По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

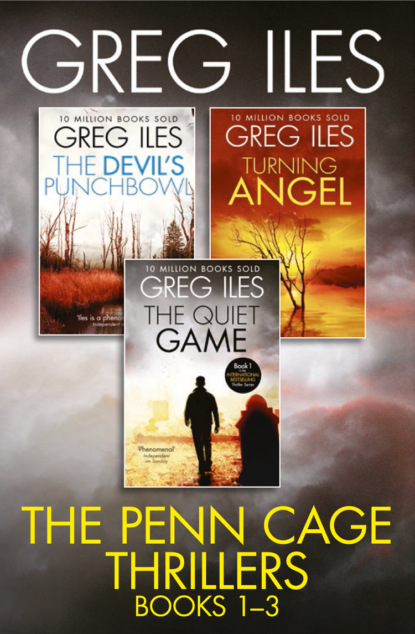

Greg Iles 3-Book Thriller Collection: The Quiet Game, Turning Angel, The Devil’s Punchbowl

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

His head bobs once. Then I hear soft laughter, an ironic chuckle.

“Did you?”

“My mother was a maid.”

He glances at me from the corner of his eye, then looks back into his glass. Embarrassment is not exactly what I feel. It’s more like mortification. I’m trying to think of how to apologize when he says, “Nothing wrong with being a maid. It’s honest work. Like soldiering.”

I want to hug him for that.

“How long did Ruby work for your family?”

“Thirty-five years. She came when I was three.”

“That’s a long time.”

“And she burned to death. Because of what I’m doing, she burned to death.”

Kelly rotates his stool and puts his foot on a crosspiece of mine. “Can I ask you something?”

“Sure.”

“Why are you doing what you’re doing?”

“The truth? I don’t know. In the beginning I wanted to nail a guy who hurt my father a long time ago. And me.” I take another shot of Scotch, and this one brings sweat to my skin. “That’s a bad reason, I guess.”

“Not so bad.”

“It’s not worth Ruby’s life.”

“No. But that’s not the only reason you’re doing it. You’re trying to set a murder right. And from what I can tell, it needs setting right. I’ve watched you these last few days. You’re a crusader. I knew some in the service, and you’re one of them. I’ve got a feeling you saw some horrible atrocity when you were young. A race murder or something. Something that’s weighed you down a long time.”

“No. I never saw anything like that. Not much of that happened around here, to tell you the truth.”

I swallow the remainder of my Scotch and signal the bartender for a refill. “What I do remember … it probably won’t sound like anything. I was in the fourth grade when integration started here. I was in the public school then. The first semester they sent twenty black kids into our school. Five. Into an all-white elementary school. The black kid in my grade was named Noble Jackson. Nobody was horrible to those kids. Not overtly. But every day at recess, we’d be out there playing ball or whatever, and Noble Jackson would be standing off at the edge of the playground by himself. Just standing there watching us. Excluded. I guess he tried to play the first couple of days, and nobody picked him for anything. Every day he just stood there by himself. Staring, kicking rocks, not understanding. The next semester my parents moved me to St. Stephens.”

The Scotch has soured in my stomach. “Now that I’m older, I know that kid’s parents made a conscious decision to do something very hard. Something my parents wouldn’t do. They risked their child’s education, maybe even his life, put him into a situation where it would be almost impossible for him to learn because of the pressure. They did that because somebody had to do it. When I think of that kid, I don’t feel very good. Because exclusion is the worst thing for a child. It’s a kind of violence. And the effects last a long time. I think maybe Noble Jackson is part of the reason I’m doing this.”

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: