По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

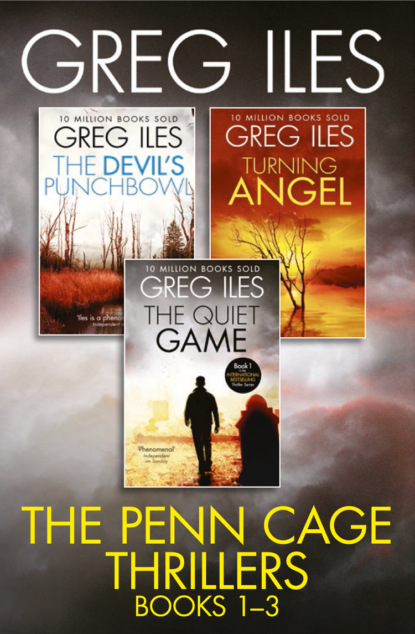

Greg Iles 3-Book Thriller Collection: The Quiet Game, Turning Angel, The Devil’s Punchbowl

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“It’s not sex, Caitlin. It’s money or power. That’s what Marston lives for.”

She sighs and gets up, then drops her left hand on the charred box of files. “I hope there’s something in here.”

“You’ve got to remember one thing. I’m treating this like a murder case, but it’s not. It’s a civil case.”

“So?”

“So the standard of proof is lower. I don’t have to prove Marston’s guilt to twelve people beyond a reasonable doubt. I have to convince nine jurors that it’s more likely than not that Marston was involved in the Payton murder. That means a fifty-one percent certainty. And the jury won’t have to agonize over their decision the way a criminal jury would. Because their verdict won’t send Marston to jail or to a gurney for lethal injection. Another jury will get that job.”

Caitlin moves toward the door. “I think you’re going to have a hell of a job convincing those nine people unless you figure out why Marston would want Payton dead. And prove it.”

When she opens the door, the goateed anarchists pop through it with their sleeves rolled up and smirks on their faces.

“Mulder and Scully reporting for duty,” says one.

Caitlin shakes her head and walks out, leaving me to deal with my new assistants.

In the forty hours between the end of my lecture on Friday and dawn on Sunday, we built a circumstantial case against Leo Marston. The only sleep I got was brief naps on the couch in Caitlin’s office, taken while reporters, photographers, and interns worked in shifts over the boxes of Marston papers that arrived in desultory waves from storage rooms unknown. Only my anarchists—who did have actual names, Peter and Ed, prosaically enough—kept pace with me during this marathon. They seemed to see it as a holy mission, one in which iconoclasts could cheerfully take part.

Daniel Kelly moved through the building like the ghost at the feast, making wry observations, delivering coffee, and disappearing for brief reconnaissance patrols, which he called “checking the perimeter.” Whenever Caitlin left the building to cover a story, Kelly went with her. The police scanner in her office enabled her to reach the scene of several racial altercations before the cops did. Most of these involved two or three individuals, and broke out in stores or restaurants, where inflammatory language was easily overheard. On two occasions these fights escalated into brawls, and Kelly proved his value both times by protecting Caitlin with his rather alarming skills.

Saturday morning, Ed the anarchist decided we needed fresh inspiration, so he sat down with a computer and inkjet printer and went to work. An hour later, he walked into the conference room wearing a T-shirt with NAIL BOSS HOG emblazoned across the chest in red. I found it hard to believe that Ed had ever watched an episode of The Dukes of Hazzard, but he assured me he’d followed it religiously as a child growing up in Michigan, and that most of his ideas about the South had been formed by this grotesque television show. By afternoon, half the Examiner staff was wearing NAIL BOSS HOG shirts, and their galvanizing effect was undeniable. Even Caitlin popped into the conference room wearing one.

But the work itself was tedious and exhausting. The master map that guided us on our paper journey into Marston’s past was his 1997 tax return. It listed most of his business holdings (the number of Schedule C’s and E’s was astounding), and I immediately began drafting a supplemental request for production using these as a guide. His form 1040 showed an adjusted gross income of over two million dollars for 1997, and the sheer variety of his holdings was staggering. Real estate, manufacturing, banking, timber. And despite the moribund oil business, he had recently struck a significant gas field in south Texas. What fascinated me was the variety of small enterprises in which he participated. Several fast-food franchises around town. A steam laundry. A Christmas tree farm. Hunting camps. Apartment buildings in the black sections of town. We even found a scrawled note listing income he had realized from arranging private adoptions over a period of twenty-five years.

In short, Leo Marston appeared to administer an empire of great and small dominions, all entirely aboveboard. On closer examination, however, a dark underside began to show itself. One of the boxes Leo had planned to burn contained records of a collection agency wholly owned by him. Listed as an officer of that company was one Raymond Aucoin Presley. This was the first tangible proof of a connection between Marston and Presley. We found copies of letters sent to hundreds of local citizens, demanding payment of debts on everything from materials bought through Marston companies to personal loans made by the judge. It wasn’t hard to guess what function Presley served when these letters failed to bring payment of the outstanding balances. Most important, he was operating in this capacity during 1968, while serving as a Natchez police officer and in the month Del Payton was murdered. Closer inspection of Marston’s other companies revealed that Presley was listed as a paid “security consultant” to several of them.

Another of the “burn boxes” contained records of land transfers made to Marston or his business partners. I noted the disturbing frequency with which the parcels of land had been sold by recent widows whose estates Marston’s firm had handled. Many other sellers could be cross-indexed to debtors listed in the “collection-agency” box. It was a letter from this box that gave me my first glimmer of a possible motive for Payton’s murder.

The letter pertained to a large parcel of land south of town, near the present industrial park. It was written in an oblique style, but from it I inferred that Marston had used a secret intermediary to buy this parcel of land. Thus, while Marston was not legally the owner, he controlled the parcel’s future use and would receive all monies from such use, without anyone but the intermediary knowing about it. A related letter—this one from one Zebulon Hickson, the owner of several carpet factories in Georgia and Alabama—expressed interest in purchasing this land for use as a site for a new factory. Hickson also expressed concern about labor conditions in Adams County. He was aware that Natchez had long been a “union” town, but what concerned him more was the “wave of racial unrest” sweeping through Southern factories. This was clearly a euphemism for “nigger trouble.” What made all this interesting was that the letters had changed hands in January 1968, a few months before Del Payton died. The situation was oddly similar to the present one, in which Leo Marston owns the land BASF needs to have adequate space for its projected facility.

On Saturday night, things began to turn our way. I had requested Marston’s telephone records, but with the trial only a week away, I had little hope of getting them. Technically, phone records can be had at the touch of a computer key, but the phone company is a hidebound bureaucracy, and in actuality it can take weeks to get them. I’d put in a call to a Bell South executive in Jackson, who promised to try to expedite the process, and apparently he did. A local Bell South technician arrived Saturday night with a manila envelope containing Marston’s phone records, logging all calls beginning the day before Caitlin’s “libelous” article ran.

I hurried to Caitlin’s office, and we pored over the printouts together. On the day the article ran, there was a call from Marston’s law office to a number in Washington D.C. at 1:45 p.m. Caitlin quickly confirmed this number as the main switchboard at the Hoover Building, headquarters of the FBI. The call lasted eighteen minutes. One hour later Marston’s office had received a call from D.C., this one from a different number, which turned out to be John Portman’s office in the Hoover Building. In all, six calls passed between Marston’s office and the Hoover Building that day, and several more had since. We could now prove that a link existed between Leo Marston and the director of the FBI, who had worked the Del Payton murder as a field agent in 1968, when Marston was district attorney. And while we could not know what was said during those calls, their timing indicated that they were almost certainly related to the Payton case.

Caitlin’s father faxed us a steady stream of information on both Marston and Portman. Marston’s Mississippi history was familiar to me, but his national political activities weren’t. He is not only a powerful force in the Mississippi Republican Party, but also has major influence in the national GOP. Like many Mississippians, Marston was a nominal Democrat for most of his life, voting Democratic in local elections and Republican in presidential races. But in the Reagan era he jumped ship and voted GOP straight down the line. A close friend and adviser of Senators John Stennis and “Big” Jim Eastland—Mississippi Democrats whose seniority gave them unparalleled power on Capital Hill for decades—Marston became a major supporter of Senator Trent Lott, who eventually rose to the position of Senate majority leader.

John Portman’s thumbnail biography fascinated me. Born to old money in Connecticut while his father “patrolled the coast” of Rhode Island for German U-boats in his yacht, Portman was raised in a cloistered world of governesses and squash courts. He attended Choate, then Yale, where he was tapped for Skull-and-Bones and graduated second in his class at Yale Law. He was the right age for Vietnam but did not serve (perhaps owing to a dearth of yacht units). And while the FBI seemed an odd choice for a blue-blooded lawyer, during the Reagan era these “street” credentials fueled Portman’s meteoric rise into the upper ranks of the Justice Department. His stellar legal career as a U.S. attorney and federal judge was crowned by the poetic symmetry of returning to the fields where he’d begun, no longer a foot soldier but a general, and the media ate this up. The Hanratty affair provided the only bump in the road to his confirmation as FBI director, and since nothing could be proved, that came to naught. Portman sailed through the hearings without further trouble, and he has ruled the Bureau without a public misstep ever since.

In short, John Portman appeared to be a Teflon-coated bureaucrat with no visible weaknesses. His evasion of Vietnam service might be fertile ground for tabloids, but that wouldn’t help my case any, and there was probably nothing to it anyway, or it would have exploded during his confirmation hearings. The more I learned about him, the more I became certain that the only way I would uncover his secrets would be if Dwight Stone decided to break his silence, or if Peter Lutjens succeeded in stealing Stone’s final report from the Payton file in the FBI archive.

As I waded through the mountains of paper, eyes blurring, pulse skipping from caffeine, the tragedies of the past few days began to weigh heavily upon me. I’d involved myself in the Del Payton case for essentially selfish reasons, and because of my actions my parents’ house had been destroyed, my daughter terrorized, and Ruby Flowers murdered. The sad irony was that I had returned to Natchez to help heal my daughter, yet she had not received my full attention for many days, and had not even seen me for the past two. Yet something drove me on. Despite the selfishness that had initiated my quest, I sensed a new yet familiar energy stirring inside me. As I pored over the yellowed documents and musty ledgers, doing the sort of work I had done as a young lawyer, the sterile hollowness and free-floating anxiety I had felt in the months after Sarah’s death began to fall away. I felt alive again. And I knew this: Annie would fare far better with a father who was fully engaged with the world than with one grasping at meaning while clinging to the past.

I was not laboring in a vacuum. I was surrounded by idealistic kids who had no doubt they were on the right side of a noble quest for justice. During the forty-hour marathon, rumors and snippets of information filtered into the Examiner building that opinions in Natchez were not as clear-cut or one-sided as I had imagined. Many whites interviewed about the Payton case stated on the record that if Del Payton’s killer could be found, he should pay the maximum price, no matter who he might be or how much time had passed. They regretted that the battle between myself and Marston had generated such bad publicity for the town, but justice, they said, had to be served. A consensus was building that the rest of the nation had to be shown that Mississippi was not afraid to confront its old demons, if and when they could be dragged into the light.

The rumored riot of a few nights ago never materialized. On Saturday afternoon local black leaders staged a silent march to commemorate Ruby’s death, and the hushed procession walked without incident from the bandstand on the bluff to the crossroads of St. Catherine Street and Liberty Road, where slaves had been auctioned before the Civil War. The symbolism of this destination was not lost on whites, but black restraint in the face of Ruby’s murder was seen as a positive signal of black faith in Natchez’s justice system.

The real whirlwind was taking place outside Mississippi. We stood in the eye of a media storm, quietly going about the business of justice while national figures raged and pontificated about our backwardness. I soon began to see this as a metaphor for the Payton case itself. Yes, Ray Presley was probably the man who planted the bomb that had killed Del Payton. And perhaps Leo Marston had ordered him to do it. But it was clear to me that they had not acted alone. J. Edgar Hoover had not sealed the Payton file because it could potentially embarrass the state of Mississippi. And John Portman was not threatening me or punishing Peter Lutjens because of the local implications of this case. Nor was the fearsomely equipped sniper who shot at me from the levee the type of hit man an angry Southern businessman like Leo Marston would typically hire. Still more disturbing, I had begun to recall Dwight Stone’s comment about the timing of Payton’s slaying. Del was killed five weeks after Martin Luther King and three weeks before Robert Kennedy. Could there possibly have been some connection between a black factory worker in Natchez, Mississippi, and the explosive national politics of 1968?

As I pondered this question, my motive, which had begun as a quest for revenge and evolved with Livy’s arrival into an exorcism of my past, began to change again. Like a stubborn coal lying dormant in the ashes, a desire for truth flickered awake in my brain. Fanned to life, this glowing ember dimmed the baser motives that had brought me thus far. Revenge against Leo Marston is a hollow and perhaps even self-destructive goal. For by destroying him, would I not also destroy the second chance I’ve been granted for a life with Livy? And what of my hunger for explanations from Livy? Is it her fault that I’ve carried confusion and bitterness inside me for twenty years like shrapnel from some undecided war, a war that a more mature man would have put behind him long ago?

Ten years before Livy disappeared from my life, Del Payton was brutally murdered. That’s what’s important. That’s what has brought death back to this quiet town, and put the lives of those I love in mortal danger. I have but one riddle to answer. Ike the Spike told me that from the beginning. Not who killed Del Payton, but why. Because the why of it is as alive today as it was in 1968, and therein lies the answer to all my other questions. The relief that accompanied this liberating insight put me into a dead sleep on the couch in Caitlin’s office late Saturday night.

When Sunday dawned, this was the sum of our knowledge: a potential land deal in 1968 that involved Marston and a Georgia industrialist concerned with “racial” labor problems in Natchez (a deal that, as far as we could determine, was never consummated); phone records, proving suspicious contact between Marston and John Portman; and proof that Ray Presley had worked as a “security consultant” for Marston at the time of the Payton murder and while employed by the police department. It was a good harvest for forty hours’ work, but with the trial only three days away, it wasn’t nearly enough. All the NAIL BOSS HOG T-shirts in the world wouldn’t put me one step closer to proving Marston’s complicity in the murder. And without that I would never unravel the tangled skein of lies, corruption, and official silence that made Del Payton’s unpunished murder such a travesty, and forced my native state to bear the sole guilt which by rights should have been shared with others.

I needed a witness.

A star witness.

I needed Peter Lutjens or Dwight Stone.

At eleven a.m. on Sunday, I was about to call Stone to set up a secure call when Caitlin stuck a cup of scalding coffee in my hand and told me to go home and get dressed for Ruby’s funeral, which was scheduled to begin in three hours.

THIRTY-ONE (#ulink_90e19926-fad0-53e6-b947-1f9191a73131)

There is no more moving religious spectacle than a black funeral. If you’ve been to one, you know. If you haven’t, you don’t. Grief and remembrance are not sacrificed to the false gods of propriety and decorum but released into the air like primal music, channeled through the congregation in a collective discharge of pain. Ruby’s funeral should be like that, but it isn’t. It’s a ritual struggling under the weight of a political circus.

The church itself is under siege when I arrive, Annie in the backseat with my parents, Kelly in front of me, the other Argus men in a second car behind us. Sited on a hill in a stand of oak and cedar trees, the one-room white structure stands at the center of an army of vehicles, including a half dozen television trucks parked in a cluster beside the small cemetery. Lines of parked cars stretched down both sides of the church drive to Kingston Road, the winding old two-lane blacktop leading to the southern part of the county, where the Cold Hole bubbles up from the swamp.

A black-suited deacon waves us away from the drive, but Kelly ignores him and accelerates up the chute created by the parked cars, stopping only when he reaches the church steps. Camera crews instantly surround the BMW.

An old white-haired black man appears on the steps and jabs a finger at the human feeding frenzy around us. A wave of young men in their Sunday best rolls into the reporters, pushing them bodily away from the car, assisted by the three Argus men who drove up behind us. The old man comes down the steps and opens the back door of our car.

“I’m so sorry about this, Dr. Cage. Afternoon, Mrs. Cage. I’m Reverend Nightingale. Y’all come inside. One of these young men will park your car for you.”

Annie climbs between the seats into my arms, and I hurry up the steps with her as the camera crews close around us. A cacophony of shouted questions fills the air, but all I can distinguish are names: Marston, Portman, Mackey, Mayor Warren … As soon as we clear the church door, I turn and see my mother and father fighting their way through. A deacon slams the door behind them, leaving Kelly outside to help defend the entrance.

Two hundred black faces are turned toward the rear of the church, staring at us. People are jammed into the pews and packed along the walls like cordwood. The building seems to have more flesh in it than air. Only the center aisle is clear. Reverend Nightingale takes my mother’s arm and leads her along it, through the silent staring faces. Dad and I follow, me carrying Annie in my arms. The rear pews hold a bright sea of color, oscillating waves of blue, orange, yellow, and green (but no red, never red) and like proud sails above the waves, the most stunning array of hats I have seen outside of a 1940s film. All the children are dressed in white, like angels in training. As I follow my mother, Ruby’s voice sounds in my mind: You never wear red to no funeral; red says the dead person was a fool. The nearer we get to the altar, the darker the dresses get, until finally all are black.

At the end of the aisle Reverend Nightingale pulls my mother to the left, and I see our destination: a special box of pews standing against the wall, protected by a wooden rail. Despite the throng in the church, this box is empty. It’s the Mothers’ Bench, seats reserved for “sisters” who have reached a certain age (eighty, I think) and accepted “mother” status. Today it has been reserved for us. As we take our seats behind the rail, I see an identical box against the other wall. The Deacons’ Bench. Behind its rail sits Ruby’s immediate family: her husband, Mose; her three sons (all tall men with gray in their beards); her daughter, Elizabeth, wiping her eyes with a handkerchief; a handful of grandchildren (all in their twenties) and two infants.

A single camera crew has been allowed inside the church to tape the ceremony. The logo on the camera reads WLBT, the call letters of the black-owned station in Jackson. As I pan across the crowd, I see several familiar faces. In the first row sits Shad Johnson, wearing a suit that cost enough to buy any ten suits behind him. A few feet down the same pew sits the Payton family: Althea, Georgia, Del Jr., and his children. Althea nods to me, her brown eyes full of sympathy. In the second row sits the Gates family, the most powerful force in black politics in Natchez for forty years, now upstaged by the urban prodigal from Chicago. Several pews beyond them sits Willie Pinder, the former police chief. Pinder winks as I catch his eye. And in the last pew, sitting restlessly in the aisle seat as though prepared to make a quick exit, sits a man who looks very much like Charles Evers. The former mayor of Fayette and brother of Medgar looks like a man who does not intend to be bothered by anyone.

Suddenly the back door opens and two white faces float through it, Caitlin Masters and one of her photographers, escorted by Deputy Ike Ransom in his uniform. Ike remains just inside the back door, like a sentry, while Caitlin and her photographer slip through the crowd at the back wall and stop beside the WLBT camera.

In the shuffling, sweating silence the organist begins to play, and the purple-robed choir rises to its feet, beginning a restrained rendition of “Jesus, Keep Me Near the Cross.” The rich vibrato of two dozen voices fills the building, making the church reverberate like the soundboard of a grand piano. The whole congregation knows the words, and they join in softly.

As the last chorus fades, Reverend Nightingale makes his way slowly down the aisle and ascends to the pulpit. He is a small man, with fine white hair and frail limbs, but his voice has the deep, resonant timbre of the best black preachers.

“Brothers and sisters. Mothers. Deacons and officers. Visitors and friends. We are gathered here today to mourn the passing of Sister Ruby Flowers.”

A collective Mm-hm ripples through the church, punctuated by a couple of soft Amens. Reverend Nightingale touches the rim of his spectacles and continues.

“Everyone in this room knows how loyally Sister Flowers supported this church. She was born in 1917, and came to Jesus when she was nine years old. Reverend Early was pastor then. He was a godly man, but sparing with his praise. Yet as a boy I often heard him speak of how lucky he was to have womenfolk like Sister Flowers in his flock.”

Yes, Lord, comes the reply. Yes, sir.

“In the last few days a lot of reporters been asking me what Sister Flowers was like. Do you know what I tell them?”