По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

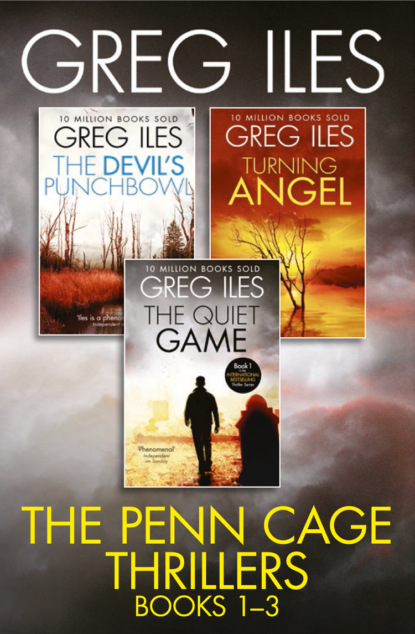

Greg Iles 3-Book Thriller Collection: The Quiet Game, Turning Angel, The Devil’s Punchbowl

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“So give me what I need to nail him.”

Ike shakes his head. “Gimme, gimme, gimme. I told you, it don’t play that way. I can point you in the right direction. But that’s it.”

“I don’t like playing games.”

Ransom snickers. “That’s what they do here, college boy. You ain’t been gone so long you forgot that yet. Right now they playing their favorite game of all.”

“What’s that?”

“The quiet game.”

“The quiet game?” Memories of Sarah flood into my brain, of her trying to trick Annie into being silent long enough for us to eat dinner in peace, by seeing who could go the longest without talking. “Who’s playing the quiet game, Ike?”

“Everybody, man. White and black both. Everybody keeping quiet, making like things is sweet and easy, trying to fish that new plant in here. Nobody wants nobody digging into Del’s killing. Nobody ’cept you. You got a reason.”

“What about you? What’s your reason?”

His grin vanishes as though it never existed. Hatred comes off him like steam. He extends his forefinger and taps his powerful chest with it. “That’s between me and me. Del’s killers is playing the quiet game too. They been playing it thirty years. Not even sweatin’. You got to make people nervous to win the quiet game. And I got a feeling you pretty good at that.”

Something is coiling within my chest, something I have not felt for years. It’s the hunter’s tension, wrapped like the armature of an electric motor, tight and copper-cored, charged with current and aching for resolution, for the frantic discharge of retribution.

“A lot of people think poking into this case would be damned dangerous,” I tell him.

Ike the Spike closes the distance between us and squeezes my right shoulder, his grip like the claw of a wild animal, like he could close his hand a little tighter and snap the bone.

“That’s where I come in. Boy, you lookin’ at dangerous. Ask anybody.”

We do not speak as Ransom drives back towards my parents’ house. I watch the dark streets drift by, lost in memory. I think mostly of the malpractice trial, of Marston’s savage cross-examination of my father just five weeks after his triple coronary bypass surgery. It required a supreme concentration of will on my part not to jump up in the courtroom and attack the man. In all my years as a prosecutor, I never stooped to the tactics Marston used that day.

“You got any FBI contacts?” Ike asks.

“A few. Why?”

“You might not want to use them on this.”

“Why not?”

“Free advice. Take it or leave it.”

“You know Ray Presley worked the Payton case, don’t you?”

Ike glances away from the road long enough to give me a warning look. “Presley was dirty from the day he was born. That motherfucker crazy as a wall-eyed bull and mean as a snake. You don’t talk to him unless I’m somewhere close.”

This does not bode well for my meeting tomorrow morning.

The radio chatters over a low background of static. There’s a domestic-violence call in the southern part of the county, followed by a disturbance at the gangplank of the riverboat casino. As we roll into my parents’ neighborhood, I glance over at Ransom. The man is too old to be doing the job he has.

“Can I ask you a question, Ike?”

He takes a Kool Menthol from his shirt pocket, lights up, and blows a stream of smoke at the windshield.

“How’d you wind up a cop?”

“That’s what college boys ask whores. How’d a girl like you end up here?”

“I remember the stories about you playing ball. Ike the Spike. You were a hero around here.”

He sniffs and takes another drag. “Like the man said, that was my fifteen minutes.”

“You must have played college ball.”

“Oh, yeah, I was the BNOC.”

“What’s that?”

“The Big Nigger On Campus.” His voice is laced with bitterness. “I got a full scholarship to Ohio State, but I went to Jackson State instead. First quarter of the first game, a guy took out my shoulder. Back then doctors couldn’t do shit for that.”

“You lost your scholarship?”

“They gave me my walking papers before I even caught my breath. I was good enough for the army, though. I’d been drafted in early sixty-six, but I had a college deferment. When I lost my scholarship, I couldn’t afford to stay in school. Next thing I knew, I was landing at Tan Son Nhut air base in DaNang.”

I am starting to perceive the twisted road that led Ike Ransom to this job. “I’d like to hear about it sometime.”

Another drag on the Kool. “You one of them war junkies?”

“No.”

“You get off on other people’s pain, though. That’s what writers do, ain’t it? Sell other people’s pain?”

“Some do, I guess.”

“Well, this is your big chance. There’s a heap of fucking pain at the bottom of this story.”

I try to gauge Ransom’s temper, but it’s impossible. “Sam says you’ve got a bad rep. Even with black people.”

He stubs out his cigarette and flips it out the window. “I was the third black cop on the Natchez P.D. Back then a lot of the force was Klan. I didn’t take that job to make no civil rights statement. I’d been an M.P. in Saigon, and that was the only thing I knew how to do. The first time I got called to a black juke, I had to go alone. When I walked in the door, everybody thought it was a big joke. Patting me on the back and laughing, handing me beer. But this big field nigger named Moon had a machete in there. He’d already cut the guy who was dicking his old lady, plus the first nigger who said something about it. He was sitting by hisself at a corner table. I’d seen lots of guys lose it overseas, and this guy was like that. Gone. I told him he had to give up the blade. He wouldn’t do it. When I held out my hand, he jumped up and charged me. I shot him through the throat.”

“Jesus.”

“I didn’t want to waste that brother. But I didn’t have no backup. And that pretty much set the tone for the next twenty years. I had the white department on one side, watching me like a hawk, making sure I was tough enough, and my people on the other, always fucking up, always begging for a break. I cut slack where I could, but goddamn, it seemed like they never learned. It got where I hated to pull a nigger over, knowing he’d be drunk or high. Hated to answer a domestic call. Couple of years of that, I was an outsider. It fucked with me, man. That’s what got me on the bottle.”

“Why didn’t you resign?”

Ransom rolls down his window, hawks and spits. “I didn’t come here to give you no Jerry Springer show.” He pulls something out of his shirt and hands it to me. It’s a card. On it are printed Ransom’s name and rank, and the phone numbers of the sheriff’s department. “My cell phone’s on the back. When you call, don’t use names. I’ll know you, and I’ll pick a place for a meet.”

“You’re the only person not named Payton who seems to want the truth told.”

The radio crackles again, this time about a theft of guns from a hunting camp in Anna’s Bottom. Ike picks up the transmitter and says he’ll respond to the call.