По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

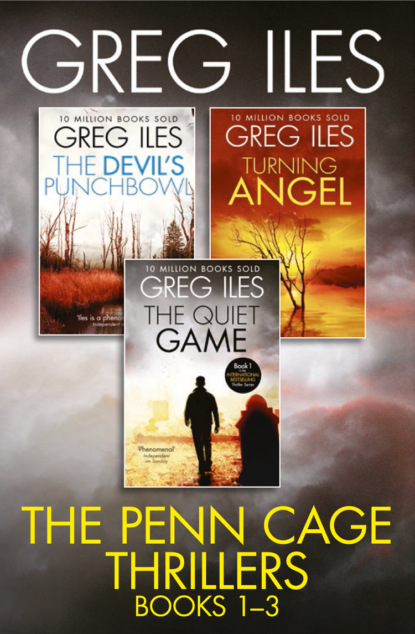

Greg Iles 3-Book Thriller Collection: The Quiet Game, Turning Angel, The Devil’s Punchbowl

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She shakes her head in confusion. “You can’t be serious.”

“I’m deadly serious. Althea. Don’t give it another thought.”

She wipes tears from her eyes, and I look away. The wall to her left holds the sacred trinity of photographs I’ve seen in the homes of many black families: Martin Luther King, JFK, and Abraham Lincoln. Sometimes you see Bobby, or FDR. But the Paytons have only the big three. A plastic clock hangs above the photographs, its face painted with a rather bloated likeness of Dr. King. The words I HAVE A DREAM appear in quotes beneath him.

“Georgia bought that clock from some traveling salesman in May of 1968,” Althea says. “It stopped running before that Christmas, but she never let me get rid of it.”

“Maybe it’s a collectors’ item.”

“I don’t care. Those clocks probably put a million dollars in some sharpie’s pocket.” She grips her knees with her palms and fixes her eyes on me. “Could I ask you one thing?”

“Why did I change my mind?”

“Yes.”

“I have a personal stake in the case now. I want to be honest with you about that.”

“Are you going to write a book about Del? Is that it?”

“No. But if anybody asks you what I was doing here, that’s what you tell them. And I mean anybody, police included. Okay?”

“Whatever you say. But what is your personal interest, if not a book?”

“I’d prefer to keep that to myself, Althea.”

She looks puzzled, then relieved. “I’m glad you’ve got a stake in it. You having a child like you do. It would be too hard if I thought you were taking this risk only for me.”

“I’m not. Rest assured of that.”

“Thank you.” She leans back in her chair and looks at me with apprehension. “What can you tell me? Have you learned anything yet?”

“We won’t be getting any help from the district attorney. The police either, if my guess is right. I’ve managed to obtain some documentary information dating back to 1968 that could be helpful, but that’s between us and God.”

“Can you tell me what it is?”

“No. I won’t expose you to potential criminal charges.”

She nods soberly. “Just tell me this. Do you think there’s any hope? Of finding out the truth, I mean.”

I fight the urge to be optimistic. A lawyer has to make that mistake only once to learn what it costs. You give people hope; then the pendulum swings the wrong way and they’re left shattered, as much by false hope as by misfortune.

“I wouldn’t take the case if there wasn’t hope. But I want to proceed cautiously. I promise to contact you if and when I learn anything of value. I understand that you’ve waited a long time for justice.”

Althea’s hands are clenched in her lap, the knuckles white.

“If you feel up to it, I’d like you to tell me what you can about what Del was doing at the battery plant before he died. For civil rights, I mean.”

She takes a deep breath and closes her eyes, as though striving to remember with perfect accuracy. “Del wasn’t any big civil rights worker. He was a workingman. He just saw things he thought were wrong and did what he could to change them. When he was a young man, he was carefree. You never saw a smile so full and happy. When he went to Korea, something changed in him. He still had that smile, but it didn’t fill up his eyes the way it used to. He was different inside. He got shot over there, and I think he saw some pretty bad things. When he got back, he told me life was too short to spend it standing at the back of the line.”

“When did he go to work at Triton Battery?”

“A couple of years after the war. He put in his time and saved his money back then. Said he didn’t want to marry me till he could afford to take care of me like I deserved.” Althea’s voice cracks a little, but she smiles. “I sure got tired of waiting. Del bought this house in 1959, for cash money. Not many black men could do that back then.”

“You got married in fifty-nine?”

She nods. “It was right around then that Del met Medgar.”

“Medgar Evers?”

“Yes. Medgar heard how good Del was doing at the plant, and wanted to meet him. Medgar was building up the NAACP back then, pushing voter registration. Del loved Medgar. Loved his quiet way. Said he’d known men like Medgar in the army. Quiet men who worked hard and wouldn’t back down for anything. Medgar took to Del too. He saw that Del didn’t hate the white man. Del believed if we could help white people see inside us, see past the color, their hearts would change.”

“So Medgar got Del into civil rights work?”

“Lord, yes. Medgar ate right in this house whenever he came through town.” Althea shakes her head sadly. “When Beckwith killed Medgar in June of sixty-three, Del changed again. He said the war had come home to America. Then President Kennedy was shot that November. Del had joined the NAACP by then, of course, and by 1965 he was in charge of voter registration for this area. Del was the highest-ranking black man at the battery plant. Even the white men liked him. They knew he knew his job.”

“Who do you think planted that bomb, Althea?”

“Well … the Klan, I guess. There were a lot of beatings out at the paper mill around then, Klan workers beating black workers. You know. Scaring them off. There was some Klan at the tire plant, and at the battery plant too.”

“A car bomb is quite an escalation from a beating. Did Del have any personal enemies you know of?”

“Del didn’t have an enemy in this world.”

He had at least one, I say silently. But it’s certainly possible that Payton was chosen at random, to send a warning to someone. “Did he seem any more worried than usual about going to work near the time of his death?”

She shakes her head. “We had some death threats, but we got those with every promotion Del had. He just kept on keeping on. He’d say, ‘Thea, we can’t let ’em get us down.’”

I remember the nightmarish weeks of the Hanratty trial, when death threats arrived almost daily. What courage it must have taken for Del Payton to get up every morning of his life and go to work with men he knew wanted him dead.

“He was depressed,” Althea adds. “Over Dr. King’s death. Martin was assassinated just five weeks before Del was killed. And Del was so saddened by that, because already he saw the Movement being taken over by advocates of violence. Men with bitterness in their hearts. Stokely Carmichael and the rest. Black racists, he called them.”

The more I learn about Del Payton, the more I feel that his murder was a terrible loss to the community in which I grew up. “Does anything else stand out?”

“No. The FBI asked me all this back when it happened, and I told them the same thing. One day Del went to work and just didn’t come home.”

I looked helplessly around the room. Del Payton has been dead for thirty years, but he is as alive here as a dead man can be. When Annie is a grown woman, will this large a piece of my heart still be reserved for Sarah?

“Do you remember the names of any of the FBI agents who talked to you?”

“I remember one, very well. Agent Stone. He was about Del’s age, and he’d served in Korea too. Agent Stone really tried to help me. But he was the only one. He had a younger man with him who never said much. He didn’t care nothing about us. Like all the rest.”

“Do you remember his name?”

“No. Just a stuck-up Yankee. Agent Stone came by the house before he left town the last time. He apologized for not having gotten justice for Del. He was a good man, and I got the feeling he knew there was some dirty work at the crossroads on Del’s case.”

“Did he say anything specific?”

“No. He just seemed like he wanted to say more than he could.”