По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

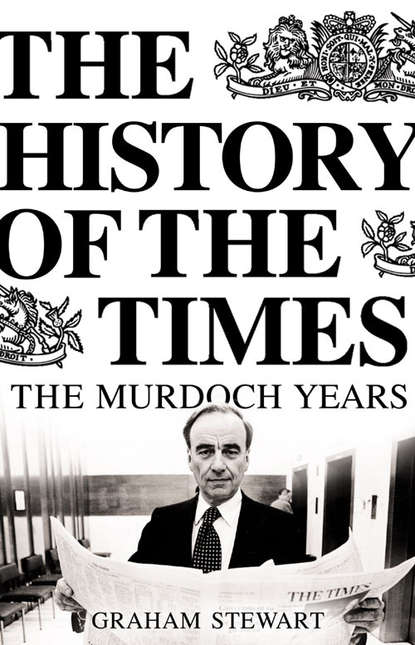

The History of the Times: The Murdoch Years

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Evans now had to face a barrage of jabs and cuts from several directions. Some colleagues, who might have helped absorb the blows, were absent. Emery was hurtling down black runs. The other acting editor over the festive period, Brian MacArthur, had impressed Murdoch and been rewarded with the deputy editorship of the Sunday Times. This was The Times’s loss. Nor did Evans enjoy the loyalty of many who remained. Louis Heren all but denounced him on BBC television. Equally unhappy about the situation over which Evans was presiding, John Grant, the managing editor, threatened to resign. This spurred Douglas-Home to call on Murdoch to tell him that, if Grant left, he too would go. The prospect of losing both the deputy editor and the managing editor spurred Murdoch to depose Evans more quickly than he had intended. The fact that Granada television’s What The Papers Say had just awarded him the title of Editor of the Year was a mere inconvenience.

Donoughue had repeatedly challenged Douglas-Home to prove his loyalty to Evans, and the protestations of allegiance were wearing thin.[281 - Donoughue, The Heat of the Kitchen, pp. 288–9.] Evans was to paint an unflattering picture of his deputy’s behaviour during this period, implying that he was motivated by a self-serving desire to seize the editorship for himself. On the other hand, Evans’s critics thought that when it came to being self-serving, Evans still had questions to answer about his own role in accepting the editorship from someone he had made such concerted attempts to prevent owning the paper.[282 - Spectator, 5 November 1983.] But Douglas-Home’s motives were less clear-cut than the Evans loyalists assumed. Far from being a sycophant towards the proprietor, he was distinctly wary of him. It was what he regarded as Evans’s weakness in the face of Murdoch’s ill temper that disheartened him.[283 - Frank Johnson to the author, interview, 15 January 2003.] There was more than a whiff of snobbery from some of the staff who lined up behind the Eton and Royal Scots Greys Douglas-Home over the northerner and his posse of meritocratic henchmen but a principal belief was that ‘Charlie’ was the man who would stand up to Murdoch, which ‘Harry’ had supposedly failed to do. It was Evans’s misfortune that Murdoch himself now wanted a dose of Douglas-Home as well.

But did Douglas-Home want to work with Murdoch? Far from pulling out all the stops to supplant Evans, he had entered into negotiations to leave The Times for the Daily Telegraph. Notified of this, Evans had begun to look around for a new deputy and had even approached Colin Welch.[284 - Frank Johnson to the author, interview, 15 January 2003.] Welch, who had resigned as the deputy editor of the Telegraph in 1980, was a noted Tory journalist of the intellectual right. If Evans felt Murdoch’s pressure to adopt a more right-wing tone in the paper, then he could not have appeased the proprietor more than by contemplating a prominent role for Welch. Having told Evans of his decision to resign, Douglas-Home proposed postponing his actual leaving until the immediate crisis was over (financially it also made sense to wait until the new tax year in April). In the meantime, he received information that would make him pause further – for a well-placed source assured him that Evans was losing his grip on the situation and would soon be leaving Gray’s Inn Road himself. The source was Evans’s own secretary, Liz Seeber. Given her job description, Seeber was hardly displaying the customary loyalty to her boss, but she had come to the conclusion Evans was presiding over the paper’s collapse and that the only way of saving it was to help Douglas-Home stay in the game. ‘The atmosphere was so unpleasant, it was a dreadful environment to work in’ was how she defended her actions. ‘You had people like Bernard Donoughue permanently in and out of Harry’s office and you just wanted it to be over; it was no longer running a newspaper, it was Machiavellian goings-on.’[285 - Liz Seeber to the author, interview, 18 July 2003.] Douglas-Home later repaid her efforts by giving a book written by her husband a noticeably glowing review.[286 - Philip Howard to the author, interview, 5 December 2002.] But even with this flow of information about what Evans was up to, Douglas-Home still wavered. On the anniversary of Evans’s appointment, Murdoch telephoned Marmaduke Hussey to tell him, ‘I’ve ballsed it up. Harry is going so I’m putting in Charlie.’ Hussey later wrote, ‘I knew that already because Charlie had come to see me the night before and was doubtful whether to accept the job. “For heaven’s sake,” I told him. “I’ve spent five years trying to secure you the editorship – if you want out now I’ll never speak to you again.”’[287 - Hussey, Chance Governs All, p. 179.]

There were certainly some dirty tricks played. Evans loyalists were maintaining that the editor was in a life or death battle to save The Times’s editorial independence from a proprietor bent on imposing his own (increasingly right-wing) views on the paper. This claim was undermined by the leader writer, Geoffrey Smith, who walked into a BBC studio and read out a memo Evans had sent to Murdoch asking for the latter’s view on how the Chancellor’s forthcoming Budget should be presented in the paper. The letter was dynamite but it was between the editor and the proprietor, so why was it being read out for broadcast by a Times leader writer? It was a typed letter and the answer appeared to rest with the holder of the carbon copy. Whether it had touched the intermediary hands of the deputy editor remained a matter for speculation. But one thing was clear: that members of the staff were cheerfully appearing on radio and television alternately to stab or slap the back of their editor was an intolerable situation. For a week, the chaos at The Times dominated the news. Times journalists would gather round the television for the lunchtime news, one half of them cheering Geraldine Norman who would be broadcast condemning Evans, the other half cheering Anthony Holden’s championing of him. Then they would all return to their desks and get on with the job of producing Evans’s newspaper.

Because of their well-placed mole, Evans’s critics had access to more than one incriminating piece of evidence. In a first-year progress report of 21 February, Evans had adopted an excessively ingratiating tone towards Murdoch. ‘Thank you again for the opportunity and the ideas,’ he purred. ‘We are all one hundred per cent behind you in the great battle and I’m glad we’re having it now.’ Evans’s upbeat assessment appeared to offer Murdoch what it could be assumed he wanted. Evans announced that he had approached the right-wing Colin Welch about joining The Times, adding a line that seemed designed to appeal to the Australian’s sociopolitical assumptions, ‘I did talk to Alexander Chancellor but came to the conclusion he represents part of the effete old tired England.’ However, ‘there would be mileage I think in your idea of having some international names (like Dahrendorf, Kissinger, Kristol)’. Regrettably, Evans proceeded to speak ill of past or present colleagues: ‘You’ll perhaps have seen the attack on me in the Spectator for getting rid of “stars” but believe me Hennessy, Berthoud and Berlins they mention were all bone idle. So are many of the others who have gone or are going. It is another part of the old-Times brigade not wanting to work, Louis Heren stirring it up a bit.’[288 - Evans to Murdoch, 21 February 1982, Evans Day File.] The unfortunate tone of this letter tended to support Douglas-Home’s contention that Evans was not always the bulwark for liberty and defender of his staff that his supporters protested him to be.

In fact, if Evans’s tone had been intended to please his proprietor, he was to be sorely disappointed. Two days later, ‘Dear Chairman’ was how he began a huffy note that objected to the ‘cursory comment on the detailed report of our first year which I volunteered to you’. To Murdoch’s criticism that the editorial line had lacked consistency, Evans shot back, ‘You have not, as it happens, made this criticism on several occasions to me but only once (7 January 1982) though I have been made aware of what you have said to other members of the staff when I have not been present.’[289 - Ibid., 23 February 1982, Evans Day File.] When it came to the embattled editor, the proprietor’s heart had turned to stone.

Tuesday 9 March marked the first anniversary of Harold Evans’s appointment as editor. It was hardly a soft news day appropriate for distracting him. It was Budget Day and Evans ensured that The Times covered, reported, reproduced and analysed Sir Geoffrey Howe’s measures in an impressive level of detail. ‘The Chancellor of the Exchequer,’ Evans crooned justifiably to Murdoch afterwards, ‘has gone out of his way to say that the Budget coverage of The Times had restored The Times as a newspaper of record for the first time for many years.’[290 - Ibid., 11 March 1982, Evans Day File.] Written by Donoughue, the leader took a measured view although the front page headline ‘Howe heartens Tories: a little for everyone’ was certainly more positive than the previous year’s assessment. Rab Butler’s death was also front-page news and together with the obituary was accompanied by an article by his one-time acolyte, Enoch Powell. Powell was as insightful as he was admiring of the man thrice denied the opportunity to become Prime Minister. It ‘was mere chance’, he noted, that Butler’s childhood injuries prevented him from serving in either war, ‘but to some of us it was a chance that seemed to match an aspect of his character. He was not the kind of man for whom any cause – not even his own – was worth fighting to the death, worth risking everything.’[291 - Enoch Powell, The Times, 10 March 1982.]

Having only recently returned from his own father’s funeral, Evans was back at Gray’s Inn Road and was just preparing to listen to the Budget speech when he was summoned upstairs to see Murdoch. The proprietor announced he wanted his immediate resignation. He had already asked Douglas-Home to succeed him and Douglas-Home had accepted. According to Evans’s account of the conversation, Murdoch had the grace to look emotional about the situation. Nonetheless he stated his reasons – ‘the place is in chaos’ and Evans had lost the support of senior staff. Evans shot back that it was management’s decisions that had created the chaos and reeled off a list of the senior staff that remained loyal to him. He had no intention of accepting this summary dismissal. Instead he left, refusing to resign, with Murdoch threatening to summon the independent national directors to enforce his departure.[292 - Evans, Good Times, Bad Times, p. 369.]

The independent national directors were supposed to ensure that the proprietor did not put inappropriate pressure on his editor. Instead, Murdoch was threatening to use them as an ultimate force to ensure the editor was removed from the building. Evans had taken the drafting of the editorial safeguards extremely seriously. The following morning he went to seek the advice of one of the independent directors, Lord Robens. The two men met in the Reform Club, Evans confiding his predicament to the ageing Labour peer above the din of a vacuum cleaner engaged in a very thorough once over of their meeting place. Robens considered the matter and suggested that, rather than staying on for six more months of this torture, Evans should go away on holiday. According to Evans’s account, Robens advised, ‘Don’t talk to Murdoch. Leave everything to your lawyer. Relax. We’ll stand by you.’[293 - Ibid., p. 377.] The meeting concluded, Evans strode out from the Reform’s confident classicism into St James’s Park, continually circling the gardens like a yacht with a jammed rudder while he tried to decide whether to fight for his job and the paper’s integrity or to go quietly. Eventually he compromised. He would go noisily.

Back at the office, Evans was received by the unwelcoming committee of Murdoch, Searby and Long who pressed him to announce his resignation before the stand-off created yet more appalling publicity for The Times. But believing there were higher issues at stake, making an issue was precisely Evans’s purpose. The television cameras massed outside Gray’s Inn Road and Evans’s home. His admirers and detractors organized further public demonstrations of support and disrespect while those inside the building tried to put together the paper, unsure whether to take their orders from Evans or Douglas-Home.

The headline for 12 March ran ‘Murdoch: “Times is secure”.’ His threat to close down the paper had been lifted by the agreement with the print and clerical unions to cut 430 full-time jobs (rather than the six hundred requested) and cut around four hundred shifts. Taken together with the savings from switching to cold composition, the TNL wages bill would shrink by £8 million. There would now be one thousand fewer jobs at Gray’s Inn Road than had existed when Murdoch had moved in. This was an extraordinary indictment on the previous owner’s inability to overcome union-backed overmanning. At the foot of the news story appeared the unadorned statement: ‘Mr Harold Evans, the Editor of The Times, said he had no comment to make on reports circulating about his future as editor. He was on duty last night as usual.’[294 - The Times, 12 March 1982.]

In the leader article he wrote, entitled ‘The Deeper Issues’ (some felt this referred to his own predicament), Evans surveyed the panorama of the British disease: the human waste of mass unemployment, the crumbling inner cities, ‘idiot union abuse’, the ‘bored insularity’ of Britain’s approach to its international obligations and the failure of any political party to find answers. There was a scarcely repressed anger from the pen of an editor who had just buried his father – an intelligent and encouraging man for whom the limits of opportunity had confined to a job driving trains. But there were also pointed references to Evans’s own finest hour (the Thalidomide victims) and an attack on ‘the monopoly powers of capital or the trade unions, or too great a concentration of power in any one institution: the national press itself, to be fair, is worryingly over-concentrated’.[295 - ‘The Deeper Issues’, leading article, The Times, 12 March 1982.] There was no need to name names.

Saturday’s Times gave an accurate picture of the situation at Gray’s Inn Road – the report was utterly incomprehensible. Murdoch was quoted as stating ‘with the unanimous approval of the independent national directors’ that Evans had been replaced by Douglas-Home. Lord Robens described this statement as ‘a bit mixed up’. Evans was quoted claiming he had not resigned and his staying on was ‘not about money, as alleged. It is and has been an argument about principles.’ Gerald Long claimed that the independence of the editor had never been in dispute. Holden said it was. Douglas-Home said it wasn’t, going on the record to state:

There has been to my knowledge, and I have worked closely with the editor, absolutely no instruction or vestige of an instruction to the editor to publish or not to publish any political article. There has been no undue pressure to influence the editor’s policy or decisions.[296 - The Times, 13 March 1982.]

Times readers could have been forgiven for believing they were looking not at a news report but at a bleeding gash running down the front page of their paper. During the day, the Journalists of The Times (JOTT) group passed a motion that they released to the press calling for Evans to be replaced by Douglas-Home. They found fault with the ‘gradual erosion of editorial standards’ and Evans’s indecision: ‘The way the paper is laid out and run has changed so frequently that stability has been destroyed.’ Geraldine Norman had been to the fore of getting this motion accepted, much to the disquiet of many of the two hundred subscribing JOTT members whose approval she had not canvassed.[297 - Leapman, Barefaced Cheek, p. 235; Evans, Good Times, Bad Times, pp. 393–4.] A pro-Evans counterpetition was circulated and also attracted support. Nobody wanted another week of this madness.

Meanwhile, Fred Emery had telephoned from the slopes in order to find out what was happening in his absence. Douglas-Home asked him to come back immediately, particularly requesting that he be back in time to edit the Sunday for Monday paper. Emery raced back and found the journalists had become even more polarized during his absence. He also discovered the reason Douglas-Home wanted him back to edit the paper on the Sunday evening. The editor-in-waiting was singing in a choir that evening. In the circumstances, this was a high note of insouciance.

The denouement came the following day, Monday, 15 March, in a series of remarkable twists and turns. Nobody seemed to know whether the editor was staying or going. However, he did periodically emerge to give the impression that he was still in charge. Taking inspiration from a photograph of himself playing tennis, he swung a clenched fist in the air and assured Emery, ‘I play to win!’ Half an hour later, he had tendered his resignation in the curtest possible letter addressed ‘To The Chairman’. It read in its entirety:

Dear Sir,

I hearby tender my resignation as editor of The Times.

Yours faithfully,

H. M. Evans

His colleagues found it easier getting accurate news from the far Pacific than from within the building. All they knew was that Evans had overseen a statement in the early editions of the paper reporting that he had not resigned. They were thus surprised when at 9.40 p.m. he curtly announced to the rolling cameras of News at Ten that he had indeed quit. His decision to give advance warning to ITN in order to maximize the publicity but not his own journalists dampened the send-off he might otherwise have been accorded.[298 - Tim Austin to the author, interview, 4 March 2003; Fred Emery to the author, interview, 24 January 2005.] Instead, when he was sure the cameras were in position, he walked out of the building, stopping only to shake hands with the uniformed guard at the reception desk (unsurprisingly, there was no sign of his secretary). Stopped by a television reporter as he got into the back seat of a waiting car, he refused to make further comment beyond observing, with a weary expression, that it was a tale longer than the Borgias.[299 - ‘The Greatest Paper in the World’, Thames Television, broadcast 2 January 1985.]

VII

Harold Evans came home to a party organized by Tina Brown, his wife. His stalwart supporters came to rally round. Anthony Holden had already created a stir that evening at a function for authors of the year (of which he was one). Seeing Murdoch in the corner of the room he stormed over, almost elbowing the Queen to the ground in the process, and proceeded to harangue the newspaper proprietor. The exchange ended with Murdoch assuring him he would never work on any of his papers again and Holden telling him where he could stick them. Such was the excited gravitation towards this verbal brawl that the Queen found herself momentarily deserted and ignored by the room’s inhabitants.[300 - Anthony Holden to the author, interview, 9 April 2003.] Holden resigned from The Times with immediate effect without taking a penny of compensation. This was a principled stand that impressed Murdoch. Evans, meanwhile, negotiated a pay-off in excess of £250,000. After only one year’s employment, this sum was at the time considered so large that it almost (but not quite) dented Private Eye’s preening glee at his departure in its 26 March edition, unpleasantly entitled and illustrated ‘Dame Harold Evans, Memorial Issue. A Nation Mourns’.[301 - Private Eye, 26 March 1982.]

The generous severance terms did not stop Evans writing Good Times, Bad Times, an account of his struggles at Gray’s Inn Road which was published in 1983. Inevitably, not everyone liked and some did not recognize the picture he painted. His successor as editor, Douglas-Home, refused to read it. He did, however, see enough of the extracts in the press to pronounce, ‘that it presented a quite insurmountable question of inaccuracy’.[302 - Douglas-Home to Michael Leapman, 11 November 1983, Douglas-Home Papers.] The most damaging charges Evans brought both in his book and in subsequent allegations concerned his relations with the proprietor, especially in matters of editorial independence. Evans believed he had incurred Margaret Thatcher’s displeasure and that, in sacking him, Murdoch was enacting a tacit understanding with the Prime Minister as a result of her pressure to ensure his bid for Times Newspapers was not referred to the Monopolies Commission. Perhaps, as Sir John Junor had prophesied to Tina Brown, Murdoch had always intended to sack Evans after a year as soon as he had been the fall guy for unpopular changes Murdoch wanted forced upon the paper.[303 - Evans, Good Times, Bad Times, pp. 177–8.] Such was the regard Evans was held in at the Sunday Times, Murdoch would have had difficulty removing him from that editorship, but switching him next door suited his purposes perfectly.[304 - Evans to the author, interview, 25 June 2003.] Many of the changes Evans effected were those Murdoch had himself wanted to see brought about: redundancies, the paper redesigned with new layout, sharper reporting, more sport and less donnish prevarication as a cover for laziness. On this interpretation of events, Murdoch had used Evans and then flung him overboard.

In Good Times, Bad Times, Evans stated that early in 1982 Murdoch had visited Mrs Thatcher suggesting that she find for Evans a public post so that he could be levered out of the editorship. According to Evans’s account, the Prime Minister had asked Cecil Parkinson, the Conservative Party chairman, to cast around for a job for him and Parkinson had come up with the post of chairman of the Sports Council. Mrs Thatcher, it seemed, was keen to assist Murdoch in finding an easy way to be rid of his turbulent editor.[305 - Ibid.; Evans, Good Times, Bad Times, pp. 1–2.] Evans had caused annoyance by running on his front page a story concerning a letter from Denis Thatcher to the Welsh Secretary written on Downing Street paper (though since this was where he lived, it was not clear what other address he could have given) concerning the slow pace of resolving a planning application made by a subsidiary of a company to which he was a consultant. Most commentators considered undue prominence had been given to a rather minor indiscretion (Mr Thatcher had made clear ‘obviously nothing can be done to advance the hearing’) and even the Times leader on the subject placed it third, where it belonged, below Liberal Party defence policy and political developments in Chad.[306 - The Times, 17 and 18 September 1981.] There was also the question of why Evans had printed a letter that had been stolen from the Welsh Office and touted around by a Welsh news agency. But it hardly necessitated a Thatcher – Murdoch conspiracy to do away with him. Under Evans, The Times had opposed the Government’s obsession with narrow definitions of monetary policy but, as Tony Benn and Michael Foot could attest, it was far from being an outright opponent of the Conservatives. On most issues and in particular on trade union reform, it was supportive. Indeed, had Rees-Mogg continued as editor, it might have been every bit as sympathetic towards the SDP as the measured approach adopted by Evans. And Evans would later make clear both that, had Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands during his watch, The Times would have been stalwart in its support of Britain’s armed liberation of the islands and that the paper would probably have endorsed the Conservatives in the 1983 general election.[307 - Harold Evans to the author, interview, 25 June 2003.] If the Prime Minister wanted the removal of a Fleet Street editor it is hard to see how Evans of The Times could be top of her list. Murdoch asserted that the conspiracy theory was ludicrous, maintaining that he ‘never ever’ discussed getting rid of Evans with Mrs Thatcher. Asked about it in 2004, Cecil Parkinson stated, ‘I cannot remember this incident. I certainly have no recollections of searching for a job for Harold Evans.’[308 - Lord Parkinson to the author, 2 July 2004.] Murdoch doubted that Thatcher and Parkinson had conjured up the Sports Council chairmanship as a way of facilitating Evans’s departure on the grounds that ‘they were not Machiavellian enough’ and adding, ‘I don’t think they cared about The Times. She didn’t.’[309 - Rupert Murdoch to the author, interview, 5 August 2003.]

Did Murdoch interfere in editorial policy? Donoughue disliked hearing that Murdoch thought his leader articles were too generous towards Tory ‘wets’ or Social Democrats.[310 - Donoughue, The Heat of the Kitchen, p. 288.] Evans chose to disregard the proprietor’s expressed hope that The Times would take a critical line on the Civil List.[311 - Evans to the author, interview, 25 June 2003.] Although he certainly gave vent to uncompromising opinions when the conversation turned to political matters, Murdoch always maintained that he had never instructed Evans to take any line in his paper other than one of consistency – a steady course the proprietor claimed was lacking. Douglas-Home was incredulous that Evans could not tell the difference between Murdoch ‘sounding off’ as opposed to giving orders. In Douglas-Home’s experience, Murdoch ‘didn’t object to anyone standing up to him on policy issues’. Of course it was easier for the more robustly right-wing Douglas-Home to find this to be the case. But he went further, claiming that it was Evans who had endangered his own editorial independence by constantly ringing Murdoch for reassurance.[312 - Notes of discussion between Alastair Hetherington and Douglas-Home, 31 October 1983, Douglas-Home Papers.] No subsequent Times editor ever claimed undue pressure was applied by Murdoch on editorial policy. Murdoch did not prevent Frank Giles from pursuing a far more ‘wet’ political line at the Sunday Times, also a paper whose direction Mrs Thatcher might have been expected to take a keen interest in. Murdoch did not stop Giles from being sceptical about Britain seeking to retake the Falklands by force or from being overtly sympathetic towards the SDP in the 1983 general election. It was not for his politics that he was eventually replaced by Andrew Neil, an outsider whom Murdoch believed would breathe new energy into the Sunday title as he had once hoped Evans would do with the daily.

Understandably, Evans’s allegations confirmed the suspicions of all those on the political left who believed Murdoch was a malign influence on news reporting. They had seen it with the Sun and its crude caricature of the left. Now they had evidence that it was consuming The Times. Staged at the National Theatre, David Hare’s 1985 play Pravda – A Fleet Street Comedy was widely interpreted as an attack on Murdoch’s style of proprietorship. Co-written with Howard Brenton whose The Romans in Britain had caused outrage because of its overt depictions of Romans sodomizing Ancient Britons (apparently a metaphor for the British presence in Ulster), Pravda depicted the sorry tale of Lambert La Roux, a South African tabloid owner, buying a British Establishment broadsheet only to sack its editor just after he had received an Editor of the Year award. Anna Murdoch went to see the play. After this, her husband’s only comment on it was to suggest, with a wink, that Robert Maxwell might find it actionable.

But more seriously, if Evans felt he had been improperly treated by Murdoch he could have appealed to the independent national directors to adjudicate on the matter. Given the lengths to which he had gone to write these safeguards into the contract by which Murdoch bought the paper it was surprising that he did not avail himself of the opportunity to challenge the proprietor in this way. Perhaps he thought the independent directors would not support his case. Even Lord Robens, who had spoken supportively to him in an alcove of the Reform Club, was not so stalwart behind his back. According to Richard Searby, Robens promptly told Murdoch that he was the proprietor and if he thought Evans should be sacked, he should be sacked.[313 - Richard Searby to the author, interview, 11 June 2002; similarly rendered in Rupert Murdoch’s interview with the author, 4 August 2003.] Whatever his reasoning, Evans preferred to make his case in a book instead. The audience was certainly wider.

Deeply involved in the union negotiations and in attempting to overcome the production difficulties during Evans’s year in the chair, Bill O’Neill felt that the problem was not one of politics but of personalities. Evans ‘considered himself a creator, an editorial genius’, O’Neill maintained ‘and not someone who would be burdened with incidentals, like the huge losses the title he edited was running. You could not engage Evans in debate. He would agree with everything you put to him.’[314 - Bill O’Neill, Copy Out manuscript.] In his fourteen years as editor of the Sunday Times, Evans had benefited from supportive allies in Denis Hamilton and a proprietor, Roy Thomson, who was happy to invest heavily into ensuring Evans’s creative talents bore fruit. With his move to The Times, he had difficulty adapting to the culture shock of working for a new proprietor who, after initially encouraging further expansion, suddenly demanded urgent economies in order to keep the title afloat. Hamilton’s disillusion and departure also robbed him of a calming and understanding influence. Evans complained that ‘every single commercial decision of any importance was taken along the corridor in Murdoch’s office, while we went through our charades’ on the TNL board.[315 - Evans, Good Times, Bad Times, p. 312.] But what did he expect? Who was writing the cheques? It was as if Evans had confused editing the newspaper with owning it. As Evans proved at the Sunday Times and in his subsequent career in New York (to where he and Tina Brown decamped), he was at his best when he had a generous benefactor prepared to underwrite his initiatives. Especially in the dark economic climate of 1981–2, Murdoch was not in the mood to be a benefactor.

Indeed, if Evans was a victim of Murdoch’s ruthless business sense, he was most of all a victim of the times. The dire situation of TNL’s finances meant Murdoch was frequently in Gray’s Inn Road and was particularly watchful over what was going on there. Furthermore, Murdoch and his senior management could hardly absolve themselves totally of their part in the chaos surrounding Evans’s final months in the chair. Murdoch had told Evans to bring in new blood and frequently suggested expensive serializations to run in the paper. When the costs of these changes reached the accounts department he then blamed Evans for his imprudence.[316 - Evans to the author, interview, 25 June 2003.] The failure to agree with the editor a proper budget allocation compounded these problems, although Murdoch refuted Evans’s claims that he did not know what the financial situation was, maintaining he ‘got budgets all the time’.[317 - Rupert Murdoch to the author, interview, 4 August 2003.] The swingeing cuts in TNL clerical staff had to be made, but the brinkmanship necessary to bring them about created a level of tension that clearly had negative effects on morale within the building. Murdoch’s own manner at this time, frequently swearing and being curt to senior staff, contributed to the unease and feeling of wretchedness.[318 - Anthony Holden to the author, interview, 9 April 2003.] As the years rolled by with the financial and industrial problems of News International receding while he developed media interests elsewhere, so Murdoch spent less time living above the Times shop. Therefore, if Evans wanted to be left to his own devices, it was his misfortune to have accepted the paper’s editorship at the worst possible moment. Had he been appointed later, at a time when the paper was no longer enduring a daily fight for survival and justification of every expense was no longer necessary, he might have proved to be a long serving and commercially successful Times editor. This, after all, was what became of his protégé, Peter Stothard.

Rees-Mogg took the view on his successor’s downfall that an editor could fall out with his proprietor or several of his senior staff but not with both at the same time.[319 - Rees-Mogg, ‘The Greatest Paper in the World’, Thames Television, broadcast 2 January 1985.] In the eyes of the old guard, Evans had two principal problems. First, he frequently changed his mind. This had all been part of the creative process when he had edited a Sunday paper, since he had a week to finalize his position, but it made life on a daily basis extremely difficult. The second irritation was that he surrounded himself with his own people who were not, in heart and temperament, ‘Times Men’. For this reason, Donoughue and Holden were disliked in a reaction that overlooked their considerable talents. In the closing months of the drama, Holden would periodically arrive at his office to find childish sentiments scrawled on his door. Invariably they were of an unwelcoming nature.[320 - Anthony Holden to the author, interview, 9 April 2003.] Indeed, the pro-Evans petition circulated in the dying moments of his tenure demonstrated perfectly the essential rift between The Times old guard and Evans’s flying circus of new recruits. Six of the thirteen senior staff members signed the pro-Evans petition (the other seven were either absent or pointedly refused to endorse him). But of Evans’s six senior supporters, five had been recruited by him from outside the paper in the course of the past year. Only one of the seven who did not sign had worked for The Times for less than twelve years.[321 - Sunday Times, 14 March 1982.]Good Times, Bad Times concentrated on Murdoch as the assassin. But at the moment of impact there were plenty of other bullets flying from a plethora of vantage points.

Tony Norbury, able to speak from the vantage point of over forty years experience on the production side of the paper, believed that although Evans’s demise was inevitable and perhaps necessary, he was nonetheless ‘the Editor who saved The Times’.[322 - Tony Norbury to the author, interview, 27 April 2004.] In the space of a year, he had brought about great changes and many of them were for the better. The layout was much improved. Circulation was up by 19,000 on the comparable period in 1980. The paper was revitalized. It was no longer in retreat. Probably his greatest legacy was those journalists he brought in who stayed with the paper in the years ahead, among whom Peter Stothard, Frank Johnson, Miles Kington and the medical correspondent, Dr Thomas Stuttaford, were to loom large. Indeed, it would be quite wrong to assume that the old guard were necessarily right in opposing Evans’s innovations. Their victory over him in March 1982 was personal and vindictive. It was also temporary. Much of what he attempted to teach the paper about ‘vertical journalism’ would, in time and in a less frenetic environment, eventually be accepted and adopted.

It was Evans’s other concept, the ‘editing theory of maximum irritation’, that did for him. As one of the senior financial journalists snootily put it, ‘What is this silly little man doing running around trying to tell us how to do our jobs?’[323 - Quoted in Donoughue, The Heat of the Kitchen, p. 287.] Evans’s mistake was to make too many radical changes too quickly and in a manner that left old Times journalists feeling excluded. His attempts to make the paper more like its more popular Sunday neighbour were especially disliked. A critic at the Spectator found fault that ‘instead of spending the morning in Sir William [Rees-Mogg’s] musty but absorbing library we should be outside “in the field” with Mr Evans getting down to what a French investigative reporter once termed “the nitty grotty”. It’s all lead poisoning from petrol fumes nowadays, and why not? Only that several other papers tell us about that sort of thing all the time.’[324 - Patrick Marnham, Spectator, 20 February, 1982.] While the Sunday Times was a ‘journalists paper with a high-risk dynamic’ to break news, The Times ‘must get its facts and opinions right’ and its editor ‘must possess great steadiness and consistency … He must be patient and move slowly.’[325 - Paul Johnson, Spectator, 20 March 1982.] Or, as Philip Howard put it, ‘The Sunday Times and The Times are joined by a bridge about ten yards long and somewhere along that bridge Harry fell off.’[326 - Philip Howard, ‘The Greatest Paper in the World’, Thames Television, broadcast 2 January 1985.]

One of the few journalists brought in by Evans who did not support him in his time of trial was Frank Johnson. ‘I cannot think of a better thing I did in 1981 than ask you to join The Times,’ Evans wrote to congratulate him when he was named Columnist of the Year at the British Press Awards.[327 - Evans to Frank Johnson, 12 March 1982, Evans Day File.] But Johnson, who had always admired the old Times, was relieved when Douglas-Home took over. With Murdoch’s threat to close the paper lifted and Evans, Holden and Donoughue seeking alternative employment, the atmosphere at Gray’s Inn Road improved remarkably swiftly. Douglas-Home, the editor most of the senior staff had wanted in the first place (and but for Murdoch would probably have got), was at last in the chair. But what buried the internecine bickering most decisively was a major incident in – of all unlikely places – the South Atlantic. As Britain’s armed forces sailed towards the Falkland Islands and an uncertain fate, office politics suddenly looked self-indulgent and thoughts switched back to the job everyone was paid to do – report the news.[328 - Frank Johnson to the author, interview, 15 January 2003.]

CHAPTER THREE

COLD WARRIOR

The Falklands War; the Lebanon; Shoring up NATO; Backing Maggie

I

The journalists of the Buenos Aires Siete Dias had a commendable knowledge not only of their government’s intentions but also of how The Times of London liked to lay out its front page. Forty-eight hours before the invasion began Siete Dias’s readers were presented with an imaginary front page of that morning’s edition of The Times. It was good enough to pass off as the real thing. The masthead and typeface were accurate. Even the headline ‘Argentinian Navy invades the Falkland Islands’ was grouped across the two columns’ width of the lead report rather than stretched across the whole front page. That was a particularly observant touch. The accompanying photograph of advancing Argentine troops was also in exactly the place the page designers of Gray’s Inn Road would have put it – top centre right with a single-column news story hemming it back from the paper’s edge. Someone, at least, had done his homework.

The real Times of London for that day had an almost identical front-page layout. The only visual difference was that the lead headline announced ‘Compromise by Labour on abolition of Lords’ – which could have been confidently stated at almost any time in the twenty years either side of 31 March 1982. But the perceptive reader would have noticed something more portentous in the adjacent single column headlined ‘British sub on the move’. The story, ‘By Our Foreign Staff’, claimed that the nuclear-powered hunter-killer submarine, HMS Superb ‘was believed to be on its way’ to the Falkland Islands although the Royal Navy ‘refused to confirm or deny these reports’. This was odd. The Times was not in the habit of knowing, let alone announcing, the sudden change of course of a British nuclear submarine. In fact, the story had been planted. It was intended to warn the government in Buenos Aires that their invasion intentions had been discovered. But it was too late. The Argentinian troops had already boarded the vessels. The aircraft carrier Veinticinco de Mayo had put out to sea.

In the aftermath of a war that caused the deaths of 255 Britons and 746 Argentinians, questions were asked about why London failed to perceive the threat to the Falkland Islands until it was too late. The press had not seen it coming. But they could hardly be blamed when Britain’s intelligence community had also failed to pick up on the warning signs. In retrospect, the Government’s dual policy of dashing Argentina’s hopes of a diplomatic solution while announcing a virtual abandonment of the islands’ defence appeared like folly on a grand scale.

Despite talk of there being oil, there had long been little enthusiasm in the Foreign Office for holding onto the barren and remote British dependency, eight thousand miles away and important primarily for the disruption it caused Britain’s relations with Argentina, a bulwark against South American Communism where much British capital was invested. The general impression was given that if Buenos Aires wanted the islands that much, they could have them. But the will of the 1800 islanders, stubborn and staunchly loyal subjects of Her Majesty, complicated the matter. In November 1980, Nicholas Ridley, a Foreign Office minister, thought he had the answer when he suggested transferring the islands’ sovereignty formally to Argentina while leasing back tenure in the short term so that the existing islanders would not be handed over to an alien power effectively overnight. This idea had been broadly supported in a third leader in The Times, written by Peter Strafford, albeit on the condition the Falkland islanders agreed to it.[329 - John Grigg, The History of The Times, vol. VI: The Thomson Years, p. 549.] They lost no time in making clear they did not. Their opposition emboldened Margaret Thatcher and the House of Commons, sceptical of the ‘Munich tendency’ within the Foreign Office, to dismiss the proposal out of hand.

Argentina was a right-wing military dictatorship. During the 1970s ‘dirty war’, its ruling junta had murdered thousands of its citizens. If the British Government was determined to close the diplomatic door over the islands’ sovereignty to such a regime it might have been advisable to send clear messages about London’s determination to guard the Falklands militarily. Yet, this is not what happened. The public spending cuts of Margaret Thatcher’s first term did not bypass the armed forces. In 1981, John Nott, the Defence Secretary, proposed stringent economies. Guided by Henry Stanhope, the defence correspondent, The Times had argued that if there had to be cuts it would be better for the greater blow to fall upon the British Army of the Rhine rather than the Royal Navy since the BAOR’s proportionate contribution to the NATO alliance was not as significant as the maritime commitment. Yet, when Nott’s spending review was published in June, he proposed closing the Chatham dockyards and cutting the number of surface ships. One of those vessels was HMS Endurance, which was to be withdrawn from its lonely patrol of the South Atlantic.

Although it was understandably not described as such, the Endurance was Britain’s spy ship in the area – as the Argentinians had long assumed. But for those who did not look beyond its exterior, it appeared too lightly defended to put up much resistance to an Argentine assault. Consequently, scrapping the ship appeared to make sense in every respect other than the psychological signal it transmitted to Buenos Aires. It was a fatal economy. Britain appeared to be dropping its guard over the Falkland Islands. The junta saw its chance. Only a small but prophetic letter, from Lord Shackleton, Peter Scott, Vivian Fuchs and five other members of the Royal Geographical Society, printed in The Times on 4 February 1982, pointed out the strategic short-sightedness of withdrawing the only white ensign in the South Atlantic and Antarctic seas.[330 - From Lord Shackleton and others, letters to the editor, The Times, 4 February 1982.] The paper did not pick up on the point.

To be fair, there were remarkably few early warning signs. General Leopoldo Galtieri’s inaugural speech as Argentina’s President in December 1981 contained no reference to reclaiming ‘Las Malvinas’. The first indication Times readers received that all was not well came on 5 March 1982 when Peter Strafford reported that Buenos Aires was stepping up the pressure over the islands. Strafford speculated that with the Falklands defended by a Royal Marines platoon and local volunteers – a total of less than one hundred men – an invasion was possible ‘as a last resort’. But it seemed far more likely that Buenos Aires would apply pressure through the United Nations or by threatening to sever the only regular air service out of the islands which was operated by the Argentine Air Force.

It was not until 23 March that The Times again focused its attention firmly on developments when it reported the Foreign Office’s confirmation that an illegal detachment of about fifty Argentinians claiming to have a contract to dismantle the whaling station at Leith on South Georgia, a British dependency eight hundred miles south-east of the Falklands, had hoisted their national flag. The Foreign Office was quoted as reacting ‘sceptically to the suggestion that the landing on South Georgia last week was instigated by the Argentine Government’.[331 - The Times, 23 March 1982.]

Whitehall could not be expected to dispatch the Fleet every time a trespasser waved his national flag on some far-off British territory. In the same month in which the ‘scrap metal merchants’ were posing for photographs on the spectacularly inhospitable and all but uninhabited South Georgia, Thomas Enders, the US Assistant Secretary of State for Latin America, had visited President Galtieri and passed on to the British Foreign Office Minister Richard Luce the impression that there was no cause for concern. Nonetheless, Margaret Thatcher asked for contingency plans to be drawn up and for a reassessment of the Joint Intelligence Committee’s existing report on the invasion threat to the Falklands. It was too late. On the evening of 31 March, John Nott passed to the Prime Minister the appalling news: an intelligence report that an Argentine armada was at sea and heading straight for the Falklands. Their estimated date of arrival was 2 April.[332 - Peter Hennessy, The Prime Minister, p. 413.]

The Times had already reported, on the front page for Monday 29 March, ‘five Argentine vessels were last night reported to be in the area of South Georgia’. The second leading article that day, ‘Gunboat or Burglar Alarm?’, warned that the Falklands were probably the real target. It attempted to marry the diplomatic tone taken when the leader column had last addressed the subject in November 1980 that the islanders’ future ‘can only be on the basis of an arrangement with their South American neighbours’ with a belated note of half-warning, ‘Britain should help them get the best arrangement possible, and to do that should be prepared to put a military price on any Argentine smash-and-grab raid’.[333 - ‘Gunboat or Burglar Alarm?’, leading article, The Times, 29 March 1982.] Tuesday’s front page reported that ‘two other Argentine naval vessels were said to have left port’ but that London was still making no official comment. The following day came the leaked report that a nuclear submarine was on its way to the Falklands. On Thursday 1 April, the paper conveyed accurately the atmosphere in the Gray’s Inn Road newsroom with a headline that ought to have become famous in its field: ‘Impenetrable silence on Falklands crisis’.

Apart from some ‘library pictures’ of the Falkland Islands’ capital, Port Stanley, and rusting hulks in South Georgia’s Grytviken harbour, it was not possible to accompany the unfolding saga with ‘live’ pictures. There was no press cameraman on the islands. However, the Sunday Times had dispatched Simon Winchester to follow up on the South Georgia ‘scrap metal merchants’. Winchester was in Port Stanley when the Argentine forces landed. On 2 April, The Times was able to use his copy, announcing that the invasion was expected any moment and citing the state of emergency alert broadcast to the islanders by their Governor, Rex Hunt. It made for dramatic reading. Ironically, while a paper like The Times, famed for its correspondents in far flung places had not got round to getting a reporter in situ, the Sun – not celebrated for its foreign desk or international postings – did have a man there. Its reporter, David Graves, had set off for South Georgia on his own whim. He too was in Stanley when the shooting started.[334 - Peter Chippindale and Chris Horrie, Stick It Up Your Punter, pp. 128–31.] Unfortunately, neither journalist would be filing from there for much longer. Both Winchester and Graves had to move to the Argentine mainland. There, Winchester, together with Ian Mather and Tony Prime of the Observer were arrested on spying charges. Over the next few weeks, the British media was put in the impossible position of trying to report what was happening on a group of islands where they had no reporters.