По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

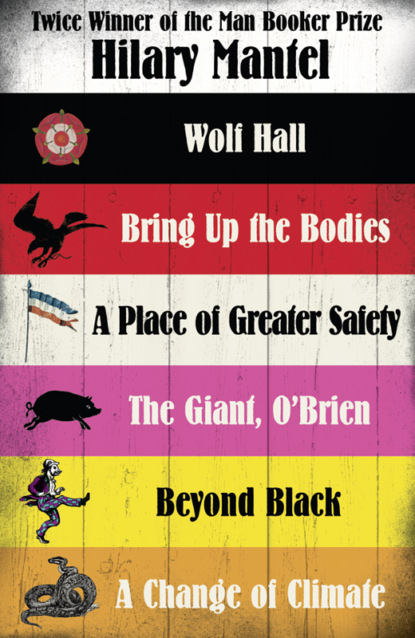

Hilary Mantel Collection: Six of Her Best Novels

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Perhaps I invent them.’

‘Oh, I don't think so.’ Cavendish is shocked. ‘You couldn't do that for long.’

‘It is a method of remembering. I learned it in Italy.’

‘There are people, in this household and elsewhere, who would give much to know the whole of what you learned in Italy.’

He nods. Of course they would. ‘But now, where were we? Harry Percy, who is as good as married, you say, to Lady Anne Boleyn, is standing before his father, and the father says …?’

‘That if he comes into the title, he would be the death of his noble house – he would be the last earl of Northumberland there ever was. And “Praise be to God,” he says, “I have more choice of boys …” And he stamped off. And the boy was left crying. He had his heart set on Lady Anne. But the cardinal married him to Mary Talbot, and now they're as miserable as dawn on Ash Wednesday. And the Lady Anne said – well, we all laughed at the time – she said that if she could work my lord cardinal any displeasure, she would do it. Can you think how we laughed? Some sallow chit, forgive me, a knight's daughter, to menace my lord cardinal! Her nose out of joint because she could not have an earl! But we could not know how she would rise and rise.’

He smiles.

‘So tell me,’ Cavendish says, ‘what did we do wrong? I'll tell you. All along, we were misled, the cardinal, young Harry Percy, his father, you, me – because when the king said, Mistress Anne is not to marry into Northumberland, I think, I think, the king had his eye cast on her, all that long time ago.’

‘While he was close with Mary, he was thinking about sister Anne?’

‘Yes, yes!’

‘I wonder,’ he says, ‘how it can be that, though all these people think they know the king's pleasure, the king finds himself at every turn impeded.’ At every turn, thwarted: maddened and baffled. The Lady Anne, whom he has chosen to amuse him, while the old wife is cast off and the new wife brought in, refuses to accommodate him at all. How can she refuse? Nobody knows.

Cavendish looks downcast because they have not continued the play. ‘You must be tired,’ he says.

‘No, I'm just thinking. How has my lord cardinal …’ Missed a trick, he wants to say. But that is not a respectful way to speak of a cardinal. He looks up. ‘Go on. What happened next?’

In May 1527, feeling embattled and bad-tempered, the cardinal opens a court of inquiry at York Place, to look into the validity of the king's marriage. It's a secret court; the queen is not required to appear, or even be represented; she's not even supposed to know, but all Europe knows. It is Henry who is ordered to appear, and produce the dispensation that allowed him to marry his brother's widow. He does so, and he is confident that the court will find the document defective in some way. Wolsey is prepared to say that the marriage is open to doubt. But he does not know, he tells Henry, what the legatine court can do for him, beyond this preparatory step; since Katherine, surely, is bound to appeal to Rome.

Six times (to the world's knowledge) Katherine and the king have lived in hope of an heir. ‘I remember the winter child,’ Wolsey says. ‘I suppose, Thomas, you would not be back in England then. The queen was taken unexpectedly with pains and the prince was born early, just at the turn of the year. When he was less than an hour old I held him in my arms, the sleet falling outside the windows, the chamber alive with firelight, the dark coming down by three o'clock, and the tracks of birds and beasts covered that night by the snow, every mark of the old world wiped out, and all our pain abolished. We called him the New Year's prince. We said he would be the richest, the most beautiful, the most devoted. The whole of London was lit up in celebration … He breathed fifty-two days, and I counted every one of them. I think that if he had lived, our king might have been – I do not say a better king, for that could hardly be – but a more contented Christian.’

The next child was a boy who died within an hour. In the year 1516 a daughter was born, the Princess Mary, small but vigorous. The year following, the queen miscarried a male child. Another small princess lived only a few days; her name would have been Elizabeth, after the king's own mother.

Sometimes, says the cardinal, the king speaks of his mother, Elizabeth Plantagenet, and tears stand in his eyes. She was, you know, a lady of great beauty and calm, so meek under the misfortunes God sent her. She and the old king were blessed with many children, and some of them died. But, says the king, my brother Arthur was born to my mother and father within a year of their marriage, and followed, in not too long a time, by another goodly son, which was me. So why have I been left, after twenty years, with one frail daughter whom any vagrant wind may destroy?

By now they are, this long-married couple, dragged down by the bewildered consciousness of sin. Perhaps, some people say, it would be a kindness to set them free? ‘I doubt Katherine will think so,’ the cardinal says. ‘If the queen has a sin laid on her conscience, believe me, she will shrive it. If it takes the next twenty years.’

What have I done? Henry demands of the cardinal. What have I done, what has she done, what have we done together? There is no answer the cardinal can make, even though his heart bleeds for his most benevolent prince; there is no answer he can make, and he detects something not entirely sincere in the question; he thinks, though he will not say so, except in a small room alone with his man of business, that no rational man could worship a God so simply vengeful, and he believes the king is a rational man. ‘Look at the examples before us,’ he says. ‘Dean Colet, that great scholar. Now he was one of twenty-two children, and the only one to live past infancy. Some would suggest that to invite such attrition from above, Sir Henry Colet and his wife must have been monsters of iniquity, infamous through Christendom. But in fact, Sir Henry was Lord Mayor of London –’

‘Twice.’

‘– and made a very large fortune, so in no way was he slighted by the Almighty, I would say; but rather received every mark of divine favour.’

It's not the hand of God kills our children. It's disease and hunger and war, rat-bites and bad air and the miasma from plague pits; it's bad harvests like the harvest this year and last year; it's careless nurses. He says to Wolsey, ‘What age is the queen now?’

‘She will be forty-two, I suppose.’

‘And the king says she can have no more children? My mother was fifty-two when I was born.’

The cardinal stares at him. ‘Are you sure?’ he says: and then he laughs, a merry, easy laugh that makes you think, it's good to be a prince of the church.

‘Well, about that, anyway. Over fifty.’ They were hazy about these things in the Cromwell family.

‘And did she survive the ordeal? She did? I congratulate both of you. But don't tell people, will you?’

The living result of the queen's labours is the diminutive Mary – not really a whole princess, perhaps two-thirds of one. He has seen her when he has been at court with the cardinal, and thought she was about the size of his daughter Anne, who is two or three years younger.

Anne Cromwell is a tough little girl. She could eat a princess for breakfast. Like St Paul's God, she is no respecter of persons, and her eyes, small and steady as her father's, fall coldly on those who cross her; the family joke is, what London will be like when our Anne becomes Lord Mayor. Mary Tudor is a pale, clever doll with fox-coloured hair, who speaks with more gravity than the average bishop. She was barely ten years old when her father sent her to Ludlow to hold court as Princess of Wales. It was where Katherine had been taken as a bride; where her husband Arthur died; where she herself almost died in that year's epidemic, and lay bereft, weakened and forgotten, till the old king's wife paid out of her private purse to have her brought back to London, day by painful day, in a litter. Katherine had hidden – she hides so much – any grief at the parting with her daughter. She herself is daughter of a reigning queen. Why should Mary not rule England? She had taken it as a sign that the king was content.

But now she knows different.

As soon as the secret hearing is convened, Katherine's stored-up grievances come pouring out. According to her, the whole business is the fault of the cardinal. ‘I told you,’ Wolsey said. ‘I told you it would be. Look for the hand of the king in it? Look for the will of the king? No, she cannot do that. For the king, in her eyes, is immaculate.’

Ever since Wolsey rose in the king's service, the queen claims, he has been working to push her out of her rightful place as Henry's confidante and adviser. He has used every means he can, she says, to drive me from the king's side, so that I know nothing of his projects, and so that he, the cardinal, should have the direction of all. He has prevented my meetings with the ambassador of Spain. He has put spies in my household – my women are all spies for him.

The cardinal says, wearily, I have never favoured the French, nor the Emperor neither: I have favoured peace. I have not stopped her seeing the Spanish ambassador, only made the quite reasonable request that she should not see him alone, so that I might have some check on what insinuations and lies he presents to her. The ladies of her household are English gentlewomen who have a right to wait upon their queen; after almost thirty years in England, would she have nothing but Spaniards? As for driving her from the king's side, how could I do that? For years his conversation was, ‘The queen must see this,’ and ‘Katherine will like to hear of this, we must go to her straight away.’ There never was a lady who knew better her husband's needs.

She knows them; for the first time, she doesn't want to comply with them.

Is a woman bound to wifely obedience, when the result will be to turn her out of the estate of wife? He, Cromwell, admires Katherine: he likes to see her moving about the royal palaces, as wide as she is high, stitched into gowns so bristling with gemstones that they look as if they are designed less for beauty than to withstand blows from a sword. Her auburn hair is faded and streaked with grey, tucked back under her gable hood like the modest wings of a city sparrow. Under her gowns she wears the habit of a Franciscan nun. Try always, Wolsey says, to find out what people wear under their clothes. At an earlier stage in life this would have surprised him; he had thought that under their clothes people wore their skin.

There are many precedents, the cardinal says, that can help the king in his current concerns. King Louis XII was allowed to set aside his first wife. Nearer home, his own sister Margaret, who had first married the King of Scotland, divorced her second husband and remarried. And the king's great friend Charles Brandon, who is now married to his youngest sister Mary, had an earlier alliance put aside in circumstances that hardly bear inquiry.

But set against that, the fact that the church is not in the business of breaking up established marriages or bastardising children. If the dispensation was technically defective, or in any other way defective, why can it not be mended with a new one? So Pope Clement may think, Wolsey says.

When he says this, the king shouts. He can shrug that off, the shouting; one grows accustomed, and he watches how the cardinal behaves, as the storm breaks over his head; half-smiling, civil, regretful, he waits for the calm that succeeds it. But Wolsey is becoming uneasy, waiting for Boleyn's daughter – not the easy armful, but the younger girl, the flat-chested one – to drop her coy negotiations and please the king. If she would do this, the king would take an easier view of life and talk less about his conscience; after all, how could he, in the middle of an amour? But some people suggest that she is bargaining with the king; some say that she wants to be the new wife; which is laughable, Wolsey says, but then the king is infatuated, so perhaps he doesn't demur, not to her face. He has drawn the cardinal's attention to the emerald ring Lady Anne now wears, and has told him the provenance and the price. The cardinal looked shocked.

After the Harry Percy debacle, the cardinal had got Anne sent down to her family house at Hever, but she had insinuated herself back to court somehow, among the queen's ladies, and now he never knows where she'll be, and whether Henry will disappear from his grasp because he's chasing her across country. He thinks of calling in her father, Sir Thomas, and telling him off again, but – even without mentioning the old rumour about Henry and Lady Boleyn – how can you explain to a man that as his first daughter was a whore, so his second one should be too: insinuating that it's some sort of family business he puts them into?

‘Boleyn is not rich,’ he says. ‘I'd get him in. Cost it out for him. The credit side. The debit side.’

‘Ah yes,’ the cardinal says, ‘but you are the master of practical solutions, whereas I, as a churchman, have to be careful not actively to recommend that my monarch embark on a studied course of adultery.’ He moves the quills around on his desk, shuffles some papers. ‘Thomas, if you are ever … How shall I put it?’

He cannot imagine what the cardinal might say next.

‘If you are ever close to the king, if you should find, perhaps after I am gone …’ It's not easy to speak of non-existence, even if you've already commissioned your tomb. Wolsey cannot imagine a world without Wolsey. ‘Ah well. You know I would prefer you to his service, and never hold you back, but the difficulty is …’

Putney, he means. It is the stark fact. And since he's not a churchman, there are no ecclesiastical titles to soften it, as they have softened the stark fact of Ipswich.

‘I wonder,’ Wolsey says, ‘would you have patience with our sovereign lord? When it is midnight and he is up drinking and giggling with Brandon, or singing, and the day's papers not yet signed, and when you press him he says, I'm for my bed now, we're hunting tomorrow … If your chance comes to serve, you will have to take him as he is, a pleasure-loving prince. And he will have to take you as you are, which is rather like one of those square-shaped fighting dogs that low men tow about on ropes. Not that you are without a fitful charm, Tom.’

The idea that he or anyone else might come to have Wolsey's hold over the king is about as likely as Anne Cromwell becoming Lord Mayor. But he doesn't altogether discount it. One has heard of Jeanne d'Arc; and it doesn't have to end in flames.

He goes home and tells Liz about the fighting dogs. She also thinks it strikingly apt. He doesn't tell her about the fitful charm, in case it's something only the cardinal can see.

The court of inquiry is just about to break up, leaving the matter for further advisement, when the news comes from Rome that the Emperor's Spanish and German troops, who have not been paid for months, have run wild through the Holy City paying themselves, plundering the treasuries and stoning the artworks. Dressed satirically in stolen vestments, they have raped the wives and virgins of Rome. They have tumbled to the ground statues and nuns, and smashed their heads on the pavements. A common soldier has stolen the head of the lance that opened the side of Christ, and has attached it to the shaft of his own murderous weapon. His comrades have torn up antique tombs and tipped out the human dust, to blow away in the wind. The Tiber brims with fresh bodies, the stabbed and the strangled bobbing against the shore. The most grievous news is that the Pope is taken prisoner. As the young Emperor, Charles, is nominally in charge of these troops, and presumably will assert his authority and take advantage of the situation, King Henry's matrimonial cause is set back. Charles is the nephew of Queen Katherine, and while he is in the Emperor's hands, Pope Clement is not likely to look favourably on any appeals passed up from the legate in England.

Thomas More says that the imperial troops, for their enjoyment, are roasting live babies on spits. Oh, he would! says Thomas Cromwell. Listen, soldiers don't do that. They're too busy carrying away everything they can turn into ready money.

Under his clothes, it is well known, More wears a jerkin of horsehair. He beats himself with a small scourge, of the type used by some religious orders. What lodges in his mind, Thomas Cromwell's, is that somebody makes these instruments of daily torture. Someone combs the horsehair into coarse tufts, knots them and chops the blunt ends, knowing that their purpose is to snap off under the skin and irritate it into weeping sores. Is it monks who make them, knotting and snipping in a fury of righteousness, chuckling at the thought of the pain they will cause to persons unknown? Are simple villagers paid – how, by the dozen? – for making flails with waxed knots? Does it keep farm workers busy during the slow winter months? When the money for their honest labour is put into their hands, do the makers think of the hands that will pick up the product?