По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

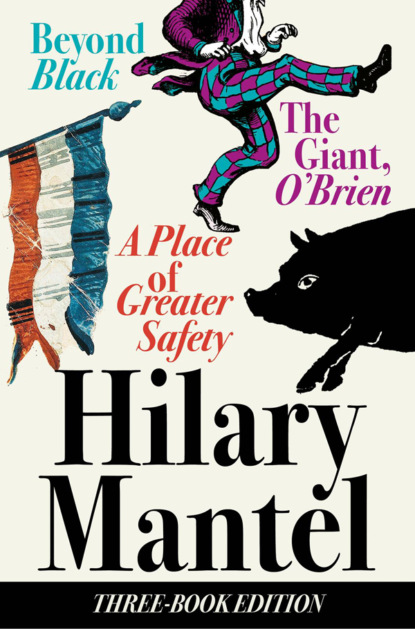

Three-Book Edition: A Place of Greater Safety; Beyond Black; The Giant O’Brien

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I don’t know. I could be. Most things are possible.’

‘You may wish to conciliate, but it is against your nature. You don’t work with people, you work over them.’

Danton nodded. He conceded the point. ‘I drive them as I wish,’ he said. ‘That could be towards moderation, or it could be towards the extremes.’

‘Yes, but the difficulty is, moderation looks like weakness, doesn’t it? Oh yes, I know, Danton, I have been here before you, crashing down this particular trail. And speaking of extremism, I do not care for the attacks on me made by your Cordeliers journalists.’

‘The press is free. I don’t dictate the output of the writers of my district.’

‘Not even the one who lives next door to you? I rather thought you did.’

‘Camille has to be running ahead of public opinion all the time.’

‘I can remember the days,’ Mirabeau said, ‘when we didn’t have public opinion. No one had ever heard of such a thing.’ He rubbed his chin, deep in thought. ‘Very well, Danton, consider yourself elected. I shall hold you to your promise of moderation, and I shall expect your support. Come now – tell me the gossip. How is the marriage?’

LUCILE looked at the carpet. It was a good carpet, and on balance she was glad she had spent the money on it. She did not particularly wish to admire the pattern now, but she could not trust the expression on her face.

‘Caro,’ she said, ‘I really can’t think why you are telling me all this.’

Caroline Rémy put her feet up on the blue chaise-longue. She was a handsome young woman, an actress belonging to the Théâtre Montansier company. She had two arrangements, one with Fabre d’Églantine and one with Hérault de Séchelles.

‘To protect you,’ she said, ‘from being told all this by unsympathetic people. Who would delight in embarrassing you, and making fun of your naïveté.’ Caroline put her head on one side, and wrapped a curl around her finger. ‘Let me see – how old are you now, Lucile?’

‘Twenty.’

‘Dear, dear,’ Caroline said. ‘Twenty!’ She couldn’t be much older herself, Lucile thought. But she had, not surprisingly, a rather well-used look about her. ‘I’m afraid, my dear, that you know nothing of the world.’

‘No. People keep telling me that, lately. I suppose they must be right.’ (A guilty capitulation. Camille, last week, trying to educate her: ‘Lolotte, nothing gains truth by mere force of repetition.’ But how to be polite, faced with such universal insistence?)

‘I’m surprised your mother didn’t see fit to warn you,’ Caro said. ‘I’m sure she knows everything there is to know about Camille. But if I’d had the courage – and believe me I reproach myself – to come to you before Christmas, and tell you, just for instance, about Maître Perrin, what would your reaction have been?’

Lucile looked up. ‘Caro, I’d have been riveted,’

It was not the answer Caro had expected. ‘You are a strange girl,’ she said. Her expression said clearly, strangeness doesn’t pay. ‘You see, you have to be prepared for what lies ahead of you.’

‘I try to imagine,’ Lucile said. She wished for the door to smash open, and one of Camille’s assistants to come flying in, and start firing off questions and rummaging for a piece of paper that had been mislaid. But the house was quiet for once: only Caro’s well-trained voice, with its tragedienne’s quaver, its suggestion of huskiness.

‘Infidelity you can endure,’ she said. ‘In the circles in which we move, these things are understood.’ She made a gesture, elegant fingers spread, to indicate the laudable correctness, both aesthetic and social, of a little well-judged adultery. ‘One finds a modus vivendi. I have no fear of your not being able to amuse yourself. Other women one can cope with, provided they’re not too close to home – ’

‘Just stop there. What does that mean?’

Caro became a little round-eyed. ‘Camille is an attractive man,’ she said. ‘I know whereof I speak.’

‘I don’t see what it has to do with anything,’ Lucile muttered, ‘if you’ve been to bed with him. I could do without that bit of information.’

‘Please regard me as your friend,’ Caro suggested. She bit her lip. At least she had found out that Lucile was not expecting a child. Whatever the reason for the hurry about the marriage, it was not that. It must be something even more interesting, if she could only make it out. She patted her curls back into place and slid from the chaise-longue. ‘Must go. Rehearsal.’

I don’t think you need any rehearsal, Lucile said under her breath. I think you’re quite perfect.

WHEN CARO had gone, Lucile leaned back in her chair, and tried to take deep breaths, and tried to be calm. The housekeeper, Jeanette, came in, and looked her over. ‘Try a small omelette,’ she advised.

‘Leave me alone,’ Lucile said. ‘I don’t know why you think that food solves everything.’

‘I could step around and fetch your mother.’

‘I should just think,’ Lucile said, ‘that I can do without my mother at my age.’

She agreed to a glass of iced water. It made her hand ache, froze her deep inside. Camille came in at a quarter-past five, and ran around snatching up pen and ink. ‘I have to be at the Jacobins,’ he said. That meant six o’clock. She stood over him watching his scruffy handwriting loop itself across the page. ‘No time ever to correct…’ He scribbled. ‘Lolotte…what’s wrong?’

She sat down and laughed feebly: nothing’s wrong.

‘You’re a terrible liar.’ He was making deletions. ‘I mean, you’re no good at it.’

‘Caroline Rémy called.’

‘Oh.’ His expression, in passing, was faintly contemptuous.

‘I want to ask you a question. I appreciate it might be rather difficult.’

‘Try.’ He didn’t look up.

‘Have you had an affair with her?’

He frowned at the paper. ‘That doesn’t sound right.’ He sighed and wrote down the side of the page. ‘I’ve had an affair with everybody, don’t you know that by now?’

‘But I’d like to know.’

‘Why?’

‘Why?’

‘Why would you like to know?’

‘I can’t think why, really.’

He tore the sheet once across and began immediately on another. ‘Not the most intelligent of conversations, this.’ He wrote for a minute. ‘Did she say that I did?’

‘Not in so many words.’

‘What gave you the idea then?’ He looked up at the ceiling for a synonym, and as he tipped his head back the flat, red winter light touched his hair.

‘She implied it.’

‘Perhaps you mistook her.’

‘Would you mind just denying it?’

‘I think it’s quite probable that at some time I spent a night with her, but I’ve no clear memory of it.’ He had found the word, and reached for another sheet of paper.