По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

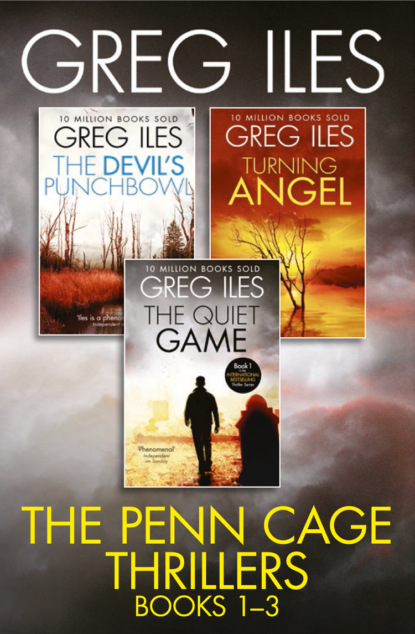

Greg Iles 3-Book Thriller Collection: The Quiet Game, Turning Angel, The Devil’s Punchbowl

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

FOUR (#ulink_0bc4a2ed-a13a-502a-b1a5-7ca24a4f4fd3)

All my life, whenever problems of great import required discussion—health, family, money, marriage—the library was the place it was done. Yet my positive feelings about the room far outweigh my anxieties. The ash-paneled library is so much a part of my father’s identity that he carries its scent wherever he goes—an aroma of fine wood, cigar smoke, aging leather, and whiskey. Born to working-class parents, he spent the first real money he made to build this room and fill it with books: Aristotle to Zoroaster and everything in between, with a special emphasis on the military campaigns of the Civil War. I feel more at home here than anywhere in the world. In this room I educated myself, discovered my gift for language, learned that the larger world lay not across oceans but within the human mind and heart. Years spent in this room made law school relatively simple and becoming a writer possible, even necessary.

Dad enters through a different door, carrying a bourbon-and-water brown enough to worry me. We each take one of the leather recliners, which are arranged in the classic bourgeois style: side by side facing the television. He clips the end of a Partagas, licks the end so that it won’t peel, and lights it with a wooden match. A cloud of blue smoke wafts toward the beamed ceiling.

“Dad, I—”

“Let me start,” he says, staring across the room at his biographies, most of them first editions. “Son, there comes a time in every man’s life when he realizes that the people who raised him from infancy now require the favor to be returned, whether they know it or not.” He stops to puff on the Partagas. “This is something you do not yet have to worry about.”

“Dad—”

“I am kindly telling you to mind your own business. You and Annie are welcome here for the next fifty years if you want to stay, but you’re not invited to pry into my private affairs.”

I lean back in the recliner and consider whether I can honor my father’s request. Given what my mother told me, I don’t think so. “What’s Ray Presley holding over you, Dad?”

“Your mother talks too much.”

“You know that’s not true. She thinks you’re in trouble. And I can help you. Tell me what Presley has on you.”

He picks up his drink and takes a long pull, closing his eyes against the anesthetic fire of the bourbon. “I won’t have this,” he says quietly.

I don’t want to ask the next question—I’d hoped never to raise the subject again—but I must. “Is it something like what you did for Sarah? Helping somebody at the end?”

He sighs like a man who has lived a thousand years. “That’s a rare situation. And when things reach that point, the family’s so desperate to have the horror and pain removed from the patient’s last hours that they look at you like an instrument of God.”

He drinks and stares at his books, lost in contemplation of something I cannot guess at. He has aged a lot in the eighteen years since I left home. His beard is no longer salt-and-pepper but silver white. His skin is pale and dotted by dermatitis, his joints eroded and swollen by psoriatic arthritis. He is sixteen years past his triple bypass (and counting) and he recently survived the implantation of two stents to keep his cardiac vessels open. All this—physical maladies more severe than those of most of his patients—he bears with the resignation of Job. The wound that aged him most, the one that has never quite healed, was a wound to the soul. And it came at the hands of another man.

When I was a freshman at Ole Miss, my father was sued for malpractice. The plaintiff had no case; his father had died unexpectedly while under the care of my father and five specialists. It was one of those inexplicable deaths that proved for the billionth time that medicine is an inexact science. Dad was as stunned as the rest of the medical community when “Judge” Leo Marston, the most prominent lawyer in town and a former state attorney general, took the man’s case and pressed it to the limit. But no one was more shocked than I. Leo Marston was the father of a girl I had loved in high school, and whom I still think about more than is good for me. Why he should viciously attack my father was beyond my understanding, but attack he did. In a marathon of legal maneuvering that dragged on for fourteen months, Marston hounded my father through the legal system with a vengeance that appalled the town. In the end Dad was unanimously exonerated by a jury, but by then the damage had been done.

For a physician of the old school, medical practice is not a profession or even an art, but the abiding passion of existence. A brilliant boy is born to poor parents during the Depression. From childhood he works to put food on the table. He witnesses privation and sickness not at a remove, but face to face. He earns a scholarship to college but must work additional jobs to cover his expenses. He contracts with the army to pay for his medical education in exchange for years of military service. After completing medical school with an exemplary record, he does not ask himself the question every medical student today asks himself: what do I wish to specialize in? He is ready to go to work. To begin treating patients. To begin living.

For twenty years he practices medicine as though his patients are members of his family. He makes small mistakes; he is human. But in twenty years of practice not one complaint is made to the state medical board, or any legal claim made against him. He is loved by his community, and that love is his life’s bread. To be accused of criminal negligence in the death of a patient stuns him, like a war hero being charged with cowardice. Rumor runs through the community like a plague, and truth is the first casualty. His confidence in the rightness of his actions is absolute, but after months of endlessly repeated allegations, doubt begins to assail him. A lifetime of good works seems to weigh as nothing compared to one unsubstantiated charge. Smiles on the street appear forced to him, the greetings of neighbors cool. Stress works steadily and ruthlessly upon him, finally culminating in a myocardial infarction, which he barely survives.

Six weeks later the trial begins, and it’s like stepping into the eye of a hurricane. Control rests in the hands of lawyers, men with murky motives and despicable tactics. Expert witnesses second-guess every medical decision. He sits alone in the witness box, condemned before family, friends, and community, cross-examined as though he were a child murderer. When the jury finds in his favor, he feels no joy. He feels like a man who has just lost both legs being told he is lucky to be alive.

Could the present-day blackmail somehow be tied to that calamitous case? I have never understood the reason for Leo Marston’s attack, and I’ve always felt that my father—against his nature—must have been keeping the truth from me. My mother believes Ray Presley is behind the blackmail, and I recall that Judge Marston often hired Presley to do “security work” when I was in high school. This translated into acting as unofficial baby-sitter for Marston’s teenage daughter, Olivia, who was also my lover. I remember nights when Presley’s truck would swing by whatever hangout the kids happened to be frequenting, its hatchet-faced driver glaring from the window, making sure Livy didn’t get into any serious trouble. One night Presley actually pulled up behind my car in the woods and rapped on the fogged windows, terrifying Livy and me. I still remember his face peering into the clear circle I rubbed on the window to look out, his eyes bright and ferretlike, searching the backseat for a sight of Livy unclothed. The hunger in those eyes …

“Does this have anything to do with Leo Marston?” I ask softly.

Dad flinches from his reverie. Even now the judge’s name has the power to harm. “Marston?” he echoes, still staring at his books. “What makes you say that?”

“It’s one of the only things I’ve never understood about your life. Why Marston went after you.”

He shakes his head. “I’ve never known why he did it. I’d done nothing wrong. Any physician could see that. The jury saw it too, thank God.”

“You’ve never heard anything since? About why he took the case or pressed it so hard?”

“To tell you the truth, son, I always had the feeling it had something to do with you. You and Olivia.”

He turns to me, his eyes not accusatory but plainly questioning. I am too shocked to speak for a moment. “That … that’s impossible,” I stammer. “I mean, nothing really bad ever happened between Livy and me. It was the trial that drove the last nail into our relationship.”

“Maybe that was Marston’s goal all along. To drive you two apart.”

This thought occurred to me nineteen years ago, but I discounted it. Livy abandoned me long before her father took on that malpractice case.

Dad shrugs as if it were all meaningless now. “Who knows why people do anything?”

“I’m going to go see Presley,” I tell him. “If that’s what I have to do to—”

“You stay away from that son of a bitch! Any problems I have, I’ll deal with my own way.” He downs the remainder of his bourbon. “One way or another.”

“What does that mean?”

His eyes are blurry with fatigue and alcohol, yet somehow sly beneath all that. “Don’t worry about it.”

I am suddenly afraid that my father is contemplating suicide. His death would nullify any leverage Presley has over him and also provide my mother with a generous life insurance settlement. To a desperate man, this might well seem like an elegant solution. “Dad—”

“Go to bed, son. Take care of your little girl. That’s what being a father’s all about. Sparing your kids what hell you can for as long as you can. And Annie’s already endured her share.”

We turn to the door at the same moment, each sensing a new presence in the room. A tiny shadow stands there. Annie. She seems conjured into existence by the mention of her name.

“I woke up by myself,” she says, her voice tiny and fearful. “Why did you leave, Daddy?”

I go to the door and sweep her into my arms. She feels so light sometimes that it frightens me. Hollow-boned, like a bird. “I needed to talk to Papa, punkin. Everything’s fine.”

“Hello, sweet pea,” Dad says from his chair. “You make Daddy take you to bed.”

I linger in the doorway, hoping somehow to draw out a confidence, but he gives me nothing. I leave the library with Annie in my arms, knowing I will not sleep, but knowing also that until my father opens up to me, there is little I can do to help him.

FIVE (#ulink_9640b1ba-c0a7-5369-bf75-32c851cc5317)

My father’s prediction about media attention proves prescient. Within forty-eight hours of my arrival, calls about interviews join the ceaseless ringing of patients calling my father. My mother has taken messages from the local newspaper publisher, radio talk-show hosts, even a TV station in Jackson, the state capital, two hours away. I decide to grant an interview to Caitlin Masters, the publisher of the Natchez Examiner, on two conditions: that she not ask questions about Arthur Lee Hanratty’s execution, and that she print that I will be vacationing in New Orleans until after the execution has taken place. Leaving Annie with my mother—which delights them both—I drive Mom’s Nissan downtown in search of Biscuits and Blues, a new restaurant owned by a friend of mine but which I have never seen.

It was once said of American cities that you could judge their character by their tallest buildings: were they offices or churches? At a mere seven stories, the Eola Hotel is the tallest commercial structure in Natchez. Its verdigris-encrusted roof peaks well below the graceful, copper-clad spire of St. Mary Minor Basilica. Natchez’s “skyline” barely rises out of a green canopy of oak leaves: the silver dome of the synagogue, the steeple of the Presbyterian church, the roofs of antebellum mansions and stately public buildings. Below the canopy, a soft and filtered sunlight gives the sense of an enormous glassed-in garden.

Biscuits and Blues is a three-story building on Main, with a large second-floor balcony overlooking the street. A young woman stands talking on a cell phone just inside the door—where Caitlin Masters promised to meet me—but I don’t think she’s the newspaper publisher. She looks more like a French tourist. She’s wearing a tailored black suit, cream silk blouse, and black sandals, and she is clearly on the sunny side of thirty. But as I check my watch, she turns face on to me and I spot a hardcover copy of False Witness cradled in her left arm. I also see that she’s wearing nothing under the blouse, which is distractingly sheer. She smiles and signals that she’ll be off the phone in a second, her eyes flashing with quick intelligence.

I acknowledge her wave and wait beside the door. I’m accustomed to young executives in book publishing, but I expected something a little more conventional in the newspaper business, especially in the South. Caitlin Masters stands with her head cocked slightly, her eyes focused in the middle distance, the edge of her lower lip pinned by a pointed canine. Her skin is as white as bone china and without blemish, shockingly white against her hair, which is black as her silk suit and lies against her neck like a gleaming veil. Her face is a study in planes and angles: high cheekbones, strong jawline, arched brows, and a straight nose, all uniting with almost architectural precision, yet somehow escaping hardness. She wears no makeup that I can see, but her green eyes provide all the accent she needs. They seem incongruous in a face that almost cries out for blue ones, making her striking and memorable rather than merely beautiful.

As she ends her call, she speaks three or four consecutive sentences, and a strange chill runs through me. Ivy League Boston alloyed with something softer, a Brahmin who spent her summers far away. On the telephone this morning I didn’t catch it, but coupled with her face, that voice transforms my suspicion to certainty. Caitlin Masters is the woman I spoke to on the flight to Baton Rouge. Kate … Caitlin.

She holds out her hand to shake mine, and I step back. “You’re the woman from the plane. Kate.”

Her smile disappears, replaced by embarrassment. “I’m surprised you recognize me, dressed like I was that day.”

“You lied to me. You told me you were a lawyer. Was that some kind of setup or what?”

“I didn’t tell you I was a lawyer. You assumed I was. I told you I was a First Amendment specialist, and I am.”