По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

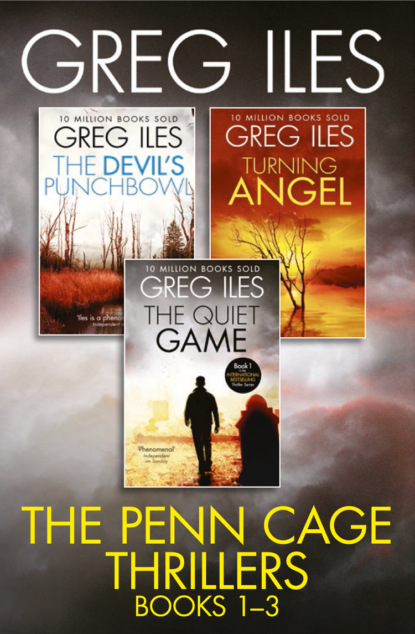

Greg Iles 3-Book Thriller Collection: The Quiet Game, Turning Angel, The Devil’s Punchbowl

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“What’s good? Hank Williams?”

“Hank’s all right, sure. But Jim Reeves, boy, that’s the prime stuff.”

I almost laugh. I’m no Jim Reeves fan, but whatever differences separate me from his redneck, he and I are bound together by manner, rites, and traditions imprinted deep beneath the skin. That’s why Caitlin’s newspaper story didn’t stop him from talking to me. I am white and Mississippi-born, and at bottom Jones perceives me as a member of his tribe. I wonder how wrong he is. If push comes to shove, and I’m forced to choose between white and black, will I realize there is no choice at all?

“Did the FBI question you?”

“Shit. Federal Bureau of Integration, we called ’em back then.” Now that we’re headed back, Jones has regained some of his old swagger. “Had ’em an office up in the City Bank building. A dozen Yankees with blue suits and ramrods up their butts. Agents came down from Jackson special just to question me. I think Bobby Kennedy sent ’em. Hoover wouldna sent assholes like these were.”

“They were tough on you?”

“A pack of pussies, more like. They didn’t do no better with the case than Creel and Temple did. And Kennedy got what he deserved a couple weeks later.”

Robert Kennedy deserved a bullet in the head? “What about an agent named Stone? Special Agent Dwight Stone?”

Jones’s face goes as dead as though someone zipped it shut. “Never heard of him.”

“He was lead agent on the Payton murder.”

The ex-Triton man sets his jaw and stares straight ahead like an obstinate mule. He remembers Agent Stone, all right. And not fondly.

We’re approaching the arched midpoint of the eastbound bridge. Above us, Natchez stretches across the horizon like a Cecil B. De Mille movie set, sweeping up from the cotton-rich bottomland to the spires and mansions on the great bluff, then back down again to the Triton plant and the sandbars where the river rolls on toward New Orleans and the Gulf. It’s the first time in years that I’ve seen the city from this aspect, and it’s breathtaking. Below us, two steamboats are docked at Under-the-Hill, grand anachronisms that now carry tourists rather than cotton merchants and gamblers. As we roll off the bridge and top the first long incline, the Pontiac sign appears in the distance. Jones’s posture instantly relaxes. This will be my last chance to speak to the man with any hope of a candid answer.

“What were you doing out there in the parking lot by yourself at eight o’clock that night?”

Something in his reaction telegraphs that he is about to lie. He does not squirm in his seat or make a sharp exclamation. Rather, a new stillness settles over him, one that sits heavily on a man unaccustomed to it.

“My wife called me,” he says. “She wanted me to get some bread and eggs and such. I was on night shift and the Pik Quick was about to close.”

This is the story recorded in the police report. But hearing Jones repeat it aloud, I sense the wrongness of it. “You were coming back from getting groceries when you saw the explosion?”

“I never got to leave.” He shifts in his seat, finally giving release to his nervous energy. “Had a problem with my battery. Or I thought it was my battery. Turned out to be my solenoid.”

A strange elation takes hold of me. Eight years of questioning hostile witnesses honed my intuition to a pretty fine point. Frank Jones is lying. He’s been lying for thirty years. And any cop worth a damn would have seen it as easily in 1968 as I saw it today. Dwight Stone would have seen it a damn sight quicker.

I pull onto the edge of the Pontiac lot and stop, then catch Jones’s left wrist and hold it tight. “Who else was in that parking lot that night?”

His eyes go wide with surprise. “What? Nobody.”

I squeeze harder. He tries to pull away, but he hasn’t the strength.

“Nobody, I tell you!”

“You saw the killer.”

“That’s a goddamn lie!”

“Then who was it? Who else was there that night?”

Jones jerks his arm free and rubs his wrist. “You don’t know shit!”

“I’m going to blow this case wide open, my friend. And the longer you lie, the harder it’s going to go on you.”

He glances nervously at the showroom window. He actually looks like he wants to talk, but he has stuck with a lie for thirty years, and he won’t abandon it easily now. He grabs the key from the ignition, killing the engine. “Get out of this goddamn car.”

I start to get out, then stop. “You don’t mind if I call your wife to confirm that story, do you? About her calling you to go get groceries?”

“Do what you want. I divorced that bitch thirty years ago. Just get the hell out of this ride.”

I climb out and walk to my father’s car. The other salesmen are lined up against the showroom window, staring openly now. As Jones switches seats and pulls the Trans-Am toward the building, I start the BMW and drive quickly off the lot.

One cell phone call to my mother tells me all I need to know. Frank Jones’s ex-wife still lives in Natchez. After a messy divorce she married the president of a local oil company, quite a trade up from Frank Jones. The “messiness” involved affairs Jones had trailed with several secretaries at the battery plant. I dial the oilman’s home and ask for the ex-wife by her new name: Little.

“This is Mrs. Little,” says a rather prim voice.

“Mrs. Little, this is Penn Cage.”

“Dr. Cage’s boy?”

“That’s right. I—”

“I remember when you used to take the blood and X rays at your daddy’s office.”

At least she didn’t hang up. “Yes, ma’am. I wanted to ask you a couple of questions, if you don’t mind.”

“What about?”

“The day Del Payton died.”

A hesitation. “What about it?”

“I just talked to your ex-husband, and—”

“Sweet Jesus. What did that no-count say about me?”

Her anger sounds fresh, even after thirty years. “He used you for an alibi, Mrs. Little. He said he went out to the Triton parking lot on the night Del Payton died because you asked him to pick up some groceries.”

“That’s a damn lie, pardon my French. He was in that parking lot because he was diddling one of his floozies.”

This remarkable statement stops me for a moment. “Are you … you’re saying you think someone was in the lot with him that night?”

“Are you hard of hearing? That no-good tomcat came home that night and asked me to tell the police the same story he told you. And I did, numbskull that I was.”

I’m not sure I’m breathing.

“The next morning I took the car to the grocery store—for real that time—and as I was loading the bags into the backseat, I found a pair of stockings. They weren’t mine, and they were not in pristine condition—if you know what I mean. When I got home, I kicked that sorry sack right out of the house. For good.”

“Have you ever told this to anyone before today?”