По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

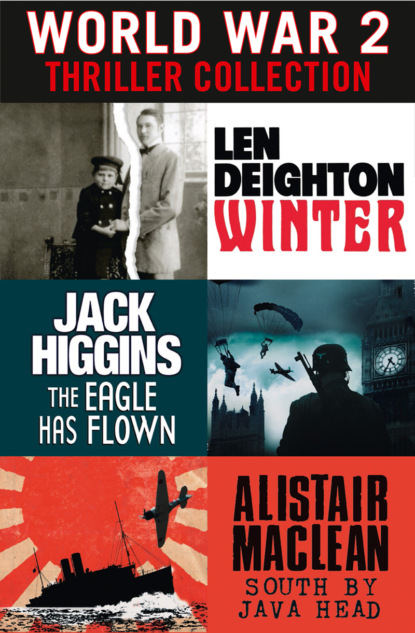

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Harald Winter realized that he’d gone too far. He retracted a little. ‘I didn’t mean your brother, I meant the Engländer.’

‘No one was making sketches, Harry, and the field glasses belonged to Glenn.’

‘Piper is obviously a spy,’ said Winter. He had never really liked the English, and this fellow Piper, with his absurdly exaggerated good manners and the attention he gave to Veronica, was a prime example of the effete English upper class.

‘You sound like a character in those silly books the children read. If the ships are secret, why are they anchored here for everyone to see? And if you are convinced that Mr Piper is a spy, why bring him here?’

‘It’s better that he be someplace where the authorities can keep an eye on him,’ said Winter.

‘You didn’t repeat these suspicions to the people at Fleet Headquarters?’

‘I felt it was my duty.’ He put his glass down with more force than was necessary.

‘Harry, how could you! Mr Piper is our guest. To report him as a spy is…’

‘Ungentlemanly?’ asked Harry sarcastically. Nervously he smoothed his already well-brushed hair. A German wife would know better than to argue about such things.

‘No gentleman would do it, Harry,’ she told him. ‘No English gentleman would do it, and neither would a member of the Prussian Officer Corps. The officers to whom you reported your suspicions of Mr Piper will not see it as something to your credit, Harry.’ It was the first time she’d confronted him with such direct imputations. Harry’s already pale face became white with anger.

‘Damnit, Veronica. The fellow is sent to South Africa without any army rank. He learns to speak Afrikaans and wanders around anywhere that trouble arises. Then the fighting ends and, when you’d think Piper’s expertise is most needed, the British give him a year’s leave and he decides to go and look at zeppelins. But before that he turns up in Kiel, studying the most modern units of the Kaiser’s battle fleet through powerful field glasses.’

‘Must you Germans always be so suspicious?’ she said bitterly. ‘It was you who suggested bringing him to Kiel. You knew the Fleet would be here for the summer exercises – you told me that yourself. Then you report him for spying. Have you taken leave of your senses, Harry? Or are you just trying to find some perverse way to show these naval people how patriotic you can be?’

Her accusation hit him and took effect. His voice was icy cold, like his eyes. ‘If that’s the way you feel about us Germans, perhaps you’d be happier among your own people.’

‘Perhaps I would, Harry. Perhaps I would.’ She rang the bell for her bath to be run. She would be pleased to get back to her mother-in-law’s house. She didn’t like hotels.

Those final summer days at Travemünde marked a change in the children’s lives. They became both closer together and further apart. They were closer because both children knew that Pauli’s desperate leap overboard had saved his brother’s life. Both carried that certain knowledge with them always, and although it was seldom, if ever, referred to even obliquely, it influenced both of their lives.

They became further apart, too, for that summer marked the time when their carefree childhood really ended and they both, in different ways, faced the prospect of becoming men. Pauli, genial and anxious to please, did not relish the prospect of going to cadet school and becoming a member of the Prussian Officer Corps, and yet he accepted it, as he accepted everything his parents proposed, as the best possible course for someone of his rather limited abilities.

Peter’s ambition to be an explorer was, like so many of Peter’s ambitions, a way of describing his desire for freedom and independence. Peter was strong and respected strength, and his narrow escape from drowning made him see that strength came not only from intellect or muscles: strength could come from being in the right place at the right time. Sometimes strength could come from loving someone enough to jump into the sea. Peter had always considered his little brother weak, but now he wasn’t so sure.

The last two days at the house near Travemünde were filled with promises and farewells: false promises but sincere farewells. Glenn and his English friend were the first to go. When would the boys come and see Glenn in New York? Soon, very soon.

Then Peter and Paul went off to find Fritz Esser. He was in his boat shed, chopping wood and bundling it for kindling. He said he was sorry that the Valhalla had never been found again. Perhaps it would turn up. Wrecks along this coast reappeared as flotsam on the beaches after the autumn storms. ‘See you next year,’ the boys told him.

‘I won’t be here next year. My papers will come for the army, but I won’t go. I’ll be on the run.’

‘Where will you hide?’ asked Pauli. They had both come to admire the surprising Fritz Esser, but little Pauli hero-worshipped him.

‘People will shelter me,’ said Esser confidently. ‘Liebknecht says the Party will help.’

In the corner of the old hut Peter spied splinters of beautifully finished white hull, just like that of the Valhalla, but he didn’t inspect them closely. Sometimes it is better not to know.

Along the beach they saw the pig man. He grinned and waved a knife at them: they waved back to him and fled.

The boys said goodbye to Omi, too. They heard their father whisper to Mama that by next year Omi might no longer be here. They kissed Omi goodbye and promised to see her next year.

Veronica went up to the little turret room and spent a few minutes alone there. She would never see the Englishman again: she knew that now. She could never go away without the children, and yet she could not bring herself to take them away from her husband.

1914

War with Russia

Despite all his previous misgivings, Paul was not unhappy at his military school. In fact he rather enjoyed it. He enjoyed the unvarying routine, and he appreciated the way everyone accepted his scholastic limitations. It was all very strange, of course. Most of the other boys had come from Kadettenvoranstalten – the military preparatory schools – and they were used to the army routines and the shouting and marching and the uniforms that had to be so clean and perfect. Cleanliness had never been one of Paul’s priorities, but luckily a boy named Alex Horner, who’d come from the military prep school at Potsdam, helped the fourteen-year-old through those difficult early days of April when they first arrived.

Nothing at Gross-Lichterfelde was quite as he’d imagined it. He’d expected to be trained as a soldier, but his daily routine was not so different from that of any other German high school except that the teachers wore uniforms and he was expected to march and drill each afternoon. He’d hoped to be taught to shoot, but so far he’d not even seen a gun.

His father had told him that the Emperor had to approve each and every entrant to this, the Prussian army’s only cadet school, and that only the sons of aristocrats, army officers and heroic lower ranks could be admitted. The truth was somewhat different: most of the cadets were, like Paul, the sons of successful businessmen or of doctors, lawyers, bureaucrats and even wealthy farmers. Only a few of the boys had aristocratic families and most of these were the second or third sons of landowners whose estates would go to their elder brothers.

Alex Horner was typical of these disappointed younger sons. His father owned four big farms in East Prussia and had served only a couple of years in the army. Alex owed his place at Lichterfelde to the efforts of an uncle who was a colonel in the War Office.

It was Alex who always pulled Paul out of bed when reveille was sounded at six o’clock and got him off to the washroom before the cadet NCO came round to check the beds. A quick wash and then buttons. It was Alex who showed him how to use a button stick so that no metal polish marked his dark-blue tunic: a sleepy boy at the other end of the room who once tried polishing his buttons last thing at night instead of before breakfast discovered how quickly brass dulled, and served a day under arrest. Thanks to Alex, Paul was usually one of the first outside ready to be marched off to the standard Lichterfelde breakfast of soup and bread and butter. But the most important reason that Pauli had for liking Alex Horner was that Alex had seen Pauli crying his heart out on the night he first arrived, and Alex had never told a living soul.

Marching back from breakfast along the edge of the parade ground that morning in July, Paul remembered April 1, the day he’d arrived. That was over three months ago; it seemed like years. His father had insisted that Mama shouldn’t come, and Paul appreciated his father’s wisdom. He was quite conspicuous enough in the big yellow Italian motorcar with Hauser at the wheel. The Winters had lost two chauffeurs, who went to drive Berlin motor buses, so Hauser, the valet, had now learned to drive the car, and he’d promised to teach the boys, too, as soon as they were tall enough to reach the foot pedals.

Paul could look back now and smile, but that very first day at the Königlich Preussische Corps des Cadets at Lichterfelde – or what he’d now learned to call Zentralanstalt – had come as a shock. Although the band was playing, it didn’t offset the fuss the parents were making with their tearful mothers and odd-looking fathers. The poor boys knew they would be teased mercilessly about every aspect of their parents, and everything they did and said within the hearing of their fellow recruits.

Now it was summer, almost eight o’clock, and the sun was very low and blood red in an orange sky. Soon it would be hot, but the morning was cool, and a march to breakfast and back again was almost a pleasure. Crunch, crunch, crunch. Paul had learned to take pride in the precision of their marching. For the boys with years of cadet training already behind them it was all easy, but Paul had had to learn, and he’d learned well enough to be commended and allowed to shout orders to the cadets on one momentous occasion. Halt! There was much stamping of boots while the cadet NCO saluted the lieutenants, and the lieutenants saluted the Studiendirektor. Then, file by file, all two hundred cadets marched into the chapel for morning service.

‘Something has happened,’ whispered Alex. The chapel was gloomy; the only light came through the small stained-glass windows.

‘War?’ said Paul. The darkness and the low, vibrant chords of the organ provided a chance for furtive conversations. There was a clatter of hobnailed boots when one of the seniors stumbled as the back row was filled. Then the doors were closed with a resonant thump.

The boy next to him was a senior – one of the Obertertia, the boys permitted to go to rifle shooting in the afternoons. ‘The Serbs have replied to the Austrian ultimatum.’

‘Everyone knows that,’ whispered a boy behind them, ‘but will the wretched Austrians fight?’

‘Quiet!’ called a cadet NCO. ‘Horner and Winter, report to me after Latin class.’

Paul stiffened and looked down at his hymnbook. It was always like that: the junior year got punished and the senior boys escaped. Was it because their sins were overlooked, or had they become more skilled at talking without moving their lips? Alex kicked Paul in the ankle; Paul glanced at him and grinned. He hoped it would mean nothing worse than being put on half lunch ration – the other boys always helped out and the last time he’d eaten even better on punishment than he normally did – but if he got a three-hour arrest this afternoon he’d be late home, and then he’d have Father to answer to. Paul hated to be in disfavour with his father. His brother, Peter, had always been able to shrug off those fierce paternal admonitions but Paul wanted his father to admire him. He wanted that more than anything in the whole world. And it was Friday: this weekend he’d arranged for Alex Horner to come home with him, and a detention now would mess everything up.

‘Hymn number 103,’ said the chaplain mournfully, but no more mournfully than usual.

Paul and Alex escaped with no more than a fierce reprimand. Luckily their persecutor wasn’t one of their own NCOs but a senior boy who didn’t want to miss his riding lesson. Normally at 4:30 p.m. – after doing two hours of prep – there was drill on the barracks square, but at noon this day the boys were told that they were free until dinner, and that those with weekend passes could go home. It was another sign that something strange was in the air.

And as Alex and Paul went to their train at the Lichterfelde railway station they noticed that civilians deferred to them in a way that was unusual. ‘After you young officers,’ said a well-dressed businessman at the door of the first-class compartment. There was an element of mockery in this politeness, and yet it was not entirely mockery. The ticket inspector touched his hat in salute to them. He’d never done that before.

The boys did not read. They sat erect, conscious of their uniforms, styled like those of the post-1843 Prussian army, rather than the new field-grey ones. Military cap, white gloves, blue tunic, poppy-red cuffs and collar with the double gold braid that marked Lichterfelde cadets, and on the black leather belt a real bayonet.

In the other corner of the compartment, the man who’d ushered them inside sat reading a copy of the daily paper. The big black headline in Gothic type said ‘Russia mobilizes.’

From the Potsdamer railway station they walked through the centre of Berlin: past the big expensive shops of Leipziger Strasse, and then along Friedrichstrasse. Everywhere they saw groups of people standing around as if waiting for something to happen. There were more women on the streets nowadays – shopping, strolling, exercising dogs; the shorter skirts enabled women to be out and about in a way they never had before. The narrow Friedrichstrasse was always busy, of course; here were offices, shops, cafés and clubs, so that it never stopped, night or day. But today it seemed different, and even the wide Unter den Linden was filled with aimless people. At the intersection of the two streets – one of the most popular spots in all Berlin – was the boys’ destination: the Victoria Café and the best ice cream in town.

They got a table outside on the pavement and watched the traffic and the restless crowds. A No. 4 motor bus went past; on its open top deck were half a dozen soldiers. They were flushed of face and singing boisterously. The bus was heading towards the Friedrichstrasse railway station, where there were always military policemen. Alex predicted that they would be in cells within half an hour, and there was little chance that he would be wrong.

Everything was bright green, the lime trees were in full leaf, and the birds were not frightened of the noise, not even of the big new motor buses. Only when the band marched past did the birds fly away. Alex said the band was that of the 3. Garde-Regiment zu Fuss marching back to its barracks at Skalitzer Strasse. They wore white parade trousers and blue tunics and gleaming helmets, and the music sounded fine. Behind them was a company of infantry in field grey. They looked tired and dusty, as if they’d been on a long route march, but when they got to the corner of Friedrichstrasse there were some cheers from civilians standing there, and the soldiers seemed to stiffen up and smile.