По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

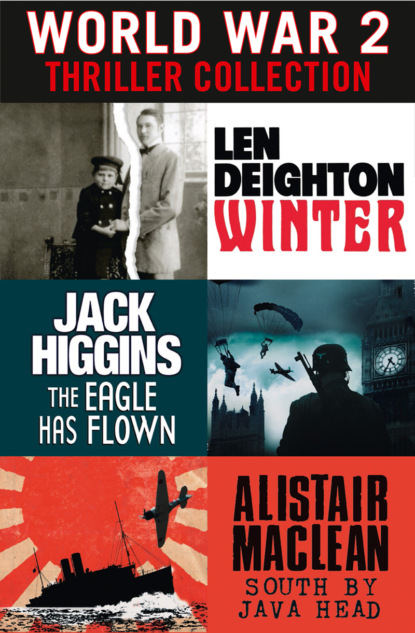

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘It’s called a swastika. Many of the Freikorps units wear it to distinguish us from the regular army.’

‘Be very careful, Pauli. Remember what happened to your brother.’

Pauli did remember. Peter had been beaten up just because of the ‘imperial insignia’ on his officer’s uniform. Many army and navy officers had been similarly beaten – and several murdered – by jeering and catcalling thugs who were determined to blame the officer class for the war and its outcome.

‘I wear a private’s greatcoat and no badges,’ said Pauli.

‘But you have an officer’s sidearm,’ said his father.

‘And I’ll use it, too,’ said Pauli. ‘I’d be grateful for a chance to pick off a few of the bastards who tried to kill Peter.’

‘Don’t say goodbye to your mother: she’ll only worry until you telephone.’

‘I’ll telephone if I can, but the telephone lines are sometimes cut.’

‘Take care of yourself, Pauli,’ said his father. ‘Those mutinous swine are holding the Chancellor to ransom…. My God, who could have guessed it would come to this? The Chancellor held prisoner by Marxist hooligans.’ They embraced, and as he grasped him in his arms Pauli was struck by the slight, frail frame of his father. Although not yet fifty years old, Winter had grown old and tired and apprehensive. Perhaps it was only temporary, but it was a sad transformation in a man the boys always remembered as dynamic and rather frightening.

Harald Winter regarded his son with equal sorrow. The war had made Pauli into a ruffian. He was brusque and dismissive of all the values that Harald Winter revered. This new Pauli who’d come back from the war was someone his father found difficult to cope with. As much as he’d disliked the dependence that Pauli had demonstrated as a child, he preferred that to the new rough-spoken man he’d become. In other words, like many fathers, Harald Winter hated to see that his son had grown up.

Pauli took the S-Bahn to Alexanderplatz. The trains were running normally but as Pauli walked towards the palace he kept a wary eye open for marauding bands of troublemakers. He saw a small procession of factory workers – women, too – going over the Schlossbrücke. They were not armed but they carried red banners and chanted slogans, so he remained in the shadows until they passed. It was as well to be cautious. Schinkel’s beautiful little guardroom – designed like a Greek temple – was brightly lit and he could see soldiers inside, some of them huddled in blankets on the stone floor. Were they loyal soldiers assigned to duty by the High Command, or Bolshevik renegades? There was no way to know. He hurried past.

The Royal Palace, or what was usually called just the Schloss, was lit only by light from the cathedral across the road, but against the darkening sky he could see the red blanket that mutinous sailors had hoisted up. The palace had had no official residents ever since the Kaiser abdicated and ran away to Holland. It was at present the home of about three thousand bellicose revolutionary sailors of the self-styled ‘People’s Naval Division’ who were now holding the head of government for ransom.

Pauli kept walking along Unter den Linden. The streetcleaners were not in evidence, and in places Pauli had to clamber over piles of snow. Only the streetcar tracks had been systematically cleared of it. Despite the occasional sounds of rifle fire – and sometimes even the explosion of a grenade – the shops were open, and some taxicabs, buses and streetcars were still running. But the shortage of fuel meant that there were more horses: ancient Droschken with half-starved animals plodded through the snow. There were a few shoppers hurrying home past street peddlers selling crudely made paper Christmas decorations and hot chestnuts.

Pauli crossed the road to avoid the crowd milling around the gates of the Russian Embassy. Since April 1918 the Imperial Russian Embassy had been called the Soviet Embassy. At the 1918 party conference, Lenin had told the delegates that ‘…we shall go under without the German revolution.’ And in response the new staff, of no fewer than three hundred people, had been frantically circulating Bolshevik agitators, ready cash and crate-loads of revolutionary literature throughout Germany. The new ambassador – a wealthy Jewish philanthropist from the Crimea – had had hoisted across the embassy’s façade a huge red banner that urged ‘Workers of all countries, unite!’ Soon afterwards he’d been deported back to Russia, but the banner remained.

Guarding the Interior Ministry were three men with rifles slung over their shoulders. Round the corner was a truck with more armed men, their shabby, makeshift uniforms and red armbands identified them as members of an irregular band recruited by the new police chief – Emil Eichhorn – a radical of the extreme left. On the corner of Wilhelmstrasse were some women, one of them weeping uncontrollably. They were on their way back from Dorotheen Strasse, where the army’s casualty lists were still being displayed, with new names every day. The fighting had ended, but corpses were still being identified. Pauli walked past them and crossed back across the road to the Adlon Hotel.

He checked his helmet, overcoat and pistol belt at the cloakroom. The elderly attendant showed no surprise. He placed the gun and helmet on a shelf with silk hats and gave Pauli a small yellow ticket. Pauli went into the bar. There was a crowd in here, but the heating was not working, and some customers had their overcoats on. He had arranged to meet Alex Horner here, and true to form, Alex was sitting near the door with a bottle of wine in an ice bucket at his elbow. An extra glass was in place. From the dining room next door came the high-spirited music of a gypsy band.

‘How goes the army command?’ said Pauli. He sat down and waited for the waiter to pour his wine.

‘Excellent!’ said Alex. ‘And how are things at home?’ Alex was not in uniform. He was wearing a smart new grey flannel suit, white shirt and dark tie, but no one in the bar – or in Berlin, for that matter – could possibly have mistaken him for anything but a Prussian of the Officers Corps.

‘Peter is still moaning. Papa won’t leave the house and says it’s on account of the influenza epidemic. Mama has become something of a tyrant but she still manages to serve meat, even for lunch: sauerbraten today. I had two helpings.’

‘Your mother is a woman of infinite resource,’ said Alex.

Alex had secured an excellent job – or rather, his influential relative in the War Department had secured it for him. After the failure of the big German offensive of 1918, he was sent to Supreme Headquarters in Spa, Belgium, and appointed an aide de camp to General Schammer, the military governor of Berlin.

The present military governor was a rather disreputable civilian but that didn’t prevent Alex from lording it over his old friend, for there was a great difference between duties on behalf of the headquarters of the Imperial German Army and being with the Freikorps, an ad hoc assembly of enthusiastic volunteers consisting almost entirely of men the army had no place for.

Alex liked to give his friend insightful anecdotes about life among the generals. For a few minutes Alex entertained him with stories about the new commander of the German Army. ‘General Groener is a good sort,’ said Alex. ‘He’s highly intelligent and not at all stuffy.’

‘He’s a Schwab,’ said Pauli before sipping some wine. ‘Get rid of all these damned Prussians, I say.’ It was a Riesling from Alsace, just cold enough and it tasted delicious. Goodness knows when he’d taste its like again: under the terms of the armistice Alsace was now a part of France once more.

Alex grinned. Although Pauli was born in Vienna to an American mother, his upbringing was hardly less Prussian than his friend’s, but there was a running joke that Alex was a Prussian of the most inflexible old-fashioned kind and Pauli was the oppressed Southerner. The friendship between the two boys was based on a long time together and mutual respect. And yet, right from the time they’d first met at Lichterfelde, Pauli was the admirer and Alex, by common consent, was granted an edge of seniority. The admiration that Pauli had always shown for his elder brother Peter was reflected in his respect for Alex. And, typically, Alex responded to this faith that Pauli showed by revealing to him his most treasured secret. Alex said, ‘Although the Chancellor is being held prisoner in his office there’s a secret telephone line from the Chancellery to the army. Chancellor Ebert has asked the army for help.’

‘Good God!’ said Pauli. Everyone believed that the mutinying sailors had cut all the lines from the Chancellery and that Ebert – the new socialist head of government – was being held incommunicado.

‘That’s just between the two of us,’ said Alex. ‘It’s a closely guarded secret, not to be passed on even to your father.’

‘Just as you say, Alex. But it changes things, doesn’t it?’

‘Yes, and the army will do what has to be done,’ said Alex enigmatically. ‘Those mutinous pigs will find out what it means tomorrow.’

‘Christmas Eve?’ said Pauli. ‘Why?’

‘Are you in a hurry?’ said Alex languidly.

‘I’ve got all the time you need,’ said Pauli, sipping some more wine and leaning forward to hear what Alex had to tell.

‘It all began on November 9,’ said Alex.

‘Everything did,’ said Pauli.

That much was true: everything began on November 9, 1918. The army’s commanders – too arrogant to face the consequences of their own defeat – had sent some unfortunate civilians through the wire of no-man’s-land to seek an armistice from the Allies, as the Turks and Austrians had already done. During that Saturday, the Imperial German Army ceased to exist as a unified fighting force. Red flags were flying all over the land as soldiers’ committees took control. Alex Horner, on one of his regular visits to Supreme Headquarters from Berlin, was shown the reports. It was amazing: the army’s command structure collapsed like a deck of cards. ‘Riots in Magdeburg’; then, early in the afternoon, ‘7th Army Corps Reserve District rioting threatened’. Halle and Leipzig were declared ‘red’ by 5:00 p.m., and soon afterwards Düsseldorf, Halstein, Osnabrück and Lauenburg went, too. So did Magdeburg, Stuttgart, Oldenburg, Brunswick, and Cologne. By this time the soldiers at Supreme HQ had stopped saluting the officers, and some of the offices were deserted. At 1900 hours, news came that the general officer commanding 18th Army Corps Reserve at Frankfurt was ‘deposed’. It was all over. By early evening Kaiser Wilhelm, German Emperor and ‘All-highest Warlord’, was sitting in the dining car of his private train, waiting for it to leave the siding and start the journey that would take him to exile in Holland.

In Berlin the socialist Cabinet, which had been created without any legal transfer of power, could not contain the disorder. They ordered the army to rip up sections of railway line and so interrupt the trainloads of mutinous soldiers and sailors that were arriving in the capital in ever-increasing numbers. When Alex arrived at the Lehrter station, in a train that had taken two and a half days to reach Berlin from Belgium, he was startled to see that army machine-gun teams commanded a field of fire along every platform and the main concourse. Troops were occupying the gas and electricity works, the government buildings on Wilhelmstrasse were all guarded, and there were even armed soldiers outside some of the town’s finest restaurants.

By the time that Leutnant Horner reported to Berlin’s military governor, that governor was a socialist civilian named Otto Wels. The Imperial Army’s Berlin garrison having deserted – and having no more than a handful of civil policemen at his disposal – Wels had put together a force of ex-soldiers and armed civilians. Most of the rifles had been bought from the deserters who, standing alongside the flower girls, were doing a brisk trade at the Potsdamer Platz at two marks per gun. Even the ‘army’s’ trucks had been purchased in this way from the deserters. Wels had given his scratch force the grandiose title of Republikanische Soldaten – the Republican Soldiers’ Army – but they were a motley collection difficult to distinguish from the extreme left Sicherheitswehr that the Police President employed, or from any of the other armed mobs who patrolled the city looking for victims and plunder. Moreover, Wels’s army was infiltrated by many Spartacists and the extreme-left Independents.

It needed only one visit to the military governor’s office to convince Alex Horner that his officer’s uniform was not suitable attire. He bought a suit in a tailor’s shop in Friedrichstrasse – the first ready-made suit he’d ever worn – and went back to work feeling less uneasy. He did notice the way that the carefully positioned beggars watched him as he arrived. There were few beggars to be seen on the streets in these early days of the revolution. Most of the uniformed ex-servicemen who stood outside the department stores and food shops hoping for money still had enough dignity to be offering a tray of bootlaces, matches or candles. Yet these fellows made no pretence of being pedlars, and Alex was convinced that they were spies. Police spies, Bolsheviks, Spartacists and foreigners, too: the city was alive with spies of all shapes and sizes, and of every political colour. Berlin had always been a city of spies and informers, and it probably always would be.

Berlin’s most serious problem was created by the naval mutineers who’d arrived from the Northern naval bases and settled themselves into the Imperial Palace. The fiasco of this People’s Naval Division turned sour when the sailors became more menacing and demanded their ‘Christmas bonus’. The sailors had been under the influence of Karl Liebknecht ever since occupying the Imperial Palace. And it was Liebknecht’s declared intent to bring down the moderate socialist government of Friedrich Ebert – a forty-seven-year-old ex-saddle maker – by anarchy and confusion. Having the sailors demand ever more money was very much to Liebknecht’s taste. If Ebert was frightened by the extortion and paid out the money, the government would demonstrate their weakness. If they moved against the sailors, it would be a sign that they were the sort of treacherous, reactionary, anti-working-class government that Liebknecht said they were. Either way it would make things easier for Liebknecht to seize power and set up his Leninist regime.

It was December 20 when the sailors announced that they’d spent the first 125,000 marks the government had paid them for guarding the Imperial Palace. Now they wanted more money.

Alex Horner was in the anteroom of the Chancellor’s private office when Otto Wels came out with Ebert. It was the first time Alex had seen the Chancellor at such close quarters. He was an imposing figure, broad and muscular, with jet-black hair and a large moustache and small beard. The government had agreed to pay more money, but first the palace must be evacuated and the People’s Naval Division reduced to six hundred men. The money would be paid only after the keys of the emptied palace had been given to Otto Wels.

On the morning of the day on which Alex and Pauli met, Alex had hurried down to the lobby of the Chancellery in response to a phone call from one of the secretaries. A delegation of sailors was being taken to one of the drawing rooms that were situated to the side of the fine Empire vestibule. One sailor was carrying a leather case that he said held the keys of the Imperial Palace. They wanted their money.

‘Herr Horner is one of the military governor’s assistants,’ said the secretary who was dealing with the sailors. He was a sniffy little man with the curt and superior manner that distinguishes career bureaucrats.

The spokesman for the sailors, a tall petty officer with crooked teeth, asked for Alex Horner’s identity papers. Luckily Wels had arranged such formalities as soon as the young officer got back to the revolution-stricken city. Taken to a Reichstag office by an attendant wearing the livery of the old regime, he’d been given a pass by a woman clerk wearing a red armband. It was an inexpertly printed card on stiff red paper. It said that Horner was ‘authorized to maintain order and security in the streets of the city’. Accompanying it was an identity card issued by the ‘Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council’ saying he was ‘trustworthy and free to pass’. Neither document mentioned his military rank, and if the woman issuing the papers to him knew him to be an army officer she gave no sign of it. From the way she handled the office files, it looked as if she was occupying the same desk as she had before the revolution. Most of the workers were doing the same thing that they’d done during the Kaiserzeit without the red bands and banners. For the Berliner, life was simply a matter of exchanging time for money and money for food. Even during the shooting, the buses ran on time and the water and electricity supply continued normally.

Having scrutinized Horner’s papers, the petty officer showed him his card in return. ‘Petty Officer Esser’. How curious that so many of these revolutionary servicemen clung so tightly to the badges and titles and privileges of the old regime.

Esser politely but firmly explained to Horner and the secretary that the political committee of the People’s Naval Division had decided that they’d not deal with Otto Wels, who, although a socialist, was ‘a class enemy’.

‘Then give the keys to Herr Barth,’ suggested Alex. He was grateful that the secretary had not revealed the fact that he was an army officer.

‘Herr Barth is in a meeting and cannot be disturbed.’ The secretary expected them to hand the keys to him and depart without further delay. Despite wearing a small red ribbon in his buttonhole – a sartorial accessory that had been adopted by many middle-class office workers during the previous few days – the man did not hide his impatience and his distaste for the unwashed revolutionaries.

‘Then get him out of the meeting,’ suggested Alex.

The secretary shook his head to show that there could be no question of interrupting the commissioner. Emil Barth was amongst the most radical of the commissioners, but these wretched socialists had quickly adapted to the bureaucracy of Wilhelmstrasse: meetings, meetings, meetings. And the bureaucrats had easily adapted to their new masters.