По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

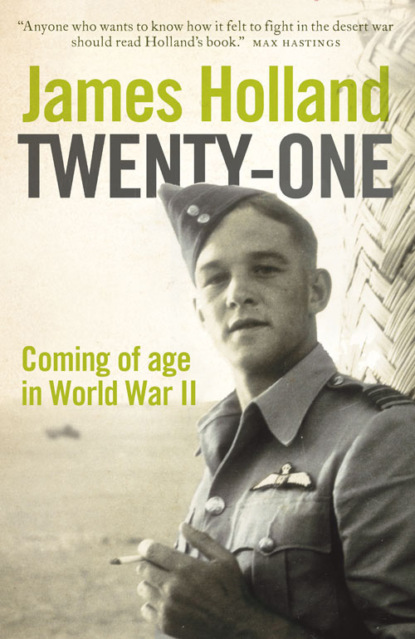

Twenty-One: Coming of Age in World War II

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Tom reckons that that battle for Aachen, King Charlemagne’s capital in the Middle Ages and the first major city inside Germany, was the worst he ever fought. ‘That topped D-Day for me,’ he says. By the beginning of October, the Big Red One had moved into Germany and was holding a line roughly south and east of the city; the attack was to be launched on 2 October, with the 2nd Battalion of the 18th Infantry given the job of capturing the town of Verlautenheide to the east of the city. Having done this, they were then to prepare defensive positions against possible counter-attacks from the German garrison in Aachen itself.

Tom was given a glimpse of what was to come when he first approached the edge of the town on an eerily misty October morning. A knocked-out car lay to the side of the road and sitting on the roof was a body – with no legs, no arms, and no head. ‘The torso was all that was left,’ says Tom. ‘I thought: this is going to be rough …’ The town was taken later that day, but Verlautenheide stood perched on the eastern end of a long ridge, and the fight for this ridge and the neighbouring Crucifix Hill was bitter and hard-fought with the Germans repeatedly counter-attacking. Headquarters Company was based in a three-storey building in the town, and Tom says that for four days and four nights he barely slept as they came under almost continual bombardment and had to repair damaged wires throughout the fighting. One night, Tom and his buddy had to mend a line down to H Company. Slowly, they inched forward, feeling their way through the darkness, the line as their guide. They stopped by a large tree that had been felled by the bombing near a building where H Company had set up their machineguns. They traced the wire, made the repair, and then called back to Company HQ to test it. But the line was still dead. So they crawled forward again. By now, they were doing everything they could to avoid being out in the open – at night, they were all too aware that one of the H Company machinegunners might mistake them for Germans and open fire. They mended another break, but again, the line was still dead. Eventually, they crawled all the way to the wall of the building and, sitting crouched under a window, could see that the wire led right inside. They called up Company HQ again. ‘The wire’s good,’ Tom told them, ‘so we’ll go inside and try and find out what’s going on.’ Suddenly, machinegun fire opened up from the windows above them.

‘Get yourselves back!’ Company HQ told them as Tom and his buddy frantically pressed themselves against the wall. ‘H Company’s not in that building anymore – the Germans are!’ As stealthily and quietly as they could, they crawled back to the comparative safety of the tree, then feeling their way along the wire, scampered back to safety.

Another time, Tom was crossing the cemetery next to the building where Company HQ was based, when two shells screamed over, one exploding only fifteen feet from where he was. The blast knocked his helmet forward and cut his nose. Otherwise he was fine, but as he got up again he heard someone shouting. ‘They’d just been bringing up some replacements,’ says Tom, ‘and one of them was hit.’ Tom hurried over and helped the man to the aid station. ‘I had his blood all over me as well as my own blood from my nose, so as I laid him down, these medics rushed over and asked me how badly I was hurt,’ says Tom. ‘It’s not me,’ he told them, ‘it’s this guy here.’ He has no idea whether the man he helped survived. Replacements were now coming in all the time, and, as he points out, ‘you were half-gone by loss of sleep’; there was little or no energy left to worry too much about others. It was whilst still at Verlautenheide that he helped another wounded GI. The man had been hit in his half-track and Tom was asked to help get him out. The man was heavy and it was not easy lifting him up, but Tom did his best and managed to get him to the cover of a building and lay him down. No sooner had he done so than the man gasped one last time and died. Tom looked down at him and saw he was wearing a crucifix round his neck. ‘I looked up,’ recalls Tom, ‘and said, “Well, he’s yours,” like I was talking to the Lord.’

By the time Company HQ moved again, only the basement of the building they’d been in remained. The storeys above them had vanished into a pile of rubble. Tom received a second Bronze Star – an oak leaf cluster – for his bravery under fire at Verlautenheide.

The fighting around Aachen lasted for the best part of a month, but later, after it had finally fallen, Tom and a friend took a jeep into the city where they came across a former German barracks and stopped to have a look around. The place was a mess – papers, clothing and furniture strewn everywhere. But Tom noticed a box on the top of a locker and reaching up, took it down. Inside was a very large Nazi swastika flag. He has it still to this day.

After Aachen, the First Division were sent south into the Hürtgen Forest, and there, with winter closing in, they suffered a brutal month. The forest was dense, full of mountains and hidden ravines, ideal country to defend, but nightmarish terrain through which to try and attack. During November, eight US divisions had tried to break through the Hürtgen Forest. ‘All,’ noted the First Division history, ‘had emerged mauled, reduced, and in low spirits.’ Casualties amongst the 18th had been as high as at any time during the war – a thousand dead and wounded. But what Tom particularly remembers is the near constant rain and the terrible, ghostly darkness. ‘I never saw such a dark place,’ he says. ‘If you went twenty yards from your foxhole, you’d get lost.’ The forest, he noticed, played tricks. One night, he was on guard duty and it was raining heavily. Near a road, he thought he could hear troops marching past. But he couldn’t see a thing, so he stepped towards the road and held out his arm to see if it would touch somebody’s raincoat as they marched past. He felt nothing. ‘It sounded as real as could be – tramp, tramp, tramp.’ But it was just the sound of the rain on the pine trees.

At the end of November, the depleted 18th were pulled out of the line and sent to a town in Belgium for a week’s R&R. It was their first proper rest since D-Day. They’d only been there a few days when someone came up to Tom and said, ‘Guess who I’ve just seen back at the depot?’ Tom didn’t have to guess – he knew who it was already.

After nearly six months in England, Dee was back. He could have been given a posting back home, but he was not having any of that. He wanted to be with his brother; and in any case, the 18th was home. Tom had mixed feelings about seeing Dee, however. On the one hand, he was thrilled to see him again – and looking so well – but on the other, he worried about him being back at the front. The experience of Aachen and the Hürtgen Forest had shown that there would be no easy victory. At least, though, they had this period of rest ahead of them, and with the shortening days and weather becoming even colder, it looked as though the front might stabilize for the winter.

And then a strange thing happened. They were talking in Tom’s room in the house where he was billeted and Dee had just handed over a bottle of Scotch that he’d brought back from England for his brother, when someone shouted, ‘Fire!’

‘And the building was on fire,’ says Dee – just an accident, it later turned out. ‘So we grabbed our rifles and every doggone thing else and got out of there.’ From the road outside, they watched the fire spread, then suddenly the window in Tom’s room blew out. ‘There goes that Scotch,’ Dee told Tom ruefully.

It was on 16 December that the Germans launched their last big offensive of the war, and it took the Western Allies by complete surprise. Under the cover of low cloud and misty, overcast conditions – the ‘season of night, fog and snow’ – the Germans had managed to gather, undetected, thirty-six divisions for a massed drive through Belgium to Antwerp, a thrust designed to split the Allied forces in two and sever their supply lines.

The 18th Infantry were still on R&R when, the following day, the news of the German attack reached them. Their leave was over: by three that afternoon, they were packed into trucks and were beginning to hurry to the front. The 2nd Battalion found itself holding a position south of the town of Bütgenbach, on what was soon to become the northernmost limit of the Ardennes salient – or ‘bulge’. By Christmas Eve, the German attack had run out of steam, crippled by lack of fuel, but what followed was two months of appalling attritional, warfare. In the Ardennes, the war soon began to resemble the worst horrors of the Western Front over twenty years before.

On Christmas Day, the big freeze started, and then came the snow, covering everything in a deep white shroud. The temperatures dropped below freezing and stayed there, and the Americans, with too much cotton clothing and not enough wool, began to suffer badly as they crouched in their foxholes and listened to the shells screaming overhead.

There’s another photograph of Tom and Dee, taken around this time. There’s still an air of swagger about them, but they look more serious, older even, although this may have something to do with the Errol Flynn moustaches they’re both sporting. Standing ankle-deep in snow, they’re wearing thick scarves around their necks and white camouflage covers over their tin hats. ‘The worst part of the Bulge was the snow and my clothes being froze,’ says Dee. ‘Course, we had thick pants over our other clothes, but we didn’t have snowshoes or anything. We just had our regular boots and a field jacket and anything else we could find.’ Their clothes became so frozen they would grate together like paper. They also suffered from German V-1 rockets, or ‘buzz-bombs’. They could hear them coming, like a persistent drone, then all of a sudden the engine would cut and they would hurtle into the dense fir forest where the battalion was crouching. ‘You didn’t know where they was going to land,’ says Tom, ‘so you’d lie there waiting for the bang.’ Huge craters would be formed, obliterating everything in their wake, and propelling shards of stone and lethal tree splinters in a wide arc.

But the guardian angel that had been watching over the twins since the day they joined the US Army continued her good work, although Tom and Dee both had their close shaves. Dee was even wounded again on their way back to the front. Having just passed through Bütgenbach, their column was attacked by Allied aircraft. One bomb landed no more than twenty feet from Dee, blowing him up into the air and onto the bank of the road and showering him in mud.

Tom found him a short while later, standing in the doorway of a building in Bütgenbach, covered in mud and blood. ‘But just by the way he was standing, I could tell it was Dee,’ says Tom, who then took him down to the aid station. After being cleaned up and bandaged, Dee rejoined Company Headquarters. ‘I didn’t go to hospital or anything,’ he says. ‘I’d already been separated from my brother once, so I just stayed with the outfit. I was fine soon enough.’

Tom had another eerie experience during the Bulge. He was with a new wireman buddy, a replacement named Private William White, and they were laying wires when shells started whistling overhead and exploding nearby. Taking cover by a fence, they waited for the barrage to lift, then heard voices up ahead.

‘I’m going to take a look at what’s going on,’ Tom told White. ‘You wait here and I’ll holler for you.’ Moving cautiously forward, he soon found a couple of badly wounded Germans. One had already passed out but on seeing Tom, the other asked him to shoot him to put him out of his misery.

‘No,’ Tom told him, ‘I’m not going to shoot you.’ He then called back to White, but there was no answer, and so he shouted again. But White still did not appear. So Tom went back to the fence where he had left White, but he was gone. ‘That son of a gun,’ thought Tom, ‘he’s deserted on me.’ He felt like shooting his buddy when he next caught up with him. Heading back to the command post, Tom reported that White had gone missing.

That night, it snowed again, and the following morning they moved positions, passing within a few yards of where Tom had been the previous day. He saw two mounds where the Germans had been – evidently they had both died and been buried under the snow. ‘I just looked at them and didn’t say nothing,’ admits Tom. Soon after, White was found, dead. ‘When I left him there,’ says Tom, ‘there must have been some Germans still in the area and they grabbed him after I’d gone forward.’ Later, as White had tried to escape, he had been shot. ‘It could easily have been me,’ says Tom.

The Bulge was the last major action the twins fought, although there was still much fighting right to the very end. Tom remembers seeing a twelve-year-old German soldier during the last weeks of the war. He’s got a photo of him. ‘Most of the time you never knew who you was fighting against,’ he says, but claims he never felt any great animosity towards the Germans. Nor did Dee. ‘At the end, they just wanted to get away from the Russians,’ he says. ‘We wasn’t their enemy. The Russians was their enemy.’

When VE Day finally arrived, the twins were in Czechoslovakia. The Americans told everyone in the town to turn their lights on so that the German troops still up in the hills would know that the fighting was over. ‘I guess they got that signal,’ says Tom, ‘because the next day they were coming home in droves.’

They got to celebrate the war’s end a short while later. Earlier, they’d passed through Bonn and had found a cellar full of wine and even whisky. Backing up an army lorry, they had helped load the drink onto the back. ‘Boys,’ the officer in charge had told them, ‘when the war’s over, you’ll get all this.’ Neither Dee nor Tom believed a word of it. But once the fighting was over, they pulled back to a bivouac area and lo and behold, there was the lorry still full of the drink. ‘So they was good as their word,’ says Dee. They all had a skinful that day. ‘We was glad it was over,’ says Tom. ‘Of course we were.’

A month later, they were heading home. The war in the Pacific might not have quite been over, but after three invasions and fighting through Africa, Sicily, France, Belgium, Germany and Czechoslovakia, the Bowles twins had more than done their bit. The army was happy to let them go and get on with the rest of their lives.

In May 2005, Tom and Dee came back to Europe for the first time since the war. I’d first met them eighteen months before, at Dee’s place in northwest Alabama, and even then I was struck by their laidback, easy-going approach to life. They seemed pleased that someone was interested in their wartime experiences, but when I asked them whether they had ever been back to Normandy they said no, they’d not thought about it too much. And do you think you might some time? I asked. They looked at each other and shrugged. ‘I don’t know about that,’ said Dee. ‘Tom’s son Tim has been talking about it for a while, but I’m not so sure …’

Tom lives in Lake Charles, Louisiana, but since his wife passed away he’s been spending more time with his brother and sister-in-law. They’re as close as they ever were and it’s still almost impossible to tell them apart, even now that they’re both in their eighties. When they came back, I wondered, after the war, did they ever talk about their experiences as soldiers? No, came the answer, hardly ever. ‘We just forgot about it,’ said Dee. ‘We talked more about before the war, growing up and stuff.’ Instead, like millions of others, they simply came back and got on with their lives. They learnt a trade and became electricians. Dee married and had two daughters, Tom married and had five boys. Most of the boys became electricians too, all except Tim, the youngest. He works in IT.

Then in 1994, there was a notice in the local newspaper in Lake Charles. The fiftieth anniversary of D-Day was approaching and veterans were being asked for their memories. Tom called them and a reporter came out to talk to him, wanting to know about his war record and how he came to get two bronze stars. It was the first time Tom had thought about it in years; he hadn’t even got his medals. He’d never bothered; nor had Dee.

They began to realize there weren’t so very many of them left and started thinking it might be a good idea to get some of their memories down for their children and grandchildren. They ordered their medals, joined the Big Red One Association and got in touch with a few of their former comrades-in-arms. In 2000, the D-Day Museum in New Orleans opened, and the twins went down there with their families and joined a parade with other veterans.

Sometime after I’d visited them, Tim finally persuaded them to make the pilgrimage, and so in May 2004, a couple of weeks before the sixtieth anniversary celebrations began in France, the men of the family – Tom and Dee, and Tom’s five sons – flew over to England. It was the first time the twins had ever been in an aeroplane and their first time out of the United States since returning after the end of the war.

Since I live not so very far from their old camp near Broadmayne, I had been to the New Inn in West Knighton and had sent Tom and Dee a photograph of the pub, and so now, on this visit, they naturally wanted to see the place again for themselves. They called in at my house, then together we all drove down towards Dorchester. It was a warm and sunny May day, just as it had been when the twins had taken their picture at the pub, a couple of weeks before D-Day. The roads narrowed as we drew closer, the hedgerows rising and bursting with green. Then there we were, pulling into the courtyard, opposite the front of the pub. It’s remarkably unchanged on the outside, still instantly recognizable from the black and white picture taken all those years before. The twins got themselves a beer then posed outside for a new set of photographs. Watching it was a profoundly moving experience. It seemed incredible to me that sixty years before, two young men had stood there – unknowing – on the eve of one of the most significant moments in world history and yet now, with the world such a different place, here they were again. It was very humbling.

VILLAGE PEOPLE (#ulink_5c7c1e7b-b101-58f4-9a98-55a82a552f04)

Dr Chris Brown (#ulink_e5321811-da0e-5928-bb09-1ee846371688)

Growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, I was certainly very conscious of ‘The War’, and like many boys at that time, I made model Spitfires and Tiger tanks and read Commando comics. Grown-ups rarely talked about it, but they did often refer to it, although usually as a means of implying that we younger generation did not know how lucky we were – which I suppose was true. My mother, for example, would mention the war in the context of food. If I ever took too much butter for my bread, she would say, ‘That’s enough to have lasted a week in the war!’

What I never bothered to consider, however, was that most men I knew who were then in their fifties and sixties had probably served during the war, and that everyone I knew of that age had lived through it. The only person I knew who was happy to talk about it at length was the Classics master at school, who used to regale us with tales of the war in Burma. ‘Did you kill any Japs, sir?’ we would repeatedly ask him, then rush off to re-enact our own version of jungle warfare in the trees and bushes at the bottom of the playing fields.

One person who certainly kept his war record pretty quiet was the village GP, Dr Brown. Like most young children, I was forever coming down with stomach bugs, chest infections or needing stitches, so I knew him better than most other adults in the village, and was as familiar with the inside of his surgery, with its green waiting-room chairs and smell of antiseptic, as any place outside my own home.

Dr Brown was truly a pillar of the community. Kind, with a gentle, soothing voice and a warm smile, he did so much more for the village than tend the sick, whether it be helping with the various village sports clubs, writing a musical (revived every ten years), or allowing the villagers to use his swimming pool. Just a short walk down the road from my childhood home, his pool was where I learnt to swim.

But I never thought of Dr Brown in any other light. I liked him enormously, but to me he was simply the village GP and that was that. Only many years later, however, did I discover that he had served with the Chindits in Burma. His wife lent me his wartime diary, and for a moment I was quite taken aback as she handed me the thick exercise book, with its homemade brown wrapping paper dust jacket. Within its pages, neatly written up in blue ink, were his remarkably detailed – and human – wartime jottings, as well as a number of newspaper cuttings and photographs. The Chindits were the stuff of wartime legend; it seemed strange that the man I remembered had been part of that special force of jungle warriors.

Many myths have grown about the Chindits. The romance and derring-do of these soldiers are often all most people know about the war in Burma, and to many they are still seen as the SAS of the jungle war, the ‘green ghosts that haunted the Jap’. Like the SAS, they operated deep behind enemy lines, but there the similarity ends. The SAS were a small band of men, but the Chindits, although also special forces, were made up from ordinary infantry brigades; nearly 10,000 troops took part in the Second Chindit Expedition in 1944.

They were the brainchild of Major-General Orde Wingate, a charismatic and unorthodox soldier who had been brought to the Far East in 1942 by General (and soon to be Field Marshal) Wavell, then Commander-in-Chief of India. The war against Japan was not going well: Singapore and Malaya had been lost and so had much of Burma. With the Japanese knocking on the door of India itself, Wavell decided he needed someone with fresh ideas, unconstrained by notions of military orthodoxy, to help plan the reconquest of Burma and at the very least inflict serious damage on the Japanese lines of communication. He had first met Wingate in 1938, during his time as C-in-C Middle East, and found him to be a mercurial officer with plenty of energy and determination. Wavell’s early impressions were not misconceived. In 1941, and with only a few hundred men, Wingate famously bluffed 12,000 Italians into surrender during the Abyssinian campaign.

Wingate arrived in India having recovered from a recent suicide attempt. A manic depressive, he nonetheless found himself re-energized by the task Wavell had given him, and after reconnoitring northern Burma, began developing his ideas for ‘Long-Range Penetration’ (LRP). Mistrustful of paratroopers, he nonetheless believed that with the help of supply drops from the air directed by radio on the ground, it should be possible to maintain a force that could operate within the ‘heart of the enemy’s military machine’. His theory was that by keeping constantly mobile, his forces could avoid facing any concentration of enemy forces.

Wavell gave the go-ahead for an expedition using the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade. Split into seven different columns, they set off in February 1943, managing to penetrate 150 miles behind enemy lines. They blew up sections of railway, gathered some helpful intelligence and to a certain degree distracted the Japanese, but as one battalion history put it, ‘Never have so many marched for so little.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Strategically, the expedition was certainly of small value, while the many who became sick or were wounded along the way had to be left where they were – a horrible fate considering the brutality with which the Japanese treated such men.

The First Chindit Expedition was, however, a propaganda dream, and Wingate and ‘The British Ghost Army’ were fêted around the world in the Allied press. Crucially, Wingate had also come to the attention of the prime minister, Winston Churchill – so much so that he was called to Canada to outline his ideas on Long-Range Penetration at the Quebec Conference in August 1943, a gathering that was attended by Churchill, President Roosevelt and the British and American Chiefs of Staff. An impressive orator, Wingate persuaded the Combined Chiefs of the value of launching another expedition. Even the Americans agreed to it, for although they had no interest in Britain’s colonial empire, they were keen to help the Chinese, who they believed could make a difference in the war against Japan. They had already sent troops under General Joe Stilwell to lead the Chinese Nationalists operating on the border of northern Burma. With this in mind, Wingate was given the task of cutting the lines of communication to those Japanese forces opposing Stilwell’s men. Wingate agreed, although privately he also hoped to reconquer the whole of the north of Burma.

Wingate also achieved another coup when the American Chief of the Air Staff, General ‘Hap’ Arnold, offered to lend him an air force of transport planes, gliders, fighters and bombers, to support the expedition. This was to be called No 1 Air Commando, or ‘Cochran’s Flying Circus’ after its commander, Colonel Phil Cochran. This generosity from Arnold enabled Wingate to think on an even bigger scale. With comprehensive air support, his men would not be left to fend for themselves; furthermore, they could be flown deep behind enemy lines to start with rather than tramping hundreds of miles through thick jungle. With air support, it would be possible to maintain many more men, and with many more men, the effectiveness of the Chindits would be even greater. That was the theory, at any rate.

Like many others, Captain Dr Chris Brown had been impressed by the accounts and coverage of the Chindits’ exploits, so when he saw a request for volunteers for a further expedition, he decided to put his name forward. ‘I could never face my conscience again,’ he wrote in a letter to his parents, ‘if I didn’t do something about it.’ A young doctor in the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC), he spent a fortnight assigned to the 4/9 Gurkhas, before joining the 2nd Battalion, the King’s Own Royal Rifles, at Dukwan Dam, near Jhansi in India, on 1 December, 1943.

Part of the 111th Indian Infantry Brigade, the battalion left Dukwan by special train on 15 January 1944, crossing into Assam six days later. From the railhead at Silchar, they had to march across country to Imphal on the India – Burma border where they were to begin training. A taste of things to come, it was tough going, but Chris was fit and young, and as a boy growing up in Scotland, had always loved mountains and the outdoor life. On a morning of rain and mist – ‘Scottish weather’ – his first view of Imphal Plain reminded him of Rannoch Moor. Imphal itself, he noted, was ‘no more than a glorified village, tho’ at present it is the main military base, and there is a constant and staggering flow of trucks.’

Amidst this hive of activity, they began their preparations. As with the first expedition, the main fighting unit was to be the ‘column’, which was formed by splitting a battalion of roughly 800 men, such as the 2nd King’s Own Royal Regiment, into two, and then adding a number of mules, ponies and bullocks. Each column had its share of rifle platoons, mortars, engineers, reconnaissance, and, of course, medical staff, albeit just one doctor and four medical orderlies. The 2nd King’s Own was divided into 41 and 46 Columns; Chris was assigned to the latter.

Training principally involved getting fit and practising marching through thick and often precipitous jungle, and crossing rivers. Getting men across water was not usually too much of a problem – it was persuading the mules that was tricky, and ensuring that none of the equipment became wet and damaged in the process.

General Wingate himself visited the brigade and inspected their progress in February, just a few weeks before the expedition was due to be launched. ‘We watched his arrival in a light plane with some awe,’ noted Chris. ‘[He was] a small figure in a pale khaki suit and an enormous old-fashioned topee.’ That evening, Wingate held a conference for all the brigade officers – Chris included – in which he outlined his plans. Nearly 9000 men would be used for the Second Chindit Expedition, he explained, initially made up from five infantry brigades of which 111th Brigade was one. As a deception, they were to be called the fictitious ‘3rd Indian Division’. Formally, they were ‘Special Force’; informally, they were simply Chindits, a name derived from Chinthé, the name of the mythical griffins that were supposed to guard Burmese temples.