По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

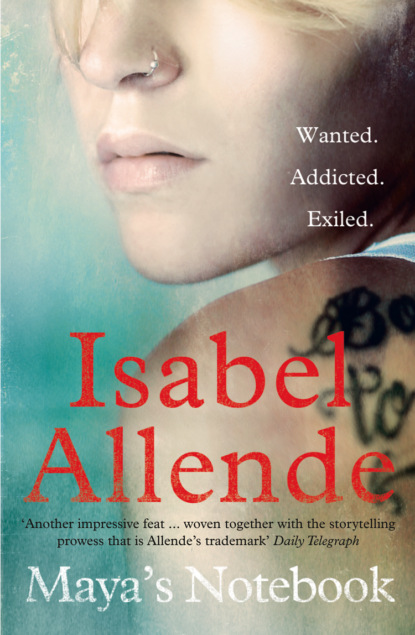

Maya’s Notebook

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Fleeing from the authorities,” I answered seriously, and he burst out laughing.

“I spent sixteen years doing the very same thing, and to be honest, I miss those days.”

He and Manuel Arias have been friends since 1975, when they were both banished to Chiloé. Being sentenced to banishment, or relegation, as it’s called in Chile, is very harsh, but less so than exile, because at least the convict is in his own country, he told me.

“They sent us far away from our families, to some inhospitable place where we were alone, with no money or work, harassed by the police. Manuel and I were lucky, because we got sent to Chiloé and the people here took us in. You won’t believe me, child, but Don Lionel Schnake, who hated leftists more than the devil, gave us free room and board.”

In that house Manuel met Blanca, the daughter of his kind-hearted host. Blanca was in her early twenties, engaged, and her beauty was commented on by everyone, attracting a pilgrimage of admirers, who weren’t intimidated by the fiancé.

Manuel was in Chiloé for a year, barely earning his keep as a fisherman and carpenter, while he read about the fascinating history and mythology of the archipelago without leaving Castro, where he had to present himself daily at the police station to sign in. In spite of the circumstances, he grew attached to Chiloé; he wanted to travel all over it, study it, tell its stories. That’s why, after a long journey all over the world, he came back to live out his days here. After serving his sentence, he was able to go to Australia, one of the countries that took in Chilean refugees, where his wife was waiting for him. I was surprised to hear that Manuel had a family; he’d never mentioned it. It turns out he’d been married twice, didn’t have any kids, had also been divorced twice, a long time ago; neither of the women lives in Chile.

“Why did you get banished, Manuel?” I asked.

“The military closed the Faculty of Social Sciences, where I was a professor, because they considered it a den of Communists. They arrested lots of professors and students, killed some of them.”

“Were you arrested?”

“Yes.”

“And my Nini? Do you know if they arrested her?”

“No, not her.”

How is it possible that I know so little about Chile? I don’t dare ask Manuel, as I don’t want to seem ignorant, so I started to dig around on the Internet. Thanks to the free flights my dad got us because he’s a pilot, my grandparents took me on trips for every school holiday and summer vacation. My Popo made a list of places we should see after Europe and before we died. So we visited the Galápagos Islands, the Amazon, Cappadocia, and Machu Picchu, but we never came to Chile, as might have been logical. My Nini’s lack of interest in visiting her country is inexplicable; she ferociously defends her Chilean customs and still gets emotional when she hangs the tricolor flag from her balcony in September. I think she cultivates a poetic idea of Chile and fears confronting reality—or there may well be something here she doesn’t want to remember.

My grandparents were experienced and practical travelers. In our photo albums the three of us appear in exotic places always wearing the same clothes, because we’d reduced our baggage to the bare minimum. We each kept one piece of hand luggage packed, ready to go, so we could leave within half an hour, should the opportunity or a whim arise. Once my Popo and I were reading about gorillas in National Geographic, how they’re gentle vegetarians and have strong family bonds, and my Nini, who was passing through the living room with a vase of flowers in her hands, commented offhand that we should go and see them. “Good idea,” answered my Popo, picked up the phone, called my dad, arranged the flights, and the next day we were on our way to Uganda with our battered little suitcases.

My Popo got invited to conferences and to give lectures, and whenever he could, he took us with him; my Nini feared some misfortune would befall us if we were separated. Chile is an eyelash between the mountains of the Andes and the depths of the Pacific Ocean, with hundreds of volcanoes, some with the lava still warm, that could wake up at any moment and bury the territory in the sea. This might explain why my Chilean grandmother always expects the worst. She’s always prepared for emergencies and goes through life with a healthy fatalism, supported by her favorite Catholic saints and the vague advice of her horoscope.

I used to miss a lot of classes, because I’d go traveling with my grandparents and because school got on my nerves; only my good marks and the flexibility of the Italian method kept me from getting expelled. I was extremely resourceful, and could fake appendicitis, migraine, laryngitis, and, if none of those worked, convulsions. My grandpa was easy to fool, but my Nini cured me with drastic methods, a freezing shower or a spoonful of cod-liver oil, unless it was in her interest that I miss school, for example, when she took me to protest against whatever war was on at the time, or put up posters in defense of laboratory animals, or chained us to a tree to piss off the logging companies. Her determination to inculcate me with a social conscience was always heroic.

On more than one occasion, my Popo had to go and rescue us from the police station. The police department in Berkeley is fairly indulgent, used to demonstrations in favor of all sorts of noble causes, fanatics with good intentions capable of camping for months in a public square, students determined to occupy the university in aid of Palestine or nudists’ rights, distracted geniuses who ignore traffic lights, beggars who in another life graduated summa cum laude, drug addicts looking for paradise—in short, to as many virtuous, intolerant, and combatant citizens as there are in this city of a hundred thousand inhabitants, where almost everything is permitted, as long as it’s done with good manners. My Nini and Mike O’Kelly tend to forget their good manners in the heat of battle in defense of justice, but if they do get arrested, they never end up in a cell. Instead, Sergeant Walczak personally goes and buys them cappuccinos.

I was ten when my dad remarried. He’d never introduced us to a single girlfriend and was such a champion of the advantages of independence that we never expected to see him give it up. One day he announced he was bringing a friend to dinner. My Nini, who for years had been secretly looking for girlfriends for him, prepared to try and make a good impression on this woman, while I prepared to attack her. A frenzy of activity was unleashed in the house: my Nini hired a professional cleaning service that left the air saturated with the smell of bleach and gardenias, and complicated her life with a Moroccan recipe for chicken with cinnamon that came out tasting like a dessert. My Popo recorded a selection of his favorite pieces so we’d have background music, which sounded to me like dentist’s waiting room music.

My dad, who we hadn’t seen for a couple of weeks, showed up on the appointed night with Susan, a freckle-faced and badly dressed blonde. This surprised us, because we had the idea that he liked glamorous women, like Marta Otter before she succumbed to motherhood and domestic life in Odense. Susan seduced my grandparents in just a few minutes with her easygoing nature, but not me; I was so rude to her that my Nini dragged me into the kitchen on the pretext of serving the chicken and offered me a couple of smacks if I didn’t change my attitude. After eating, my Popo committed the unthinkable crime of inviting Susan to the astronomical turret, where he never took anyone but me, and they were up there for a long time observing the sky, while my grandma and my dad scolded me for insolence.

A few months later, my dad and Susan were married in an informal ceremony on the beach. That sort of thing had gone out of fashion a decade earlier, but that’s what the bride wanted. My Popo would have preferred something a little more comfortable, but my Nini was in her element. A friend of Susan’s officiated, having obtained a mail-order license from the Universal Church. They forced me to attend, but I roundly refused to dress up as a fairy and present the rings, like my grandma wanted me to. My dad wore a white Mao suit that didn’t suit his personality or his political sympathies at all, and Susan wore a string of wildflowers in her hair and some diaphanous garment, also very passé. The guests, standing barefoot on the sand, shoes in hand, put up with half an hour of foggy weather and sugarcoated advice from the minister. Later there was a reception at the yacht club on the same beach and everybody danced and drank until after midnight, while I locked myself in my grandparents’ Volkswagen and only poked my nose out when good old O’Kelly came over in his wheelchair to bring me a piece of cake.

My grandparents expected the newlyweds would live with us, since we had more than enough room, but my dad rented a tiny little house in the same neighborhood that could have fit inside his mother’s kitchen, because he couldn’t afford anything better. Pilots work a lot, don’t earn very much, and are always tired; it’s not an enviable profession. Once they were settled in, my dad decided that I should live with them, and my tantrums didn’t soften him or frighten Susan, who at first glance had struck me as easy to intimidate. She was a levelheaded woman with an even temper, always ready to help, but without my Nini’s aggressive compassion, which tends to offend its beneficiaries.

Now I understand that Susan took on the thankless task of taking charge of a spoiled and fussy brat who’d been raised by old folks, who only tolerated white food—rice, popcorn, sliced bread, bananas—and spent the nights wide awake. Instead of forcing me to eat by traditional methods, she made me turkey breast with crème Chantilly, cauliflower with coconut ice cream, and other audacious combinations, until bit by bit I went from white to beige—hummus, some cereals, milky coffee—and from there to colors with more personality, like some tones of green, orange, and red, as long as it wasn’t beets. She wasn’t able to have children and tried to compensate for that lack by earning my affection, but I confronted her with the stubbornness of a mule. I left my things in my grandparents’ house and arrived at my dad’s only to sleep, with a bag in my hand, my alarm clock and whatever book I was reading. My nights were spent suffering from insomnia, trembling in fear, with my head buried under the covers. Since my dad would not have tolerated any rudeness, I opted for a haughty courtesy, inspired by butlers in British movies.

My only home was that big flamboyantly painted house where I went every day after school to do my homework and play, praying that Susan would forget to pick me up when she finished work in San Francisco, but that never happened: my stepmother had a pathological sense of responsibility. The whole first month went like that, until she brought a dog home to live with us. She worked for the San Francisco Police Department, training dogs to sniff out bombs, a highly valued specialty from 2001 onward, when the paranoia of terrorism began, but at the time when she married my dad she was the butt of her rough colleagues’ jokes; nobody had planted a bomb in California for ages.

Each animal worked with one single human for its whole life, and the two would eventually complement each other so well, they could guess each other’s thoughts. Susan selected the liveliest puppy of the litter and the person best suited to match up with the dog, someone who’d grown up with animals. Although I had sworn to destroy my stepmother’s nerves, I gave up when I saw Alvy, a six-year-old Labrador more intelligent and nicer than the best human being. Susan taught me everything I know about animals and allowed me, violating the fundamental rules of the manual, to sleep with Alvy. That’s how she helped me to tackle my insomnia.

The quiet presence of my stepmother came to be so natural and necessary in the family that it was hard to remember how life was before her. If my dad was traveling, in other words most of the time, Susan would give me permission to sleep over at my grandparents’ magical house, where my room remained intact. Susan loved my Popo. She went with him to see Swedish films from the 1950s, in black and white, without subtitles—you had to guess what the characters were saying—and to listen to jazz in pokey little dens thick with smoke. She treated my Nini, who is not at all docile, with the same method she used to train sniffer dogs: affection and firmness, punishment and reward. With affection she let her know she loved her and was at her beck and call; with firmness she prevented her from climbing in through the window of her house to inspect the level of cleanliness or give her granddaughter candies behind her back; she punished her by disappearing for days when my Nini overwhelmed her with gifts, unsolicited advice, and Chilean stews, and rewarded her by taking her for walks in the woods when everything was going well. She applied the same system to her husband and to me.

My good stepmother did not try to come between my grandparents and me, although the erratic way they were raising me must have shocked her. It’s true that they did spoil me, but that wasn’t the cause of my problems, as the psychologists I confronted in adolescence suspected. My Nini raised me the Chilean way, food and affection in abundance, clear rules and the occasional spanking, not many. Once I threatened to report her to the police for child abuse, and she hit me so hard with the soup ladle, she left a bump on my head. That stopped my initiative right in its tracks.

I attended a curanto, the typical abundant and generous feast of Chiloé, a community ceremony. The preparations started early, because the ecotourism boats arrive before noon. The women chopped tomatoes, onions, garlic, and cilantro for the seasoning and, using a tedious method, made milcao and chapalele, a sort of dough of potato, flour, lard, and pork crackling—disgusting, in my opinion—while the men dug a big pit, put a whole bunch of stones at the bottom, and lit a bonfire on top of them. By the time the wood had burned down, the stones were red-hot, coinciding with the arrival of the boats. The guides showed the tourists the village and gave them opportunities to buy knits, necklaces made of shells, myrtle-berry jam, licor de oro, wood carvings, snail-slime cream for age spots, lavender twigs—in short, the few things there are here—and soon they were gathered around the steaming pit on the beach. The curanto chefs set out clay pots on the stones to collect the broth, which is an aphrodisiac, as everyone knows, and piled on layers of the chapalele and milcao, pork, lamb, fish, chicken, shellfish, vegetables, and other delicacies I didn’t write down. Then they covered it with damp white cloths, huge nalca leaves, a big sack, which hung over the edges of the hole like a skirt, and finally sand. The cooking took a little over an hour, and while the ingredients were transforming in the secret heat, in their intimate juices and fragrances, the visitors entertained themselves by taking photographs of the smoke, drinking pisco, and listening to Manuel Arias.

The tourists fit into several categories: Chilean senior citizens, Europeans on vacation, a range of Argentineans and backpackers of vague origins. Sometimes a group of Asians would arrive, or Americans with maps, guides, and books of flora and fauna they consulted terribly seriously. All of them, except the backpackers, who preferred to smoke marijuana behind the bushes, appreciated the opportunity to listen to a published author, someone able to clarify the mysteries of the archipelago in either English or Spanish. Manuel is not always annoying; in small doses, he can be entertaining on his subject. He tells the visitors about the history, legends, and customs of Chiloé and warns them that the islanders are cautious, and must be won over bit by bit, with respect, just as you have to adapt gradually and respectfully to the wilderness, the implacable winters, and the whims of the sea. Slowly. Very slowly. Chiloé is not for people in a hurry.

People travel to Chiloé with the idea of going back in time, and they can be disappointed by the cities on Isla Grande, but on our little island they find what they’re looking for. There is no intention to deceive them on our part, of course; nevertheless, on curanto days oxen and sheep appear by chance near the beach, there are more than the usual number of nets and boats drying on the sand, people wear their coarsest hats and ponchos, and nobody would think of using their cell phone in public.

The experts knew exactly when the culinary treasures buried in the hole were cooked and shoveled off the sand, delicately lifted the sack, the nalca leaves, and the white cloths; then a cloud of steam with the delicious aromas of the curanto rose up to the sky. There was an expectant silence, and then a burst of applause. The women took out the pieces and served them on paper plates with more rounds of pisco sours, the most popular cocktail in Chile, strong enough to fell a Cossack. At the end we had to prop up several tourists on their way back to the boats.

My Popo would have liked this life, this landscape, this abundance of seafood, this lazy pace. He’d never heard of Chiloé, or he would have included it on his list of places to visit before he died. My Popo … how I miss him! He was a big, strong, slow and sweet bear, warm as an oven, with the scent of tobacco and cologne, a deep voice and quaking laugh, with enormous hands to hold me. He took me to soccer games and to the opera, answered my endless questions, brushed my hair and applauded my interminable epic poems, inspired by the Kurosawa films we used to watch together. We’d go up to the tower to peer through his telescope and scrutinize the black dome of the sky, searching for his elusive planet, a green star we were never able to find. “Promise me you’ll always love yourself as much as I love you, Maya,” he told me repeatedly, and I’d promise without knowing what that strange phrase meant. He loved me unconditionally, accepted me just as I am, with my limitations, peculiarities, and defects, he applauded even when I didn’t deserve it, as opposed to my Nini, who believes you shouldn’t celebrate children’s efforts, because they get used to it and then have a terrible time with real life, when no one praises them. My Popo forgave me for everything, consoled me, laughed when I laughed, was my best friend, my accomplice and confidant. I was his only granddaughter and the daughter he never had. “Tell me I’m the love of your life, Popo,” I’d ask him, to bug my Nini. “You’re the love of our lives, Maya,” he’d answer diplomatically, but I was his favorite, I’m sure of it; my grandma couldn’t compete with me. My Popo was incapable of choosing his own clothes—my Nini did that for him—but when I turned thirteen he took me to buy my first bra, because he noticed I was wrapped up in scarves and hunched over to hide my chest. I was too shy to talk about it to my Nini or Susan, but it seemed perfectly normal to try on bras in front of my Popo.

The house in Berkeley was my world: afternoons with my grandparents watching television, Sundays in the summertime having breakfast on the patio, the occasions when my dad arrived and we’d all have dinner together, while María Callas sang on old vinyl records, the desk, the books, the aromas in the kitchen. With this little family the first part of my existence went by without any problems worth mentioning, but at the age of sixteen the catastrophic forces of nature, as my Nini called them, agitated my blood and clouded my understanding.

I have the year my Popo died tattooed on my left wrist: 2005. In February we found out he was ill, in August we said good-bye, in September I turned sixteen and my family crumbled away.

The unforgettable day my Popo began to die, I’d stayed at school for the rehearsal of a play—Waiting for Godot no less, the drama teacher was ambitious—and then walked home to my grandparents’ house. It was dark by the time I got there. I walked in, calling them and turning on lights, surprised at the silence and the cold, because that was the house’s most welcoming time of day, when it was warm, there was music and the aromas from my Nini’s saucepans floated through the air. At that hour my Popo would be reading in the easy chair in his study and my Nini would be cooking while listening to the news on the radio, but I found none of that this evening. My grandparents were in the living room, sitting very close together on the sofa, which my Nini had upholstered following instructions from a magazine. They’d shrunk, and for the first time I noticed their age; until that moment they’d remained untouched by the rigors of time. I’d been with them day after day, year after year, without noticing the changes; my grandparents were immutable and eternal as the mountains. I don’t know if I’d only seen them through the eyes of my soul, or maybe they aged in those hours. I hadn’t noticed that my grandpa had lost weight over the last few months either; his clothes were too big for him, and my Nini didn’t look as tiny as she used to by his side.

“What’s up, folks?” and my heart leaped into empty space, because before they managed to answer me, I’d guessed. Nidia Vidal, that invincible warrior, was broken, her eyes swollen from crying. My Popo motioned me to sit down with them, hugged me, squeezing me against his chest, and told me he hadn’t been feeling well for a while, had been having stomachaches, and they’d done a number of tests on him and the doctor had just confirmed the cause. “What’s wrong with you, Popo?” and it came out like a scream. “Something to do with my pancreas,” he said, and his wife’s visceral moan let me know it was cancer.

Susan arrived about nine for dinner, as she often did, and found us huddled together on the sofa, shivering. She turned on the furnace, ordered a pizza, phoned my dad in London to give him the bad news, and then sat down with us, holding her father-in-law’s hand, in silence.

My Nini abandoned everything to take care of her husband: the library, the stories, the protest demonstrations, and the Club of Criminals. She even let her oven, which she’d kept warm during my entire childhood, grow cold. The cancer, that sly enemy, had attacked my Popo without any alarming signs until it was very advanced. My Nini took her husband to the Georgetown University Hospital, in Washington, where the best specialists are, but nothing worked. They told him it would be futile to operate, and he refused to undergo a bombardment of chemicals just to prolong his life a few months. I studied his illness on the Internet and in books I got out of the library and learned that of the 43,000 annual cases in the United States, more or less 37,000 are terminal; only 5 percent of patients respond to treatment, and for those the best they can hope for is to live another five years; in short, only a miracle would save my grandfather.

The week my grandparents spent in Washington, my Popo deteriorated so much that we barely recognized him when I went with my dad and Susan to pick them up at the airport. He’d lost even more weight, was dragging his feet, hunched over, his eyes yellow and his skin dull and ashen. With the hesitant steps of an invalid he walked to Susan’s van, sweating from the effort, and at home he didn’t have the energy to climb the stairs, so we made a bed up for him in his study on the first floor, where he slept until they brought in a hospital bed. My Nini got in with him, curled up at his side, like a cat.

My grandma confronted God to defend her husband with the same passion with which she embraced lost political and humanitarian causes, first with pleas, prayers, and promises, and then with curses and threats of becoming an atheist. “What good does it do us to fight against death, Nidia, when we always know who’s going to win, sooner or later?” my Popo teased her. Since traditional science could not help her husband, she resorted to alternative cures, like herbs, crystals, acupuncture, shamanism, aura massages, and even a little girl from Tijuana, with stigmata, said to work miracles. Her husband put up with these eccentricities with good humor, as he’d done ever since he met her. At first my dad and Susan tried to protect the old folks from the many charlatans who somehow got a whiff of the possibility of exploiting my Nini, but finally they accepted that these desperate measures kept her busy as the days went by.

In the final weeks I didn’t go to school. I moved into the big magic house with the intention of helping my Nini, but I was more depressed than the patient, and she had to take care of us both.

Susan was the first to dare mention a hospice. “That’s for dying people, and Paul is not going to die!” exclaimed my Nini, but little by little she had to give in. We started to get visits from Carolyn, a volunteer with a gentle manner and great expertise, to explain to us what was going to happen and how her organization could help us, at no cost, with everything from keeping the patient comfortable to providing spiritual or psychological comfort to us and dealing with the bureaucracy of the doctors and the funeral.

My Popo insisted on dying at home. The stages came and went in the order and at the pace that Carolyn predicted, but took me by surprise; just like Nini, I was expecting a divine intervention to change the course of our misfortune. Death happens to other people, not to the ones we love, and much less to my Popo, who was the center of my life, the force of gravity that anchored the world; without him I had no handle, I’d be swept away by the slightest breeze. “You swore to me you were never going to die, Popo!”

“No, Maya, I told you I would always be with you and I intend to fulfill my promise.”

The volunteers from the hospice set up the hospital bed in front of the big living room window, so at night my grandfather could imagine the stars and moon shining down on him, since he couldn’t see them through the branches of the pine trees. They inserted an IV port in his chest to administer his medicine without having to give him an injection every time and gave us instructions on how to move him, wash him, and change his sheets without getting him out of bed. Carolyn came to see him often, dealt with the doctor, the nurse, and the pharmacy; more than once she took charge of getting groceries, when no one in the family had the energy.

Mike O’Kelly visited us too. He arrived in his electric wheelchair, which he drove like a race car, often accompanied by a couple of his redeemed gang members, who he’d order to take out the garbage, vacuum, sweep the patio, and carry out other domestic tasks while he drank tea with my Nini in the kitchen. They’d been distant for a few months after fighting at a demonstration over abortion, which O’Kelly, an obedient Catholic, rejected, but my grandfather’s illness reconciled them. Although sometimes the two of them are at opposite ideological extremes, they can’t stay angry, because they love each other too much and have so much in common.

If my Popo was awake, Snow White would chat a while with him. They’d never developed a true friendship; I think they were each a bit jealous of the other. Once I heard O’Kelly talking about God to my Popo, and I felt obliged to warn him he was wasting his time, because my grandfather was an agnostic. “Are you sure, little one? Paul has spent his life observing the sky through a telescope. How could he not have caught a glimpse of God?” he answered me, but he didn’t try to save my grandfather’s soul against his will. When the doctor prescribed morphine and Carolyn let us know we’d have as much as we needed, because the patient had a right to die without pain and with dignity, O’Kelly abstained from warning us against euthanasia.

The inevitable moment arrived when my Popo ran out of strength and we had to call a halt to the procession of students and friends who kept coming to visit. He’d always been a bit of a dandy, and in spite of his weakness he worried about his appearance, although we were the only ones who saw him now. He asked us to keep him clean, shaven, and the room well ventilated; he was afraid of offending us with the miseries of his illness. His eyes were cloudy and sunken, his hands like a bird’s claws, his lips covered in sores, his skin bruised and hanging off his bones; my grandfather was the skeleton of a burned tree, but he could still listen to music and remember. “Open the window to let the joy in,” he’d ask us. Sometimes he was so far gone his voice was barely audible, but there were better moments, when we’d raise the back of the bed so he could sit up and talk with us. He wanted to pass his experiences and wisdom on to me before he left. He never lost his lucidity.

“Are you scared, Popo?” I asked him.

“No, but I’m sorry, Maya. I would have liked to live another twenty years with you two,” he answered.

“What will there be on the other side, Popo? Do you believe there’s life after death?”