По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

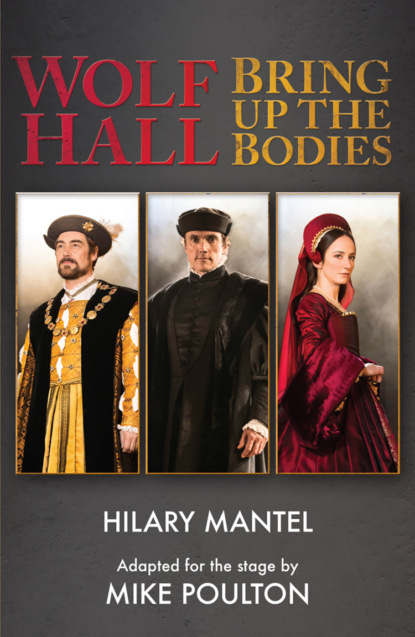

Wolf Hall & Bring Up the Bodies: RSC Stage Adaptation - Revised Edition

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Anne Boleyn is your damnation and Thomas Cromwell is your salvation. No one knows whether you and Anne were lovers. Only you know. No one is surprised that you are arrested with Anne’s ‘lovers’. You have been talked about for years and, to most people, you are the obvious suspect. What’s more remarkable is that you escape execution. Soon after your arrest, Cromwell assures your father that you will be coming home safely. He is confident of his ability to save you. But he must be confident you will give him something in return: evidence against Anne, which he will use if he has to. No such evidence emerges in court, as it is not needed. But you emerge into your future, not only free but with financial compensation.

There is no emotional compensation. You write ‘These bloody days have broke my heart.’ In the years after Anne’s death, England is an uncomfortable place for you. Cromwell sees you as a very clever man, but a man who feels too much. He sends you abroad on diplomatic missions, all of them uncomfortable and some of them dangerous. When you are away he looks after your business affairs. You come back to find yourself solvent and your papers in order. Soon you are in debt and disorder again.

When Cromwell walks to execution, you stand by the scaffold. He takes your hand and begs you to stop crying. You are the last person he speaks to. You go home and write a poem about it.

You are broken, disillusioned and worn out. You are dead before you’re forty.

GREGORY CROMWELL

You are in your late teens as this story unfolds. You are Thomas Cromwell’s only surviving child, and you are brought up as if you were a prince. You will be known to your contemporaries as ‘the gentle and virtuous Gregory’. Implacably sweet-natured, you seem to be bowed under the weight of all that is invested in you.

You spent your first years away from home under the indulgent care of a Benedictine nun, who lobbied for you to stay with her until you were twelve. But at some stage your father decided you had to grow up and learn proper Latin, and everything else his son was going to need to know. A distracting series of tutors follow. You are being prepared for a career in public life. You are really only interested in hunting and going out with your dogs.

Your father ascends the career ladder and you have to turn into a courtier. You are surprisingly good at this, a perfect young gentleman and a star in the tiltyard. (Your elder cousin Richard is also a formidable jouster, which must be a source of grief to the young noblemen who have prepared for the dangerous sport all their lives, and feel born to win.) The important thing is, the King likes you.

You will marry the sister of Jane Seymour. (So the blacksmith’s grandson is related to the King.) This family connection saves you when your father is executed. Richard Cromwell is a tougher character than you are, much more of a player, and his career is over, but though you do not inherit your father’s title of Earl, you are granted a baron’s title, and as Lord Cromwell you live and die a country gentleman, fathering many children and making a negligible impact on national life.

How could you possibly have lived up to expectations? In the third Cromwell novel, you will say to your father, ‘You know everything. You do everything. You are everything. What’s left for me?’

JANE BOLEYN, LADY ROCHFORD

We have to read you backwards, from your death on the scaffold eight years after the action of these plays. Possibly we are being unfair to you. But it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that you were a strange and dangerous woman.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: