По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

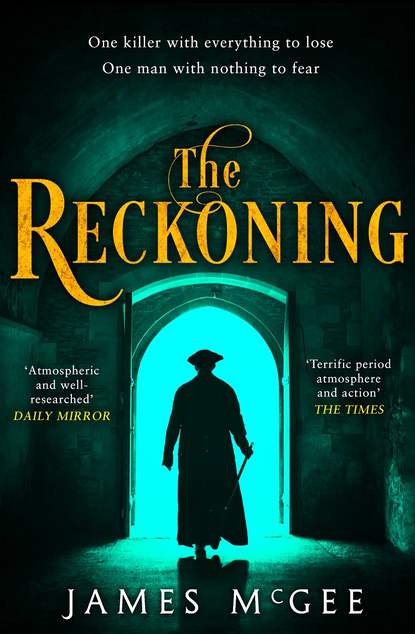

The Reckoning

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Jago snorted. “You expect me to answer that?”

Hawkwood smiled thinly.

“Suit yourself,’ Jago said. “But if I were you, I wouldn’t go talkingto any strange women.”

“In case you’ve forgotten, that’s the sole purpose of my visit.”

Jago winked and took a sip from his glass.

“By the way,” Hawkwood said, “in all that excitement, I forgot to ask: did you and Connie ever buy yourselves that carriage?”

“Carriage?” Jago blinked at the sudden change of subject.

“I’ll take that as a no, then. What happened? Before I went away, you were thinking of buying a horse and gig so that you and Connie could ride around Hyde Park and mix with the swells.”

“Ah, that.” Jago stared at him. “Remind me again; how long is it you’ve been gone?”

“Three months.”

“Well, that explains it.”

“You mean there was a change of plan?”

“Not certain there ever was a plan, as such; more like a bloody stupid idea.” The former sergeant smiled ruefully. “Be honest, can you see me and Connie swannin’ round the park in a carriage?”

“Connie, maybe,” Hawkwood said. “Not you.”

“I’ll tell her you said that, she’ll be tickled pink.” Jago frowned. “What made you think about Connie and carriages?”

Hawkwood did not reply.

“What, you getting maudlin in your old age?” Jago asked. Then his chin lifted. “Ah, don’t tell me; you and Maddie had words? Is that it?” Jago nodded to himself as if everything had suddenly been made clear, then tilted his head enquiringly. “What’d she say when you got back?”

“Not a hell of a lot,” Hawkwood said.

Maddie was Maddie Teague, landlady of the Blackbird tavern. Three months before, when Hawkwood had been preparing to leave for France with no expectation of an imminent return, Maddie had asked him if she should keep his room. Her green eyes had transfixed him when she’d posed the question. She’d tried to make light of her enquiry, telling him it had been made in jest, but he’d read the concern in her face and her genuine fear for his safety.

Hawkwood had smiled and told her that she should keep the room, but they’d both known there was no guarantee that he’d make it back. Despite that, there had been no whispered endearments, no lingering embrace. Instead, Maddie had stepped close and tapped his chest with her closed fist before resting her palm across his cheek. She had then asked him how long she should wait for news.

“You’ll know,” Hawkwood had told her.

“Then don’t expect me to cry myself to sleep,” she’d retorted, but she had not been able to hide the catch in her voice.

It had been a cold and damp morning when the mail coach deposited Hawkwood at the Saracen’s Head in Snow Hill. The 270-mile journey from Falmouth had taken four days. If he’d travelled by regular means it would have taken a week. It was the same route by which the news of Nelson’s death at Trafalgar had been conveyed to the Admiralty by Lieutenant Lapenotière, commander of the schooner HMS Pickle; or so Hawkwood had been informed by the clerk at the Falmouth coaching office. Lapenotière had supposedly made the journey by post-chaise in thirty-eight hours. Having no urgent dispatches to deliver, Hawkwood had been forced to settle for a slower ride. When he alighted from the un-sprung coach for the last time, it had felt as if his back had been stretched by the Inquisition. He wondered if Lapenotière had suffered from the same discomfort.

The Blackbird lay in a quiet mews off Water Lane, a stone’s lob from the Inner Temple. It was a short walk from the Saracen’s Head and the route had taken him down through the Fleet Market. It had felt strange, making his way past the shops and stalls, because even at that hour of the day they were crowded and after being surrounded by wide open seas and even wider skies during the crossing from America, the hustle and bustle of London’s congested streets, while instantly familiar, had come as something of a shock, as had the smells. After the clean air of New York State’s lakes and mountains and the bracing bite of the North Atlantic winds, he’d forgotten how much the city reeked. At the same time, it felt as though he’d never been away.

The Blackbird’s door had been open, in readiness for the breakfast trade. Maddie’s back had been to him. Her auburn hair tied in place with a blue ribbon, she’d been directing the serving girls as they’d flitted between the tables and the kitchen, taking and delivering orders. Hawkwood had waited until Maddie was alone before he’d enquired from behind with a weary voice if there were any rooms to be had. Maddie had turned to answer, whereupon her breath had caught in her throat and her eyes had widened.

The sound of her palm whipping across his left cheek had been almost as loud as a pistol shot. Breakfast diners within range had looked up and gaped; more than a few had grinned.

Hawkwood hadn’t moved as the burning sensation spread across his face.

Maddie Teague had stared up at him, her eyes blazing. Then, as quickly as it had flared, the anger left her and her face had softened.

“You could have written,” she said.

“On the bright side,” Jago said, chuckling. “She could’ve been carryin’ a bowl of hot broth or a carvin’ knife.”

“Lucky for me,” Hawkwood said.

“You made up, though, right? She didn’t stay mad?”

“No,” Hawkwood conceded. “She didn’t.”

“There you go then.” There was a pause before Jago added, “She asked if I’d heard from you.”

Hawkwood stared at him. “She never mentioned that.”

“Sent me a message. I called round; told her I hadn’t heard but I’d make enquiries.”

“That’s when you went to see Magistrate Read.”

“It was. He told me that, as far as he knew, you were still alive and that if anything did happen, he’d get word to me.”

“And you’d pass the word to Maddie.”

Jago nodded.

“She was angry,” Hawkwood said.

“Women are funny like that,” Jago replied sagely. “I told her not to worry; that no news was good news. Can’t say she was convinced. Think she was all right for the first month. After that …” Jago shrugged and then brightened. “I did put in a bid. Told her if anythin’ were to ’appen, and if she had trouble makin’ ends meet, I wanted first refusal on your Baker.”

“That was gallant. How did she take it?”

“Not well. Told me I’d have to join the bloody queue.” Jago’s face turned serious. “You do know that, if you hadn’t turned up, she’d have waited. There’s no one else. There’s plenty who’d like to step up but, until she heard otherwise, it’d be you she’d be holdin’ out for.”

“I told her she’d know if anything had happened,” Hawkwood said.

“Reckon we both would,” Jago said sombrely, and then he grinned once more. “So I’d still be in the queue for your bloody rifle. I’d raise a glass, too, though, for old time’s sake. You can count on that.”

“I’m touched,” Hawkwood said.

“Aye, well, you’d do the same for me, right?”

“Depends,” Hawkwood said.

“On what?”