По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

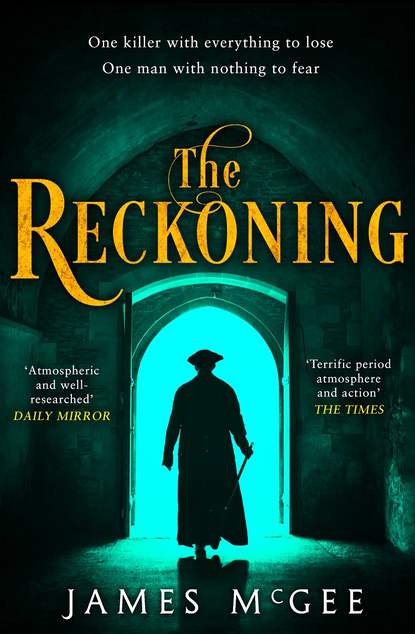

The Reckoning

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“There could be more of them.”

“Wouldn’t surprise me. The buggers breed like rats. I’ll cross that bridge when I come to it.”

“Be interesting to know how they came by the guns,” Hawkwood said, eyeing the three blunderbusses that were taking up space at the other end of the table. “These look like Post Office issue.”

“You askin’ as a police officer or a concerned citizen?”

“Both.”

The blunderbuss was the weapon of choice for mail coach guards, who were the only Post Office employees allowed to carry firearms. Designed to protect the cargo from interception by highwaymen, they had served their purpose well. There hadn’t been a serious attack on a mail coach for more than two decades.

“Money talks,” Jago said. “How many villains you know have been caught carryin’ an army- or navy-issue pistol? Bloody ’undreds, I should think. Scatterguns ain’t that hard to get hold of, you know the right person.”

“And you’d know that how?” Hawkwood said.

Jago grinned and tapped his nose with his left forefinger and then said, “Shit!” as another bit of gravel was extracted and dropped on to the plate.

Hawkwood counted them up. Five tiny olive-pit-sized fragments occupied the platter, while a couple of puncture wounds had yet to be probed.

Still, he thought, Jago had been lucky.

“You were lucky,” Hawkwood said.

Jago looked up at him. “Really? An’ how do you work that out?”

“You’re still here. You should be as dead as Shaughnessy, the range he fired from. I’m wondering if his powder was damp. Either that or it was low quality.”

“Tell that to the bloody window,” Jago said. “From where I was standin’, I’d say it was dry enough.”

“Nah, your man’s right. The bastard should’ve taken your head off. Good job you moved when you did.” Del, who’d arrived back with Ned, jabbed a thumb at Declan Shaughnessy’s lifeless corpse. “Else you’d’ve ended up like ’is nibs.”

“You’re a real comfort, Del,” Ned said. “Anyone ever tell you that?”

“Only your missus,” Del retorted, grinning.

“There,” the physician announced. “Done – or as far as I can tell.” Putting down the tweezers, he cut off a length of lint. Taking one of the vials, he removed the stopper, soaked the lint with the contents and proceeded to dab the wounds, much to his patient’s further discomfort.

“Keep the area as clean as possible. If the wounds become inflamed, you know where to find me or else get another doctor to take a look. I’ve done the best I can but I may not have got them all.”

Using the rest of the lint, the physician began to fashion a bandage around Jago’s shoulder. His hands, Hawkwood saw, were now perfectly steady and the dressing was expertly applied. Roper was clearly no quack. The man may have lost his standing among his former peers and patients and been ostracized by the more reputable areas of society, but from what Hawkwood had seen, if he was now using his medical skills to aid the less fortunate in London’s back streets, the people of the rookery were lucky to have him.

Hawkwood watched as the physician restored his equipment to his bag before moving to attend to those customers who’d been caught in the crossfire. Thankfully, there weren’t many. Serious peripheral wounds had been prevented as most people had used the tables and furniture as cover. The majority of the injured were suffering from the effects of flying splinters and glass fragments rather than gravel pellets.

The landlord, a dour-looking character whom Jago had addressed as Bram, was already nailing boards over the broken window. He’d looked ready to take someone’s head off when he’d first inspected the damage, but a look from Jago and a promise of financial restitution had cooled his ire, as had an immediate contribution to the restoration fund following a search of the dead men’s pockets.

Jago grimaced as he eased his shirt back over his shoulder. “Wounds, my arse. Pin pricks more like. Typical bloody bog trotter. Had me in his sights and he still cocked it up.”

“Got the drop on Jasper, though,” Ned said, grinning. He lifted his chin. “Come on, Del. It’s Declan’s turn for the cart, and don’t forget his bloody hat.”

“Like you’d’ve fared any better,” Jasper countered. “Bastard crept up on me when I was takin’ a piss. I was distracted.” He watched as Del and Ned rearranged Declan’s ragged corpse into a manageable position for carriage before looking contritely towards Jago. “Sorry, big man; my fault they got up here.”

Jago shook his head. “Could’ve happened to any of us.”

“Not you,” Del said as he took hold of Declan’s right ankle. “If it’d been you in the pisser, he’d’ve shot you where you stood. You’d be dead and we’d be none the wiser as to who’d done it.”

“An’ you’d have split my winnings between you,” Jago said. “Right?”

Del grinned. “Too right. No sense in letting all that spare change go to waste.”

“Bastards,” Jago said, but without malice, as Ned and Del began to manhandle the second Shaughnessy brother towards the back stairwell.

“What’ll you do with the bodies?” Hawkwood asked.

Jago shrugged. “Give ’em to the night-soil men. Either that or feed ’em to Reilly’s hogs.”

Jago wasn’t joking about the hogs. Even though they sounded like something out of a children’s fairy tale, along with wicked witches, ogres and fire-breathing dragons, the animals were real. Reilly, a slaughterman with premises off Hosier Lane, housed the things in a pen at the rear of his yard, where, it was said, they were kept infrequently fed in anticipation of a time when their services might be required.

It was a prime, albeit extreme, example of the type of self-efficiency employed by the denizens of the rookery who over the years had devised their own unique methods for settling disputes and disposing of their dead. Admittedly, it was a practice frowned upon by law, but on this occasion, looking on the positive side, it did eliminate the need for an official report on the altercation.

A dull thudding sound came from the stairs. Hawkwood presumed it was what was left of Declan’s skull making contact with the treads as his remains were transported down.

Micah returned to the table. “Night-soil men said they’ll take them. They wanted the money up front.”

“You took care of it?”

Micah nodded. “They’re waiting on the last one.”

As if on cue, Del and Ned reappeared and moved to the third body, which was still lying at the top of the taproom stairs.

“Hope Bram’s got plenty of shavings,” Del muttered. “Makin’ a hell of a mess of ’is floor.”

Ned looked at him askance. “How can you tell? Years I’ve been coming ’ere, it always looks like this.”

“Just makin’ conversation,” Del said. “You ready?”

“Wait,” Hawkwood said. Kneeling, he withdrew the stiletto from the ruined throat.

“Wouldn’t want to forget that, would we?” Jago said sardonically as Hawkwood wiped the blade on the corpse’s sleeve before returning the knife to his right boot. “All right, lads. Carry on.”

Ned nodded to his companion and then caught Jasper’s eye as they set off towards the stairs, the body sagging between them. “Get ’em in, old son. We’re going to need something strong after this. And don’t give me that look. It’s still your bloody round. We ain’t forgotten.”

“Should’ve got the night-soil lads to do the liftin’ and carryin’,” Jasper grated.

“Then what’d the smell be like?” Del said, over his shoulder. “Don’t want them tramping their shit all over the floor as well. It’s bad enough as it is.”

“Jesus, it’s like listenin’ to a bunch of bloody fishwives,” said Jago. “If I’d wanted this much witterin’, I’d’ve gone to Billingsgate. Just load the damned things on to the cart. The sooner they’re off the premises and headin’ downriver, the better I’ll feel. And you, Jasper, get the drinks in; else I may decide they can take you with them. You’d make good ballast.”

Turning to Hawkwood, he shook his head in resignation. “Swear to God, it’s like herdin’ cats.” Buttoning his shirt, he eased himself into a comfortable position. “Right, that’s the formalities over. I take it you’re ready for a wet?”