По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

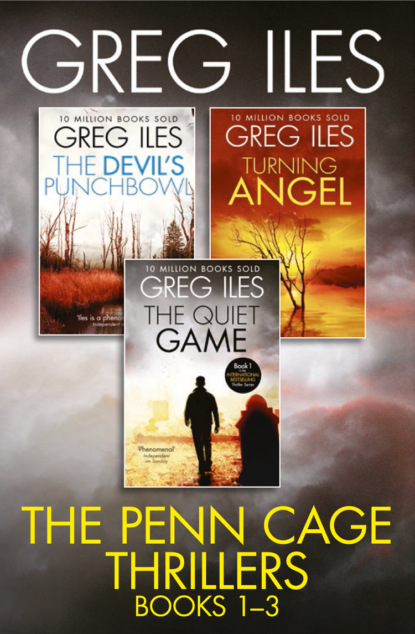

Greg Iles 3-Book Thriller Collection: The Quiet Game, Turning Angel, The Devil’s Punchbowl

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“There’s still Stone.”

“Don’t hold your breath. You want to come back to the paper and wade through some files? I’ll help.”

“Not yet. I’m going to take a drive. My parents and Annie are riding back with the Argus guys.”

Caitlin takes my hand. “Want some company?”

“Not this time.” I squeeze her hand. “But thanks for offering.”

She looks off toward Kingston Road. “You’re taking Kelly on this ride, right?”

“No.”

She looks back at me, her eyes worried, then suspicious. She drops my hand. “Tell Livy I said hello.”

“Livy? I have no intention of seeing Livy. Kelly can come if he wants, but in his own car. I just want to be alone for a while.”

Her eyes soften. “I’m sorry. I understand. I’ll tell him.” She rises on tiptoe and kisses me on the cheek. “Keep your eyes open.”

“I will.”

THIRTY-TWO (#ulink_16ccc79e-fd5a-5d5a-b977-7449cf6444ab)

Sometimes we think we are moving randomly. But random behavior is rare in humans. We are always spiraling around something, whether we see it or not, a secret center of gravity with the invisible power of a black hole. As a teenager, most of my “aimless” rides led me past Tuscany. Usually I would drive past the entrance, hoping to catch sight of Livy entering or leaving in her car. But a few times, at night, I would idle up the long driveway (it wasn’t gated then) and look up at her lighted window, staring at it like a caveman at a fire, then turn around and continue my endless orbit, a ritual that left me perpetually unsatisfied but which I was powerless to stop.

After Ruby’s funeral, I circumnavigate the county on its backroads, hurtling along gravel lanes with Kelly in my wake, driving his rented Taurus. Like a planet and its moon, we circle the town and the mystery that lies at the heart of it. Often the act of driving acts as a catalyst that allows the information banging around in my subconscious to order itself in a new way.

Today is different.

Today the emotional fallout from the funeral will not dissipate. Reverend Nightingale’s portrayal of my “unselfish” motives shamed me in a way I’ve never felt before. As he stood there praising me, I felt like a soldier who ran from battle being mistakenly awarded a Silver Star. At the other extreme was my anger at Shad Johnson, who hijacked Ruby’s funeral for his own political ends. And yet, if I were black, his suggestion that I retract my charges against Marston would make sense. My public statements may already have frightened liberal whites who might have voted for Shad into casting their ballots for Wiley Warren and the status quo.

After an hour of driving, the secret heart of my troubled orbit finally reveals itself. For the past week I’ve been acting like a writer. I was a prosecutor for twice as long as I’ve been a novelist, and I should have been thinking like one. At least my hands know where to take me, if my brain doesn’t. I’m on the Church Hill road, less than a mile from Ray Presley’s trailer. When I pull off beside the dilapidated structure, Kelly parks behind me, gets out, and jogs up to my window.

“What’s up, boss? Who lives here?”

“The man who killed Del Payton. I think he killed Ruby too.”

Kelly winces. “And what are we doing here?”

“What I should have done days ago.”

He squints and looks up the two-lane road. “I didn’t sign on to kill anybody. Or to watch it done.”

“I’m just going to talk to him.”

He gives me a skeptical look. “That sounds an awful lot like, ‘I’m just going to put it in a little way.’”

“I mean it. I’m here to talk. But this asshole is dangerous. I assume you won’t stand on ceremony if he tries to kill me.”

“He makes the first move, I got no problem punching his ticket.”

“Come on, then.”

I get out and walk toward the trailer, Kelly on my heels. We’re ten feet from the concrete steps when the front door bangs open and Presley yells from inside.

“That’s far enough! What the hell you doing here, Cage?”

“I want to talk to you.”

“Who’s that hippie?”

“A friend.”

“Is he carrying?”

“You bet your ass.”

A long pause. “I got nothing to say to you. Except you’re playing mighty fast and loose with your daddy’s future, all that shit you’re saying in the papers.”

“You haven’t heard my proposition, Ray. You might just save your life by listening. However much you’ve got left, anyway.”

“Yeah? Fuck you. You could save your daddy from going to jail by shutting the hell up and going back to Houston.”

“My father will never go to jail for the Mobile thing, Ray. But you will if you open your mouth.”

A bluejay cries raucously in the silence, the sound like a rusty gate closing.

“You got two minutes,” calls Presley. “But the hippie stays out there.”

I look back at Kelly, who walks casually past me and up to the open door, his hands held out to his sides. I can’t hear what he says, but when he’s done, he walks back to me and gives me the OK sign.

“What did you say to him?”

“I made sure he understood that hurting you would be a bad idea. He understands. Watch the girl in the corner, though. She looks shaky.”

Holding my hands in plain view, I walk up the three steps and into the trailer.

The stink of mildew and rotting food hits me in a wave, as though the trailer hasn’t been opened for days. As my eyes adjust to the dimness, I see Ray standing by his wall of police memorabilia. He’s dressed just as he was the other day: pajama pants, tank-top wife-beater T-shirt, and the John Deere cap pressed over his naked skull. He’s also holding a shotgun, which is aimed in my general direction, and wearing a shoulder holster with the butt of a large handgun protruding from it. Deeper in the gloom, on the couch by the IV caddy, sits the pallid blonde I saw on my first visit. Her legs are folded beneath her, and she’s clenching a rifle in her hands. She looks nervous enough to pull the trigger without provocation.

“So talk,” says Presley.

“I’ve got three days to prove Leo Marston conspired to kill Del Payton.”

He snorts. “Maybe you can find out who killed the Kennedys before Wednesday too.”

“I know you killed Del, Ray.”

Not even a tremor in the narrow face.