По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

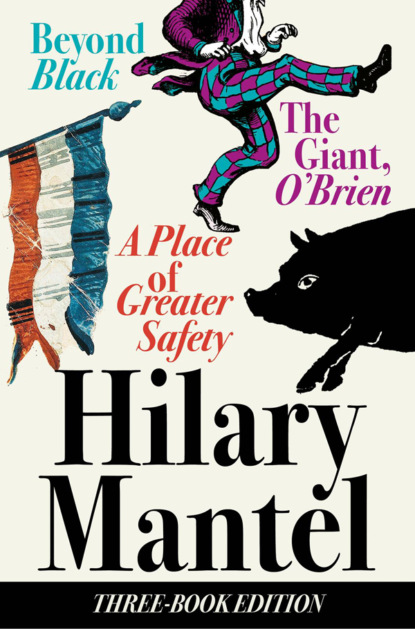

Three-Book Edition: A Place of Greater Safety; Beyond Black; The Giant O’Brien

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘The abbé did not speculate in grain.’ Claude held Camille in a red-faced inimical stare.

‘I do not suggest he did. I am paraphrasing the newspaper.’

‘Yes…of course.’ Claude looked away miserably.

‘Did you ever meet Terray?’ Camille asked his mother-in-law.

‘Once, I think. We exchanged about three words.’

‘You know,’ Camille said to Claude, ‘Terray did have a reputation with women.’

‘It wasn’t his fault.’ Claude flared up again. ‘He never wanted to be a priest. His family forced him into it.’

‘Do calm yourself,’ Annette suggested.

Claude hunched forward, hands pressed together between his knees. ‘Terray was our best hope. He worked hard. He had energy. People were afraid of him.’ He stopped, seeming to realize that for the first time in years he had added a new statement, a coda.

‘Were you afraid of him?’ Camille asked: not scoring a point, simply curious.

Claude considered. ‘I might have been.’

‘I’m quite often afraid of people,’ Camille said. ‘It’s a terrible admission, isn’t it?’

‘Like who?’ Lucile said.

‘Well, principally I’m afraid of Fabre. If he hears me stutter, he shakes me and takes me by the hair and bangs my head against the wall.’

‘Annette,’ Claude said, ‘there have been other imputations. In other newspapers.’ He looked covertly at Camille. ‘I have contrived to dismiss them from my mind.’

Annette made no comment. Camille hurled the Town and Court Journal across the room. ‘I’ll sue them,’ he said.

Claude looked up. ‘You’ll do what?’

‘I’ll sue them for libel.’

Claude stood up. ‘You’ll sue them,’ he said. ‘You. You’ll sue someone for libel.’ He walked out of the room, and they could hear his hollow laughter as he climbed the stairs.

FEBRUARY, Lucile was furnishing her apartment. They were to have pink silk cushions; Camille wondered how they would look a few months on, when grimy Cordeliers had mauled them. But he confined himself to an unspoken expletive when he saw her new set of engravings of the Life and Death of Maria Stuart. He did not like to look at these pictures at all. Bothwell had a ruthless, martial expression in his eye that reminded him of Antoine Saint-Just. Bulky retainers in bizarre plaids waved broadswords; kilted gentlemen, showing plump knees, helped the distressed Queen of Scots into a rowing boat. At her execution Maria was dressed to show off her figure, and looked all of twenty-three. ‘Crushingly romantic,’ Lucile said. ‘Isn’t it?’

Since they had moved, it was possible to run the Révolutions from home. Inky men, short-tempered and of a robust turn of phrase, stamped up and down the stairs with questions to which they expected her to know the answers. Uncorrected proofs tangled about table legs. Writ-servers sat around the street door, sometimes playing cards and dice to pass the time. It was just like the Danton house, which was in the same building round the corner – complete strangers tramping in and out at all hours, the dining room colonized by men scribbling, their bedroom an overflow sitting room and general thoroughfare.

‘We must order more bookcases made,’ she said. ‘You can’t have things in little piles all over the floor, I skid around when I get out of bed in the morning. Do you need all these old newspapers, Camille?’

‘Oh yes. They’re for searching out the inconsistencies of my opponents. So that I can persecute them when they change their opinions.’

He lifted one from a pile. ‘Hébert’s,’ she said. ‘That is dismal trash.’

René Hébert was peddling his opinions now through the persona of a bluff, pipe-smoking man of the people, a fictitious furnace-maker called Père Duchesne. The paper was vulgar, in every sense – simple-minded prose studded with obscenity. ‘Père Duchesne is a great royalist, isn’t he?’ Camille swiftly marked a passage. ‘I may have to hold that one against you, Hébert.’

‘Is Hébert really like Père Duchesne? Does he really smoke a pipe and swear?’

‘Not at all. He’s an effete little man. He has peculiar hands that flutter about. They look like things that live under stones. Listen, Lolotte – are you happy?’

‘Absolutely.’

‘Are you sure? Do you like the apartment? Do you want to move?’

‘No, I don’t want to move. I like the apartment. I like everything. I am very happy.’ Her emotions now seemed to lie just below the surface, scratching at her delicate skin to be hatched. ‘Only I’m afraid something will happen.’

‘What could happen?’ (He knew what could happen.)

‘The Austrians might come and you’d be shot. The Court might have you assassinated. You could be abducted and shut up in prison somewhere, and I’d never know where you were.’

She put up her hand to her mouth, as if she could stop the fears spilling out.

‘I’m not that important,’ he said. ‘They have more to do than arrange assassins for me.’

‘I saw one of those letters, threatening to kill you.’

‘That’s what comes of reading other people’s mail. You find out things you’d rather not know.’

‘Who obliges us to live like this?’ Her voice muffled against his shoulder. ‘Someday soon we’ll have to live in cellars, like Marat.’

‘Dry your tears. Someone is here.’

Robespierre hovered, looking embarrassed. ‘Your housekeeper said I should come through,’ he said.

‘That’s all right,’ Lucile gestured around her. ‘Not exactly a love-nest, as you see. Sit on the bed. Sit in the bed, feel free. Half of Paris was in here this morning while I was trying to get dressed.’

‘I can’t find anything since I moved,’ Camille complained. ‘And you’ve no idea how time-consuming it is, being married. You have to take decisions about the most baffling things – like whether to have the ceilings painted. I always supposed the paint just grew on them, didn’t you?’

Robespierre declined to sit. ‘I won’t stay – I came to see if you’d written that piece you promised, about my pamphlet on the National Guard. I expected to see it in your last issue.’

‘Oh Christ,’ Camille said. ‘It could be anywhere. Your pamphlet, I mean. Have you another copy with you? Look, why don’t you just write the piece yourself? It would be quicker.’

‘But Camille, it’s all very well for me to give your readers a digest of my ideas, but I expected something more – you could say whether you thought my ideas were cogent, whether they were logical, whether they were well-expressed. I can’t write a piece praising myself, can I?’

‘I don’t see the difficulty.’

‘Don’t be flippant. I haven’t time to waste.’

‘I’m sorry.’ Camille swept his hair back and smiled. ‘But you’re our editorial policy, didn’t you know? You’re our hero.’ He crossed the room, and touched Robespierre on the shoulder, very lightly, with just the tip of his middle finger. ‘We admire your principles in general, support your actions and writings in particular – and will therefore never fail to give you good publicity.’

‘Yet you have failed, haven’t you?’ Robespierre stepped back. He was exasperated. ‘You must try to keep to the task in hand. You are so heedless, you are unreliable.’

‘Yes, I’m sorry.’

She felt a needlepoint of irritation.