ownership he was astonished by the work culture he encountered. His colleagues wandered in to the office at about 2.30 in the afternoon, proceeded to take a tea break until 5.30 p.m. after which they would ‘engage in a little light subbing for an hour or so’ before calling it a day. On top of this, they got six weeks’ holiday, three weeks’ paternity leave and a month’s sabbatical every four years. Bryson was equally taken aback by the inventive approach to filing expense claims and the casual attitude of the reporters in his section, many of whom stumbled back to the office after a lengthy liquid lunch to make ‘whispered phone calls to their brokers’. ‘What a wonderful world Fleet Street then was,’ Bryson concluded twelve years later when he wrote the episode up with only mild exaggerations for comic effect in his best-selling book on his adopted Britain, Notes from a Small Island, adding wistfully, ‘nothing that good can ever last’. Suddenly, Murdoch’s men – ‘mysterious tanned Australians in white short-sleeved shirts’ – began roaming around the building armed with clipboards and looking as if ‘they were measuring people for coffins’. Soon company news got subsumed into the business news department and Bryson found himself working nights and ‘something more closely approximating eight-hour days’.[92 - Bill Bryson, Notes from a Small Island, pp 46–7.]

Despite the extent of the options for where cuts could be made, Collier and O’Neill were faced with a massive task to reach agreement with all fifty-four separate chapels in the twenty-one days between Murdoch’s deal being agreed in principle with Thomson and the 12 February deadline. Invariably brinkmanship played its part but on the final day a compromise was reached. The TNL payroll was cut by 563 job losses, a reduction of around 20 per cent. This was achieved by voluntary redundancy at a cost of around £6 million to News International. It was telling that removing a fifth of the workforce did not appreciably lower the quality of the product. Importantly, agreement was reached to print the supplements (the Times Literary, Times Educational and Times Higher Education) outside London. This probably saved the life of the loss-making TLS. But the proposed wage freeze would only last for three months, there were no compulsory redundancies and no movement from the unions towards allowing journalists direct input. ‘Double-key stroking’ would remain. Harold Evans later concluded that the negotiations were ‘an opportunity forgone’: of the 130 jobs cut from the 800-strong NATSOPA clerical chapel, 110 were actually unfilled vacancies (in itself an extraordinary statistic at a time of soaring unemployment) and the most militant union fathers kept their jobs. But the truth of the matter was that there was little prospect of the newspapers being printed had News International tried to sack the unions’ spokesmen. At about this time, Len Murray, the general secretary of the TUC, confided to Murdoch his long-held belief that the Fleet Street proprietors had got the trade unions they deserved. With just a hint of menace, Murdoch replied, ‘well, now perhaps the unions have got the proprietor they deserve’. He appeared to mean it. Asked how he would respond to any new bout of industrial action at Gray’s Inn Road, Murdoch told the press, ‘I will close the place down’.[93 - O’Neill, Copy Out, p. 15; Sunday Times, 15 February 1981; Evans, Good Times, Bad Times, p. 182; Grigg, The Thomson Years, p. 576; The Times, 13 February 1981.] It was an unequivocal response from the man who was being interviewed because he had just officially become The Times’s owner.

V

Richard Searby believed Rupert Murdoch’s desire to own The Times was deep-seated and stretched back to the splendid engraved inkwell that the paper’s owner, Lord Northcliffe, had presented to his father.[94 - Richard Searby to the author, interview, 11 June 2002.] At Geelong Grammar, a boarding school labouring under the tag ‘the Eton of Australia’, the boys mocked the young Rupert with his father’s nickname, ‘Lord Southcliffe’. In fact it was his first name, Keith, that Rupert shared with his father.

The friendship between Northcliffe and Keith Murdoch had been forged during the First World War. In 1915 while employed by one of the news agencies, Keith Murdoch had been sent out to cover the Dardanelles campaign where Australian and New Zealand (Anzac) soldiers were suffering heavy casualties. He quickly surmised that the senior command was incompetent and that heroic Anzac troops were being let down by their British counterparts. In fact, he was not on the front line and much of his information came from a dissatisfied reporter from the London Daily Telegraph. But if his sources were weak his readership was focused. His report landed on the desk of the Australian Prime Minister and, on reaching London, Keith Murdoch went to The Times with his account. Northcliffe, the paper’s editorially interfering proprietor, read it and told the driven Australian journalist to pass it to the Prime Minister. Asquith promptly circulated it to his Cabinet.

The commanding officer, General Sir Ian Hamilton, blamed his subsequent removal on Murdoch’s coloured account. The Anzacs’ withdrawal from the campaign also came to be seen as stemming from what had been written. Keith Murdoch’s version would eventually be summarized by his admiring son: ‘it may not have been fair, but it changed history’.[95 - Quoted in William Shawcross, Murdoch, p. 38.] In the year the son bought The Times, he co-financed a film, Gallipoli, starring Mel Gibson, in which effete British commanders casually sacrificed the lives of courageous anti-Establishment Australians. Given a choice between truth and legend, the son continued to promote the legend.

From the moment of Keith Murdoch’s Dardanelles scoop, he had the attention and support of Lord Northcliffe. The owner of The Times became a mentor for the motivated Australian, inspiring him and including him in his influential social circle. And Murdoch learned a good deal from the man who had done so much to create the mass-appeal ‘new journalism’, launching new titles and rejuvenating old ones like The Times. When Murdoch struck out on his own, taking up the editorship of Australia’s Melbourne Herald, Northcliffe even went over there to sing his praises. The Herald’s directors soon had cause to join in: circulation rose dramatically and its editor joined its management board, buying other papers and a new medium of enormous potential – a radio station. Growth would be fuelled by acquisition, creating a business empire in a country in which the print media was entirely localized. It was also a route to making enemies who believed Keith (from 1933, Sir Keith) Murdoch’s expansionist strategy not only gave the Herald and Weekly Times Group too much financial clout but also made its managing director a kingmaker in Australian politics as well. The Herald Group’s competitors were especially dismayed when with the outbreak of the Second World War he was appointed Australia’s director-general of information. The role of state censor was certainly not in keeping with the role he had played in the previous conflict. But when, in 1941, ten-year-old Keith Rupert Murdoch arrived at boarding school, it was to discover to his surprise that it was his father’s crusade to bolster the power of the press that was often looked at with mistrust and apprehension.

Though he showed little interest in Geelong’s emphasis on team sports, Rupert Murdoch’s childhood had been predominately spent outdoors with his three sisters riding and snaring (Rupert persuaded his sisters to skin the unfortunate rodents for a modest fee while he sold on the pelts at a larger mark-up). Home was his parents’ ninety-acre estate, Cruden Farm, thirty miles south of Melbourne. The house itself was extended over the years and by the time Rupert was growing up there it resembled the sort of colonnaded colonial residence more generally associated with Virginian old money. But rather than be overexposed to its creature comforts, Rupert spent his evenings between the ages of eight and sixteen in a hut in the grounds. His mother thought it would be good for him.[96 - Shawcross, Murdoch, pp. 47–9; Rupert Murdoch to the author, interview, 4 August 2003.]

Cruden was named after the small Aberdeenshire fishing village from which Rupert Murdoch’s grandfather, the Revd Patrick Murdoch, had lived and preached. A Minister in the principled and unyielding Calvinism of the Free Church of Scotland, the Revd Murdoch had in 1884 transferred his mission to the fast-expanding metropolis of Melbourne. Widely admired, by 1905 he had risen to the church’s highest position in the country – moderator of the General Assembly of Australia. The grandfather on his mother’s side provided young Rupert with a contrasting influence: Rupert Greene was an affable half-Irish, free-spirited gambling man. Not surprisingly, commentators came to see Rupert Murdoch as, in some ways, a composite of the two.

In 1950 Murdoch went up to Oxford University. For the most part he enjoyed student life there and later became a generous benefactor of his college, Worcester. But at the time, and despite the efforts of such eminent tutors as Asa Briggs, it was not his Philosophy, Politics and Economics degree course that held his attention. At the Geelong school debating society, he had espoused radical and frequently socialist views. He maintained this stance at Oxford, often attending Union debates where bestrode confidently the young Tory matador, Rees-Mogg of Balliol. Murdoch, however, chose to stand for office in the university Labour Club. The club’s president, the young Gerald Kaufman, had other ideas, and had him disqualified for illegally soliciting votes (canvassing being – technically – forbidden). Some thought it was Murdoch who was indulging in gesture politics. He kept a bust of Lenin in his rooms, but they were among the finest in college. He was also one of the few students committed to the triumph of the proletariat to own, in his final year, a car in early 1950s Oxford. He had an eclectic circle of friends in a whimsical philosophical society he joined named after Voltaire. Cherwell described him as ‘turbulent, travelled and twenty-one, he is known … as a brilliant betting man with that individual Billingsgate touch. He manages Cherwell publicity in his spare time.’[97 - Quoted in Shawcross, Murdoch, p. 61.] Relegated to even sparer time were his studies and in 1953 he went down with a third-class degree.

On coming down, he got his first taste of Fleet Street as a junior sub at the Daily Express. The pride of Beaverbrook’s titles, the Express was at that time close to the summit of its prestige and popularity. Edward Pickering found time to keep a paternal eye on Sir Keith’s son as he toiled away on the subs desk. Indeed, Pickering assumed the mentor’s role for Rupert Murdoch that Northcliffe had played for his father. And the young journalist appreciated the training, retaining throughout his career the highest regard for the man he would ultimately make executive vice-chairman of Times Newspapers.

In September 1953, Murdoch returned to Australia. But it was not the homecoming of which he had once dreamed. Sir Keith had died the previous year while his son was still up at Oxford. It was a terrible blow. ‘My father was always a model for me,’ Murdoch later said. ‘He died when I was twenty-one, but I had idolized him.’[98 - Murdoch quoted in Chief Executive magazine; quoted in TNL News, November 1982.] And the son had learned something else from his father’s experience: Sir Keith had built up a newspaper empire, but as a manager, not an owner. After death duties had taken a sizeable claim, the money left for his widow Lady (later Dame) Elisabeth, son and three daughters was held in the family holding company, Cruden Investments. The Herald Group persuaded Lady Elisabeth to sell them the Murdoch half-share in the Brisbane Courier-Mail on terms that proved highly favourable to the Herald Group. Thus the only proprietorship left for Rupert Murdoch to inherit was a controlling interest in News Limited, owner of a single by no means secure daily, the Adelaide News – which was not even the biggest paper in Adelaide – and its sister title, the Sunday Mail. The immediate response of the Herald Group was to try and strip him of it. On failing to persuade Lady Elisabeth to sell them the Murdoch stake in News Limited, they announced their intention to drive the Adelaide News out of business. Sir Keith had helped make the Herald Group the most important media company in Australia. Its treatment of his family on the morrow of his death caused tremendous acrimony. And it instilled in the son an important lesson about where power lay. He would follow in his father’s footsteps, but with one crucial difference – he was determined to own the papers he built up.

The first objective was to see off the Herald Group’s assault on the Adelaide News and Sunday Mail. The attack was repulsed and News Limited became the basis of Rupert Murdoch’s acquisitions fund. Within two years of taking the helm he saw its net assets double. After purchasing a Melbourne women’s magazine, the loss-making Perth Sunday Times became his first newspaper acquisition in 1956, when he was still only twenty-four. He transformed its sales but kept its sensationalist reporting. The purchase of other small local papers followed. Then he bid successfully for one of the two licences for Adelaide’s first television channels. His Channel 9 beat the rival Channel 7 to be first on the air and started generating enough revenue to finance far grander dreams of expansion. Sydney’s newspaper market was a virtual duopoly of the Fairfax and Packer families but in 1960 Murdoch got a foot in the door when Fairfax sold him the Mirror, a downmarket paper which had become something of an embarrassment to the company and which when sold, it was imagined, would be less of a threat if owned by an outsider like Murdoch than by a more direct rival. Instead, the result was a no-holes-barred circulation war in which Sydney’s tradition of sensationalist reporting was surpassed.

In 1964 Murdoch launched his first new title. Based in the capital, Canberra, The Australian became the country’s only truly national newspaper. It was also a serious-minded broadsheet, committed to political analysis and in-depth reporting. In other words, it was a departure from its owner’s previous projects. Maxwell Newton, The Australian’s editor, recalled that on its first night Murdoch told him, ‘“Well, I’ve got where I am by some pretty tough and pretty larrikin methods … but I’ve got there. And now,” he said, “what I want to do – I want to be able to produce a newspaper that my father would have been proud of.”’[99 - Maxwell Newton in ‘Six Australians: Profiles of Power’, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 1 January 1966, quoted in Neil Chenoweth, Virtual Murdoch, p. 32.] He stuck with the paper ever after, despite its inability to return a profit.

In 1969, Murdoch made the great leap, breaking into the British market with a newspaper far removed from his product in Canberra. He had originally wanted to take control of the Daily Mirror, but purchasing sufficient shares proved impossible. The News of the World was a popular Sunday institution, long known as the ‘News of the Screws’ because of its stories about defrocked vicars and low goings-on in high places (or just low places if it was a slow news day). With six million copies sold each Sunday (down from a peak of over eight million in 1950), the raucous and right-wing publication had the largest circulation of any newspaper in Britain. But by 1968 its Carr family proprietors, giving the outward impression of ennui, found themselves fragmented and receiving the unwelcome attention of Robert Maxwell. In order to prevent Maxwell buying a third of their company’s shares, the Carrs opted to sell a 40 per cent stake to Murdoch. This seemed the best policy since, although the thirty-eight-year-old Australian would become managing director, he had promised that he would not seek to increase further his share and that Sir William Carr – or, in time, another member of his family – would continue to be chairman of the company. Within six months of the deal going through, Murdoch duly increased his share, entrenched his control of the paper and forced Sir William, incapacitated by illness, to resign. Murdoch then put himself forward as chairman. He regarded this as a matter of business sense. Others called it sharp practice.

It was the trade unions that provided Murdoch with his greatest coup. Maxwell, having been thwarted in his attempt to acquire the News of the World, hoped to buy the ailing Sun from the Daily Mirror’s owners, IPC. He would maintain the Sun’s left-leaning politics and would not let it challenge the Mirror directly for dominance. Delighted, IPC agreed generous terms of sale. But Maxwell also made it clear that in taking on a loss-making paper he would have to cut jobs and costs. The unions objected to this, and Hugh Cudlipp, IPC’s chairman, feared it might trigger a wave of union militancy that would disrupt production of the company’s highly profitable Mirror. Cudlipp had fathered the Sun in 1964 as a middle-market broadsheet (it replaced the defunct trade union-backed Daily Herald bought by IPC three years earlier) and did not want to contemplate infanticide. So he sold it for the trivial sum of £500,000 (of which only £50,000 was a down payment) to Murdoch, a man who – compared to Maxwell or the alternative of certain death – had the unions’ blessing. Over the next three years, the circulation of Murdoch’s Sun rose from under one million to over three million. The paper’s mix of sauce and sensationalism earned its new owner the sobriquet ‘Dirty Digger’. But more to the point, he now had his cash cow and could plan for expansion accordingly.

Yet Murdoch’s next forays into Fleet Street were unsuccessful. It seemed The Times would never come up for sale – Roy Thomson had pledged as much and was not in apparent need of ready cash. But the future of another illustrious title, the Observer, edited by Gavin Astor’s cousin David, appeared far less certain. In 1976, however, it preferred to sell itself for a mere £1 million to Atlantic Richfield rather than to the downmarket tabloid owner of the Sun and the News of the World. Like Thomson with Times Newspapers, Atlantic Richfield was a company making large profits from oil exploration that talked the language of moral obligation rather than business opportunity (at least until 1981 when it sold the loss-making paper to Tiny Rowland). In 1977, Murdoch’s was one of the raised hands in the crowded bidding for the fallen Beaverbrook empire. The prospect of breathing new life into the once mighty Daily Express, where nearly a quarter of a century earlier he had learned the subeditors’ craft from Edward Pickering, was naturally appealing. But he lost to a higher bid from Trafalgar House who placed a building contractor, Victor Matthews, behind the chairman’s desk of the newly named Express Newspapers.

But by this stage, Murdoch’s News Limited had spread to three continents. His first American acquisitions came in Texas when in 1973 he bought the San Antonio Express and its News sister paper. After a slow start the titles became increasingly profitable. An attempt to launch a rival to the National Enquirer proved unsuccessful but he was not to be put off by temporary reverses (he merely transformed his product into Star, a women’s magazine that by the early eighties returned a $12 million annual profit). The great test of his mettle came in 1976 when Dorothy Schiff sold him the liberal leaning New York Post. He paid $10 million for a paper that was haemorrhaging money, but rather than taking time to regroup he immediately pressed ahead, spending a further $10 million to buy New York magazine and Village Voice.

In the twenty-eight years between his father’s death and his acquisition of The Times, Murdoch had progressed from owning one newspaper in Adelaide to becoming a major presence across the English-speaking world with annual sales of over A$ 1 billion (£485 million). His News Corporation was valued on the Sydney stock exchange at £100 million. It owned half the shares in its British subsidiary, News International (owner of Times Newspapers and the tabloids of News Group Newspapers). The other half of News International’s shares was quoted on the London stock exchange with a value of £35 million. Yet the perceived imperative of keeping personal control had not been squandered in the midst of this expansion. The Murdoch family’s holding company, Cruden Investments, still owned 43 per cent of the parent company.[100 - Sunday Times, 15 February 1981; Daily Telegraph, 30 September 1981.]

Murdoch was able to pursue a policy of aggressive expansion because of the profitability of his London tabloids and by pointing to a proven track record in turning around under-performing titles. It was enough to secure credit from the banks. But his growing band of critics had come to credit him only with debasing the profession of journalism. Aside from his patronage of The Australian (and even here there had been evidence of his interference in editorial policy), he was now held in contempt by those who believed he had built success upon a heap of trash. His titles sensationalized events, trivialized serious issues (when indeed they bothered to report serious issues at all) and frequently allowed their zeal in getting a scoop to overcome questions of taste, fairness and honesty. More than any other, it was Murdoch’s name that had become associated with ‘tabloid journalism’ as a pejorative term.

From November 1970, the Sun sported topless women on its page three. Feminists and arbiters of decency loudly condemned this popular move. In fact, it was not exactly a Fleet Street first: as long ago as 1937 the high-minded Hugh Cudlipp, then editor of the Mirror’s Sunday sister paper, had reproduced a topless damsel chaperoned by the obtuse picture caption ‘a charming springtime study of an apple-tree in full blossom’. Even newspapers owned by such respectable figures as Lord Thomson and edited by William Rees-Mogg were not immune. Five months after the Sun launched its topless page three girls, The Times pictured one of them nude in a full-page advertisement for Fisons’ slimming biscuits (one reader asked whether the paper’s self-regarding 1950s advertising slogan ‘Top People Take The Times’ should be replaced with ‘Topless People Take The Times’; another wrote, ‘I hope this delightful picture has the same effect on The Times’s circulation as it does on mine.’). Although it proved a sell-out issue, it did not, however, start a broadsheet trend. In contrast, page three nudity became synonymous with the Sun. Those who did not believe masscirculation newspapers were the place for entertainment or triviality hated Murdoch’s winning formula every bit as much as a previous generation had chastised Northcliffe for giving the people what they wanted in place of what was thought good for them. In the case of the Sun and the New York Post, Murdoch had indeed taken serious-minded newspapers downmarket. But many of his offending newspapers (in particular the News of the World, the Perth Sunday Times and the Sydney Daily Mirror) had been peddling titillation, half-truth and questionable journalistic standards long before his arrival on the scene. But the increasing size not only of headlines – now often involving a comic pun – but also graphic photographs certainly made their wares more pervasive and intrusive.

Murdoch was not interested in the critics of his tabloids. In his eyes they were cultural snobs, seeking to enforce their own tastes on millions of people whose lives were lived in conditions about which the arbiters of taste demonstrated scant concern or understanding. Papers like the Sun and the New York Post were responding to a need, reflecting what their readers wanted to unwind with in the course of what was otherwise a day of toil. But Murdoch went further in the defence of his titles. They were not just a form of cheap entertainment; they were genuine upholders of a fearless fourth estate. What the cultural establishment branded scandal-mongering was, more often, an attempt to hold to account those in public life for their actions – public and private. While the self-righteous broadsheets lazily reported ‘official’ news after it had happened, the popular press regularly created the news in the first place, by uncovering what was actually going on behind the veneer of authorized pronouncement. It was, Murdoch asserted:

not the serious press in America but the muck-rakers, led by Lincoln Steffens and his New York World, who became the permanent opposition and challenged the American trinity of power: big business, big labour and big government. It was not the serious press which first campaigned for the Negro in America. It was the small, obscure newspapers of the Deep South.[101 - Rupert Murdoch, speech at Melbourne University, 15 November 1972.]

Nor was this a phenomenon of the New World. Having sympathized with the Confederates in the Civil War, zealously advocated the appeasement of Hitler in the 1930s and adopted an understanding attitude towards Stalin in the 1940s, The Times had, in its high-minded way, not always walked with angels.

Yet, it was the social and political comment in Murdoch’s tabloids that many of his critics found the most pernicious aspect of his influence. The proprietor had long since mislaid his bust of Lenin, but not his dislike of the class system, and in the first three general elections of his ownership, the Sun endorsed the Labour Party. But when it came out in support of Margaret Thatcher’s Conservatives for the 1979 election, left and liberal commentators perceived they were now up against a formidable foe that was hooking millions of innocent readers to right-wing policies by pandering to their fears and sugaring the poison with smut and light entertainment. It was as if the Sun had become the opiate of the people. Two headlines in the paper in the months leading up to the 1979 election became legendary: ‘Crisis? What crisis?’ misquoted what the Labour Prime Minister, James Callaghan, had said on returning from a summit in Guadeloupe (although it caught accurately the mood he conveyed) while ‘Winter of Discontent’ soon became the recognized description of the period of industrial strife.[102 - Sun, headlines, 11 January and 30 April 1979.] In fact the Richard III reference had actually been made by Callaghan in a television interview two months earlier, but it was the Sun’s usage that gave it wider currency. Despite the evidence – as Callaghan acknowledged – that there was a cultural sea change underway among the electorate in favour of Mrs Thatcher, discontented figures on the left began to believe that their arguments had been defeated not in a reasoned debate but by the cheap headlines of Murdoch’s newspapers and their equivalents on the advertising hoardings hired by Saatchi & Saatchi. Given that Murdoch was known to interfere in the line his newspapers took, it was reasonable to assume the right-wing slant was all his doing. In fact, the extent of the Sun’s partisan support for Mrs Thatcher was far more a case of its editor, Larry Lamb, dictating the paper’s politics to the proprietor. Murdoch’s instincts had been far more cautious. But editors were easily dispensable and it was Murdoch who gained the opprobrium, one that got worse the more he came to believe Lamb had made the correct call.

This was the background to Harold Evans’s determination to have legally watertight safeguards against Murdoch’s exercising any editorial interference in The Times and Sunday Times. And there were plenty of journalists on the payroll determined to assert their independent judgment from the first. The profile of Rupert Murdoch that appeared in The Times upon his gaining control of the paper was certainly not effusive. Dan van der Vat described a ‘ruthless entrepreneur … and pioneer of female nudity’ pursuing a strategy of taking his papers ‘down-market to raise circulation’. Murdoch was the owner in the United States of ‘the downmarket Star’ who ‘transformed in the familiar down-market manner’ the New York Post. Scraping the barrel to try and find something positive to say, van der Vat’s profile concluded that The Times and Sunday Times ‘each have the most demanding readership in Britain, and it is a well-known tenet of Mr Murdoch’s philosophy to give the readers what they want’. The leader article, written by Rees-Mogg and entitled ‘The Fifth Proprietorship’, was less keen to find fault. Sketching the previous four owners of the paper, it noted, ‘neither Northcliffe nor Roy Thomson … managed to solve its commercial problems. If Mr Murdoch does resolve those problems he will have achieved something which has defied the masters of his craft.’ In Rees-Mogg’s opinion, the new owner stood ‘somewhere between’ Northcliffe’s ‘editorial genius’ and Thomson’s outlook as ‘a business man’. Murdoch was ‘a newspaper romantic’.[103 - Leading article, ‘The Fifth Proprietorship’, The Times, 13 February 1981.]

Less happy with this affair of the heart was the new owner’s wife, Anna. Looking forward to bringing up a young family in New York, she did not want to be uprooted and moved to London, a city in which she had previously had bad experiences (in particular the murder of a friend by kidnappers who mistook the woman for their actual ransom target – Anna herself). The Times, she conceded, was ‘not something that I really want, but if Rupert wants it and it makes him happy I’m sure we’ll sort it out’.[104 - Quoted in Leapman, Barefaced Cheek, p. 174.] Nonetheless, for her husband’s fiftieth birthday on 11 March 1981, she presented him with a cake iced with a mock front page of The Times – into which he excitedly plunged the knife.

CHAPTER TWO

‘THE GREATEST EDITOR IN THE WORLD’

The Rise and Fall of Harold Evans

I

After fourteen years in the chair, William Rees-Mogg had made it clear he would relinquish the editorship once the transferral of The Times’s ownership was complete. Thus, the first question facing Rupert Murdoch was whether the new editor should be appointed from inside or outside the paper. It was recognized that existing staff would be happier with ‘one of their own’ taking the helm rather than an outsider who might sport alienating ideas about improving the product. But it was not the journalists who were footing the losses for a paper that, on current performance, was failing commercially. In making his recommendation to The Times’s board of independent national directors, the proprietor had to consider the signal he would be sending out both to the journalists and to the market outside about what sort of paper he wanted by how far he looked beyond the environs of Gray’s Inn Road.

There were three credible internal candidates. As early as 12 February, Hugh Stephenson, the long-serving editor of The Times business news section, had written to Murdoch asking to be considered for the top job.[105 - Hugh Stephenson to Denis Hamilton, 13 February 1981, Hamilton Papers 9383/12.] A left-leaning Wykehamist who had been president of the Oxford Union prior to six years in the Foreign Office, Stephenson had been with The Times since 1968. This was an impressive résumé, but not one especially appealing to the new proprietor who was, in any case, not an admirer of the paper’s business content. Even quicker off the blocks was Louis Heren, who had made his intentions known to Sir Denis Hamilton the previous day. He was probably the candidate who wanted the editorship most and his success would certainly have been something of a Fleet Street fairy tale. The son of a Times print worker who had died when his boy was only four, Louis Heren had been born in 1919 and grown up in the poverty of the East End before getting a job as a Times messenger boy. His lucky break had come when an assistant editor noticed him in a corner, quietly reading Conrad’s Nostromo. Subsequently, he was taken on as a reporter and, after war service, he developed into one of the paper’s leading foreign correspondents, sending back dispatches from Middle Eastern battlefronts where the new state of Israel was struggling for its survival, and from the Korean War and later becoming chief Washington correspondent. If not a tale of rags to riches, it was certainly rags to respectability and, as Rees-Mogg’s deputy, he was entitled to expect to be considered seriously. But the fact that he had been, to all intents and purposes, educated by The Times posed questions as to whether he was best able to see the paper’s problems from an outside perspective. He was also sixty-two years old. When he sent the new owner a list of suggested improvements to the paper, Murdoch replied, without much sensitivity, that he wanted an editor ‘who will last at least ten years’ and that another rival for the post, Charles Douglas-Home, ‘is more popular than you’.[106 - Quoted in Michael Leapman, Barefaced Cheek, p. 203.]

On this last point, Murdoch was well informed. Charles Cospatrick Douglas-Home (‘Charlie’ to his friends) was the popular choice, certainly among the senior staff. He was the man Rees-Mogg wanted as his successor and when the outgoing editor asked six of the assistant editors whom they wanted, five of them had opted for Douglas-Home. The chief leader writer, Owen Hickey, had even taken it upon himself to write to Denis Hamilton assuring him that Douglas-Home was the man to pick.[107 - Owen Hickey to Denis Hamilton, 11 February 1981, Hamilton Papers 9383/12.] At forty-four, he was the right age and since joining The Times from the Daily Express in 1965 he had held many of the important positions within the paper: defence correspondent, features editor, home editor and foreign editor. He had been educated at Eton and served in the Royal Scots Greys. He was the nephew of the former Conservative Prime Minister, Alec Douglas-Home, and his cousin, a childminder at the All England Kindergarten, had recently become engaged to the heir to the throne. So he certainly had highly placed ‘connections’ (a disadvantage in the eyes of those who believed having friends in high places compromised fearless journalism). But ‘Charlie’ was no society cyphen. He took his profession seriously and had well-formed ‘hawkish’ views, especially on defence and foreign policy – all likely to endear him to the new, increasingly right-wing proprietor. He was also something of a contradictory figure: a former army officer who no longer drank, a fearless foxhunter who did not eat meat and a gentleman who, like an ambitious new boy in the Whips’ Office, had once been caught keeping a secret dossier on the private foibles of his colleagues.[108 - John Grigg, The History of The Times, vol. VI: The Thomson Years, p. 376; Leapman, Barefaced Cheek, p. 201.]

Murdoch interviewed the three ‘internal’ candidates on 16 February although, since he already had a preferred candidate in mind, he was essentially going through the motions. The man he wanted was not an old hand of The Times. Having made such a success steering the Sun, Larry Lamb anticipated the call up and was deeply hurt when it did not come. ‘I would never have dreamt of it,’ Murdoch later made clear, ‘he would have been a disaster.’[109 - Rupert Murdoch to the author, interview, 4 August 2003.] Yet Murdoch’s critics, incredulous that he meant what he said about guaranteeing editorial independence, were still waiting to see which other stooge he would appoint. In an article entitled ‘Into the arms of Count Dracula’, the editor of the New Statesman, Bruce Page, informed his readers, ‘it is believed in the highest reaches of Times Newspapers that the candidate which [sic] he has in mind is Mr Bruce Rothwell. Rothwell can reasonably be described as a trusted Murdoch aide …’[110 - Bruce Page, ‘Into the arms of Count Dracula’, New Statesman, 30 January 1981.] But, whatever was now the practice at the New Statesman, The Times was not ready to be run by a man named Bruce. Murdoch had fixed upon someone very different – a hero in liberal media circles.

Even before the deal to buy Times Newspapers was done, Murdoch had invited Harold Evans round to his flat in Eaton Place and asked him whether he would like to edit The Times. It was a probing, perhaps mischievous, question since Evans was at the time still trying to prevent the Murdoch bid for TNL so that his own Sunday Times consortium could succeed. But Murdoch could have been forgiven for regarding the avoidance of saying ‘no’ as a conditional ‘yes’.

Harold Evans was the most celebrated editor in Fleet Street. At a time when standards were said to be falling all over the ‘Street of Shame’, Evans appeared to exemplify all that was best about the public utility of journalism. By 1981, he had been editor of the Sunday Times for fourteen years – thereby shadowing exactly the service record of his opposite number, Rees-Mogg, in the adjoining building at Gray’s Inn Road. The two editors were the same age but their backgrounds could not have been more different. Two years older than Murdoch, Harold Evans was born in 1928, the son of an engine driver. His grandfather was illiterate. Leaving the local school in Manchester at the age of sixteen, he had got his first job towards the end of the Second World War as a £1-a-week reporter on a newspaper in Ashton-under-Lyme. The interruption of national service with the RAF in 1946 led to opportunity: the chance to study at Durham University (where he met his Liverpudlian first wife, Enid) and later Commonwealth Fund Journalism fellowships at the universities of Chicago and Stanford. By 1961 he had become editor of the Northern Echo. Driven by its new editor, the Echo started to take its investigative journalism beyond its Darlington readership. Its campaign to prove the innocence of a Londoner wrongly convicted of murder gained it national prominence. One of those who took notice was the editor of the Sunday Times, Sir Denis Hamilton, who brought Evans down to London to work alongside him. The following year, 1967, he succeeded Hamilton as editor of the paper. It was a meteoric rise from provincial semi-obscurity. Evans immediately proved himself at Gray’s Inn Road. In his new role as editor-in-chief, Sir Denis’s patronage and guidance were useful and some of the paper’s success was the consequence of his own formula: the paper’s colour magazine (a honey pot for advertising) and major book serializations. But Evans built on these strong foundations and, assisted by Bruce Page, Don Berry and others, he entrenched the position of the Sunday Times as Britain’s principal campaigning and investigative newspaper.

In 1972, Evans drove the campaign with which his name, and that of the Sunday Times, will always be associated: the battle to force Distillers Ltd to compensate adequately the victims of its drug, Thalidomide. The immediate reaction – as he well anticipated – was Distillers’ withdrawal of £600,000 worth of advertising in the paper. The other equally swift response was an injunction silencing the Sunday Times’s attempts to reveal the history of the drug’s development and marketing. With great tenacity (and an understanding proprietor in Roy Thomson), Evans continued the fight through the courts and to Strasbourg. Distillers was eventually forced into a £27 million payout to its product’s victims. And at last, in 1977, the Sunday Times got to print the details of its story (although the print unions decided to call a stoppage that day, ensuring few got to read about it).

Under Evans, the Sunday Times was a paper with a liberal conscience. The paper appeared at ease with the more permissive and meritocratic legacy of the 1960s. The cynic within Murdoch may well have thought that he could silence the howls of protest about his being allowed to buy The Times by putting such a respected, independent and liberal-minded editor in charge of it. Indeed, to appoint the man who had spent the previous months trying to wreck the News International bid with his own consortium (and who had privately applauded Aitken’s attack on it in the Commons) appeared to show a spirit of open-minded forgiveness that few had previously associated with Murdoch’s public conduct. Surely the new owner could not be all that right wing or controlling if he put in charge a man who had wanted the Sunday Times to be part owned by that tribune of democratic socialism, the Guardian? This would certainly be a calming message to convey.

But there was genuine admiration as well. Back in 1972, Murdoch had played his part in the Thalidomide controversy. He had been behind the anonymous posters that suddenly appeared across the country ridiculing Distillers, hoping (unsuccessfuly) that by this means his papers could discuss the company’s role at a time when its legal proceedings made doing so contempt of court. Unusually for Fleet Street proprietors, Murdoch understood every aspect of the newspaper business – not just the accounts. Thanks to the efforts of his father and Edward Pickering at the Express, Murdoch could sub articles with effortless aplomb. In this respect, he had something in common with Evans – comprehensive mastery of the journalistic craft. For Evans was the author of such tomes as The Active Newsroom and Editing and Design (in five volumes) which covered almost every aspect of putting together the written (and pictorial) page. The two men also appeared to have a common outlook. They admired American spirit and drive (both later became American citizens) and neither wished to be considered for membership of the traditional British Establishment. Despite his migration to London, Evans still wanted to be considered something of an outsider and this attracted Murdoch. The American academic Martin Wiener had just written his influential book, English Culture and the Decline of the Industrial Spirit 1850–1980. Its message appealed to Murdoch who told a luncheon at the Savoy: ‘It is the very simple fact that politicians, bureaucrats, the gentlemanly professionals at the top of the civil service, churchmen, professional men, publicists, Oxbridge and the whole establishment just don’t like commerce.’ Apart from the reference to ‘publicists’, he had basically reeled off a list of the core Times readership. But he was not finished with his castigation: ‘They have produced a defensive and conservative outlook in business which has coalesced with a defensive and conservative trades union structure imposing on Britain a check in industrial growth, a pattern of industrial behaviour suspicious of change – energetic only in keeping things as they are.’[111 - Rupert Murdoch to the annual lunch of the Advertising Association, quoted in TNL News, April 1981.]

With this attitude, it is easy to see why Murdoch hoped for great things from a restless and meritocratic figure like Harold Evans. That he could be given a pulpit in the housemagazine of the Establishment while being sufficiently intelligent to prevent accusations of being a downmarket influence made him, in Murdoch’s view, the ideal candidate.

It was up to the independent national directors, sitting on the holdings board of Times Newspapers, to make the final decision. The board consisted of four peers of the realm, Lords Roll, Dacre, Greene and Robens who, before ennoblement, had been Eric Roll, civil servant and banker; Hugh Trevor-Roper, historian; Sid Greene of the National Union of Railwaymen; and Alf Robens of the National Coal Board. Two new directors nominated by Murdoch now joined them: Sir Denis Hamilton and Sir Edward Pickering. Hamilton’s appointment was uncontroversial but Dacre objected to Murdoch assuming Pickering would be acceptable without the directors first voting on it. There was an embarrassing delay at the start of the meeting while this was done although it was not entirely to the directors’ credit that they appeared to know little about one of Fleet Street’s most successful editors and longest serving figures.[112 - Richard Searby to the author, interview, 11 June 2002; Leapman, Barefaced Cheek, pp. 204–5.] It had been under Pickering’s editorship that the Daily Express had achieved its highest ever circulation. Suitably acquainted with his qualifications, the directors hastily assented to Pickering joining them and proceeded on to the main business – the appointment of the new editor. Under the articles of association, the proprietor had the power of putting forward his preference for editor. The directors had the right of veto but not necessarily the option of discussing who they actually wanted. Had they the right of proposition, the editorship would most likely have gone to Charles Douglas-Home. But it was Harold Evans’s name that Murdoch put before them.