По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

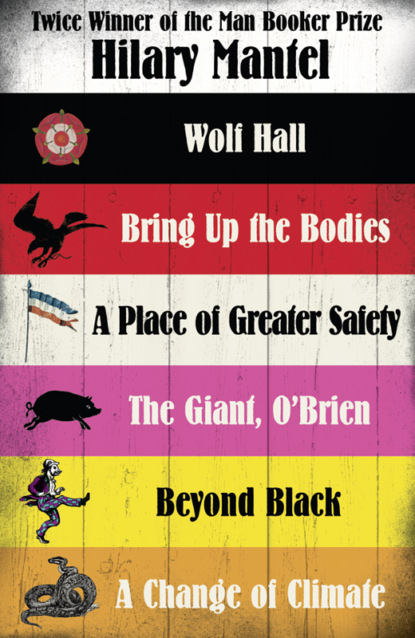

Hilary Mantel Collection: Six of Her Best Novels

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

We don't have to invite pain in, he thinks. It's waiting for us: sooner rather than later. Ask the virgins of Rome.

He thinks, also, that people ought to be found better jobs.

Let us, says the cardinal at this point, take a step back from the situation. He suffers some genuine alarm; it has always been clear to him that one of the secrets of stability in Europe is to have the papacy independent, and in the clutches of neither France nor the Emperor. But his nimble mind is already skipping towards some advantage for Henry.

Suppose, he says – for in this emergency, it will be to me that Pope Clement looks to hold Christendom together – suppose I were to cross the Channel, stop off in Calais to reassure our people there and suppress any unhelpful rumours, then travel into France and conduct face-to-face talks with their king, then progress to Avignon, where they know how to host a papal court, and where the butchers and the bakers, the candlestick-makers and the keepers of lodgings and indeed the whores have lived in hope these many years. I would invite the cardinals to meet me, and set up a council, so that the business of church government could be carried on while His Holiness is suffering the Emperor's hospitality. If the business brought before this council were to include the king's private matter, would we be justified in keeping so Christian a monarch waiting on the resolution of military events in Italy? Might we not rule? It ought not to be beyond the wit of men or angels to send a message to Pope Clement, even in captivity, and the same men or angels will bring a message back – surely endorsing our ruling, for we will have heard the full facts. And when, of course, in due time – and how we all look for that day – Pope Clement is restored to perfect liberty, he will be so grateful for the good order kept in his absence that any little matter of signatures or seals will be a formality. Voilà – the King of England will be a bachelor.

Before this can happen the king has to talk to Katherine; he can't always be hunting somewhere else, while she waits for him, patient, implacable, his place set for supper in her private apartments. It is June, 1527; well barbered and curled, tall and still trim from certain angles, and wearing white silk, the king makes his way to his wife's apartments. He moves in a perfumed cloud made of the essence of roses: as if he owns all the roses, owns all the summer nights.

His voice is low, gentle, persuasive, and full of regret. If he were free, he says, if there were no impediment, it is she, above all women, that he would choose for his wife. The lack of sons wouldn't matter; God's will be done. He would like nothing better than to marry her all over again; lawfully, this time. But there it is: it can't be managed. She was his brother's wife. Their union has offended divine law.

You can hear what Katherine says. That wreck of a body, held together by lacing and stays, encloses a voice that you can hear as far as Calais: it resounds from here to Paris, from here to Madrid, to Rome. She is standing on her status, she is standing on her rights; the windows are rattled, from here to Constantinople.

What a woman she is, Thomas Cromwell remarks in Spanish: to no one in particular.

By mid-July the cardinal is making his preparations for the voyage across the Narrow Sea. The warm weather has brought sweating sickness to London, and the city is emptying. A few have gone down already and many more are imagining they have it, complaining of headaches and pains in their limbs. The gossip in the shops is all about pills and infusions, and friars in the streets are doing a lucrative trade in holy medals. This plague came to us in the year 1485, with the armies that brought us the first Henry Tudor. Now every few years it fills the graveyards. It kills in a day. Merry at breakfast, they say: dead by noon.

So the cardinal is relieved to be quitting the city, though he cannot embark without the entourage appropriate for a prince of the church. He must persuade King François of the efforts he should make, in Italy, to free Pope Clement by military action; he must assure François of the King of England's amity and assistance, but without committing any troops or funds. If God gives him a following wind, he will bring back not only an annulment, but a treaty of mutual aid between England and France, one which will make the young Emperor's large jaw quiver, and draw a tear from his narrow Habsburg eye.

So why is he not more cheerful, as he strides about his private chamber at York Place? ‘What will I get, Cromwell, if I gain everything I ask? The queen, who does not like me, will be cast off and, if the king persists in his folly, the Boleyns brought in, who do not like me either; the girl has a spite against me, her father I've made a fool of for years, and her uncle, Norfolk, would see me dead in a ditch. Do you think this plague will be over by the time I return? They say these visitations are all from God, but I can't pretend to know his purposes. While I'm away you should get out of the city yourself.’

He sighs; is the cardinal his only work? No; he is just the patron who demands the most constant attendance. Business always increases. When he works for the cardinal, in London or elsewhere, he pays his own expenses and those of the staff he sends out on Wolsey business. The cardinal says, reimburse yourself, and trusts him to take a fair percentage on top; he doesn't quibble, because what is good for Thomas Cromwell is good for Thomas Wolsey – and vice versa. His legal practice is thriving, and he is able to lend money at interest, and arrange bigger loans, on the international market, taking a broker's fee. The market is volatile – the news from Italy is never good two days together – but as some men have an eye for horseflesh or cattle to be fattened, he has an eye for risk. A number of noblemen are indebted to him, not just for arranging loans, but for making their estates pay better. It is not a matter of exactions from tenants, but, in the first place, giving the landowner an accurate survey of land values, crop yield, water supply, built assets, and then assessing the potential of all these; next, putting in bright people as estate managers, and with them setting up an accounting system that makes yearly sense and can be audited. Among the city merchants, he is in demand for his advice on trading partners overseas. He has a sideline in arbitration, commercial disputes mostly, as his ability to assess the facts of a case and give a swift impartial decision is trusted here, in Calais and in Antwerp. If you and your opponent can at least concur on the need to save the costs and delays of a court hearing, then Cromwell is, for a fee, your man; and he has the pleasant privilege, often enough, of sending away both sides happy.

These are good days for him: every day a fight he can win. ‘Still serving your Hebrew God, I see,’ remarks Sir Thomas More. ‘I mean, your idol Usury.’ But when More, a scholar revered through Europe, wakes up in Chelsea to the prospect of morning prayers in Latin, he wakes up to a creator who speaks the swift patois of the markets; when More is settling in for a session of self-scourging, he and Rafe are sprinting to Lombard Street to get the day's exchange rates. Not that he sprints, quite; an old injury drags sometimes, and when he's tired a foot turns inward, as if he's walking back towards himself. People suggest it is the legacy of a summer with Cesare Borgia. He likes the stories they tell about him. But where's Cesare now? He's dead.

‘Thomas Cromwell?’ people say. ‘That is an ingenious man. Do you know he has the whole of the New Testament by heart?’ He is the very man if an argument about God breaks out; he is the very man for telling your tenants twelve good reasons why their rents are fair. He is the man to cut through some legal entanglement that's ensnared you for three generations, or talk your sniffling little daughter into the marriage she swears she will never make. With animals, women and timid litigants, his manner is gentle and easy; but he makes your creditors weep. He can converse with you about the Caesars or get you Venetian glassware at a very reasonable rate. Nobody can out-talk him, if he wants to talk. Nobody can better keep their head, when markets are falling and weeping men are standing on the street tearing up letters of credit. ‘Liz,’ he says one night, ‘I believe that in a year or two we'll be rich.’

She is embroidering shirts for Gregory with a black-work design; it's the same one the queen uses, for she makes the king's shirts herself.

‘If I were Katherine I'd leave the needle in them,’ he says.

She grins. ‘I know you would.’

Lizzie had grown silent and stern when he told her how the king had spoken, at the meeting with Katherine. He had told her they should separate, pending a judgment on their marriage; perhaps she would retire from court? Katherine had said no; she said that would not be possible; she said she would seek advice from canon lawyers, and that he, himself, should equip himself with better lawyers, and better priests; and then, after the shouting was done, the people with their ears pressed to the walls had heard Katherine crying. ‘He doesn't like her crying.’

‘Men say,’ Liz reaches for her scissors, ‘“I can't endure it when women cry” – just as people say, “I can't endure this wet weather.” As if it were nothing to do with the men at all, the crying. Just one of those things that happen.’

‘I've never made you cry, have I?’

‘Only with laughter,’ she says.

Conversation fades into an easy silence; she is embroidering her own thoughts, he is plotting what to do with his money. He is supporting two young scholars, not belonging to the family, through Cambridge University; the gift blesses the giver. I could increase those endowments, he thinks, and – ‘I suppose I should make a will,’ he says.

She reaches out for his hand. ‘Tom, don't die.’

‘Good God, no, I'm not proposing it.’

He thinks, I may not be rich yet but I am lucky. Look how I got out from under Walter's boots, from Cesare's summer, and a score of bad nights in back alleys. Men, it is supposed, want to pass their wisdom to their sons; he would give a great deal to protect his own son from a quarter of what he knows. Where does Gregory's sweet nature come from? It must be the result of his mother's prayers. Richard Williams, Kat's boy, is sharp, keen and forward. Christopher, his sister Bet's boy, is clever and willing too. And then he has Rafe Sadler, whom he trusts as he would trust his son; it's not a dynasty, he thinks, but it's a start. And quiet moments like this are rare, because his house is full of people every day, people who want to be taken to the cardinal. There are artists looking for a subject. There are solemn Dutch scholars with books under their arms, and Lübeck merchants unwinding at length solemn Germanic jokes; there are musicians in transit tuning up strange instruments, and noisy conclaves of agents for the Italian banks; there are alchemists offering recipes and astrologers offering favourable fates, and lonely Polish fur traders who've wandered by to see if someone speaks their language; there are printers, engravers, translators and cipherers; and poets, garden designers, cabalists and geometricians. Where are they tonight?

‘Hush,’ Liz says. ‘Listen to the house.’

At first, there is no sound. Then the timbers creak, breathe. In the chimneys, nesting birds shuffle. A breeze blows from the river, faintly shivering the tops of trees. They hear the sleeping breath of children, imagined from other rooms. ‘Come to bed,’ he says.

The king can't say that to his wife. Or, with any good effect, to the woman they say he loves.

Now the cardinal's many bags are packed for France; his entourage yields little in splendour to the one with which he crossed seven years ago to the Field of the Cloth of Gold. His itinerary is leisurely, before he embarks: Dartford, Rochester, Faversham, Canterbury for three or four days, prayers at the shrine of Becket.

So, Thomas, he says, if you know the king's had Anne, get a letter to me the very day. I'll only trust it if I hear it from you. How will you know it's happened? I should think you'll know by his face. And if you have not the honour of seeing it? Good point. I wish I had presented you; I should have taken the chance while I had it.

‘If the king doesn't tire of Anne quickly,’ he tells the cardinal, ‘I don't see what you are to do. We know princes please themselves, and usually it's possible to put some gloss on their actions. But what case can you make for Boleyn's daughter? What does she bring him? No treaty. No land. No money. How are you to present it as a creditable match at all?’

Wolsey sits with his elbows on his desk, his fingers dabbing his closed lids. He takes a great breath, and begins to talk: he begins to talk about England.

You can't know Albion, he says, unless you can go back before Albion was thought of. You must go back before Caesar's legions, to the days when the bones of giant animals and men lay on the ground where one day London would be built. You must go back to the New Troy, the New Jerusalem, and the sins and crimes of the kings who rode under the tattered banners of Arthur and who married women who came out of the sea or hatched out of eggs, women with scales and fins and feathers; beside which, he says, the match with Anne looks less unusual. These are old stories, he says, but some people, let us remember, do believe them.

He speaks of the deaths of kings: of how the second Richard vanished into Pontefract Castle and was murdered there or starved; how the fourth Henry, the usurper, died of a leprosy which so scarred and contracted his body that it was the size of a mannikin or child. He talks of the fifth Henry's victories in France, and the price, not in money, to be paid for Agincourt. He talks of the French princess whom that great prince married; she was a sweet lady, but her father was insane and believed that he was made of glass. From this marriage – Fifth Henry and the Glass Princess – sprung another Henry who ruled an England dark as winter, cold, barren, calamitous. Edward Plantagenet, son of the Duke of York, came as the first sign of spring: he was a native of Aries, the sign under which the whole world was made.

When Edward was eighteen years old, he seized the kingdom, and he did it because of a sign he received. His troops were baffled and battle-weary, it was the darkest time of one of God's darkest years, and he had just heard the news that should have broken him: his father and his youngest brother had been captured, mocked and slaughtered by the Lancastrian forces. It was Candlemas; huddled in his tent with his generals, he prayed for the slaughtered souls. St Blaise's Day came: 3 February, black and icy. At ten in the morning, three suns rose in the sky: three blurred discs of silver, sparkling and hazy through particles of frost. Their garland of light spread over the sorry fields, over the sodden forests of the Welsh borderlands, over his demoralised and unpaid troops. His men knelt in prayer on the frozen ground. His knights genuflected to the sky. His whole life took wing and soared. In that wash of brilliant light he saw his future. When no one else could see, he could see: and that is what it means to be a king. At the Battle of Mortimer's Cross he took prisoner one Owen Tudor. He beheaded him in Hereford marketplace and set his head to rot on the market cross. An unknown woman brought a basin of water and washed the severed head; she combed its bloody hair.

From then on – St Blaise's Day, the three suns shining – every time he touched his sword he touched it to win. Three months later he was in London and he was king. But he never saw the future again, not clearly as he had that year. Dazzled, he stumbled through his kingship as through a mist. He was entirely the creature of astrologers, of holy men and fantasists. He didn't marry as he should, for foreign advantage, but became enmeshed in a series of half-made, half-broken promises to an unknown number of women. One of them was a Talbot girl, Eleanor by name, and what was special about her? It was said she was descended – in the female line – from a woman who was a swan.

And why did he fasten his affection, finally, on the widow of a Lancastrian knight? Was it because, as some people thought, her cold blonde beauty raised his pulse? It was not exactly that; it was that she claimed descent from the serpent woman, Melusine, whom you may see in old parchments, winding her coils about the Tree of Knowledge and presiding over the union of the moon and the sun. Melusine faked her life as an ordinary princess, a mortal, but one day her husband saw her naked and glimpsed her serpent's tale. As she slid from his grip she predicted that her children would found a dynasty that would reign for ever: power with no limit, guaranteed by the devil. She slid away, says the cardinal, and no one ever saw her again.

Some of the candles have gone out; Wolsey does not call for more lights. ‘So you see,’ he says, ‘King Edward's advisers were planning to marry him to a French princess. As I … as I have intended. And look what happened instead. Look how he chose.’

‘How long is that? Since Melusine?’

It is late; the whole great palace of York Place is quiet, the city sleeping; the river creeping in its channels, silting its banks. In these matters, the cardinal says, there is no measure of time; these spirits slip from our hands and through the ages, serpentine, mutable, sly.

‘But the woman King Edward married – she brought, did she not, a claim to the throne of Castile? Very ancient, very obscure?’

The cardinal nods. ‘That was the meaning of the three suns. The throne of England, the throne of France, the throne of Castile. So when our present king married Katherine, he was moving closer to his ancient rights. Not that anyone, I imagine, dared put it in those terms to Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand. But it is as well to remember, and mention from time to time, that our king is the ruler of three kingdoms. If each had their own.’

‘By your account, my lord, our king's Plantagenet grandfather beheaded his Tudor great-grandfather.’

‘A thing to know. But not to mention.’

‘And the Boleyns? I thought they were merchants, but should I have known they had serpent fangs, or wings?’

‘You are laughing at me, Master Cromwell.’

‘Indeed not. But I want the best information, if you are leaving me to watch this situation for you.’

The cardinal talks then about killing. He talks about sin: about what's to be expiated. He talks about the sixth King Henry, murdered in the Tower; of King Richard, born under Scorpio, the sign of secret dealings, tribulation and vice. At Bosworth, where the Scorpian died, bad choices were made; the Duke of Norfolk fought on the losing side, and his heirs were turned out of their dukedom. They had to work hard, long and hard, to get it back. So do you wonder, he says, why the Norfolk that is now shakes sometimes, if the king is in a temper? It's because he thinks he will lose all he has, at an angry man's whim.

The cardinal sees his man make a mental note; and he speaks of the loose rattling bones under the paving of the Tower, those bones bricked into staircases and mulched into the Thames mud. He talks about King Edward's two vanished sons, the younger of them prone to stubborn resurrections that almost threw Henry Tudor out of his kingdom. He speaks of the coins the Pretender struck, stamped with their message to the Tudor king: ‘Your days are numbered. You are weighed in the balance: and found wanting.’

He speaks of the fear that was then, of the return of civil war. Katherine was contracted to be married into England, had been called ‘Princess of Wales’ since she was three years old; but before her family would let her embark from Corunna, they exacted a price in blood and bone. They asked Henry to turn his attention to the chief Plantagenet claimant, the nephew of King Edward and wicked King Richard, whom he had held in the Tower since he was a child of ten. To gentle pressure, King Henry capitulated; the White Rose, aged twenty-four, was taken out into God's light and air, in order to have his head cut off. But there is always another White Rose; the Plantagenets breed, though not unsupervised. There will always be the need for more killing; one must, says the cardinal, have the stomach for it, I suppose, though I don't know I ever have; I am always ill when there is an execution. I pray for them, these old dead people. I even pray for wicked King Richard sometimes, though Thomas More tells me he is burning in Hell.