По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

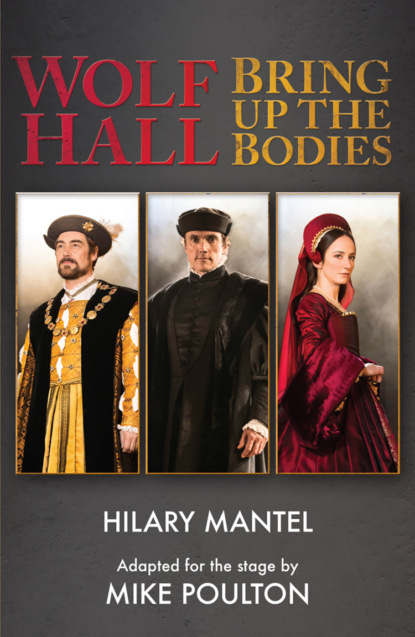

Wolf Hall & Bring Up the Bodies: RSC Stage Adaptation - Revised Edition

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Let’s think of you astrologically, because your contemporaries did. You are a native of Cancer the Crab and so never walk a straight line. You go sideways to your target, but when you have reached it your claws take a grip. You are both callous and vulnerable, hard-shelled and inwardly soft.

You are a charmer and you have been charming people since you were a baby, long before anyone knew you were going to be King. You were less than four years old when your father showed you off to the Londoners, perched alone on the saddle of a warhorse as you paraded through the streets.

Even as a child you behaved more like a king than your elder brother did. Arthur was dutiful and reserved, always with your father, whereas you were left with the women, a bonny, boisterous child, able to command attention. You were only ten when your brother married the Spanish Princess Katherine, but when you danced at the wedding, all eyes were on you.

At Arthur’s sudden death, your mother and father are plunged into deep grief and dynastic panic. It’s by no means sure that, were your father also to die now, you would come to the throne as the second Tudor; no one wants rule by a child. But your father battles on for a few more years, and you step into Arthur’s role gladly, an understudy who will play the part much better than the original cast member. Later, do you feel some guilt about this?

You are eighteen when you become King, a ‘virtuous prince’, seemingly a model for kingship; you are intellectually gifted, pious, a linguist, a brilliant sportsman, able to write a love song or compose a mass. Almost at once, you marry your brother’s widow and you execute your father’s closest advisers. The latter action is a naked bid for popularity, and it ought to give warning of the seriousness of your intent. Still, early in your reign you put more effort into hunting and jousting than to governing, with a bit of light warfare thrown in. You prefer to look like a king than be a king, which is why you let Thomas Wolsey run the country for you.

You are sexually inexperienced and will always be sexually shy; you don’t like dirty jokes. You have a few liaisons, but they are low-key and discreet. You never embarrass Katherine, who is too grand to display any jealousy, though she is too much in love with you not to care. However, you cosset and promote your illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy (a son you can acknowledge, as his mother was unmarried). Fitzroy has his own household, so is not part of the daily life of the Court, but is loaded with honours.

You are approaching forty when this story starts, five years younger than Thomas Cromwell. You are not ageing particularly well; still trim, still good-looking, you remain a superb athlete and jouster, but in an effort to hang on to your youth you have taken to collecting friends who are a generation younger than you, lively young courtiers like Francis Weston.

Your manner is relaxed, rather than domineering. You are highly intelligent, quick to grasp the possibilities of any situation. You expect to get your own way, not just because you are a king but because you are that sort of man. When you are thwarted, your charm vanishes. You are capable of a carpet-chewing rage, which throws people because it is so unexpected, and because you will turn on the people closest to you. But most of the time you like to be liked; you have no fear of confronting men, though you don’t seek confrontation, but you will not confront a woman, so you are run ragged between Katherine and Anne, trying to placate one and please the other. Unlike most men of your era, you truly believe in romantic love (though, of course, not in monogamy). It is an ideal for you. You were in love with Katherine when you married her and when you fall in love with Anne Boleyn you feel you must shape your life around her. Likewise, when Jane Seymour comes along…

When you ask Katherine for an annulment, you are not (in the view of your advisers) asking for anything outrageous. The Pope is usually keen to please royalty, and there are recent precedents in both your families. The timing is what’s wrong; the troops of Katherine’s nephew the Emperor march into Rome and the Pope is no longer free to decide. You are outraged when Katherine resists you and Wolsey fails you. You believe in your own case; you are a keen amateur theologian, and you think you know what God wants.

You are highly emotional. You are religious, superstitious, vulnerable to panic. Because you are so afraid of dying without an heir you’ve become a hypochondriac, and gradually a sort of self-pity has corrupted your character. You are so different from Cromwell that there’s probably little natural sympathy between you; you get your brotherly love from Archbishop Cranmer. But you need Cromwell as a stabilising force. You can carry on being loved by your people, as long as he will carry your sins for you. He begins by amusing and impressing you, proceeds by making you rich, and ends by frightening you. When, in 1540, you are told by Cromwell’s enemies that he intends to turn you out and become King himself, you completely believe it. For a few weeks, anyway. Then, as soon as his head is off, you want him back. It’s the Wolsey story over again. Who is to blame? Definitely not you.

ANNE BOLEYN

You do not have six fingers. The extra digit is added long after your death by Jesuit propaganda. But in your lifetime you are the focus of every lurid story that the imagination of Europe can dream up. From the moment you enter public consciousness, you carry the projections of everyone who is afraid of sex or ashamed of it. You will never be loved by the English people, who want a proper, royal Queen like Katherine, and who don’t like change of any sort. Does that matter? Not really. What Henry’s inner circle thinks of you matters far more. But do you realise this? Reputation management is not your strong point. Charm only thinly disguises your will to win.

You are the most sophisticated woman at Henry’s Court, with polished manners and just the suggestion of a French accent. Unlike your sister Mary, you have kept your name clean. You are elegant, reserved, self-controlled, cerebral, calculating and astute. But you are (especially as the story progresses) inclined to frayed nerves and shaking hands. You are quick-tempered and, like anyone under pressure, you can be highly irrational. You look at people to see what use can be got out of them, and you immediately see the use of Thomas Cromwell.

You come to the English Court in your early twenties, but you are in your late twenties before you catch Henry’s attention, and ours in the plays. Your contemporaries did not think you were pretty because they admired pink-and-white blonde beauty, and you (judging by their descriptions) were dark and slender. This difference becomes part of your distinction. It’s your vitality that draws the eye. You sing beautifully and dance whenever you can. You are the leader of fashion at the Court, before you become Queen.

When you are first at Court you become involved with Harry Percy, the heir to the Earldom of Northumberland. In the strictly regulated hierarchy of Court marriages, he is ‘above’ you, and is already promised to the daughter of the Earl of Shrewsbury. Cardinal Wolsey steps in and makes Harry Percy go ahead with the Shrewsbury marriage. It’s at this point, your detractors will say, that you start to hate Wolsey and look for revenge. As far as the Cardinal is concerned, it’s nothing personal. But it wouldn’t be surprising if you took it personally. Harry Percy will later claim you had made a promise of marriage before witnesses, which would count as binding. At the time you are silent about the business. Whether you had feelings for Harry Percy, or were acting out of ambition, is not clear.

When the King makes his first approaches you are wary because you don’t intend to be a discarded mistress, like your sister Mary. You make him keep his distance and work hard for a smile. To think that you, a knight’s daughter, could replace the Queen of England is an idea so audacious that it takes a while for the rest of Europe to catch up with it. It’s assumed that, once Henry’s divorce comes through, he will marry a French princess. You are Wolsey’s downfall; for a long time, though he remembers you exist, he doesn’t know you’re important to the King. As far as he is concerned, he has finished his dealings with you when he makes Harry Percy reject you. There was a time when the King told Wolsey everything. But since you came along, that age has passed.

Your campaign to be Queen is fought with patience and cunning. Saying ‘no’ to Henry is a profitable business and you are made Marquise of Pembroke. There is a point when, after you feel Henry has committed himself to you, you’d probably be willing to go to bed with him; but by that time, he’s intent on remaining apart until you are married. He says you have promised him a son, and he wants to be right with his conscience and with God. Any child you have must be born within your marriage. You marry secretly in Calais, at the end of 1532, and a few weeks later, with no fuss, on English soil. Elizabeth is born the September following. Though Henry is disappointed not to have a boy, he doesn’t (as myth suggests) turn against you. He is glad to have a healthy child after losing so many, and confident of a boy next time.

Are you really a religious woman, a convinced reformer? No one will ever know. It’s probable that you picked up your ideas at the French Court, where the intellectual as well as the moral climate is freer. There’s nothing to gain for you in being a faithful daughter of Rome. The texts you put Henry’s way are self-serving, in that they suggest the subject should be obedient to the secular ruler, not to the Pope. But you go to some trouble to protect and promote evangelicals. ‘My bishops’, as you call them, are your war leaders against the old order.

Your family – your father, Thomas Boleyn, and your uncle the Duke of Norfolk – expect that, if they back you as Henry’s second wife, it will be to the family’s advantage, and they will be your advisers and indeed controllers. They are shocked to find that, once Queen, you consider yourself the head of the family. They begin to distance themselves from you as you ‘fail’ Henry by not providing a son, but your brother George is close to you and always loyal. Your sister Mary has a shrewd idea of what is going on; after the first blaze of triumph, you are unhappy.

You expected to be Henry’s confidante and adviser, as Katherine was in the early days of the first marriage. But Henry is less open now, and his problems (many of them caused by your marriage) are new and seem intractable. Gradually you realise that Cromwell, whom you regarded as your servant, is accreting more and more power and that he has his own agenda and his own interests.

Meanwhile, you are locked into an unwinnable contest with Henry’s teenage daughter Mary. She will never acknowledge you as Queen, even after her mother is dead. From time to time your temper makes you threaten her. No one knows whether you mean your threats, but it’s widely believed you would harm her if you could.

After Elizabeth’s birth you miscarry at least one, maybe two children. Henry feels he has staked everything on a marriage that, despite his best efforts, no one in Europe recognises. You start to quarrel. Ambassador Chapuys gleefully retails each public row in dispatches. Cromwell warns the Ambassador not to make too much of it; you have always quarrelled and made up. But, unlike Katherine, you don’t take it quietly when Henry looks at other women. That he would become interested in someone as mousy as Jane Seymour seems like an insult.

Besides, you are bored. You were always cooler than the King and perhaps irritated by his adoration. He is not a good lover. You collect around you a group of admiring men who are good for your ego. You don’t see the danger in what becomes an explosive situation. Or perhaps you do see it, but still you crave the excitement.

Meanwhile, nothing good is happening to your looks. Ambassador Chapuys describes you as ‘a thin old woman’ at thirty-five. There is only one attested contemporary portrait, a medallion, not a picture. In it you can clearly see a swelling in your throat, which was noticed by your contemporaries, who also called you ‘a goggle-eyed whore’. To our mind, this suggests a hyperthyroid condition. You are nervous and jittery, outside and inside. There’s something feverish and desperate about your energy. You can’t control it and you are wearing yourself out.

At some point on the summer progress of 1535 you become pregnant again. At the end of January, on the day of Katherine’s funeral, you lose the child, a boy. (Contrary to the myth that’s taken hold, there is no evidence that the child was abnormal.) In the opinion of Ambassador Chapuys: ‘She has miscarried of her saviour.’ You celebrated when you heard of Katherine’s death, but it is not really good news for you. In the eyes of Catholic Europe, the King is now a widower, and free.

You are now in trouble. You are right in thinking you are surrounded by enemies. Nothing you could do would ever reconcile the old nobility to your status, and the tactless and noisy rise of your family has cut across many established interests. Katherine’s old friends and supporters are beginning to conspire in corners, and make overtures to Cromwell. Will he support the restoration of the Princess Mary to the succession, if they back him in a coup against you?

When Henry decides he wants to be free, the idea is to nullify the marriage, not to kill you. The canon lawyers go into a huddle with Cromwell. Then the whole business is accelerated and becomes public, because in late April 1536 you quarrel with Henry Norris; and afterwards you visibly panic, giving the impression of a woman who has something to hide. Everything you say is keenly noted and carried to the King, who immediately concludes you have been unfaithful to him. Cromwell is talking to your ladies-in-waiting. It’s possible that, even at this stage, he is not sure how he will bring the matter to a crisis. But when you are arrested you break down and talk wildly, supplying yourself the material for the charges against you.

By the time of your trial and your death you have collected yourself and are, according to Cromwell, ‘brave as a lion’.

KATHERINE OF ARAGON

Thomas Cromwell: ‘If she had been a man, she would have been a greater hero than all the generals of antiquity.’

You are the daughter of two reigning monarchs, Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile. Your father was known for his political cunning and your mother for her unfeminine fighting spirit. When you are told that you have failed, because you have only given Henry a daughter, and a woman can’t reign, there must be a part of you that asks, ‘Why not?’ Another part of you understands; though you are highly educated, you are conventional and accept what your religion tells you: that women, after God, must obey men. This is a conflict that will run through your life.

You have known since you were a small child that you were destined for an English alliance, and even in your nursery you were addressed as ‘the Princess of Wales’. You are an object of prestige for the Tudors, who are a new and struggling dynasty with a weak claim to England. At fifteen you come to England to marry Prince Arthur. You are beautiful and much admired, tiny, fair-skinned, auburn-haired. You are sent to Ludlow to hold court as Prince and Princess of Wales. Within a few weeks, Arthur is dead. You will always say that your marriage was never consummated. Some of your contemporaries, and some historians, don’t believe you. Perhaps you are not above a strategic lie. Your parents would have told one and not blinked.

Now you enter a bleak period of widowhood. King Henry VII doesn’t want you to go back to Spain. You’re his prize, and he wants to keep your dowry. After he is widowed, he thinks of marrying you himself, a project your family firmly veto. You remain in London, without enough money, uncertain of your status, on the very fringe of the Court. Your salvation comes when Arthur’s seventeen-year-old brother succeeds to the throne. It’s like all the fairytales rolled into one. After a period of seven years, the handsome prince rescues you. He loves you madly. You adore him.

And you always will. Whatever happens, it’s not really Henry’s fault. It’s always someone else, someone misleading him, someone betraying him. It’s Wolsey, it’s Cromwell, it’s Anne Boleyn.

You look like an Englishwoman and, as Queen, an Englishwoman is what you set out to become. When Henry goes to France for a little war, he has such faith in you that he leaves you as Regent. All the same, the King’s advisers suspect your intentions. You act as an unofficial ambassador for your country, and are ruthless in pushing the interests of Spain, a great power which at this time also rules the Netherlands. Your nephew, Charles V of Spain, becomes Holy Roman Emperor, making him overlord to the German princes, in territories where new religious ideas are taking a hold. You are not responsive to these ideas. You come from a land where the Inquisition is flourishing, and though your parents have reformed Spain’s administration, they have done it in a way that consolidates royal power. Probably you never understand why Henry has to listen to Parliament, or why he might want popular support.

At first you are Henry’s great friend as well as his lover. Then politics sours the relationship; Henry and Wolsey have to move adroitly between the two great power blocs of France and Spain, making sure they never ally and crush English interests. And your babies die. There are six pregnancies at least, possibly several more; the Tudors didn’t announce royal pregnancies, still less miscarriages, if they could be hidden. They only announced the happy results: a live, healthy child. You have only one of these, your daughter Mary.

You are older than Henry by seven years. And the pregnancies take their toll on your body. You become a stout little person, but you are always magnificently dressed and bejewelled; a queen must act like a queen. You are watched for signs that your fertile years are over. When Henry decides he must marry again, the intrigues develop behind your back. You are not at first aware, and nor is anyone else, that Henry has a woman in mind and that woman is Anne Boleyn. You believe he wants to replace you with a French princess, for diplomatic advantage, and you blame Wolsey, who you have always seen as your enemy; for years he has been your rival for influence with the King. You think you understand Henry. But for years he’s been drifting away from you, the boy with his sunny nature becoming a more complex and unhappy man.

Once the divorce plan is out in the open, no notion of feminine obedience or meekness constrains you. You fight untiringly and with every weapon you can find, legal and moral. The King says that Scripture forbids marriage with a brother’s wife. You insist that you were never Prince Arthur’s wife, that you lay in bed together as two good children, saying your prayers. You also believe that even if you and Arthur had consummated your marriage, you are still legally married to Henry; the Pope’s dispensation covered both cases.

No settlement is in sight. You are offered the option of retiring to a convent; if you were to become a nun, your marriage would be annulled in canon law, and, given that you are deeply religious, Henry hopes that might suit you. But as far as you are concerned, your vocation is to be Queen of England, and that is the estate to which God has called you, and you and God will make no concessions. You are always dignified, but you will not negotiate and you will concede nothing.

You are sent to a series of country houses: not shabby or unhealthy, as the legend insists, but remote, well away from any seaports. You are separated from your daughter, which agonises you, because she is in frail health and also you fear that she will be pressured into accepting that she is illegitimate. Though you are provided with a household to fit your status, you live in virtual isolation because you will not answer to your new style of ‘Dowager Princess of Wales’ and insist on being addressed as Queen. Soon you have confined yourself to one room, and your trusted maids cook for you over the fire. Henry sends Norfolk and Suffolk to bully you, without result. Finally you are divorced in your absence. You die in January 1536, after an illness of several months’ duration, probably a cancer. The rumours are, of course, that Anne Boleyn has poisoned you.

Cromwell’s admiration for you is on the record: even though his life would have been made simpler if you had just vanished, he admired your sense of battle tactics and your stamina in fighting a war you could not win. His approach is pragmatic and rational; he’s not a hater. You understand this. You may think, as much of Catholic Europe does, that he is the Antichrist. But you write to him in Spanish, addressing him as your friend.

PRINCESS MARY

Born seven years into your parents’ marriage, you are the only surviving child. You are in your mid-teens when you appear in this story. You are small, plain, pious and fragile: very clever, very brave, very stubborn. You hate Anne Boleyn, and revere your father, following your mother’s line in believing that he is misled. When you are separated from Katherine, and kept under house arrest, you are physically ill and suffer emotional desolation. You believe when Anne is executed that all your troubles are over. You are stunned to find that your father still requires you to acknowledge your illegitimacy and to recognise him as Head of the Church. You resist to the point of danger. Thomas Cromwell talks you back from the brink. Your dazed, ambivalent relation with him begins in these plays.

STEPHEN GARDINER

Cambridge academic, Master of Trinity Hall, you are in your late thirties as this story begins, and secretary to Cardinal Wolsey, who admires your first-class mind, finds you extremely useful, and has little idea of the grievances you are accumulating. Tactless and bruisingly confrontational, you are physically and intellectually intimidating, and your subordinates and your peers are equally afraid of you. But you suspect Thomas Cromwell laughs at you, and you are possibly right. You can only stare with uncomprehending hostility as he talks his way into the highest favour with Wolsey first and then the King. Cromwell is at his ease in any situation. You are the opposite, constantly bristling and tense.

Your origins are a mystery. You are brought up by respectable but humble parents, who are possibly your foster-parents. The rumour is that you are of Tudor descent through an illegitimate line, and so you are the King’s cousin. This may be why you get on in life; or it may be you are valued for your intellect; your personality is always in your way, and you seem helpless to do anything about it.

As you are politically astute and unhampered by gratitude, you begin to distance yourself from the Cardinal some months before his fall, and become secretary to the King. You are promoted to the bishopric of Winchester, the richest diocese in England. You are conservative in your own religious beliefs, but you are an authoritarian and a loyalist who will always back Henry, so you work hard for the divorce from Katherine, and you are all in favour of the King’s supremacy in Church and State. But Henry finds your company wearing; you always want to have an argument. And he likes people who can read his mood and respond to it.

So once again the pattern repeats; you are pushed out of the King’s favour by Cromwell, and have to watch him grow the secretary’s post into the most important job in the country (after king). Cromwell is generally so plausible that even Norfolk sometimes forgets to hate him. But you never forget.

During the years of his supremacy, Cromwell will keep you abroad as much as possible, as an ambassador. When you finally make common cause with the Duke of Norfolk, his other great enemy, you will be able to destroy him.

Cromwell suspects, and he’s right, that underneath all, you are a papist, and that, given a chance, a swing of political fortune, you would take England straight back to Rome. This proves true; in the reign of Mary Tudor, you grab your chance, become Lord Chancellor and start burning heretics.