По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

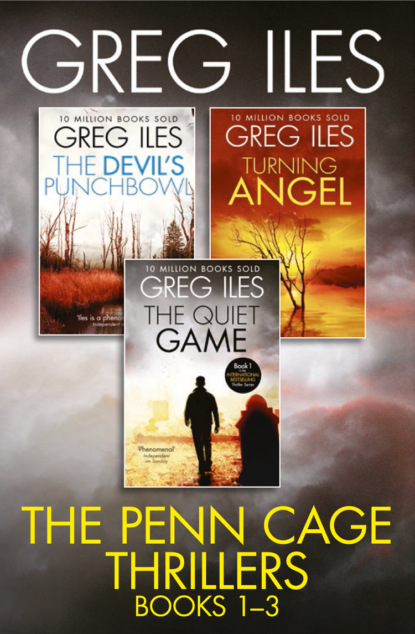

Greg Iles 3-Book Thriller Collection: The Quiet Game, Turning Angel, The Devil’s Punchbowl

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The vacation is over. And when the vacation is over, you go home. But where is home? Technically Houston, the suburb of Tanglewood. But Houston doesn’t feel like home anymore. The Houston house has a hole in it now. A hole that moves from room to room.

The thought of Penn Cage helpless would shock most people who know me. At thirty-eight years old, I have sent sixteen men and women to death row. I watched seven of them die. I’ve killed in defense of my family. I’ve given up one successful career and made a greater success of another. I am admired by my friends, feared by my enemies, loved by those who matter. But in the face of my child’s grief, I am powerless.

Taking a deep breath, I hitch Annie a little higher and begin the long trek back to the monorail. We came to Disney World because Sarah and I brought Annie here a year ago—before the diagnosis—and it turned out to be the best vacation of our lives. I hoped a return trip might give Annie some peace. But the opposite has happened. She rises in the middle of the night and pads into the bathroom in search of Sarah; she walks the theme parks with darting eyes, always alert for the vanished maternal profile. In the magical world of Disney, Annie believes Sarah might step around the next corner as easily as Cinderella. When I patiently explained that this could not happen, she reminded me that Snow White rose from the dead just like Jesus, which in her four-year-old brain is indisputable fact. All we have to do is find Mama, so that Daddy can kiss her and make her wake up.

I collapse onto a seat in the monorail with a half dozen Japanese tourists, Annie sobbing softly into my shoulder. The silver train accelerates to cruising speed, rushing through Tomorrowland, a grand anachronism replete with Jetsons-style rocket ships and Art Deco restaurants. A 1950s incarnation of man’s glittering destiny, Tomorrowland was outstripped by reality more rapidly than old Walt could have imagined, transformed into a kitschy parody of the dreams of the Eisenhower era. It stands as mute but eloquent testimony to man’s inability to predict what lies ahead.

I do not need to be reminded of this.

As the monorail swallows a long curve, I spy the crossed roof beams of the Polynesian Resort. Soon we will be back inside our suite, alone with the emptiness that haunts us every day. And all at once that is not good enough anymore. With shocking clarity a voice speaks in my mind. It is Sarah’s voice.

You can’t do this alone, she says.

I look down at Annie’s face, angelic now in sleep.

“We need help,” I say aloud, drawing odd glances from the Japanese tourists. Before the monorail hisses to a stop at the hotel, I know what I am going to do.

I call Delta Airlines first and book an afternoon flight to Baton Rouge—not our final destination, but the closest major airport to it. Simply making the call sets something thrumming in my chest. Annie awakens as I arrange for a rental car, perhaps even in sleep sensing the utter resolution in her father’s voice. She sits quietly beside me on the bed, her left hand on my thigh, reassuring herself that I can go nowhere without her.

“Are we going on the airplane again, Daddy?”

“That’s right, punkin,” I answer, dialing a Houston number.

“Back home?”

“No, we’re going to see Gram and Papa.”

Her eyes widen with joyous expectation. “Gram and Papa? Now?”

“I hope so. Just a minute.” My assistant, Cilla Daniels, is speaking in my ear. She obviously saw the name of the hotel on the caller-ID unit and started talking the moment she picked up. I break in before she can get rolling. “Listen to me, Cil. I want you to call a storage company and lease enough space for everything in the house.”

“The house?” she echoes. “Your house? You mean ‘everything’ as in furniture?”

“Yes. I’m selling the house.”

“Selling the house. Penn, what’s happened? What’s wrong?”

“Nothing. I’ve come to my senses, that’s all. Annie’s never going to get better in that house. And Sarah’s parents are still grieving so deeply that they’re making things worse. I’m moving back home for a while.”

“Home?”

“To Natchez.”

“Natchez.”

“Mississippi. Where I lived before I married Sarah? Where I grew up?”

“I know that, but—”

“Don’t worry about your salary. I’ll need you now more than ever.”

“I’m not worried about my salary. I’m worried about you. Have you talked to your parents? Your mother called yesterday and asked for your number down there. She sounded upset.”

“I’m about to call them. After you get the storage space, call some movers and arrange transport. Let Sarah’s parents have anything they want out of the house. Then call Jim Noble and tell him to sell the place. And I don’t mean list it, I mean sell it.”

“The housing market’s pretty soft right now. Especially in your bracket.”

“I don’t care if I eat half the equity. Move it.”

There’s an odd silence. Then Cilla says, “Could I make you an offer on it? I won’t if you never want to be reminded of the place.”

“No … it’s fine. You need to get out of that condo. Can you come anywhere close to a realistic price?”

“I’ve got quite a bit left from my divorce settlement. You know me.”

“Don’t make me an offer. I’ll make you one. Get the house appraised, then knock off twenty percent. No realtor fees, no down payment, nothing. Work out a payment schedule over twenty years at, say … six percent interest. That way we have an excuse to stay in touch.”

“Oh, God, Penn, I can’t take advantage like that.”

“It’s a done deal.” I take a deep breath, feeling the invisible bands that have bound me loosening. “Well … that’s it.”

“Hold on. The world doesn’t stop because you run off to Disney World.”

“Do I want to hear this?”

“I’ve got bad news and news that could go either way.”

“Give me the bad.”

“Arthur Lee Hanratty’s last request for a stay was just denied by the Supreme Court. It’s leading on CNN every half hour. The execution is scheduled for midnight on Saturday. Five days from now.”

“That’s good news, as far as I’m concerned.”

Cilla sighs in a way that tells me I’m wrong. “Mr. Givens called a few minutes ago.” Mr. Givens and his wife are the closest relatives of the black family slaughtered by Hanratty and his psychotic brothers. “And Mr. Givens doesn’t ever want to see Hanratty in person again. He and his wife want you to attend in their place. A witness they can trust. You know the drill.”

“Too well.” Lethal injection at the Texas State Prison at Huntsville, better known as the Walls. Seventy miles north of Houston, the seventh circle of Hell. “I really don’t want to see this one, Cil.”

“I know. I don’t know what to tell you.”

“What’s this other news?”

“I just got off the phone with Peter.” Peter Highsmith is my editor, a gentleman and scholar, but not the person I want to talk to just now. “He would never say anything, but I think the house is getting anxious about Nothing But the Truth. You’re nearly a year past your deadline. Peter is more worried about you than about the book. He just wants to know you’re okay.”

“What did you tell him?”

“That you’ve had a tough time, but you’re finally waking back up to life. You’re nearly finished with the book, and it’s by far the best you’ve ever written.”

I laugh out loud.