По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

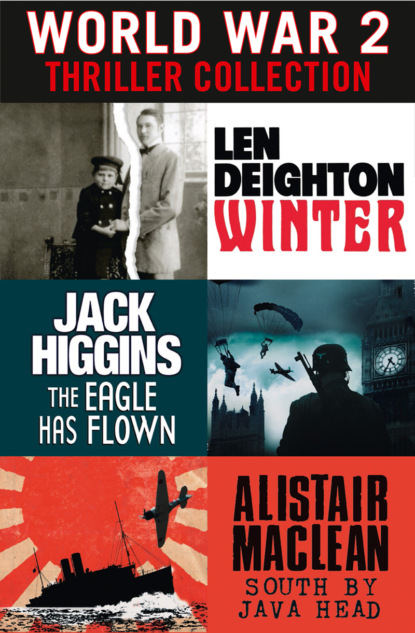

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The Valhalla gave the boys a unique chance to be away from any kind of supervision. They took little advantage of this cherished freedom except to laze and, more important, to talk and argue in that spirited and curiously intimate way that children only do when no adults are within earshot.

‘You’ll change your mind again before you are fourteen,’ Peter told his ten-year-old brother with all the mature authority of a fourteen-year-old. ‘I wouldn’t go to cadet school; I’d hate it. I’m going to be an explorer.’ He trailed his hand in the water. The wind had been swinging round for the last hour or more, so that Peter had had to adjust the sail constantly. Now the boat was moving fast through the choppy water of the bight. The sun was a white disc seen fitfully behind hazy clouds. There was little heat in the sun. Visitors did not come to this northern coastline to bask in the sunshine; it was a brisk climate, for active holidaymakers.

The boys were dressed in yellow oilskins and floppy hats, just like the real sailors who sailed the big ships out of Kiel, along the coast from here. The younger boy, Paul, was crouched in the stern, hugging his knees. His hair was long and had become even more blond as he got older. People had said that his hair would darken, but adults had been wrong about that as about most other vital things he’d wanted to know. He said, ‘You’re good at mathematics. You’d have to be good at mathematics for exploring, wouldn’t you?’

‘Yes,’ said Peter, who’d recently come top in mathematics.

‘I’m no good at anything except sport: hockey, I’m good at hockey. Papa says the cadet school will be best for me. I’ll never be any good at mathematics.’

‘No, you won’t,’ said Peter.

Paul looked at his elder brother. It was a simple statement of fact: Paul was no good at mathematics and never would be. Adults all said that he was young and that soon he’d understand such scholastic subjects. The adults perhaps believed it, but it wasn’t true, and Paul preferred to hear his brother’s more brutal answer. ‘And then after cadet school I’ll be a soldier and wear a uniform like Georg.’ Georg was a young soldier who was walking out with one of the housemaids in Berlin.

‘Not like Georg,’ said Peter. ‘You’ll be an officer and ride a horse and parade down Unter den Linden and salute the Kaiser on his birthday.’

‘Will I?’ said Pauli. It didn’t sound at all bad.

‘And go off and fight the Russians,’ said Peter.

‘I wouldn’t like that so much,’ said Paul. ‘It would mean leaving Mama and Papa.’ He loved his parents as only a ten-year-old can. His father was the person he envied, respected and admired more than anyone in the whole world; and Mama was the one he ran to when Papa scolded him.

‘There’s more wind now,’ said Peter. The sail was drumming and there were white crests on the waves. ‘Take the helm while I fix the sail.’

Big storm clouds moved across the hazy sun. It went dark quite suddenly, so that the sky was almost black, with only a shining golden rim on the most distant of the clouds, and a bright shimmer of water along the horizon. ‘Is it a storm?’ said Paul. Two years ago they’d sailed through one of the sudden summer squalls for which this coast was noted. But that was in a bigger boat and with a skilful yachtsman in charge.

‘It’s nothing,’ said Peter. But as he said it, bigger waves struck the hull with enough force to make loud thumping noises and toss the small boat from side to side.

‘Pull the rudder round,’ said Peter.

The little blond boy responded manfully, heaving on the tiller to bring the boat head on to the waves. ‘But we’re heading in the wrong direction now. We’re heading out to sea,’ said Paul. The waves were getting bigger and bigger, and when he looked back towards Omi’s house the coast was so far away that it was lost in the haze of rain. Paul was frightened. He watched his brother struggling with the sail. ‘Do you want me to help?’

‘Stay at the tiller,’ called Peter loudly. He’d heard the note of fear in his young brother’s voice. He let go a rope for long enough to wave to encourage him. It was then that one of those freak waves that the sea keeps for such moments of carelessness hit the boat. The deck was slippery and Peter’s wet shoes provided no grip upon the varnished woodwork. There was a yell and then Pauli saw the sea swaddle his brother into a dirty-green blanket of water and bundle him away into the fast-moving currents.

Peter had never been a strong swimmer and hit by half a ton of icy-cold sea water, the breath knocked out of his lungs, he opened his mouth. Instead of the air he needed, he swallowed cold salty water, and felt his stomach retch at the taste of it. Sucked down into the cold water, he somersaulted through a dim green world until he no longer knew which way was up.

‘Peter! Peter!’ There was nothing but milky-looking waves and mist, and the boat raced on before the gusting wind. Pauli jumped to his feet to pull the sail down, and before he could move aside the tiller was torn from his hands strongly enough to whack him across the leg, so that he cried out with the pain of it. He couldn’t reef in the sail, he knew he couldn’t: it was something his brother always attended to. ‘Peter! Please, God, help Peter.’

Some distance away from the boat, Peter came to the surface, spluttering and desperately flailing his arms so that he got no support from the water. Still encumbered in his yellow oilskin jacket, he slid down again into the hateful green, chilly realm from which he’d just fought his way. He closed his mouth only just in time to avoid a second lungful of sea water, and let the water close over him, twisting his arms in a futile attempt to claw his way back to the surface. The green water darkened and went black.

When Peter saw daylight again, the waves were still high enough to smash across his head. Like leaden pillows, they beat him senseless and scattered a million grey spumy feathers across the heaving sea. He could see no farther than the next wave and hear nothing but the roar of the wind and the crash of water. It seemed like hours since he’d been washed overboard, and – although it was no more than three minutes – he was physically unable to save himself. His small body had already lost heat, till his feet were numb and his fingers stiffening. Besides the temperature drop, his body was bruised and battered by the waves, and his stomach was retching and revolting at the intake of cold salty water.

There was no sign of the Valhalla, but even had it been close there would have been little chance of Peter’s catching sight of it through the grey-green waves and the white, rainy mist that swirled above them.

No one ever discovered why little Pauli jumped off the stern of the Valhalla and into the raging water that frightened him so much. Many years later explanations were offered: his wife said it was a desperate wish to destroy himself; a prison psychologist interpreted it as some sort of baptismal desire; and Peter – who heard Pauli talk about it in his sleep – said it was straightforward heroism and in keeping with Pauli’s desire to be a soldier. Pauli himself said it was fear that drove him from the safety of the boat into the water; he felt safer with his brother in the sea than alone on the boat. But that was typical of Pauli, who tried to make a joke out of everything.

Little Pauli was a strong swimmer and unlike his brother, he was able to divest himself of the oilskin and prepare himself for both the coldness and the strength of the currents into which he plunged. But, like his brother, he was soon disoriented, and couldn’t see past the big waves that washed over him constantly. He swam – or, rather, flailed the heaving ocean top – hoping he was heading back towards the coast. Above him the clouds raced overhead at a speed that made him dizzy.

The squall kept moving. It passed over them as quickly as it had come, moving out towards Bornholm and Sweden’s southern coast. The racing clouds parted enough to let sunlight flicker across the waves, and then Pauli caught sight of the yellow bundle that was Peter.

Had Peter been completely conscious, it’s unlikely that the smaller child would have been able to support his brother. All drowning animals panic; they fight and thrash and often kill anything that comes to save them. But Peter was long past that stage. He’d given up trying to survive, and now the cold water had produced in him that drowsiness that is the merciful prelude to exposure and death.

Peter’s yellow oilskin had kept him afloat. Air was trapped in the back of it, and this had pulled him to the surface when all his will to float had gone. They floated together, Pauli’s arm hooked round his brother’s neck, the pose of an attacker rather than a saviour, and the other arm trying to move them along. The coast was a long way away. Pauli glimpsed it now and again between the waves. There was no chance of swimming that far, even without a comatose brother to support.

They were floating there for a long time before anything came into sight. It was a boy at the oars of a brightly painted rowboat, trying to get to the Valhalla, who saw first a yellow floppy hat in the water, and then the children, too. The oarsman was little more than a child himself, but he pulled the two children out of the water and into his boat with the easy skill that had come from doing the same thing with his big black mongrel dog, which now sat in the front of the boat, watching the rescue.

The youth who’d rescued them was a typical village child: hair cut close to the scalp to avoid lice and nits; teeth uneven, broken and missing; strong arms and heavy shoulders, his skin darkened by the outdoors. Only his height and broad chest distinguished him from the other village youths, that and the ability to read well. To what extent it was his height, and to what extent his literacy, that gave him his air of superiority was debated. But there was a strength within him that was apparent to all, a drive that the priest – in a moment of weakness – had once described as ‘demoniacal’.

The seventeen-year-old Fritz Esser looked at the two half-drowned children huddled together in the bottom of his boat and – despite the pitiful retching of Peter and the shivers that convulsed Pauli’s whole body – decided they were not close to death. He rowed out to where the poor old Valhalla had settled low into the water, its torn sail trailing overboard and its rudder carried away. ‘It will not last long,’ he said, ‘it’s holed.’ Pauli managed to peer over the edge of the rowboat to see what was left of their lovely Valhalla, but Peter was past caring. Esser, aided by the black mongrel, which ran up and down the boat and barked, tried to get the Valhalla in tow, but his line was not long enough, and finally he decided to get the two survivors back to dry land.

He put them in an old boat shed on the beach. It was a dark, smelly place; the only daylight came through the chinks in its ill-fitting boards. Inside there was space enough for three rowboats, but it was evident that only one boat was ever stored here, for most of the interior was littered with rubbish. There were furry pieces of animal hide stretched on racks to dry. There was flotsam, too: a life preserver lettered ‘Germania – Kiel’, torn pieces of sails and old sacks, broken oars and broken crates and barrels of various sizes arranged like seats around a small pot-bellied iron stove.

Esser wrapped sacking round the boys and poked inside the stove until the sparks began to fly, then tossed some small pieces of driftwood into it and slammed it shut with a loud clang. The necessity of closing the stove became apparent as smoke from the damp wood issued out of the broken chimney. It was only after the fire was going that the boy spoke to them. ‘You’re the Berlin kids, aren’t you? You’re from the big house where old Schuster does the garden. Old Frau Winter. Are you her grandchildren?’ He didn’t wait to hear their reply; he seldom asked real questions, they found out soon enough. ‘You come here with your mother, and the flunkeys, and your father comes sometimes, always in some big new automobile.’

Peter and Pauli were huddled together under some sacking that smelled of salt and decaying fish. As the stove flickered into life, and the air warmed, the hut became more and more foul. But the children didn’t notice the odour of old fish or the stink of the tanned hides. They clung together, cold, wet and exhausted; Pauli was looking at the flames in the tiny grate, but Peter’s eyes were tightly closed as he listened to Fritz Esser’s hard and roughly accented voice.

‘I hate the rich,’ Esser said. ‘But soon we’ll break the bonds of slavery.’

‘How will you do that?’ asked Pauli, who, typically, was recovering quickly from his ordeal. It sounded interesting, like something from his 101 Magic Tricks a Bright Boy Can Do.

Esser wracked his brains to remember what the speaker from the German Social Democratic Party had actually said. ‘Capitalism will perish just as the dinosaurs perished, collapsing under the weight of its own contradictions. Then the working masses will usher in the golden age of socialism.’

Half drowned he might be, but Pauli could perceive the majesty of that pronouncement. ‘Is that how the dinosaurs perished?’ he asked.

‘You can scoff,’ said Esser. ‘We’re used to the sneers of the ruling classes. But when blood is flowing in the gutters, the laughing will stop.’

Pauli had not intended to scoff but decided against saying so while the role of scoffer commanded such a measure of Esser’s respect.

‘We have a million members,’ Esser continued. He spat at the stove and the spittle exploded in steam. ‘We’re the largest political party in the world. Soon they’ll start to arm the workers and we’ll fight to get a proper Marxist government.’

‘Where did you find out all this?’ Pauli asked. It sounded frightening but the strange boy was not unfriendly: just superior. His chin was dimpled and his brown eyes deep and intense.

‘I go to meetings with my father. He’s been a member of the SPD for nearly ten years. Last year Karl Liebknecht came here to give a speech. Liebknecht understands that blood must flow. My father says Liebknecht is a dangerous man, but my uncle says Liebknecht will lead the workers to victory.’

‘Did your father tell you about the dinosaurs and the blood in the streets and all that?’ asked Pauli.

‘No. He’s soft,’ said Esser. He stoked the fire to make it flare. ‘My father still believes in historical evolution. He believes that soon we’ll have enough deputies in the Reichstag to challenge the Kaiser’s power. If Germany had a proper parliamentary democracy, we’d already be running the country.’

Pauli looked at his saviour with new respect. It would be just as well to remain friends with a boy who was so near to running the country. Peter had opened his eyes. He had not so far joined the conversation, but it was Peter who, having studied Fritz Esser, now identified him. ‘You’re the son of the pig man, aren’t you?’

‘Yes, what of it?’ said Fritz Esser defensively.

‘Nothing,’ said Peter. ‘I just recognized you, that’s all.’ Peter coughed and was almost sick. The salt water was still nauseating him, and his skin was green and clammy to the touch, as Pauli found when he hugged his brother protectively.

For Pauli and Peter – and for many other local children – the pig man was a figure of rumour and awful speculation. A small thickset figure with muscular limbs and scarred hands, he was not unlike some of the more fearful illustrations in their books of so-called fairy stories. The ‘pig man’ wore long sharp knives on his belt and went from village to village slaughtering pigs for owners too squeamish, or too inexperienced with a knife, to kill their pigs for themselves. He was to be seen sometimes down by the pond engaged on the lengthy and laborious task of washing the entrails and salting them for sausage making. So this was the son of the pig man. This was a boy who called the pig man ‘soft’.

In an unexpected spontaneous gesture of appreciation, Pauli said goodbye to Fritz Esser with a hug. Forever after, Pauli regarded Fritz Esser as the one who’d saved his life. But Peter’s goodbye was more restrained, his thanks less effusive. For Peter had already decided that little Pauli was his one and only saviour. These varying attitudes that the two boys had to the traumatic events of that terrible day were to affect their entire lives. And the life of Fritz Esser, too.

It was the pig man himself who took the boys home. Still wrapped in the fusty, stinking old sacks that gave so little protection from the remorseless Baltic wind, they rode on the back of his home-made cart drawn by his weary horse. It was more than seven kilometres along the coast road, which was in fact only a deeply rutted cart track. The smell of rancid fish and pork turned their stomachs and they were jolted over every rut, bump, and pothole all the way. When they got to Omi’s, the pig man and his son were given a bright new twenty-mark gold coin and sent away with muted thanks.