По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

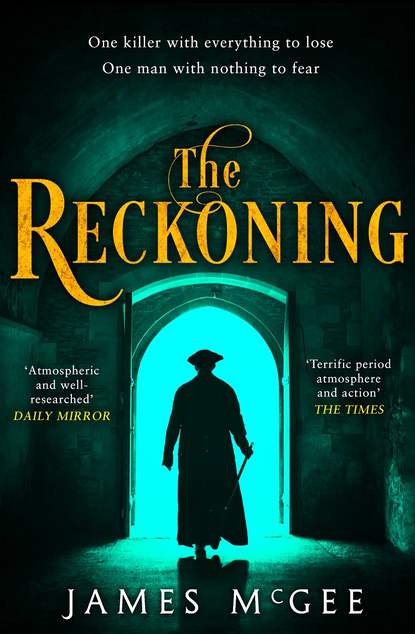

The Reckoning

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Her chin lifted. Then, fixing him with a conciliatory look, she said, “And it is your task to discover who was responsible?”

“It is.”

She nodded. “Could the perpetrator strike again?”

“It’s possible, yes.”

“So until you find him, we are all of us at risk.”

“I can’t say you won’t be. We don’t yet know his motive.”

“You’re saying she could have been killed for who she was, rather than for what you think she was?”

“Yes.”

“And a rose is not an uncommon adornment. She could just as easily be a washerwoman as a whore.”

“She could.”

Her eyes clouded. In that instant Hawkwood caught his second glimpse of the woman behind the mask; a woman who, by force of will, had managed to haul herself out of the gutter and into the privileged ranks of society, all the while knowing and resenting the fact that there were elements of her previous life still buried deep within her that she would never be able to erase.

There was fear there, too, he suspected; fear that, one day, someone would confront her and remind her of her former existence. It was the most vulnerable chink in her armour and she was wondering if this was the moment that weakness was about to be exploited. The sudden flare in her eyes was a warning sign that she would defend her reputation to the hilt if she felt it was about to be challenged.

“Which is why we need to confirm her identity,” Hawkwood said, and watched as the fire died away.

“Because, whatever their reasoning, the sooner you find the person who killed her, the safer we all will be?”

“Yes.”

“Then I am sorry I’ve kept you from your task and that your journey here has been wasted.”

“Not at all. All enquiries are useful.”

Acknowledging Hawkwood’s response with a small – possibly appreciative – nod, she said, “I will, of course, enquire of my ladies if they have heard of or know of anything that could assist your investigation.”

“That would be most helpful. Thank you.”

“It is the least I can do.” She paused again and said, “And if I should come into possession of information which might be relevant, how may I notify you?”

“Through Bow Street Magistrate’s Court.”

“Yes, of course.”

As if in need of some activity to fill the subsequent pause in the conversation, she retrieved her cup and took an exploratory sip. Finding the brew had grown cold, she wrinkled her nose and returned both cup and saucer to the tray, leaving a faint smear of pink lip salve along the cup’s rim.

Hawkwood judged this the opportune moment to take his leave, but as he turned to go she said suddenly, “When Thomas announced you were from the Public Office, I confess, you are not what I was expecting. I apologize if my manner was less than courteous. You are a Principal Officer … what they call a Runner, yes?”

Hawkwood wondered where this was going. “We prefer the former, but yes.”

She permitted herself a smile. “Duly noted. It has been my experience that most Public Office employees look incapable of breaking into a brisk walk, let alone a run, whereas you look, if I may say so, rather more … capable. You have the air of a military man. Would I be right in thinking you have fought in the service of the king?”

“I was in the army.”

“I thought as much. I made a small wager with myself when I saw the scars on your face and the cut of your coat. It is military-issue, is it not?”

“It is.”

“You look surprised. Did you think I was uninformed about such matters? If I were to name every colonel who sought sanctuary within these walls, we would be here until Easter. I believe I could also name not only every regiment in the British Army, but every fourth-rater in his majesty’s navy, given the number of admirals that have raised their flags in my establishment. Not to mention magistrates, ambassadors, assorted aristocrats, clergymen and all but two of Lord Liverpool’s cabinet. You were an officer, yes?”

Hawkwood didn’t get a chance to respond.

The smile remained in place. “In this profession, if you learn one thing, it is how to read men. Your attire betrays you. Your outer wear may have seen better days, but your boots are of good quality, as are your jacket and your waistcoat, from what I can see of them. It is also in the way you carry yourself.”

The blue eyes narrowed. “You would not have moved from colonel to constable – my apologies, to Principal Officer. That would be too far a step down, I think. Too old for a lieutenant, so you were either a captain or a major.”

Tilting her head, she went on: “You look like a man who is used to command and yet you have little respect for authority. I suspect you came up through the ranks and proved yourself in some engagement, therefore I choose the former. You were a captain. Am I right?”

“And there was I, thinking I hadn’t made a good impression,” Hawkwood said.

The frown returned. “Yes, well, in that you are not wrong. Your manners could certainly use improvement. An officer you may have been, but you display the attitude of a ruffian. Has anyone ever told you that?”

“Once or twice.”

“Or perhaps it is a deliberate strategy, like the employment of sarcasm,” she countered tartly.

“It comes in useful when I don’t have a pistol to hand.”

Unexpectedly, the corner of her mouth dimpled once more and her gaze moved towards the clock on the mantelpiece. Turning back, she said, “Yes, well, unfortunately, much as I’ve enjoyed our conversation, I see time is against us. I have an evening’s entertainment to arrange, so you must forgive me.” She gazed at him beguilingly. “Unless there is anything else you wish to ask?”

“Not at this time. I may need to call on you again at some date.”

She inclined her head. “Of course.”

Hawkwood was about to turn for the door, when she said quietly, “I think, perhaps, I should like that. Despite your questionable manner and the reason for your visit with all this talk of graveyards and murder, you have enlivened what would otherwise have been an exceedingly dull afternoon.”

Her eyes held his. “I have the distinct feeling that there is more to you, Captain Hawkwood, than meets the eye. I suspect that, were I to scratch the surface, I would unearth all manner of interesting truths. Why is that, do you suppose?”

“I have no idea,” Hawkwood said, “though, curiously, I was thinking exactly the same thing about you.”

She continued to regard him coolly for several seconds. “Then, perhaps, if your investigation allows, you might consider visiting in a more … private capacity?”

“On my salary? I doubt it.”

“Then you do yourself a disservice. Attendance is not solely dependent on the depth of one’s purse. If you were to attend, it would be at my invitation.”

She let the inference hang in the air between them.

“I wouldn’t want to lower the tone,” Hawkwood said.