По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

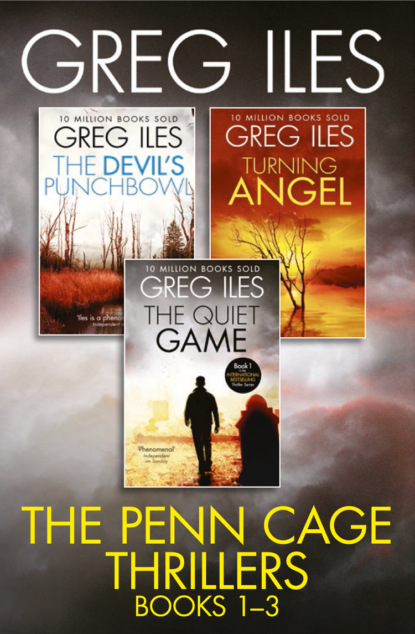

Greg Iles 3-Book Thriller Collection: The Quiet Game, Turning Angel, The Devil’s Punchbowl

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Jesus. Did this happen near the river? We heard some kind of call on the scanner, but it was coded.”

“That was it.”

“Can I print this story?”

“Absolutely. The more public this thing gets, the safer we are.”

“We ought to be very safe, then. I’m getting nonstop calls from the major papers, the networks, everybody.”

There’s a sharp knock at the door, and Caitlin walks into the hall for a hurried conference. When she returns, her face is flushed pink with excitement. “The police just trapped the Whitestone suspects in the Concord Apartments. I’m going over to cover the arrest.”

The Concord Apartments are a low-income housing development, and a center of drug and gang activity in Natchez. “The residents over there aren’t big fans of the police,” I warn her. “They’re probably as volatile as old dynamite right now.”

“That’s why I’m going. You want to come along?”

“I can’t take the time. I’ve got to file my interrogatories and requests for production along with my answer. That’ll keep Marston off balance, make him think I’m ready to go to court on a moment’s notice.”

“Speaking of Marston, where’s your other friend?”

“My other friend?”

She give me a sidelong glance. She means Livy.

“Oh. I have no idea. With her father, I guess.”

Caitlin obviously wants to say more, but she’s unwilling to do so in front of Kelly. “I’ve got to get going, guys.”

“Wait. Go with her, Kelly.”

Kelly looks at Caitlin, then back at me. “I think you’re the one who needs protection, boss.”

“I’ll have a photographer with me,” she protests. “I’ll be fine.”

“Kelly’s worth ten photographers. I’ll be here for at least two hours, then I’m going straight back to the motel. He can tell you how he saved my life on the way.”

Caitlin is wavering.

Kelly bends over, lifts a cuff of his jeans, and pulls out a small automatic, which he passes to me. “Safety’s on.”

I slip the gun into my pocket and look at Caitlin. “Satisfied?”

“Okay, I’ll take him. But you go straight to the motel from here. No side trips.”

“I need a computer. And coffee. Lots of coffee.”

“We’ve got plenty of both.”

Kelly and Caitlin still haven’t returned when I leave for the motel. While typing my discovery requests, I overheard enough newsroom conversation to follow the situation unfolding at the Concord Apartments. The two teenagers who allegedly shot Billy Earl Whitestone had holed up in the apartment of their grandmother. Somehow, Caitlin managed to get them on the telephone, and during that conversation one of the boys admitted to the shooting. He claimed he’d shot Whitestone because Ruby Flowers’s death had so upset his grandmother that he had to do something. He chose Whitestone as his victim because he’d often heard an uncle talk about how Whitestone had run the Klan during the “bad times.” An hour after this confession, the grandmother talked the boys into giving themselves up, on the condition that Caitlin be allowed to accompany them to the police station to ensure their safety. I assume Caitlin is still at the station now, running the police crazy and keeping Kelly jumping.

Kelly’s pistol is on my lap as I drive toward the motel. There’s no traffic on the streets, or even the highway. Fear has worked its way into the fabric of the town.

A police car screams out of the empty darkness, siren blaring, going in the opposite direction. Halfway to the motel, a jacked-up pickup filled with white teenagers roars alongside me, pauses as its occupants peer in at me, then roars off again. Night riders looking for a fight? Or kids trying to figure out what all the excitement’s about? I won’t know until I read tomorrow’s paper.

The single-story buildings of the Prentiss Motel remind me of the motor courts of my childhood vacations. But viewed without the kaleidoscopic lens of wonder, they are a mean and depressing sight. The thought of my parents forced to live here because of my actions is hard to bear. Yet they have not uttered one word of complaint since the fire, not even my mother, who urged me to avoid the Payton case from the beginning. Now that events have proved her right, what is she doing? Making the best of things. I feel like dragging some realtor out of bed and buying her the biggest goddamn house in the city.

Orienting myself by the greenish glow of the swimming pool, I park and start walking toward our rooms with Kelly’s gun held along my leg. Halfway there, I feel a sudden chill.

There’s someone sitting in one of the pool chairs. Fifty feet away, a dark silhouette against the wavering light of the water. As I walk down the long row of doors, the figure rises from the chair. I put my finger on the trigger of the pistol and quicken my steps.

“Penn?”

The voice stops me cold. It’s Livy.

I slip Kelly’s gun into my waistband and jog toward the pool fence. Livy opens the gate and waits just beyond it. She’s wearing a strapless white evening dress that looks strangely formal beside the deserted swimming pool. The moonlight falls lustrous upon her shoulders but is somehow lost in her eyes, which look more gray than blue tonight.

“What are you doing here? What’s the matter?”

“I wanted to see you,” she says. “That’s all. I had to see you.”

“Is everything all right?”

“That depends on what you mean by all right. Things are a bit tense at our house. More than a bit, really. But I’m sure your house was like that when my father went after yours.”

She has no idea how bad things got at our house during the year leading up to that trial. But soon she might. Before she can say anything else, I ask what I’ve been wanting to ask since I saw her at the airport in Baton Rouge.

“Livy, a few nights ago, at a party … your mother threw a drink in my face.”

“She what?”

“She told me I’d ruined your life.”

Livy’s expression does not change. She holds her eyes on mine, attentive as a spectator at the opera. But I sense that she’s expending tremendous effort to maintain this illusion of normalcy.

“What was she talking about?” I ask.

“I have no idea.” She looks away from me. “Mom probably doesn’t either. She’s a hairbreadth from the DTs by five o’clock every day. Daddy’s talking about sending her to Betty Ford.”

“She was referring to something specific. I saw her eyes.”

Livy turns and peers into the cloudy water. “My divorce has upset her quite a bit. Divorce isn’t part of the fairy tale. If it were, she’d have left my father long ago.”

“I thought you were only separated.”

“Pending divorce, then. It’s just semantics.” She looks at me over her bare shoulder, an injured look in her eyes. “You think I’d ask you to make love to me if there was a chance my husband and I would get back together?”

This is one of those moments where we make a heaven or hell of the future, by choosing honesty or deception. “I don’t know. You weren’t that discriminating in the past.”

She flinches, but she can endure much worse than this. “The past, the past,’ she says. “The damned sacred past. Can’t we try living in the present for once?”