По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

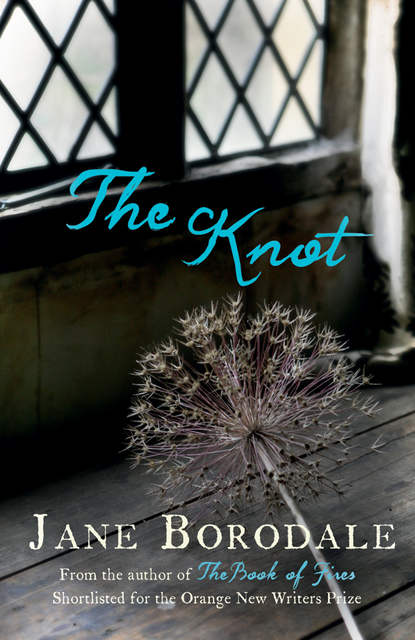

The Knot

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

No-one else seems to have heard what she said. What is the matter with everyone, are they deaf? And though he keeps on staring at her through the rest of the meal she does not speak again after that, and the conversation veers towards his father’s lawyer who is unwell. When they have finished eating Henry follows her down the corridor into the kitchen and closes the door.

‘Madam, did you mean to—’

‘Shhh.’ She puts her finger up to her lips and smiles, her eyes dancing.

‘That’s all you can say? You can’t leave a man unsure over something like that! I beg you!’

She touches his arm. ‘We’ll see. I am rarely so late with my courses, and I have begun to feel sick these last few days. But it may be nothing.’ She will say no more.

Henry’s heart is racing inside his chest with familiar apprehension and hope. ‘A child!’ he whispers to Blackie, who thumps the stub of her tail once on the flagstones. This time it will surely be different. His new wife’s first baby.

Henry pays slightly less attention to the rest of the day than he should. Ignoring his father’s reticence, he goes with him anyway to examine his windmill up in Cowleaze field though the tenant is out, then they skirt across to Inmead. Though they stand and look out at the view to the wet moorfields, they do not speak, and as his father does not ask about the trees he does not tour the orchards with him as Henry had planned. Indeed they do not do anything he planned; he feels rather superfluous, as though he were following his father about in the same, slavish manner as Blackie, trotting at his heels. His mind is elsewhere now, though, and he is almost grateful when the horses are got ready early and his father and stepmother leave despite the special supper being prepared.

The very house itself seems to let out a sigh of relief to see Joan Young gone, as the carriage containing her pulls mercifully out of the yard and onto the track towards the road, trundling back off to Sherborne again where she belongs. His father had not mentioned, Henry realizes, any sale of cows.

He goes straight to the parlour to find Frances, to examine her closely for clues.

‘Well,’ he says. ‘That was not a complete disaster, was it.’

‘Is there no stone which that woman will leave unturned?’ she exclaims, quite amazed at Joan Young’s rudeness even though she had been warned.

‘Probably not. But she is your mother-in-law, and there is nothing to be done about it,’ Henry says.

‘Why is she like that?’

‘Because she had seen herself here, upon marriage to my father. Here at Lytes Cary. She believed that she would be first lady of this manor, did not anticipate that he would stand aside and allow me to manage the land, while he retired with his new wife to an unimposing though pleasant enough house in Sherborne. By virtue of my being the sole heir to my father’s estate as eldest son, I have ruined her plans – and she is always reminded of this on coming here.’

Chapter VIII.

Of CINQUEFOYLE, or Five finger grasse. The great yellow cinquefoil hath round tender stalks, running abroad. The roote boyled in vineger, doth mollifie and appease fretting and consuming sores.

IT IS THE TWELFTH OF MARCH, and the second week of Lent. Outside in the last of a spring frost the plants are made of glass, the sun full upon them, a few melted drops catching light and winking colours. Henry walks the edge of the estate, steam rising from the river like a pan seething. The wood is a theatre, cutout black twigs shot through with vapour and diffuse beams of light against which birds flit, softly translucent. The willow’s tawniness is flaring to orange with the year’s growth, a supple bristle of shoots. Coming back through the garden Henry watches honey bees among the snowdrops, their legs fat with yellow catkin pollen. He remembers to avoid the upper garden door, so that he does not have to speak to Widow Hodges.

Today Henry takes delivery of seeds.

Looking through them when the man has gone, he has to admit that he’s probably bought too much. There are others on order, too, but the seedsman doesn’t pass through very often and Henry was keen not to overlook a chance to buy many sorts. The man had parsley and radish which he said had come from nearby, and endive, cucumber, anise, lettuce, purslane and pompion from further afield, mostly London. Henry also took pear kernels brought from Worcestershire, and he was tempted into buying fourteen liquorice plants, even though he suspects they will not do well on this kind of soil.

It is like a banquet, a seed banquet at his desk as he sits there opening the little packets one by one and relishing their differences: pale seeds of angelica like discarded shells of dull, brown beetles – flat and ribbed as if each one had been squashed in the overcrowded seedhead. He puts one into his mouth for that explosion of resinous savour, harsh at first then with a distinctive soapy undertow. Astonishing, he thinks, going on chewing, his tongue tingling and numb, how such insignificant, woody flecks can unleash such potency. He has seeds of ammi, too. Horribly dry and bitter. Smallage lives up to its name; the seeds are minute, scarcely bigger than grains of sand or mites. Alexander seed is black and large, like fat rat’s droppings. Gromwell is of a cold dense grey like that of tin-glaze china, quite startlingly like the eyes of cooked fish – with a high shine on each, and a faint patch of yellow blush. Not perfectly round, these seeds are mobile, free-flowing on his hand.

He also has dill, vervain, motherwort, thlaspi of Candy, sanicle, dittany, thyme, aristolochia, pennyroyal, calamint, centuary, alecost, herb of Grace, and wafer-thin moons of lunary; some call it Honesty but what is truth or honesty or lies to a plant? Such riches at his fingertips!

Of course for years he has bought in seeds for the vegetable yard, but this year his enthusiasm bubbles over even for them, as well as the seeds for the Knot, as though he is seeing them anew. He already has plenty of onion seed bought locally in March – maybe three pounds in weight. He digs his hand in and lets the seeds run through them in his delight as he opens each little sack and examines the contents, sniffs them, cracks a few open with his teeth. There are various peas, and borlotti beans in their stiffly undulating parchment pods.

He pours a mixture of some of the peas and beans into a pot to gloat over at his desk. They are soft red and brown and green, silkily dry, wrinkled. They are the colour of dried blood, tallow, bone, fresh larder mould, lichen. They are as hard as shingle, as light as buttons. And they are all – he feels quite overwhelmed with the sheer mass of them – waiting. He puts his forefinger to them and stirs them about. He rattles a handful from palm to palm. They are extraordinary – how has he never heeded it so well? And the promise they contain. These things seem dead, and yet … A few drops of water, the enclosing dark earth with its minerals, the warmth of sunlight; and each of these desiccated, mummified little bits of toughness will hydrate, fatten and burst into vivid miraculous sweet shoots, climbing, sinewing towards the light.

Tobias Mote looks at them doubtfully, when Henry takes a fair selection out to show him.

‘That’s a fearful lot to be grown from seed,’ he says, scratching through his rat-coloured, curly hair. ‘We’d be better off buying in little plants already set from Mistress Shaw in Wells. Only so much time on a man’s hands. Can’t produce a nursery out of thin air in a year’s stretch.’ He points with a blunt, grimy forefinger at the dug turf around them. ‘Not with all this going on.’

Henry’s good mood is unshakeable. ‘But they’ll last, even if we can’t get round to sowing everything this season.’

‘If they don’t get mildewed, or eaten by mice, or stolen; or so long as they don’t sprout untowardly.’ Tobias Mote chuckles with more glee than Henry wants to hear. ‘There’s a lot can go wrong with seeds stored badly.’

Henry stops listening to him.

For a second he thinks he hears something else behind the garden wall, strains his ears, his heart beating, but it is the low noise of ravens up in the woods that sounds like men talking.

‘Anyway, I’ve been thinking, we’ll be needing a bank,’ Mote is saying. ‘We can cast up one here where it should catch the sun alright.’

‘And grow a soft kind of cover over it – then I must add grass seed to the list.’ Henry is making notes on a board propped on an overturned cask.

‘And grass it.’ Mote repeats. Henry finds this is an annoying habit he has, of saying again what has already been said; not as if he is committing it to memory, more as if he is weighing up the readiness of what has been decided upon, as one might judge a fruit in the palm of the hand during the course of a tour of the orchard. It is not that Tobias Mote is rude or disrespectful, just that he seems disconcertingly his own man, that won’t be bidden.

‘So that it can be used as a seat for contemplation amongst the calm of the plants, facing the Knot itself.’ Henry goes on regardless, still pleased with the idea. ‘I imagine in June it will be popular.’

‘Folk can sit and kick their heels, when they’ve little to do.’

Henry Lyte looks sharply at Mote, but he can’t see any evidence of sarcasm. Mote’s countenance is fixed always either to the far distance of the horizon, detecting the weather, or straight down to the soil to the matters in hand. He digs very fast and straight, as though he were racing. Only for trees, it seems, does he make an exception and look out to the middle ground. Once Henry saw him watching a fox crossing Easter Field with a hen from the yard in its jaws, a ruddy streak trotting diagonally, its brush out straight and triumphant.

‘See that devil go,’ he’d muttered grudgingly to no-one in particular.

But on the whole, Tobias Mote seems to know what is going on around him without looking, without ceasing his thin, see-sawing whistle, without raising his eyes from the ground as he digs or rakes. His ears are small and pricked, perhaps their bristle of hairs makes his hearing more acute than other men’s. Mary calls him the troll, because she is afraid of him. If she is naughty, he only has to mention his name to make her squeal and comply with parental requests.

‘Does he do magic?’ she’d whispered once in awe, when they were discussing the crop of skirrets laid like dead man’s fingers buttered on the plate at supper, but her stepmother dislikes that kind of talk and made her get down from the table. Frances applies herself with scant duty to prayer and worship at the appropriate moments of the day but has a horror of talk of spirits and the afterlife, that makes Henry suspect that her beliefs run wilder than some. Of course he can’t be sure of this as they have never discussed it, not being something a civilized family should concern itself with. His first wife Anys, he can’t help remembering, was devoted to prayer.

‘And on the shady slope behind the bank, for who ever thinks about what is behind them, we can set primroses, or violets as a surprise, and other little shy flowers that do not mind a lack of sunshine – all in due course,’ Henry adds hastily. He is determined to remain enthusiastic about remembering details, even in the face of cynicism. He paces up and down the length of land, which Mote is now raking finely, slighting the soil in preparation for the sowing as soon as the weather seems suitable.

Henry has hired a weeding woman who lives at Tuck’s, called Susan Gander. She has been pulling out neat, tender bits of dandelion, jack-by-the-hedge and long, easy roots of withywind, so that the beds are smooth and clear, and everything is ready for committing the seeds to the earth. Some areas are sown, and some left bare for pricklings to be set out later. Susan Gander is an odd woman, Henry decides. He has caught her staring at him when his back is turned, and when he speaks to her to give instruction, she doesn’t say much in return, just nods, staring all the time even as she tosses weeds into the basket, so that she sometimes misses. He knows she’s not a half-wit, she is the wife of John Gander who is the most reliable carter round here. He thinks perhaps she may be put out because at first he found it hard to remember her name, but now he has it, and still she goes on, which is making him feel almost paranoid. It happened when he saw her at church on Sunday, he swears he saw her surreptitiously turning round and watching him out of the corner of her eye, nudging her neighbour. Her behaviour proves to him something unpleasant he has been suspecting for a few weeks now.

There can be no longer any doubt that something has begun to quietly, insidiously, circulate the district about the nature of his first wife’s death. No-one has mentioned it to him, not a single mortal soul, but he hears the whispering and sees the glances, and slowly the whole ghastly mess is rearing its head again in an unformed, pliable version of itself like a bad dream.

He goes inside, and watches the sowing of seeds from the study for a while, with more than a touch of jealousy. Mote somehow knows he’s watching, brazenly raises his hand once to him. See? Henry mutters to himself, even his own gardener prefers him not to dig in the garden. He seems to regard it mostly as his own domain. But he does trust Mote sufficiently to carry out what they have agreed. The progress is invisible from here.

Henry prays, then goes to his manuscript, though it is hard to put his mind to it. Every day as the season draws on he finds it more of an effort to apply himself to its difficulty, tinkers with what little there is of it so far. He feels mired and tense.

The next day is grey, and the lesser celandines have kept their petals half-shut. A small brown hawk with pointed wings, not from round here, has been flying between the pear trees and making the blackbirds jittery. By midday the pale sky has lowered and dissolved into a mizzling fine drift of rain that is perfect for moistening, nurturing those seeds laid already in the earth. Tobias Mote says that a successful life for any seed is determined in the first day – the first hours, even – of being planted.

Watching the hawk whirr up to the edge of the copse, Henry is reminded of a reddish-brown moth and thinks it softly beautiful, until he sees its decisive landing in the ash tree, cruel feet outstretched and latching onto the bough so swiftly that he flinches. It is a meat-eater, through and through.

Chapter IX.

Of PLANTAINE, or Waybrede. The third kind of plantaine is smaller than the second, the leaves bee long and narrow, with ribs of a darke greene with smal poynts or purples. The roote is short and verie full of threddie strings.

FRANCES QUICKENED TODAY. Henry can’t feel it of course, though he puts his hand dutifully on her belly, but he praised God for it; another healthy child kicking in the womb. He can never picture a miniature human in there, like those shown in the diagrams in medical books. His mind’s eye suggests rather that it is a pinkish kind of grub or caterpillar, that will later transform into something more recognizable, when it is pressing tiny feet and hands against the inner side of her belly skin. He is after all an experienced father. There were the births of Edith, Mary, Jane and Florence, and there was the other birth too, but this is too painful for him to remember. This last memory is the one that is slippery, evasive, so deeply interred that he can’t even acknowledge it. He is adept at forgetting; extremely adept.

‘Come and see the garden today, Frances!’ he says, on impulse.

‘Then you must wait while I find my old shoes,’ she says.