По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

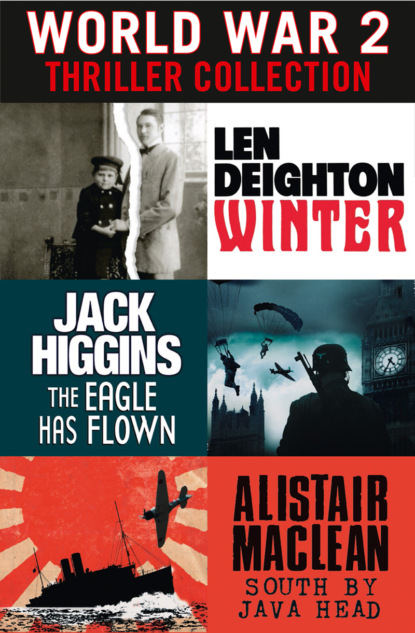

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘They didn’t care that I’d been in a Punishment Battalion, if that’s what you mean. Yes, they made me a Stosstruppführer. There were plenty of vacancies: officers always had to lead their men into the attack. Only young, unmarried men were accepted, and the physical was the strictest I’ve ever had.’

‘I envy you the experience, Pauli. The storm battalions have become a legend. But you were lucky to survive.’

‘You mustn’t believe all the stories you hear, Alex. Storm troops were kept in the rear until they were needed for some special task; even then they took us most of the way by truck. And we had lots of leave, and the food was always the very best available.’

‘You sound nostalgic, Pauli.’

‘Let me explain something to you, Alex. You grew up wanting to be an army officer. But I never wanted to go to cadet school. It was my father’s idea. I loved my father – I still do – but my father has no respect for me; he thinks I’m brainless, and he doesn’t care about anything except brains, especially the sort of brains that know how to make money. My elder brother doesn’t give a damn about Father, but he’s the one my father loves. I realized that I didn’t have the brains that my brother Peter has, so I went to the cadet school the way Papa wanted. Now soldiering is the only trade I know.’

‘Well, now the workers’ and soldiers’ committees are taking over all your father’s factories, it’s ended up making little difference to you.’

‘Papa will find a way; he always does.’

‘But you seemed happy enough at Lichterfelde.’

‘Yes, I came to like it. I’ve always been adaptable: younger brothers have to adapt to what everyone else wants. And I liked the respect that an officer’s uniform got for me. Do you remember, Alex? Members of the Officer Corps were gods. I loved all that, Alex, the bowing and scraping that I got from civilians. I loved being saluted, and the way that people stood aside to let me pass in the street and let me be served first in shops.’

‘I suppose we all did. And yet here we are: me skulking in civilian clothes and you masquerading as a private soldier.’ Pauli looked at his friend. Alex was wearing a grey bowler hat and an old-fashioned Inverness – a loose-fitting grey overcoat with attached shoulder cape. It wasn’t a particularly odd costume amid the curiously garbed people to be seen on the city’s streets, but it was hardly appropriate for a Prussian officer.

Pauli nodded. ‘And I even loved the Kaiser. I loved the idea that someone knew what was best for Germany and what was best for the army and the Officers Corps and what was best for me. And when the war went on and all sorts of riffraff like Brand managed to get commissions, I still didn’t care, because those people weren’t real officers: the Prussian Officer Corps was still a small elite that outsiders couldn’t enter.’ They walked in silence for a few moments while Pauli collected and ordered his thoughts. ‘And then came the Sturmbataillon. It was a world I’d never known. It let me be myself. I wish you’d been with me, Alex.’

‘You said that in one of your letters.’

‘We spoke using “du”, officers and men alike. I called my men by their first names, and often we’d be sitting around talking together with no rank deferentials. Arguing politics, or talking about what kind of Germany we’d have after the war.’

‘And did any of you guess it would be like this?’ Alex whipped his walking stick through the heaped snow.

Pauli snorted. ‘Who could have guessed it would end like this? No one! Who would have guessed that the Kaiser would run away so that Fritz Esser and his friend Liebknecht would be sitting in the Imperial Palace? Who’d guess that a collection of half-baked intellectuals and socialist draft dodgers would be running Germany as a ramshackle republic, and that the Imperial Horse Guards would be answering their call for help?’

‘I thought you were about to tell me that your time with the common man had provided you with a new understanding of the socialists, Pauli.’

‘Socialists are dreamers. The time for dreaming is long past. Our Fatherland is dying, and no one goes to help.’ He kicked the top from a mountain of snow, so that it shattered into a white cloud.

When they got to Friedrichstrasse they had to wait for the traffic before they could cross the road. It was astounding how life went on, seemingly unaffected by the fact that the city was in the throes of revolution. Even while shooting could be heard, the Christmas shoppers crowded the pavements and the motor buses kept going. There was the smoky smell of roasted chestnuts and the sound of American jazz music from one of the nearby clubs. A shop assistant and a chauffeur were loading dozens of coloured parcels into a large car while a fur-coated matron counted them. It was hard to believe that the dull thuds heard earlier that day had been mortar shells exploding, and that right now artillery was on its way to assault the Imperial Palace.

‘Civilians have their own affairs to attend to,’ commented Alex as they crossed the road, dodging a taxicab.

‘Making money, do you mean?’ said Pauli scornfully.

‘You can’t live without it.’

‘There are other, more important things than money, Alex. That’s what I learned with the storm troops, and that’s what many of our Freikorps volunteers believe.’

‘Are they men from your old storm troops?’

‘In my battalion a dozen or so are old comrades. That’s what made me join. If recruiting continues as at present, I’ll have my own company next month.’

Alex Horner chuckled. ‘And all this time I’ve been thinking that you’d become old and cynical, Pauli, While really you are the same fervent optimist and dreamer that I’ve always known.’

‘You can mock me, but…’

‘I’m not mocking you, Pauli. We all feel the same way. Everyone I know and respects feels more or less the way that you do. They all feel frustrated watching this damned government being treated with contempt by every rascal at home, and spat upon by Paris, London and Washington.’

‘But you remain aloof? Or are you just fatalistic?’

‘If the mob wants to be ruled by the Spartacists, then so be it. I’m a professional soldier; I’ll obey lawful commands from the army, just as the Russian army do under Lenin.’

Pauli shook his head. ‘You are too naïve, Alex. Do you really think that Lenin represents the Russian worker? Lenin’s party is a tiny, noisy, violent group that seized power and then slaughtered all the opposition. Now, here in Germany, Ebert’s socialists are in the majority but the Spartacists are already trying some of Lenin’s tricks to get power in Germany. And then heaven help Liebknecht’s opponents. They’ll be put against the wall and shot without trial.’

Behind them they heard the sound of marching men coming down the Linden from the direction of the Tiergarten. In the darkness the soldier’s hobnailed boots were striking sparks from the paving. They were Uhlan Guards. The two young officers watched approvingly as the soldiers wheeled into the entrance to the university. There were few such trained and disciplined units left in the whole of Germany.

As the two men got closer to the Imperial Palace, Unter den Linden became more crowded. There were the usual streetcorner groups of men in makeshift uniforms. Most of them had their rifles slung over the shoulder muzzle-down in what had become the style of all the revolutionaries. But these armed men were outnumbered by sightseers who’d arrived in response to the rumours that were now being spread across the city. They wanted to see how the army was going to tackle the bellicose sailors. Or, as another rumour had it, they wanted to watch the army’s monarchists staging a counter-revolution.

When Alex and Pauli reached the main entrance of the palace, three sentries were there, pale-faced youngsters with soft, sailor hats, and bandoliers crossing their chest. They were warming their hands at a bonfire on the pavement. In the fire could be seen bits of antique furniture, its polish and gilt bubbling and blistering in the flames. They asked the guards for Esser. It took a long time to find him. Alex and Pauli stood by the fire and tried to see into the courtyard. Even from their limited view of the interior it was clear that the sailors were excited and frightened by the prospect of a pitched battle with the army units that were marching from Potsdam.

After about fifteen minutes an armed sailor took them inside and upstairs. Esser, typically, had bivouacked in the Empress’s private apartments, and that is where they were taken. Although the whole place had been ransacked, many of the personal possessions of the royal occupants were in evidence. Lace jackets and long ball dresses were still hanging in the Empress’s dressing rooms. Her writing desk had been broken into, and sheets of stationery and envelopes were scattered round, presumably by those people who’d been hawking examples of the royal correspondence round the streets. On the floor were powder boxes, some hairbrushes, combs and silver frames from which photos had been wrenched.

And yet the overall impression of this sanctum was of charmless vulgarity, an ostentatious collection of frivolous knick-knacks that might be expected in the house of some nouveau-riche tradesman.

‘The chairman of the sailors’ and workers’ emergency committee will come in five minutes,’ announced a bearded sailor.

‘Is that Fritz Esser?’ Pauli asked.

‘Yes, Comrade Esser,’ said the sailor. ‘You are not permitted to touch anything or to leave the room on pain of death; do you understand?’

‘Yes, we understand,’ said Leutnant Horner. He had by now grown used to the extravagant rhetoric of the revolution.

For ‘Chairman’ Fritz Esser of the People’s Naval Division it had been an eventful day, even when compared with the other crowded days of the past few weeks. But, as had happened so often since those early days of November 1918, he’d been outguessed and out-manoeuvred and eventually shouted down.

The trouble was that Esser never properly evaluated his opposition. It had been like that right from the time the naval mutinies began. Fritz Esser was usually the first to spot an opportunity, but he lacked the skill and cynicism to follow through his advantage.

For instance, the Spartacists and the left-wing radicals of the Independents had always expected that the revolution, about which they’d talked for years, would begin amongst the tired, frightened and exhausted front-line soldiers, rather than amongst sailors or civilians. It was Fritz Esser who’d persisted with his secret meetings and inflammatory leaflets directed at the crews of the battleships and battle cruisers of the High Seas Fleet, which had spent almost the entire war anchored in the Northern ports.

It was Esser – in a secret report to one of Liebknecht’s acolytes – who’d told them that fighting men would be the last ones to mutiny. That was evident here in the seaports, where there was little interest in Karl Marx amongst the U-boat crews or the men who’d chosen dangerous duty with the torpedo boats and destroyers that regularly sailed out to fight the enemy. The men who came to his meetings were the crews of the big ships: conscripts from the cities, bored, discontented men who chafed at the restrictions of military life and had nothing to do but parade, chip rust and paint their towering steel prisons. These men, who had never heard a shot fired in anger, were the ones who listened to Esser’s dreams of tomorrow.

Even the previous summer, after Esser had encouraged men of the battleship Prinzregent Luitpold to walk ashore at Wilhelmshaven in defiance of orders – a crime for which two of Esser’s fellow believers faced an army firing squad – the Spartacists did not believe that the High Seas Fleet was a fertile ground in which their agitators could scatter the seeds of revolution. Esser’s reports were ignored. In September a Spartacist leader told Esser that the Naval High Command’s reforms – ‘food committees’, elected by the sailors, were henceforward to distribute the rations – had removed the promise of further revolt.

It was only when, posted to Kiel, Esser had got the real mutinies going there that the Spartacist leadership started to take notice. But even then they were lukewarm and pointed out that the mutiny was only a reaction to being ordered to sea for a final suicide battle with the British navy. The Spartacists’ political committee in Berlin seemed offended by the fact that the sailors lacked political motivation. They insisted that this mutiny would never become the workers’ revolution they wanted.

Esser and his friends ignored the dicta from Berlin. It was one of Esser’s young disciples whose speeches prompted the stokers on the battleship Helgoland to draw their slicers through the coals, bring them out on the floor plates, and damp the fires with the hoses. Without heat enough to make steam Admiral von Hipper’s order to put to sea could not be obeyed.

And when the U–135 threatened to torpedo the Thüringen unless its mutineers surrendered, it was one of Esser’s converts who persuaded the Helgoland’s gunners to level their sights at the submarine. That Esser wasn’t present for this fiasco, which ended with the mutineers in prison, did not change his proud claim to have started the revolution. For within a few days not only Kiel but dozens of other towns and cities as well were under the control of workers’ and sailors’ councils. The army did nothing to put down the revolt: it was too widespread.

And so, when Esser got to Berlin with the vanguard of the mutinying sailors who now called themselves the Volksmarine or People’s Naval Division, he expected to be greeted with praise and thanks by the Spartacist hierarchy. But Esser was brushed aside as the politicians took control of the revolution in which they had shown so little belief. Esser became no more than a minor party functionary, a chairman for a committee that until today was asked to do nothing more important than arrange duty rosters for the cleaning of the billets and settle disputes between the numerous drunks, thieves and petty criminals who soon attached themselves to the sailors.

The important decisions about Spartacist policy – or lack of any – were being made by the same people who’d given Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg such bad advice in the past. Self-serving men with hard eyes, dark suits and sharp city accents dismissed Esser and his like as country bumpkins without the sort of political sophistication that was needed to steer the forthcoming revolution, which would sweep the temporary socialist government from power and replace it with uncompromising authoritarian rule.

And yet the men and women who could hear only Esser’s country accent would have done well to study his conclusions, for Esser was shrewd and perceptive. Esser’s report on the irregular army formations – Freiwillige Landesjägerkorps or Freikorps – now springing up all over Germany was something that Spartacist leaders would have done well to read. Esser had become an expert on discontent, and he was able to distinguish the discontent of the sailors he’d helped to bring to a state of mutiny and the sort of discontent that was furnishing the Freikorps with more men than they could properly clothe and arm.