По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

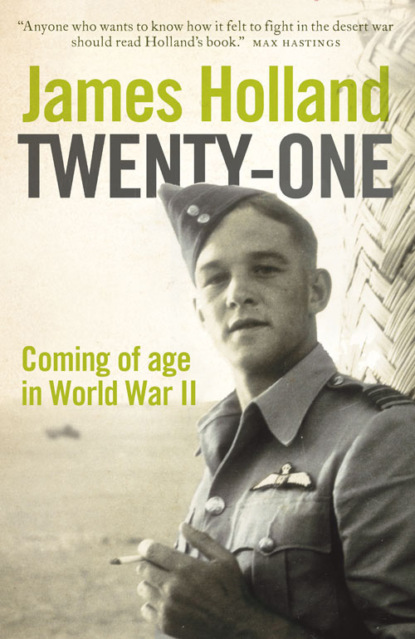

Twenty-One: Coming of Age in World War II

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

His crew did their best to help him, but it was difficult. ‘There was little I could say,’ said Dick Meredith, who moved into George’s old bed to keep Bill company. ‘We did do a bit of praying back then, and secretly I couldn’t help thinking that the Lord could not possibly be cruel enough to take both George and Bill. I thought Bill had to come through, and that gave me a sense of reassurance really. It was probably the wrong thing to think, but I couldn’t help it.’

Somehow, Bill kept going. On 18 November, they were on another mission, this time part of a raid on Mannheim. Strong winds of over a hundred knots pushed them way off course and so they hit Frankfurt instead. The following night, unusually, they were out again, this time to Leverkusen. ‘I think that if I had stopped I might have broke down,’ Bill told me. He also wanted to be there in case any news did come through. There was a chance George and his crew had been made prisoners of war – lots of them had, and it usually took about four to six weeks for word of POWs to filter through to the Red Cross. Six weeks came and went, but still Bill refused to give up all hope.

The rest of the crew never mentioned it. Some had lost good friends. Everyone lost someone. The statistics of the Allied bomber offensive are chilling: just over 110,000 men flew with the RAF’s Bomber Command; 55,000, almost exactly half, lost their lives. The US Eighth Air Force, joining the battle in 1942, lost 26,000 young men. Over 15,000 Allied bombers never came back – a staggering number, and a figure that equates to three-quarters of the numbers of Spitfires that were ever made. That Bill survived and George did not was simply conforming to the law of averages. ‘I don’t know what makes you press on,’ Bill sighed, ‘but you just do. There’s something in us … you know it’s crazy, but you still do it. It’s life itself. You know it’s dumb and stupid but you press on.’

By the end of November, the Battle of Berlin had begun. Bill’s fifth mission was what was labelled the ‘the first thousand-bomber raid’ on the German capital. In fact, only 764 aircraft took part, but the British press was happy to help with the propaganda. With the enemy capital deep in Germany, they could only get there by adding auxiliary fuel tanks at the expense of some of their bomb load. When they finally arrived, after nearly four hours in the air, Berlin was covered. The flak was intense, but despite the poor visibility, they could just about make out the red target indicator markers and the thousands of explosions pulsing orange and crimson through the cloud.

The bitingly cold winter and endless cloud and rain did not help Bill’s sense of gloom. ‘Boy, it was cold,’ he said. It was early in the New Year that he took his crew out on a flight above the clouds, just so they could see some sunlight.

And he also tried to keep his days busy, and to keep his mind on the job in hand. Routine helped. He’d be out of bed some time around seven or eight in the morning, then he’d shower, get dressed and head over to the mess for a breakfast of porridge and perhaps some toast. Then he would wander over to the Flight Room, where he would chat and wait with the rest of the crews, wondering whether they’d be sent out on a ‘war’ that night. There could be days without a mission, but they still made sure they looked at the daily routine orders. They might have to take their aircraft to the maintenance hangars or any number of tasks. After he was commissioned in December 1943, Bill ran the station post office for a while. ‘I didn’t know a damn thing about it,’ he said, ‘and it was in a hell of a mess when I took it over.’ It was another thing that kept his mind busy.

But he was rarely leaving the base. Just before Christmas, he decided it was time he tried to get out a bit, and so with a few of the others, went to a dance at the Catholic Hall in Northallerton. It was there that he first saw Lil.

Lil had been listening on and off to our conversation, sometimes sitting down with us in the lounge, sometimes attending to something in the adjoining kitchen. She now brought through some tea. ‘Tea,’ said Bill, his face brightening. ‘We always drink plenty of tea here!’ Then he got up and disappeared – he had some pictures and other bits and pieces to show me, but had to dig them out from the study next door. I asked Lil about this first meeting. ‘It wasn’t that night. He saw me, but I didn’t see him. I remember it was so crowded you could hardly move,’ she told me. She’d been taken by a young sailor friend and they began dancing. ‘But he was all over me and I thought, “This is no good,” so we left.’

Soon after, Bill was back, jiggling his leg up and down and sipping his tea, so I asked him about his side of the story. He grinned. ‘She walked in with her head held high,’ Bill said, ‘and she had nice long blonde hair.’ He immediately decided he had to dance with her, but he couldn’t reach her – by the time he got to her side of the dance-floor, she was gone. Still, it gave him an incentive to go again, and sure enough, a couple of weeks later she was there once more – and this time there was no sign of the sailor. Plucking up his courage, he went over to her and asked her to dance.

Afterwards, he walked her home. She, too, had lost a brother – a Flight Engineer and also on bombers – and in the weeks that followed, they began to see more and more of each other. Every fifth week, the crew would be given seven days’ leave. Some went to London, while others, like Bill Morison, would play golf, sometimes at Ferndown near Bournemouth, sometimes even at St Andrews, in Scotland. Bill, however, spent his leave with Lil, at her parents’ house in Northallerton. Then, in the spring, he asked her to marry him, although he told her they should wait until after he had finished his combat tour. ‘We were losing a lot of guys,’ said Bill, ‘and I was still operational.’ Did Lil worry about Bill? ‘No,’ she said quite firmly. ‘You have faith. It was a way of life; you took one thing at a time.’

Bill was also extremely lucky to have the crew he had. Crews tended to find each other on arrival at their Operational Training Units. There had been five of them at first, then at Croft, when they converted to four-engined bombers, two more had joined them. The same seven men had stayed together ever since. Close friends on the ground, they discovered a perfect working relationship that depended on mutual respect and complete trust. ‘All of them were brilliant,’ Bill admitted. Once the war was over, they all kept in touch, despite going their separate ways. The sense of camaraderie they had felt had been intense. Bill freely admits they were the closest friendships he ever made. Sixty years on, only Bill, Bud Holdgate, (the mid upper gunner), and Bill Morison, are still alive; Dick Meredith died in November 2005. They don’t see each other so often now – Bill Morison is in North York, Ontario, although Bud is from Vancouver – but they do speak regularly. Bill gave me Bill Morison’s and Dick Meredith’s numbers and when I was back in England, I called them. Both were anxious to help and equally quick to heap praise on Bill and their other friends in the crew. ‘Once the engines were running, we became a real team in every sense,’ said Bill Morison, in his gentle and measured voice. ‘We welded perfectly.’ Dick Meredith had been a farmer before the war, a reserved occupation, and could have avoided active service, but admits that he would not have missed the experience for anything. ‘They were all great guys,’ he told me, ‘and we were a dedicated bunch. We were a very good crew, all of us, and we never stopped learning.’

As the weeks and then months passed, so the crew’s number of missions began to steadily mount – ten were chalked up, then fifteen, then twenty. They went from being the new boys to the most senior and experienced crew in the squadron. Bill was commissioned in December, while at around the same time Bill Morison became the squadron’s navigation leader: it was now up to him to not only help plan their routes to the target, but also improve the standard of the less experienced navigators.

Casualties during the Battle of Berlin, which lasted from November to the end of March 1944, were particularly high – 1,128 Allied bombers were shot down during this period, a staggering number. Yet every time they went out on a ‘war’, Bill and his crew miraculously seemed to make it back in one piece. ‘Once you’d done five or six,’ said Bill Morison, ‘your chances were improved, but you could still get shot down at any time. The fact that you were a very experienced crew didn’t guarantee anything.’ On 24 May, 1944, the squadron took part in an attack on the German town of Aachen. Fifteen aircraft took off, Z for Zebra included, and made it safely to the target. There was little flak – the raid appeared to be one of their more straightforward missions, but on the return home, they came under repeated attack by night-fighters, and three of the squadron’s Halifaxes were shot down. All those lost had been experienced crews, the backbone of the squadron for many months. One had even been on their last mission – had they made it back to Leeming, their tour of duty would have been over.

Yet although Z for Zebra continued to make it back almost unscathed, these missions were not without incident for the crew. On one occasion Bill had thought they would never even manage to get airborne. There had been a strong crosswind and the aircraft had started to swing so badly as they hurtled down the runway that he’d thought he would lose control and flip the plane. Another time one of his port engines caught fire almost as soon as they’d left the ground. It was 30 March, 1944, and they were due to bomb Nuremburg.

‘That was scary,’ he admitted. ‘Fire in the air like that is scary. You can’t just land again – not with all those bombs and full tanks of fuel.’ A pipe had burst and petrol was spewing everywhere. Bill had to cut the engine immediately, but ahead was a small hill and with a quarter of their power gone, it looked as though they were not going to get enough lift and so fly straight into it. Somehow, though, he managed to clear it, and was able to get to the North Sea and discard his bomb load. He still had to burn off much of the fuel, so circled for a couple of hours before finally turning back to Leeming. They’d had a lucky escape. The girls in the control tower thought they must have crashed and so when he called up and gave his call-sign, ‘Must We’, they thought they were talking to a ghost.

Landing was potentially more dangerous than taking off. Although they never flew in formation, aircraft could frequently land within minutes of each other. Often the Halifaxes would be damaged, and were nearly always low on fuel. ‘One night my hydraulics were shot away and I couldn’t use the flaps and even the undercarriage didn’t want to come down.’ This was where experience came in. Bill eventually got the wheels down by diving the aircraft and then pulling back up; the force of gravity eventually locked them into place. Even so, without flaps, he hit the ground at 170 knots rather than 130. ‘I went off the end of the runway,’ he said.

Having finally landed and switched off the engines, a van would arrive and take them off for debriefing. There was coffee and a slug of rum, but Bill never touched either. Back then, he was not a great drinker. ‘I can make an ass of myself without drinking,’ he says, ‘that’s the way I look at it.’ The Intelligence Officer would ask them about the mission. What did they see? Were they attacked? What was their view over the target? Each of the Halifaxes had a camera. As soon as the bombs were released they would take pictures, with the fourth snapping as the bombs hit the ground. ‘You couldn’t come back and say, “We definitely hit the target.” You had to wait for the pictures to be developed for that.’ Bill tells me about the time one aircraft went out on a mission then flew up and down the North Sea. Unbeknown to the pilot, he was being tracked by British radar and when he returned had not taken any pictures either. ‘He was scared. There were people … sometimes people broke down.’ Not that Bill ever saw anyone really fall to pieces. Those suffering from shattered nerves were whisked away off the station immediately, before the other men could see. ‘LMF,’ said Bill. ‘That’s what they called it. Lack of Moral Fibre. But you could only take so much; everyone will break down after a while.’

But not Bill, despite chalking up over thirty missions in ten months of front-line duty. ‘I was lucky. A very lucky pilot,’ he told me. One time, they were flying over Germany. It was quite dark – they were nowhere near their target – when tracer started streaming past and cannon shell bursts exploded in front of them. They’d been picked up by radar and now had a night-fighter attacking them. Bill immediately changed course, weaving back and forth as shells continued to explode either side of him. In the end he was forced to ‘corkscrew’ and eventually managed to shake off the enemy fighter. Another time they were flying over a city and flak – anti-aircraft shell bursts – began exploding all around. A near explosion could severely jolt the aircraft, but on this occasion Bill had just dropped his bombs and had selected the bomb doors to close, when the flak burst beneath them and flipped the Halifax onto its back. ‘The gyro was telling me I was upside-down, and we were falling fast, so I immediately rolled out of it.’ But they were still in a dive, with the airspeed indicator pointing at over 300 miles per hour, far in excess of the Halifax’s maximum speed. ‘I thought, “I’d better not pull out too fast or I’ll pull the wings off,” so I kept the throttle back and let her slow down a bit.’ Eventually they levelled out and began climbing once more. But in that short space of time, they’d dropped around 5000 feet. ‘I heard a hell of noise from the airplane, but the strangest thing was we suffered no damage at all. We checked everything. The crew had been holding their breath and I heard a loud “Pheww!” once everything had been ticked off.’ Bill chuckles. Another time they came back and there were 173 holes in the plane. But they’d still made it home.

They could often be in the air for long periods of time, especially if flying to Germany and back. Not only did he have to concentrate on piloting and be ready to take evasive action at any moment, he had to do so in freezing temperatures. At the kind of height they were operating from – and the higher they flew the safer they were and the better the engines ran – temperatures could drop to fifty below. ‘There was heat coming off the engine,’ said Bill, ‘but no insulation. When it’s that cold, you soon feel it.’ He always wore silk underwear, silk gloves and a long white silk scarf under his flying jacket, so managed to keep his upper body warm enough. The problem was his feet, with which he operated the rudder. ‘Most of the time, I couldn’t really feel them.’ Despite the length of some journeys and the mental and physical exhaustion these missions entailed, he rarely felt too tired to fly. ‘If I did, I’d open the side window and that cold air would slap me round the face.’

As well as relieving himself before he got into the plane, he also always needed to go as they began the bomb run. ‘It was strange. I’ve never had the strongest kidneys, but I’d have to pull out and pee into this pipe. It led straight out and would just suck out the moisture. So I peed on every German city I flew over …’

What about dropping bombs on civilians? I ask him. ‘You don’t think about the people getting hit,’ he said. ‘I didn’t build the airplanes; I didn’t build the bombs; I didn’t gas them – I just went there and back – the guilt was shared by all of us, you know.’ He paused again, then said, ‘You can’t help but feel a certain amount – well, you wished it never happened, at any rate. You can’t divorce yourself from it because you had something to do with it, but I don’t feel responsible for the whole thing.’

On D-Day, he and his crew took part in their first-ever daylight mission. Nearly a thousand of Bomber Command’s aircraft were directed against the Normandy coastal batteries. Crossing the Channel as dawn was breaking, navigator Bill Morison suddenly noticed hundreds of white blips on his H2S radar set. Informing his skipper, they soon after saw the sea full of ships from one end of the horizon to the other. Like everyone else, they had been kept in the dark about exactly when the landings would be. Despite this exciting bird’s eye view of the invasion, they found the experience unsettling. In order to improve their accuracy, they flew over the target at 10,000 feet, far lower than they were used to. ‘There were not many enemy fighters,’ recalled Bill Morison, ‘but the flak was definitely a problem.’

They flew a number of other missions over Normandy, until, on 18 July, 1944, they chalked up their final and thirty-fourth mission as a crew – Bill had flown two more than the rest. It was an attack on German flying-bomb sites near Caen, and was largely uneventful – they found their markers, dropped the bombs, then Bill banked the plane, pulled back on the control column, climbed the Halifax to safety, and turned for home. Afterwards, there was a little bit of rejoicing, but not too much. Their relief at surviving was marred by the knowledge that they would now be split up and sent to different parts of the country. Their services were now needed as instructors to train the final batches of crews in the endgame to the bomber war. They were briefly reunited a few weeks later, however. Although the war still had ten months to run, Bill’s combat flying career was now over so he and Lil decided to marry right away. ‘It was a very happy occasion,’ said Bill Morison, who, in the absence of George, was the best man.

Bill still hadn’t given up complete hope for his brother, and when the war was finally over, he went back down to the south coast to meet the POWs coming back. ‘I talked to lots of them – some I even knew. I wanted to check whether anyone had heard anything about my brother’s crew.’ They hadn’t. By the time he finally returned home to Vancouver, he had become ‘300 per cent certain’ his brother had gone down into the sea that night. ‘You’ve got to have hope and your mind rolls over all kinds of possibilities, but eventually …’ George’s navigator came from British Columbia too. He’d been married with a couple of kids and his father came down to see Bill. He wanted to know whether there was any chance that his son was still alive. ‘And even though you want to give them hope, I said no. No way.’

It was, he admitted, a hard thing to say, but added, ‘Well, wars make you hard. I used to take care of the chart that listed the crews. When the guys got shot down it was my job to take them off and put a new name on there. The first time I rubbed a guy’s name off – gee whiz, it hurt me. He’s gone. Shot down. No more. But after a while I was just going through the motions. I’m telling you: people get hard.’

We looked through Bill’s old photographs. There were a number of him and George together from their flying training days. It’s uncanny, but they really did look identical. Same smile, same eyes, same hair. You could see why any girl would have fallen for them. There was his citation for his DFC, and old newspaper cuttings, too. Local newspapers often proudly reported the progress of their gallant sons and the Byers’s corner of Vancouver was no exception. One piece was about them joining 429 Squadron together. ‘When they arrived on the squadron, the boys craved action. They got it. Within 24 hours they were off on their first operation. “We sure are glad we have been able to stay together,” said Bill.’

Bill still thinks a lot about George. ‘I wonder what kind of life I would’ve had if he’d been here. He was the only brother I had and we were so close, you know.’ And what about the war? Do you still think about it a lot? I asked. He paused a moment and said, ‘The war seems like a dream now. After the war, nobody talked about anything – it wasn’t until about ten years after that you started to get some books on it, but it takes thirty or forty years before a person wants to tell his experiences or say anything about it and then it relieves him somewhat.’ He paused again. ‘It makes it easier as time goes on; your mind gets a little more reasonable with it. I don’t mind talking about it now. Time heals. In a way it’s better to share it with somebody. It helps you.’ Another pause and Bill looked at some distant spot on the wall. ‘I think it does anyway.’

Tom & Dee Bowles (#ulink_d514ea31-7652-58f4-8ad7-964e4eefac05)

May 1944, with the Allied invasion of Northern France just a few weeks away. For the past six months, the US 18th Infantry Regiment has been based in a large camp between the villages of Broadmayne and West Knighton, outside the county market town of Dorchester. It’s rolling, green countryside, at the heart of Wessex, in the southwest of England. And on this particular May evening, Privates Tom and Dee Bowles and several of their friends from Battalion Headquarters Company have been given a pass out of camp, and so have headed to one of their favourite haunts, the New Inn at West Knighton. It is a traditional English country pub, quite different from the bars back home in America, but the GIs of the 18th Infantry have always been made welcome there. They’ve even developed a taste for the beer …

It’s Tom Bowles who is the photographer: all through their training in the United States and in Britain, and through the campaigns in North Africa and Sicily, he has taken pictures – often surreptitiously – and he has brought his camera with him this evening. Having bought their pints, the young men step outside once more; after all, it’s warm enough. There are some old beer barrels outside – it’s the perfect picture opportunity, and so Tom gets out his camera and they begin taking snapshots of each other. In one, the Bowles brothers stand around the barrels, clutching their pints, alongside their buddies Dotson and John R. Lamm. In another, the two brothers perch on the broken brick wall at the entrance to the pub. They make a handsome pair in their dress uniforms: square-jawed, with high cheekbones and dark, serious eyes and just a hint of swagger – each has an arm casually draped over a leg; they’re adopting matching poses. It’s hard to tell them apart. There’s confidence there, too, on the faces of these twenty-two-year-olds; it’s not just the row of medal ribbons across their chests, or the way they brandish the shoulder badge of the First Infantry Division – the Big Red One. If they’re worried about the forthcoming invasion – an operation they know will be happening some day soon – they certainly aren’t showing it.

Many years later, the film will be rediscovered, and in perfect condition. When it is developed, the pictures that emerge are so fresh and clear, it’s as though they’d been taken the day before. It is hard to believe the reality – that they were snapped on a warm evening in May more than fifty years earlier, just a couple of weeks before one of the most momentous moments in history.

Only a few days after their trip to the New Inn, Tom and Dee (as in Henry D. Bowles) were handing in their ties and dress uniforms and being given their kit for the invasion: new gas masks, gas-proof clothing, and even anti-gas ointment to put on their shoes. It was unusually warm that May and as they began wearing these new gas-proof clothes they all began to sweat badly: the new kit was almost totally air-tight. New canvas assault jackets with extra pockets on the front, sides and back, were also issued. So too were plastic covers for their rifles and weapons. Each man was given a fuse, lighter and a block of TNT – just large enough to blow a hole in the ground that could be then made into a foxhole; these would have been handy back in North Africa where the soil had been thin and the rocky ground hard as iron. Further instruction in first aid was given to every man, and extra sulfabromide tablets handed out. Each man would be carrying nearly eighty pounds of kit: clothing, first aid, weapons, ammunition, canteens, rations, and even candy, cigarettes and toilet paper.

Despite this increasingly frenetic activity, neither Tom nor Dee was unduly worried. During the past few months they had practised amphibious assaults, trained in bomb-damaged houses in nearby Weymouth and listened to the generals who had visited them and given them pep-talks. Large numbers of fresh-faced GIs had arrived from the United States to bring the companies, decimated from campaigns in Tunisia and Sicily, back up to full strength and beyond, but for the old hands like Tom and Dee, who had already been through two amphibious invasions, it was hard to get terribly excited about practising an assault on a concrete pillbox somewhere in southern England.

Then one day, at the very end of May, Tom and Dee came back from a visit to the nearby resort of Bournemouth to discover that they were now restricted to quarters, with British troops patrolling the wire perimeter. No one could get in or out without a special pass. ‘I hadn’t really given the invasion that much thought until then,’ admits Dee. The following morning, they watched as the battalion’s officers were marched to the former staff officers’ quarters. The doors were then locked and guards placed outside.

When the officers reappeared and rejoined their companies, the rest of the battalion were finally given their briefing. Tom and Dee were both in the same company; Tom had been in Company G throughout North Africa and Sicily, but had joined his brother in Battalion Headquarters Company since arriving back in England the previous November. He’d been part of a mortar team up until then, but he wanted to be closer to his brother and figured that since he’d lost a lot of his buddies whilst on mortars, becoming a wire-man like Dee was a safer bet. Brothers were not supposed to serve in the same regiment, let alone the same company, and especially not if they were identical twins, but somehow Tom and Dee managed to get round that one. They’d been together almost since the day they joined the army and they weren’t going to be split up now. And so it was that they heard about their upcoming role in the invasion of France together.

The Big Red One was going to land in Normandy, east of the Cotentin Peninsula, along a four-and-a-half-mile stretch of coast to be known as Omaha. The beach was overlooked by 150-feet-high sandy bluffs, impassable to any vehicles except at four points – or exit draws – where roads ran down to the sand. The first wave of assault troops was to land early in the morning of D-Day, clear the beaches of mines and other obstacles, secure these four exits and then a few hours later, the next wave would arrive and, passing through the first wave, break out beyond the beachhead. Simple. The 2nd Battalion was to spearhead the second wave, coming in behind the Sixteenth Infantry on a sector of the beach to be known as ‘Easy Red’, smack in the middle of Omaha, and covering the ‘E-1’ exit draw. This at least was something: in their previous two invasions, Tom and Dee had been among the first to land. Now they would be three-and-a-half hours behind.

Several days went by. They felt restless in their camp, but there were some perks. At one end of the camp there was a large store full of candy and cigarettes. ‘They had cigarettes of all kinds down there,’ says Dee, ‘and you could take what you wanted.’ He didn’t smoke, but he took a whole load anyway. ‘I figured I could trade with them later,’ he admits. They also had some drink to take with them. On their trip to Bournemouth they had bought a bottle of whisky and a bottle of gin. Each man was to take two water bottles, so Dee filled one of his with whisky and Tom filled one of his with gin. ‘I don’t know whether we thought we were going to celebrate or what, but it seemed like a good idea at the time,’ says Tom.

Then on Sunday, 4 June, they were told to get ready to ship out. The men were given one last hot meal, then at dusk clambered into trucks and were taken down in convoy to Weymouth harbour and loaded onto waiting troopships. By the time Tom made it aboard the ship, it was almost bursting at the seams with men. ‘I found myself a tiny cubby hole,’ he says, ‘then curled up and went to sleep.’ When he awoke the following morning it was to discover that the invasion had been postponed for twenty-four hours. Tom was struck by the huge queues waiting outside the chaplain’s quarters. ‘The line was completely up and round the ship,’ he says.

Even when the invasion fleet finally began to inch out of harbour on the night of 5 June, Dee and Tom still remained calm. They’d always been pretty easy-going people, about as laid back as it is possible to be in a time of war. ‘Being a soldier was our life at that time,’ says Dee. ‘I know some guys that worried about getting home to their wives and all, but we didn’t have that. We really just had each other and the battalion, and we knew we weren’t going to get back to the States until the war was over.’ He pauses, then adds, ‘So to me the invasion was just another job. Neither of us worried too much about it.’

By May 1944, Tom and Dee really were on their own. They had lost both parents, and although there was a kid sister and five much older half-sisters from their father’s first marriage, from the moment they joined the army they considered it as home. Identical twins, they were from America’s Deep South, in north west Alabama. Life was tough, very tough, during the Depression-hit 1930s. The family was poor, although both Dee and Tom claim they were happy enough, with always plenty to eat and enough going on to amuse themselves. There was sadness, however. Tom and Dee were no exception, losing first a brother and then their mother when they were just twelve years old. Their father was a farmer, growing fruit and vegetables that he would then load onto a cart and sell in town, but being a smallholder at that time was hardly lucrative in the Depression-era Deep South was hardly lucrative, and so soon after their mother died, the family moved to the cotton-mill town of Russellville. The twins left school and went out to work – the extra bucks they brought home made all the difference.

By 1940, however, the cotton-mill in Russellville was already in terminal decline, even though the rest of the country was lifting itself out of the Depression. ‘We wanted to go to work,’ says Tom, ‘but there wasn’t no work around.’ They’d applied for places in the Civil Conservation Corps – a scheme set up by President Roosevelt to try to combat massive soil erosion and declining timber resources by using the large numbers of young unemployed. But they were turned down. Instead, in March 1940, two months after their eighteenth birthdays, they decided to enlist into the army. Of the two, Tom tended to be the decision-maker, so he was the first to hitch a ride to Birmingham in order to find out about joining up. Since they were only eighteen, their father had to give his consent. ‘I remember his hand was pretty shaky when he signed that,’ says Tom. Four days later, on 9 March, Dee followed. ‘We hadn’t heard from Tom,’ says Dee, ‘so I told Dad I was going too. He said, “Son, make good soldiers,” and we always tried to remember that.’ After being given three meal tickets in Birmingham and a promise of eventual service in Hawaii, Dee was sent to Fort Benning in Georgia, one of the country’s largest training camps. He still wasn’t sure where his brother was – or even if he had actually enlisted – until eventually he got a letter from his father with Tom’s address. It turned out they were only a quarter of a mile apart, and that both were in the 1st Infantry Division, even though Tom was in the 18th Infantry Regiment and Dee the 26th.

In 1940, the US Army was still a long way from being the huge machine it would become just a few years later. There may have been some thirteen million Americans in uniform by June 1944, but less than ten years before, there were just over 100,000, and by the time Tom and Dee joined, the US Army was still languishing as the nineteenth-largest in the world – behind Paraguay and Portugal – and much of its cavalry was exactly that: men on horseback. Tom even has a photo of the cavalry’s horses massed in a large pasture at Fort Benning.

Unsurprisingly, their basic training was pretty basic. On arrival at Benning they were told to read the Articles of War, then were given a serial number and told to make sure they never forgot it. After eight weeks training – drill, route marches, occasional rifle practice, and plenty of tough discipline – they were considered to be soldiers. They were living in pup tents, but eating more than enough food and surrounded by young lads of a similar age, so as far as the Bowles twins were concerned life in the regular army seemed pretty good, and a lot more fun than back home in Russellville, Alabama.

Training continued. More marching – three-mile hikes, then ten miles, then twenty-five miles with a light pack and eventually thirty-five miles with a heavy pack. A mile from home, they were greeted by the drum and bugle corps who played them the last stretch back into camp. But while this was doing wonders for their stamina and levels of fitness, they had little opportunity to train with weapons. Their kit was largely out of date too: World War One-era leggings, old campaign hats, and Tommy helmets, and although most in the 1st Division had now been issued with the new M-1 rifle, they rarely saw any tanks and the field guns mostly dated from the First World War. In July 1941, they were carrying out amphibious training in North Carolina when they received telegrams that their father was critically ill. Given compassionate leave, they were put ashore and hitch-hiked back home to Alabama. ‘Daddy died on July 31st, 1941,’ says Dee. He was just fifty-four; he had suffered his third stroke.

Soon after, their younger sister joined the air force, and Tom and Dee rejoined their units – in time for the Big Red One’s participation in the Louisiana Maneuvers of August 1941, the largest military exercise ever undertaken in the US, in which two ‘armies’ were pitched against one another. They were designed to test staffs and the logistical system as much as anything, but having seen the National Guard divisions still carrying wooden rifles and lorries with logs on that were supposed to simulate tanks, both Dee and Tom began to realize just how unprepared America was for war.

They were both on leave when Pearl Harbor was attacked by the Japanese. There had been talk of war for some months, but now they were in it for sure. They also knew that since the First Division was one of the few pre-war regular army units, they were likely to be among the first in action – although they didn’t have the faintest idea when or where that might be. And for the first half of 1942, they remained in the US, moving from camp to camp, practising amphibious landings, carrying out more marches and exercises, sometimes on sand, sometimes in the snow. ‘All we were doing was moving from one location to another and getting ready to fight,’ says Dee.

Not until 2 August, 1942, did the twins finally find themselves steaming out of New York en route to Britain. Like most young men heading off to war, it was the first time they had ever left home shores. The entire First Division was crammed onto The Queen Mary, one of the great pre-war transatlantic liners, but as Tom and Dee discovered, there was little that was luxurious about the great ship now. It had been designed to carry two thousand passengers, but on 2 August, 1942, the Queen Mary was carrying 15,125 troops and 863 mostly British crew. ‘It sure was crowded,’ admits Tom. They were given hammocks, four banked on top of each other along each wall of a cabin. Although still in different regiments and in different cabins, they managed to see plenty of each other, and despite being packed like sardines, they didn’t find it too much of a hardship. ‘Well, to us it was rather like being on a vacation,’ says Dee. They were given plenty of hot meals, each eaten at a table and served by waiters. The threat of U-boats was ever-present, and there were not nearly enough lifeboats for the number on board, but it didn’t worry the Bowles twins too much: the ship was fast, and it continually zig-zagged all the way to avoid the German submarines. As they approached the British Isles, aircraft arrived to escort them over the final part of the journey into Gourock in Scotland.

They docked on the morning of 7 August, beneath the dull-grey barrage balloons that floated above the harbour. The division was quickly ushered off the ship past a line of women handing out cups of tea and then led straight onto waiting trains. The Bowles twins, separated once more into their respective regiments, still had no idea where they were heading, but it soon became clear the final leg of their journey was not a short ride. British officers appeared, demonstrating in each compartment how to pull down the blinds; the blackout was something new to the American troops. The train chugged on through the night, past nameless towns and villages, until at around seven the following morning they finally reached their destination. Tidworth Barracks, some ten miles north of Salisbury in southern England, was shrouded in early morning mist as the soldiers stepped down onto English soil for the first time. On Salisbury Plain, one of the British Army’s largest training areas, the Bowles twins and the rest of the division would begin preparing for the largest seaborne invasion the world had ever known – not D-Day, but the Allied landing in Northwest Africa.

Shortly before the TORCH operations in Africa, Dee had managed to transfer regiments and was now with his brother Tom in the 2nd Battalion of the 18th Infantry, although he had joined Headquarters Company, while Tom remained with his mortar crew in Company G. As a result they both landed on African soil at around the same time, on a sandy beach just east of the port of Arzew in Algeria, on 8 November, 1942. They would find themselves up against stiffer opposition in the months and years to come, but in fighting the Vichy French – at that time still collaborating with the Axis powers – they faced their first time in action. It was on that first day, whilst taking cover in a cemetery near the town of St Cloud, seven miles inland, that Tom saw his first dead body. ‘I saw him lying there,’ he says, ‘and that made a big impression on me. I thought, this is for real now.’ Of all the horrors they would witness before the war was over, this first corpse affected Tom the most.

Both agree that war makes a man harden up pretty quickly. French resistance quickly crumbled and French North Africa – all those troops in Algeria, French Morocco and Tunisia – joined the Allies. While the British Eighth Army advanced from the east after their victory at El Alamein, the joint US and British force that had landed in Northwest Africa advanced from the west. The joint German and Italian armies were slowly being caught in the vice of Tunisia.