По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

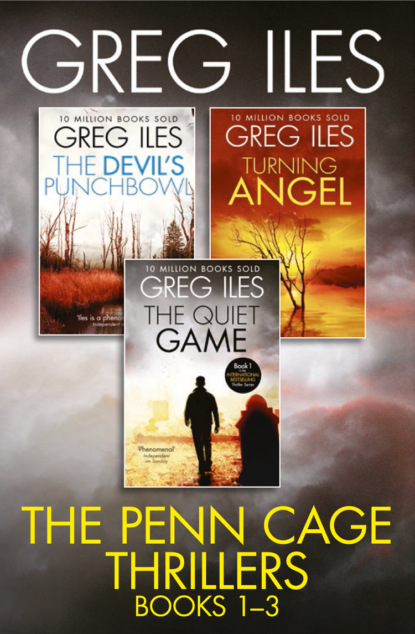

Greg Iles 3-Book Thriller Collection: The Quiet Game, Turning Angel, The Devil’s Punchbowl

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“I know you lied about the dynamite. You planted those blasting caps. I also know the murder wasn’t your idea.”

The eyes blink slowly in the shadows, like a snake’s. “You don’t know shit.”

“You’ll find out different on Wednesday.”

The shotgun barrel moves closer to me. “You can’t prove I killed that nigger, because I didn’t kill him.”

“Come on, Ray. What’s the point in lying now?”

He chuckles softly. “You know how people say, ‘That boy don’t know nothing’? Well, you don’t even suspect nothing.”

“If you’ll tell the D.A. how the Payton murder really went down—if you’ll give up Marston—I’ll get the D.A. to grant you full immunity.”

“Immunity for murder.”

“Your testimony would force Marston to plead guilty. If Leo cuts a deal, it saves the city the embarrassment of a public trial for a race murder. That’s what the powers-that-be want.”

“Rat out Judge Marston.”

“And John Portman.”

A short bark of a laugh. “Boy, you’re so goddamn stupid I’m surprised you made it through law school. What you think Portman had to do with anything?”

“I don’t know. But I know he’s scared enough to try to kill you to keep you quiet.”

A nerve twitches in Presley’s left cheek. “That weasel. He wasn’t shit in sixty-eight.”

“He is now. And he’ll try again. He’s got too much to lose. Cut a deal, you short-circuit the whole trial. It’ll all be over before Portman knows what hit him.”

Presley waves the shotgun furiously. “You think I give a fuck if that trial happens? What do I care if the niggers run wild in the streets? Let the goddamn bleeding hearts see what happens when there ain’t nobody like me around to keep the jungle bunnies in line.”

He turns his head and spits through a narrow door, which I hope is the bathroom. Then he says, “You’re working with a nigger on this, ain’t you?”

“You mean Althea Payton?”

“Shit, no. That nigger deputy, Ransom.”

“Don’t know him.”

“Don’t try to lie, boy. You ain’t had the practice. That Ransom ain’t right in the head. Never has been, since the army. He did dope and turned on his own people. He sucked that bottle like a tit for twenty years. The boy can’t hardly function without a football in his hand. You ever ask yourself why he wants Marston so bad?”

I say nothing.

“I knew Ike when he was with the P.D. His old shit will drag him down quick as it will me.”

“You’re not listening, Ray. If I’m forced to put on my case, you’ll be indicted for murder before sundown Wednesday. I guarantee it.”

Presley squints at me as though measuring me for a shroud. “You keep pushing for that trial, you won’t live to see Wednesday. And that fag bodyguard you got out there won’t be able to help you none.”

“Who’s going to kill me? You?”

“Me? I ain’t leaving this trailer.”

“Do the deal, Ray. It’s your only chance.”

“Me and the judge go back thirty years. I ain’t no punk to roll over on my friends.”

“You think Leo Marston is your friend?”

He jabs the shotgun at me. “I know you ain’t.”

The blonde’s eyes track me over the sights of her rifle, all the way to the door. I shouldn’t say another word, but Ruby’s blood is calling to me from the ground.

“Where were you Tuesday afternoon, Ray?”

He cuts his eyes at the blonde, then looks back at me, a smug light in his eyes. “I believe I was delivering a message in town.”

“A message,” I repeat, recalling the flames eating through the roof of our house, the smell of Ruby’s cooking flesh. My hands ball into fists at my sides.

“I don’t think it got received, though,” he says.

I step within two feet of him. “I’m going to settle that score, you piece of shit. You’re going to die in the Parchman infirmary. They don’t stock your Mexican cocktail there. And there aren’t any blondes to take the edge off, as you like to put it. Not girls, anyway.”

His thin lips part in a predatory smile, revealing small white teeth. “You’ll be dead before I will. It’s coming now, and you don’t even see it.”

When I open the door, the sun hits my eyes like a flash-bulb, but it feels good to get out of the stinking trailer.

Kelly is standing by the cars. “Accomplish anything?”

“No.”

When I reach the cars, he pats me on the shoulder. “Let’s go back to town, boss.”

One of the things that has always separated Natchez from other Mississippi towns is that if you want a drink you can get it, no matter the day or hour.

Kelly suggests the Under the Hill Saloon (a national treasure of a bar), but a big crowd gathers there on Sundays to watch the sun set over the river, and they start celebrating early.

A crowd is not what I want right now.

The bar at Biscuits and Blues is oak and runs a good thirty feet down one wall, with a mirror behind it and glittering bottles and glasses stacked in front. The restaurant is empty but for a couple eating in a booth against the wall opposite the bar. Clanks and clatters filter through the heavy kitchen doors, but otherwise the atmosphere is perfect.

I order Scotch, Kelly the same. Our reflections watch us from the mirror behind the bar like solemn relatives visiting from a cold northern country. When the whisky comes, I swallow a shot big enough to steal my breath, then wipe my mouth on my jacket sleeve. Kelly sips with a deep centeredness, like a man who has known life without luxuries and wants to savor them while he can. He doesn’t talk. He doesn’t look at me. He stares through the bottom of his glass, as though pondering the grain of the wood beneath. Yet I am certain that every movement in the restaurant—even on the street outside—registers on his mental radar. Kelly is covering me even now.

“Kelly?”

“Mm?”

“Did you have a maid when you grew up?”