По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

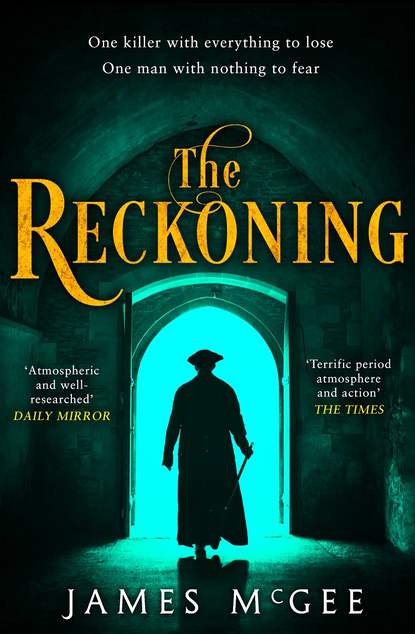

The Reckoning

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

For a moment it looked as though the gravedigger was about to offer further protest, but Hawkwood’s expression and tone of voice must have warned him that an argument was futile and might prove detrimental to his own health.

It was then that the wisdom of what he was about to do struck Hawkwood forcibly and he cursed his rashness. It was too late now, though, for he had no intention of giving Gulley the satisfaction of knowing he might be dealing with a police officer who’d just made what could well turn out be a very unwise decision. But as he caught the sexton’s eye, he was rewarded with a small, almost imperceptible nod of acknowledgement, or it might have been gratitude.

Over the constable’s shoulder, he saw that Dobbs was on his way back, pushing a flat, two-wheeled cart before him, the sacking folded on top. The cart’s wheels had become clogged with mud, making progress difficult. The older gravedigger, Hawkwood noted, could see that his assistant was struggling but made no attempt to assist. By the time the cart rolled to a halt, the apprentice was perspiring heavily.

Hawkwood addressed Gulley. “Your turn. Get down here – and mind where you step.”

The gravedigger’s knuckles whitened against the handle of his shovel.

“You won’t need that,” Hawkwood told him.

Sensing tension in the air, the constable went to step forward again.

Hawkwood, wondering what assistance Hopkins intended to offer while still holding his coat, waved him away.

It took a further ten minutes to scrape away the mud and, with Gulley taking the feet and Hawkwood the torso, and with the apprentice Dobbs helping to take the weight, lift the sack and its contents up and out of the grave, though it seemed more like a lifetime. The mud was reluctant to release its grip and by the time Hawkwood and the gravedigger were helped out of the pit, their boots and breeches were wet to the thigh and caked in clay. Hawkwood had also been uncomfortably aware of the ominous creaking sounds that had come from beneath his and the gravedigger’s feet as they’d taken the weight of the corpse between them. It had been with great relief that he had stepped back on to solid ground.

“I want her delivered to the dead house at Christ’s Hospital,” Hawkwood instructed as the cadaver was placed on the cart and covered with the dry sacking.

“You know it?”

The constable nodded.

“For the attention of Surgeon Quill. He’s to expect me later.”

“Yes, Captain.”

“Good.” Hawkwood took back his coat, but did not put it on. “Dobbs can assist. Make sure the body’s covered at all times. I’m probably in enough trouble as it is; God forbid an arm should come loose and frighten the horses.”

Hawkwood knew that wasn’t likely to happen, but having the two men watch over their gruesome load was one way of ensuring it would arrive safely. The other reason for the precaution was that during the excavation it had become obvious that inside the sack the corpse was naked. A clothed cadaver being carted through the streets was bad enough. The ramifications, if the state of this one ever came to light, didn’t bear thinking about.

“You can’t do that!” Gulley protested.

Hawkwood spun back. “Of course I bloody can! I can do anything I want. I can even leave you in the damned hole if you don’t stop whining.”

Gulley bristled. “But there’s graves to dig!”

“Then do your own bloody digging! You’ve got a shovel. It’s not hard. You hold it at the thin end and use the other end to move the dirt.”

Gulley coloured under the onslaught.

Ignoring him, Hawkwood addressed the constable. “What the hell are you waiting for? Go.”

Jerked into activity, Hopkins swallowed and called Dobbs to him. As the cart trundled away, Hawkwood turned to the sexton. “When’s the funeral party due?”

The sexton drew a pocket watch from his jacket. “Not for an hour, yet.”

“Then you’ve time to make the site presentable?”

The sexton gazed about him. “Aye, reckon so.” He looked down at Hawkwood’s muddy forearms and clay-covered boots and breeches, and jerked his chin towards the cottage and the smoke curling up above the black-slate roof. “Got hot water on the fire, if’n you want to clean up.”

Hawkwood considered the filth on his hands and the activity they’d been engaged in. “It’s a kind offer, Mr Stubbs. I’m obliged.”

The sexton nodded. To the hovering Gulley, who’d retrieved his shovel and was holding it across his chest as if he was about to defend an attack on a bridge, he said, “I’ll be back soon as me and the officer here have concluded our business. Smartly now, Solomon, if you please. Don’t want to keep the widow waitin’.”

Before Gulley could reply, the sexton gestured to Hawkwood. “This way.”

Hawkwood was not surprised to find the interior of the cottage was as tidy as a barracks. Not that there was much to it. The ground floor consisted of a single room which served as both parlour and kitchen. The furniture was plain and functional. There was an oak table, a bench and small dresser in the cooking area and a settle that faced the open hearth, which was protected by a metal guard. The wall at the back of the hearth and the ceiling immediately above it was black with soot. Cord had been strung across the ceiling from which several threadbare shirts had been hung to dry. A set of stairs in one corner led to the first floor and the sexton’s no doubt equally neat sleeping quarters. Incongruously, a small writing desk sat against the wall opposite the fire. Above it was a shelf bearing half a dozen leather-bound volumes.

Asking Hawkwood to take a seat, the sexton poured hot water into a jug from a pot on the hearth and emptied the jug into a blue enamel basin which he placed on the table. A drying cloth and scrubbing brush were produced from a table drawer.

The basin had to be replenished twice, by which time Hawkwood had removed most of the dirt from his hands and arms and his skin was pink from the scrubbing. Cleaning the mud from his breeches and boots would have to wait.

The sexton took the basin outside and emptied it on to the ground. Returning, he set it on the dresser and from a cupboard beneath produced a flask and two battered tin mugs. Without asking, he poured a measure into each mug and handed one to Hawkwood.

“It’ll take away the taste of the pit.”

Hawkwood drank. Brandy: definitely not the good stuff, but the sexton was right. The smell of the grave had been so strong that by the time the body had been loaded on to the cart it did feel as though the back of his throat had become coated with the trench’s contents. Two swallows of the sexton’s brew and it felt as if his entire larynx had been cauterized. As cures went, it was eye-wateringly effective.

When his vocal cords had recovered from the shock, he asked the sexton if he’d heard or seen anything during the night.

Predictably, Stubbs shook his head. “Not a bloody thing. I tends to sleep right through. Might stir if a field battery was to open up by my ear, but that ain’t likely round these parts.”

And the rain would have covered most sounds, anyway, Hawkwood thought, as well as every other sign that might have pointed to whoever dumped the body in the pit. As for the place of entry, in retrospect it was ludicrous to think the corpse might have come from over the hospital wall, which meant access had either been made via the main gate or else the body had been carried over the dividing wall from the adjacent burial ground.

Which left him where? Maybe the body would provide the answer. Suddenly, Gulley’s argument was starting to make sense. Perhaps it would have been easier to have left the thing where it was.

The thing.

Dammit, he thought. Now I’m calling her that. He drained the mug.

Sexton Stubbs, he saw, was throwing him a speculative look.

“You’ve a question?” Hawkwood said.

The sexton hesitated then said, “Back there, the constable called you ‘Captain’. If’n you don’t mind me askin’, that mean you were an officer when you was in the Rifles?”

“Eventually,” Hawkwood said. “It didn’t last.”

The sexton turned the statement over in his mind. Emboldened by the cynical half-smile on Hawkwood’s face, he enquired cautiously, “You miss it?”

“The army?”

The sexton nodded.

“Sometimes,” Hawkwood admitted. “You?”

Hawkwood thought about the sexton’s admission when they were standing by the graveside. Stubbs had received his wound at Corunna. Hawkwood remembered Corunna; the epic retreat across northern Spain in appalling winter weather. Discipline had broken down, food had been scarce and the dead and wounded had been left by the roadside. When Moore’s army eventually reached the port, there was no sign of the transports that should have been there to carry them home. By the time the ships arrived, four days later, the French, under Marshal Soult, had caught up and the town was surrounded, forcing the British to take to the field.