По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

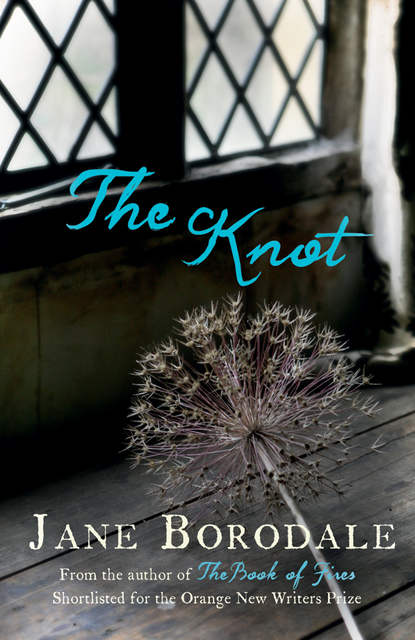

The Knot

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘No, now! Come at once! It is the end of April and you have not seen what has been happening out there,’ Henry makes himself laugh, tugs at her hand. And as they go out together to see the progress of the Knot and its surrounding borders, Henry begins a descriptive verbal tour for his wife, so that she can imagine how it is to grow. What will be here and here. What will be high, what will be climbing. He ignores Mote, who is grinning to himself as he listens to Henry’s enthusiastic, expansive rendition of how it is to be.

‘Picture its frankness,’ he entreats, ‘fat and green. Here will be the gillyflowers, and these little slips of lavender will have grown into plants by then, and see all these frondy bits of dill coming up, and these are the apothecary’s rose, and these the damask. What do you think?’

‘I do love roses.’ Her tone suggests that there is doubt involved in all of this.

‘The beehives are at the far end by the garden. If you sit up here by the house they will never bother you, and here is a good corner where the sun warms the wall. Even the little rock lizards bask in this spot.’

‘It really is quite hard to picture, Henry.’ He knows she is only allowing herself to see the mud, the parts that are not finished.

‘Think of a lily. Think of breathing in the plant’s waxy freshness like a draught of vital spirit.’

Frances does smile politely.

‘Think of a rose, then, think of bringing a fresh pink rose up to your face and drinking in its scent. It will have opened that morning and you will have your basket with you in order to gather many more, perhaps to make an aromatic water in your stillroom that very day while the blossoms are wholly fresh. If you like there could be a seat here for you to sit on, by the roses.’ He fetches a cask for her. ‘Try it!’

‘And my face won’t catch the sun?’

‘Your fair white skin would be shaded by the briars overhead.’

She looks suddenly keen. ‘And could we have that by the week in July when my mother comes to visit for my lying-in?’

‘Well, no, it may take a couple of years to reach overhead.’

She looks back at the house. ‘Everything takes so long. Can’t you just buy bigger roses, more full-grown, and get the men to twine them up as if they’d been there months and months?’

‘Roses do not like being moved – better to wait and coax them up the wires at their natural pace if you want them to last their proper lifetime’s span.’

Frances is becoming concerned for the state of her shoes and the mud that she will be treading into the house.

‘Every time I come out here, Henry,’ she points out. She knows perfectly well that one cannot rip up roses by the roots at whim. She is being wilful in her lack of interest. Henry cannot understand why she does not enjoy the garden more. To be sure there are many bare patches and places where herbs are not added yet, but he has described to her the wholeness of it, its beauty that by next June will surely dazzle her.

‘And is it all very costly, darling?’ she adds lightly. He looks at her. In the sunlight her straight black hair shines as though it is polished. She is not at all like a flower, he thinks. She is mineral, crystalline, waxy, brittle. The cost of his garden is not something that he wishes to discuss, he realizes.

‘How you can spend so much time inside the house without fresh air is quite beyond me,’ he retorts instead, as she walks away. He is very annoyed that she is blind to the garden’s soft growth, its promise. Mote smirks at the masterwort in the bed behind him, saying nothing.

He opens the garden door and leaves the neat, planned, incipient beauty of his Knot and strides off to inspect the orchards and the wilder, rampant plants in the wayside. He will clear his head, stretch his legs, shake off that disappointed feeling that comes from not being able to rouse enthusiasm in another being for something that one loves.

As he walks about, gradually and in truth for the first time in his life he begins to see the plants around him in terms of both their particularities and their potential. He begins to examine them all with a mounting respect and excitement for their distinctions, going from plant to plant, getting lost in their worlds, making mental notes, determined to write down what he’s observed when he returns to his study. Next time he will bring a notebook outside, and something to write with. He looks closely at the yellow loosestrife with its expanding, hairy, silky, fat stem, a plain-looking plant. He admires a specimen of elecampane; muscular in its softness, stiff with preparing to grow. He sees wild feverfew, with its almost sticky leaf; comfrey, a foot tall now, relaxing out of its growth into a soft almost reptile skin; and there is lady’s smock; pinkish, wavering in the air as though alert or tense. In the orchards the Dunster plum tree has rounded leaves peeping from the smooth twigs. On the greengage, tight waxy points are bright yellow-green, thin and strong. The apple leaves are opening raggedly on the branch like a conjuror’s flourish, and the quince is decked with little piles of hairy leaves, long pile like the hair on a young woman’s jawline. On the medlar are mild, elegant fingers of leaf and pinkish buds. Those leaves are fine in texture, rippled. He applies most observation to his favourites in the pear orchard. Their white blossoms are open like hats, and the leaves silver-soft, with a white-green tip that is crisp to the touch, and shedded brown husks at the base where it has sprouted. He watches a metallic green beetle clinging and clambering inside a blossom, and sees the boughs are dripping with mosses and crusted with three kinds of lichen; bearded, creeping, yellow. He wishes he knew more.

He wishes he could have some word from his father, who has kept up a resolute silence although Henry has written to share the good news about Frances’s condition. It is often surprising when a man gets what he hopes for, but so rarely does it come in a guise that one could have predicted. For a moment he has the most peculiar, overwhelming sensation that something vast is creeping up on him, drawing nearer. He turns around in alarm but it is only Blackie, trotting over the wet grass towards him, blunt tail in the air.

Chapter X.

Of BLOOD-STRANGE, or Mousetails. It floureth in Aprill, and the torches and seede is ripe in May, and shortly after the whole herb perisheth, so that in June yee shall not finde the dry or withered plant.

HE NEEDS TO GO AND COLLECT A HUNDRED ready-set slips of gillyflower, on order from Mistress Shaw, an old woman of some sixty years that lives in Wells. At its best her garden is a fat, colourful kerchief of blossom, and the children always vie to come with him in the cart when he goes to her for plants and seed. Rumour has it that as a young girl she was a Benedictine novice in a London convent, but that she left the calling and walked south-west long before the upheavals in the Church began. They say that she was never wed, yet everything else she plants springs eagerly to life.

Once they arrive at her garth, which is a square of land that sits beyond the town on the flat beyond the Bishop’s palace, Mary and Jane run off to hide and reappear later with the stains of strawberries about their mouths, oozing fistfuls of redcurrants, though they swear they were not thieving. She never chastises them, which he suspects is not only because their household provides good custom for her business. On occasion he has caught that raw, hungry glance that the barren can sometimes have on seeing children, but she seems to take some pleasure in cultivating their sound running full tilt in her garden.

She has narrow shoulders, but these days a protruding abdomen makes her very wide about the middle under her gown, and walking makes her lean a little as if one side of her were puckered up. Henry Lyte sees that she must suffer from some kind of growth inside her, but knows he cannot mention it unless she does. But on this visit, which is about his fourth or fifth already that season, as he is ducking out of the gate in her garden wall, he turns back to her. Checking that the garden boys are out of earshot, he asks very quietly, ‘You have been seen by a physician, madam?’

She looks down at her hands. The knuckles are shiny with the swelling of old age, and the nails green and split and grubby with work. When she speaks he smells her breath has the unmistakable unsavoury sweet smell of rot, and he is sorry for it.

‘There is no need, Master Lyte, no need at all.’

‘A doctor would give you physic to ease your suffering, and he can prepare you for what you might have to expect.’

‘I go to church to know what there is ahead of me. And beyond that I do not want to know. I pray. I try to sleep at night.’

‘Do you sleep easily?’

‘I do not.’

Henry tries to think what he can usefully do to help her. ‘I shall have a boy ride over with a bottle of aqua vitae for you, for the pain,’ he says.

Mistress Shaw’s eyes widen. ‘No! I can manage, thank you, Master Lyte.’

‘Or I can leave half a crown and you could order some yourself.’

‘No, really, but I thank you anyway.’

He smiles, will not be put off by her firm demurral. ‘I do insist,’ he says. And when he gets home he dispatches it immediately, a corked brown bottle wrapped in cloth.

But something very strange happens, which is that Mistress Shaw sends it back unopened with the boy that very evening, and with it is a little note. I thank you again Master Lyte, but I will not take strong drink. I hasten to assure you how this has naught to do with what they say of you, which wickedness I shall not believe.

What they say? Precisely what is it that they say? He must find out. He calls his bailiff but he is still out at market. He begins to asks Lisbet but before he reaches the crux she finds a pretence to vanish away to the kitchen. There is someone else he could ask, but something makes him hesitate. In the gloomy distance, he can see Mote’s form on the edge of the garden, digging, digging. He considers sending the boy to call him in. He delays lighting the candle, so that he can keep an eye on his progress. But in any event he does not need to make further enquiries, because by tomorrow forenoon a letter from his father comes.

Chapter XI.

Of HORSETAILE. It is good against the cough, the difficultie and paine of fetching breath, and against inward burstings, as Dioscorides and Plinie writeth.

HE IS NOT SURE WHICH IS WORSE, the fact that he has disappointed him, or believing that his father would allow himself to be manipulated into this position by that woman.

He stands, transfixed, in the hall. Across the passage he can hear Frances giggling in the kitchen over the clatter of pots. Her condition is softening her, she has begun to waddle very slightly as she moves from room to room, and listening now to her voice like that makes him feel protective. It suits her, this temporary relaxing of the rules she has set herself. He hears footsteps approaching from the kitchen, towards him standing there. The smile dies on her face.

Frances sees he has a letter in his hand. ‘What is it, Henry?’

‘From Sherborne.’ He is smarting.

Frances snatches the paper from him. ‘What does he say? I cannot make head nor tail of your father’s hand – it’s like cobwebs.’

‘Here.’ Henry directs her to the passage.

Her mouth opens a crack in disbelief as she takes it in.

‘How can he even suggest such a thing? And then seamlessly he goes on to talk of picking up the barley malt on Friday. It’s scarcely credible.’ Disparagingly she turns the paper to see if there is anything of worth to be found on the reverse. ‘This cannot warrant a reply,’ she says. ‘Do not even give him the pleasure of watching you put your attention to it.’

‘But does it sound like his usual way of speech?’